Published online Mar 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i12.3706

Peer-review started: September 4, 2014

First decision: October 14, 2014

Revised: October 31, 2014

Accepted: December 1, 2014

Article in press: December 1, 2014

Published online: March 28, 2015

Processing time: 207 Days and 16.3 Hours

AIM: To assess the prognostic value of c-Met status in colorectal cancer.

METHODS: We conducted a search in PubMed, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library covering all published papers up to July 2014. Only studies assessing survival in colorectal cancer by c-Met status were included. This meta-analysis was performed by using STATA11.0.

RESULTS: Ultimately, 11 studies were included in this analysis. Meta-analysis of the hazard ratios (HR) indicated that patients with high c-Met expression have a significantly poorer overall survival (OR) (HR = 1.33, 95%CI: 1.06-1.59) and progression-free survival (PFS) (HR = 1.47, 95%CI: 1.03-1.91). Subgroup analysis showed a significant association between high c-Met expression and poorer overall survival in the hazard ratio reported (HR = 1.41, 95%CI: 1.08-1.74).

CONCLUSION: The present meta-analysis indicated that high c-Met expression was associated with poor prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer.

Core tip: High c-Met expression was found in colorectal cancer and showed a positive relationship with early tumor invasion and metastasis. However, there still seems to be no consensus about the prognostic properties of c-Met status. In this paper, after combing the data from 11 retrospective studies with 1,895 patients, the authors found that high c-Met expression was associated with poor prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer.

- Citation: Liu Y, Yu XF, Zou J, Luo ZH. Prognostic value of c-Met in colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(12): 3706-3710

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i12/3706.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i12.3706

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common types of cancer worldwide. The 5-year survival rate of CRC is higher in the early stage due to radical surgical resection. However, many patients who underwent resection for primary colorectal cancer developed local recurrences or distant metastases, and had a shorter survival[1]. Recent treatment options for patients with advanced colorectal cancer included combining anti- epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or anti-vascular endothelial growth factor monoclonal antibodies with chemotherapy. Although many predictive markers have been identified[2-4], most of them are not commonly used in clinical practice. Identification of factors that can predict a more accurate prognosis is therefore required.

C-Met is a receptor tyrosine kinase encoded by the c-Met oncogene. High expression of c-Met has been found in different solid tumors and has a correlation with poor prognosis. In CRC, c-Met is considered to be related to tumor aggressiveness and invasiveness, as well as metastatic potential and poor prognosis[5-7]. In many tumors, the c-Met signaling pathway is activated aberrantly and represents one of the most important mechanisms of progression and invasiveness[8].

However, despite a large number of studies having researched the relationship between c-Met and survival in colorectal cancer, there still seems to be no consensus about the prognostic properties of c-Met status. It is for this reason that we performed this systematic review.

We searched PubMed, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library with the following terms: (c-Met AND (colon or rectal or colorectal) AND (carcinoma or tumor or cancer) AND prognosis) from 1990 to July 2014. To expand our search, references of the retrieved articles were also screened for additional studies. The inclusion criteria for primary studies were as follows: (1) proven diagnosis of CRC in humans; (2) overall survival (OS) or progression-free survival (PFS) analyzed by c-Met level; and (3) c-Met evaluation using reverse transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) or immunohistochemistry (IHC). Data from abstracts, review articles, and letters were excluded.

Relevant data were extracted from eligible studies by two researchers independently. The following information was extracted from each study: (1) basic information such as first author’s name, country, and publication year of article; and (2) variables such as number of patients analyzed, disease stage, methods of c-Met analysis, and hazard ratio (HR) with 95%CI for progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). When HRs and confidence intervals were not reported directly, we estimated them from the number of patients in each group and Kaplan-Meier curves by using the published methodology[9].

We calculated HRs with their 95%CIs to evaluate the relationships between c-Met level and PFS or OS. Heterogeneity was defined as I2 > 50%. When heterogeneity was judged among primary studies, the random-effects model was used. Otherwise, the fixed-effects model was used. Publication bias was assessed using Egger’s test. All statistical analysis was carried out with STATA 11.0.

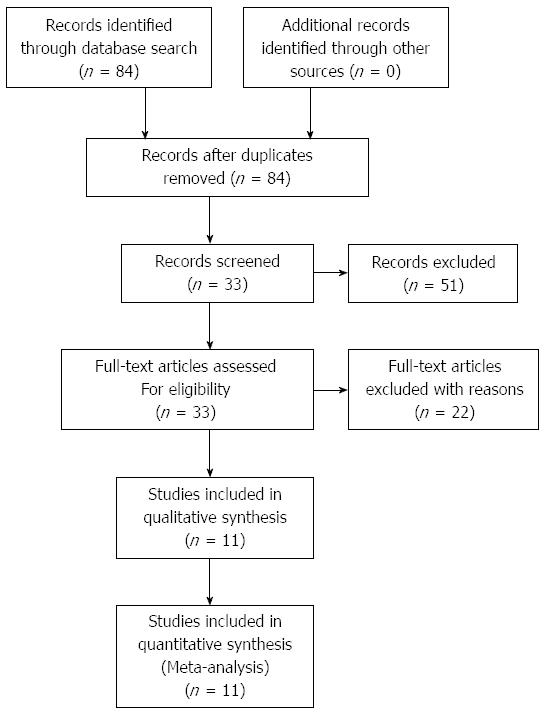

The initial search yielded 84 articles, of which 51 were excluded after screening of their titles and abstracts. Following the evaluation of the full text, a total of 11 studies were ultimately included in our study. The selection process for the studies involved in this meta-analysis is shown in Figure 1. From the 11 studies that were included[10-20], a total of 1,895 patients were analyzed. The characteristics of the involved studies are showed in Table 1.

| Ref. | No. of patients | Country | Method tostratify c-Metstatus | Stage | Stage(I, II) | High c-Metexpression | Survival | HR | 95%CI |

| Zeng et al[17], 2008 | 247 | United States | RT-qPCR | I-IV | 46% | 29% | OS | 2.081 | 0.94-4.62 |

| Voutsina et al[11], 2012 | 73 | Greece | IHC | IV | NS | 52% | OS | 4.59 | 2.05-10.28 |

| Resnick et al[19], 2004 | 134 | Israel | IHC | I-IV | NS | 77% | PFS | 0.811 | 0.24-3.75 |

| Garouniati et al[12], 2012 | 183 | Greece | IHC | I-IV | 61% | 72% | OS | 1.021 | 0.52-1.99 |

| Inno et al[13], 2011 | 73 | Italy | IHC | IV | NS | 75% | PFS/OS | 2.17/1.92 | 0.99-4.76/0.81-4.54 |

| De Oliveira et al[14], 2009 | 286 | Brazil | IHC | I-IV | 53% | 79% | PFS/OS | 1.651/1.211 | 0.56-4.21/0.85-2.06 |

| Kishiki et al[10], 2014 | 75 | Japan | IHC | I-IV | NS | 48% | PFS/OS | 1.46/1.16 | 1.06-2.02/0.73-1.82 |

| Ginty et al[16], 2008 | 583 | United States | IHC | I-IV | 46% | 62% | OS | 1.45 | 1.06-1.96 |

| Kammula et al[18], 2006 | 63 | United States | RT-qPCR | I-IV | 39% | 81% | OS | 2.44 | 1.05-5.68 |

| Lee et al[15], 2007 | 135 | Taiwan | IHC | I-IV | NS | 72% | PFS/OS | 10.05/3.93 | 2.54-43.84/1.40-10.99 |

| Umeki et al[20], 1999 | 43 | Japan | IHC/RT-qPCR | I-IV | 35% | 30%/12% | OS | 1.141 | 0.78-3.45 |

All of these studies were retrospective research. Of the 11 studies, two[11,13] included only patients with advanced disease (stage IV), while the remaining 9 studies[10,12,14-20] included patients with stage I-IV. None of the patients received therapy before resection of the primary tumor. C-Met evaluation was performed by IHC or PCR. The rate of high c-Met level ranged from 12% to 81% (median, 61%). The median follow-up time was 80 months (range from 25 to 140 mo). In most of these studies, c-Met expression level was evaluated by cell percentage. High c-Met expression was defined as >50% positive cells. OS was presented in 10 studies, and PFS was reported in five studies. Six studies[10,12,13,15,16,18] presented data on HR, with 95% CI for PFS or OS directly. The remaining five studies did not present HRs and 95%CIs directly, so we estimated them from Kaplan-Meier curves.

Forest plots for the relationships between c-Met level and overall survival are showed in Figure 2, with the results indicating a significant relationship between high c-Met expression and poorer OS (overall HR = 1.33, 95%CI: 1.06-1.59). No significant heterogeneity was found (P = 0.635, I2 = 0.0%) and the HR for OS was assessed by using the fixed-effects model. There was no significant publication bias in this analysis of OS (Begg’s test, P = 0.052; Egger’s test, P = 0.094).

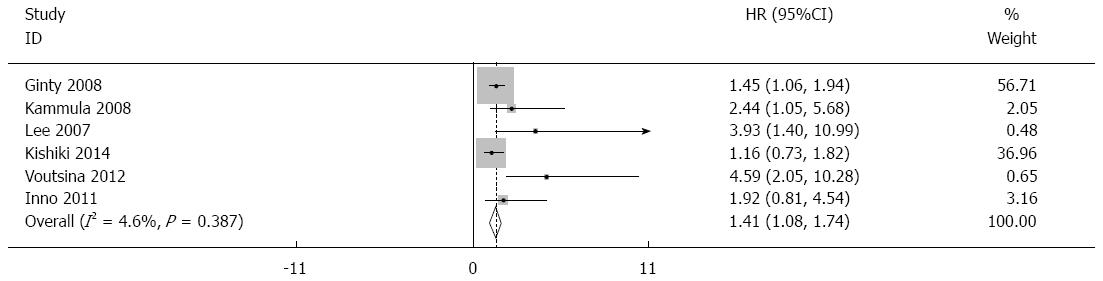

We also performed subgroup analysis in studies by HR reported. We found significant association between high c-Met expression and poorer overall survival in the hazard ratio reported (HR = 1.41, 95%CI: 1.08-1.74).

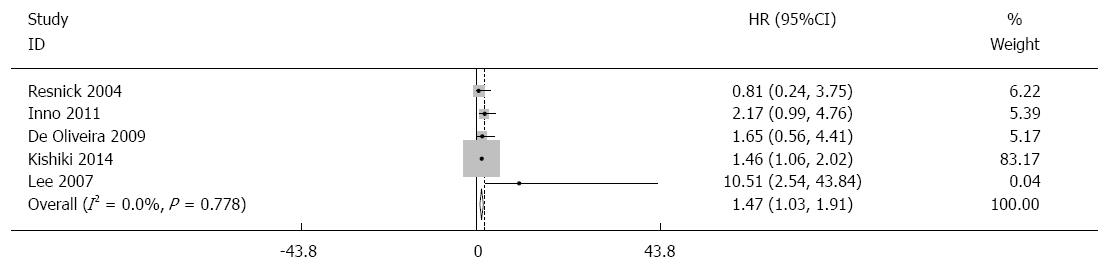

The pooled HR for PFS showed that patients with a high c-Met level had a significantly poorer PFS (HR = 1.47; 95%CI: 1.03-1.91). No significant heterogeneity was found (P = 0.778, I2 = 0.0%), and the pooled HR for PFS was assessed by using the fixed-effects model (Figures 3 and 4). There was no significant publication bias in this analysis of PFS (Begg’s test, P = 0.462; Egger’s test, P = 0.548).

The main cause of CRC-related death is metastases. Identification of patients who are at risk of developing distant metastases is important to cancer treatment and prognosis. c-Met overexpression or genetic alteration has been proven to play an important role in the pathogenesis of many tumor types. In CRC, overexpression of c-Met has been found to be associated with tumor progression.

This systematic review is based on 11 studies and includes 1,895 patients with CRC. The results of this meta-analysis showed the prognostic value of c-Met expression level in CRC patients. High c-Met expression significantly predicted poor OS and PFS. We also performed subgroup analysis in studies by HR reported. There was a significant relationship between high c-Met expression and poorer overall survival in the hazard ratio reported.

A study conducted by Kishiki et al[10] showed that c-Met overexpression was associated with shorter PFS in metastasis colorectal cancer (mCRC) patients with wild-type KRAS. All patients received cetuximab- or panitumumab-based therapy. However, the study was conducted retrospectively in a relatively small and heterogeneous population. 90% of the patients were treated with two or more chemotherapy regimens before they were given anti-EGFR treatment. In addition, the anti-EGFR treatment protocols were also heterogeneous. Therefore their findings needed to be validated by more prospective studies. Zeng et al[17] found that amplification of c-Met gene is a relatively rare event (3.6%) in CRC, and that the majority of amplified cases occurred in patients with synchronous hepatic metastases (stage IV).

After identification of c-Met involvement in cancer progression and metastasis, many in vitro experimental studies have showed that c-Met plays a role in resistance to anti-EGFR therapy. Inno et al[13] retrospectively evaluated a cohort of 73 patients with mCRC treated with a cetuximab-containing regimen. They found an association of high c-Met level with shorter PFS and OS in patients with mCRC, and that the c-Met pathway may be involved in primary resistance to cetuximab. However, their study cannot ascertain whether c-Met is a predictive biomarker, because they assessed only patients treated with a cetuximab-containing regimen. In CRC, many studies have proved that KRAS mutations predict unresponsiveness to EGFR-targeted monoclonal antibody therapies; however, there still about 26% of patients who are not responsive to EGFR-targeted therapy that are a wild-type for KRAS. Therefore, we hypothesize resistance to EGFR-targeted therapies may be mediated by the activation of parallel pathways such as the c-Met signaling pathway. Therefore more prospective studies are needed to affirm the results.

c-Met as a biomarker might be used to select advanced colorectal cancer patients who could benefit from targeted therapies. A growing number of studies from in vitro, in vivo, and in various stages of clinical testing have shown that c-Met tyrosine kinase (TK) inhibitors can block c-Met signaling and arrest or reverse tumor growth in a subset of human cancers[21,22]. Recently a few studies have shown that c-Met amplification confers high sensitivity to a specific c-Met TK inhibitor in lung cancer and gastric cancer[23,24]. All of these findings indicate that amplified c-Met may serve as a biomarker for targeted therapy.

Some limitations to this meta-analysis require particular note: heterogeneity; differences in clinical treatment; and different criteria to stratify c-Met status.

In conclusion, our meta-analysis demonstrated a significant association between high c-Met expression and poor OS and PFS in CRC for the first time. However, further larger prospective studies are needed to confirm these results.

High c-Met expression was found in colorectal cancer and showed a positive relationship with early tumor invasion and metastasis.

There still seems to be no consensus about the prognostic properties of c-Met status.

This is the first known paper to conduct a comprehensive meta-analysis with the aim of investigating the relationship between c-Met and prognosis of colorectal cancer. The authors found that high c-Met expression was associated with poor prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer.

This study furthers the understanding of the association of c-Met with colorectal cancer prognosis.

This is a well-performed meta-analysis that aims to assess the prognostic value of c-Met status in colorectal cancer. Its findings are interesting.

| 1. | Feezor RJ, Copeland EM, Hochwald SN. Significance of micrometastases in colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:944-953. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Itzkowitz SH, Bloom EJ, Kokal WA, Modin G, Hakomori S, Kim YS. Sialosyl-Tn. A novel mucin antigen associated with prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. Cancer. 1990;66:1960-1966. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Miyahara M, Saito T, Kaketani K, Sato K, Kuwahara A, Shimoda K, Kobayashi M. Clinical significance of ras p21 overexpression for patients with an advanced colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:1097-1102. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Leahy DT, Mulcahy HE, O’Donoghue DP, Parfrey NA. bcl-2 protein expression is associated with better prognosis in colorectal cancer. Histopathology. 1999;35:360-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zeng Z, Weiser MR, D’Alessio M, Grace A, Shia J, Paty PB. Immunoblot analysis of c-Met expression in human colorectal cancer: overexpression is associated with advanced stage cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2004;21:409-417. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Fujita S, Sugano K. Expression of c-met proto-oncogene in primary colorectal cancer and liver metastases. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1997;27:378-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shoji H, Yamada Y, Taniguchi H, Nagashima K, Okita N, Takashima A, Honma Y, Iwasa S, Kato K, Hamaguchi T. Clinical impact of c-MET expression and genetic mutational status in colorectal cancer patients after liver resection. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:1002-1007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yi S, Tsao MS. Activation of hepatocyte growth factor-met autocrine loop enhances tumorigenicity in a human lung adenocarcinoma cell line. Neoplasia. 2000;2:226-234. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med. 1998;17:2815-2834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kishiki T, Ohnishi H, Masaki T, Ohtsuka K, Ohkura Y, Furuse J, Watanabe T, Sugiyama M. Overexpression of MET is a new predictive marker for anti-EGFR therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer with wild-type KRAS. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;73:749-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Voutsina A, Tzardi M, Kalikaki A, Zafeiriou Z, Papadimitraki E, Papadakis M, Mavroudis D, Georgoulias V. Combined analysis of KRAS and PIK3CA mutations, MET and PTEN expression in primary tumors and corresponding metastases in colorectal cancer. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:302-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Garouniatis A, Zizi-Sermpetzoglou A, Rizos S, Kostakis A, Nikiteas N, Papavassiliou AG. FAK, CD44v6, c-Met and EGFR in colorectal cancer parameters: tumour progression, metastasis, patient survival and receptor crosstalk. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:9-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Inno A, Di Salvatore M, Cenci T, Martini M, Orlandi A, Strippoli A, Ferrara AM, Bagalà C, Cassano A, Larocca LM. Is there a role for IGF1R and c-MET pathways in resistance to cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer? Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2011;10:325-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | De Oliveira AT, Matos D, Logullo AF, DA Silva SR, Neto RA, Filho AL, Saad SS. MET Is highly expressed in advanced stages of colorectal cancer and indicates worse prognosis and mortality. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:4807-4811. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Lee CT, Chow NH, Su PF, Lin SC, Lin PC, Lee JC. The prognostic significance of RON and MET receptor coexpression in patients with colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1268-1274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ginty F, Adak S, Can A, Gerdes M, Larsen M, Cline H, Filkins R, Pang Z, Li Q, Montalto MC. The relative distribution of membranous and cytoplasmic met is a prognostic indicator in stage I and II colon cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3814-3822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zeng ZS, Weiser MR, Kuntz E, Chen CT, Khan SA, Forslund A, Nash GM, Gimbel M, Yamaguchi Y, Culliford AT. c-Met gene amplification is associated with advanced stage colorectal cancer and liver metastases. Cancer Lett. 2008;265:258-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kammula US, Kuntz EJ, Francone TD, Zeng Z, Shia J, Landmann RG, Paty PB, Weiser MR. Molecular co-expression of the c-Met oncogene and hepatocyte growth factor in primary colon cancer predicts tumor stage and clinical outcome. Cancer Lett. 2007;248:219-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Resnick MB, Routhier J, Konkin T, Sabo E, Pricolo VE. Epidermal growth factor receptor, c-MET, beta-catenin, and p53 expression as prognostic indicators in stage II colon cancer: a tissue microarray study. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3069-3075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Umeki K, Shiota G, Kawasaki H. Clinical significance of c-met oncogene alterations in human colorectal cancer. Oncology. 1999;56:314-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kong-Beltran M, Stamos J, Wickramasinghe D. The Sema domain of Met is necessary for receptor dimerization and activation. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:75-84. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Kim SJ, Johnson M, Koterba K, Herynk MH, Uehara H, Gallick GE. Reduced c-Met expression by an adenovirus expressing a c-Met ribozyme inhibits tumorigenic growth and lymph node metastases of PC3-LN4 prostate tumor cells in an orthotopic nude mouse model. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:5161-5170. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Smolen GA, Sordella R, Muir B, Mohapatra G, Barmettler A, Archibald H, Kim WJ, Okimoto RA, Bell DW, Sgroi DC. Amplification of MET may identify a subset of cancers with extreme sensitivity to the selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor PHA-665752. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2316-2321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 416] [Cited by in RCA: 429] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mazzone M, Comoglio PM. The Met pathway: master switch and drug target in cancer progression. FASEB J. 2006;20:1611-1621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Falletto E, Hoensch HP, Tanyi M S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Rutherford A E- Editor: Wang CH