Published online Mar 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i12.3547

Peer-review started: October 29, 2014

First decision: November 26, 2014

Revised: December 17, 2014

Accepted: January 30, 2015

Article in press: January 30, 2015

Published online: March 28, 2015

Processing time: 152 Days and 1.4 Hours

AIM: To determine the clinicopathologic characteristics of surgically treated ulcerative colitis (UC) patients, and to compare the characteristics of UC patients with colitis-associated cancer (CAC) to those without CAC.

METHODS: Clinical data on UC patients who underwent abdominal surgery from 1980 to 2013 were collected from 11 medical institutions. Data were analyzed to compare the clinical features of patients with CAC and those of patients without CAC.

RESULTS: Among 415 UC patients, 383 (92.2%) underwent total proctocolectomy, and of these, 342 (89%) were subjected to ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. CAC was found in 47 patients (11.3%). Adenocarcinoma was found in 45 patients, and the others had either neuroendocrine carcinoma or lymphoma. Comparing the UC patients with and without CAC, the UC patients with CAC were characteristically older at the time of diagnosis, had longer disease duration, underwent frequent laparoscopic surgery, and were infrequently given preoperative steroid therapy (P < 0.001-0.035). During the 37 mo mean follow-up period, the 3-year overall survival rate was 82.2%.

CONCLUSION: Most Korean UC patients experience early disease exacerbation or complications. Approximately 10% of UC patients had CAC, and UC patients with CAC had a later diagnosis, a longer disease duration, and less steroid treatment than UC patients without CAC.

Core tip: This multi-center study is the first nationwide report on the surgical outcomes of Korean ulcerative colitis (UC) patients and reflects the recent status of surgically treated Korean UC patients. The authors found that most Korean UC patients experienced early disease exacerbation or complications. Approximately 10% of UC patients had colitis-associated cancer (CAC), and UC patients with CAC had a later diagnosis, a longer disease duration, and less steroid treatment than UC patients without CAC.

- Citation: Yoon YS, Cho YB, Park KJ, Baik SH, Yoon SN, Ryoo SB, Lee KY, Kim H, Lee RA, Group CSYIS, Coloproctology KSO. Surgical outcomes of Korean ulcerative colitis patients with and without colitis-associated cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(12): 3547-3553

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i12/3547.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i12.3547

Despite the growing use of medical salvage treatment, surgery, including total proctocolectomy (TPC), remains a cornerstone for managing ulcerative colitis (UC). Surgery should be regarded as a life-saving procedure for patients with acute severe colitis and must be seriously considered in any medically intractable patient or patient with colonic dysplasia or malignancy[1]. A recent study of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) showed excellent quality of life and a good functional outcome in UC patients treated with this modality[2]. Colitis-associated cancer (CAC) is a well-recognized complication of UC[3]. The overall prevalence of CAC in UC patients is 3.7%, and cases of CAC in UC patients account for only 1% of all colorectal cancer (CRC) cases observed in the Western population[3,4]. There is also a general consensus that patients with longstanding, extensive UC have an increased risk of developing CAC[3,5].

Although the prevalence of UC is lower in South Korea than in Western countries, the number of patients with UC as well as those with UC and CAC has increased steadily since 1980[6,7]. There are clear ethnic differences in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) between Asian and Western populations[8]. The present study is primarily intended to fulfill the current lack of information on the clinicopathologic characteristics of UC patients who undergo surgical treatment in South Korea. We also attempted to compare the clinical characteristics of surgically treated UC patients with and without CAC.

The data for biopsy-proven UC patients who underwent abdominal surgery from January 1980 to July 2013 were collected retrospectively. The surgeries were performed at 11 different medical institutions, i.e., ten university hospitals and one colorectal clinic. The data of 419 patients were initially collected, and four patients were excluded because they had not undergone surgery for UC. Thus, data from a total of 415 UC patients were analyzed to compare the clinical variables of UC patients with cancer to those of patients without cancer. The variables were gender, family history, age at diagnosis, symptom duration before diagnosis, preoperative medication, the indication for surgery, the presence of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), the extent of colonic involvement, the type of surgery, the postoperative complications, and mortality. In the patients with cancer, additional data were gathered, including preoperative identification of cancer or dysplasia, preoperative serum carcino-embryonic antigen (CEA) level, pathologic data, adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy, recurrence of cancer, and survival status at the time of the last follow-up. Histologically, tumors were classified as either low-grade (well-differentiated or moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma) or high-grade (poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma or mucinous or signet-ring cell carcinoma). An early complication was defined as one occurring within 90 d after the main surgical intervention. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of each medical institution. The mean follow-up was 68.4 mo (range: 0-286 mo).

A cross-table analysis using Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, was used to compare the discrete variables of patients with cancer to those of patients without cancer. The Student’s t-test was used for between-group comparisons of continuous variables. Among UC patients with cancer, recurrence and overall survival were used to evaluate the clinical outcome. Survival outcomes were compared using the Kaplan-Meier method with a log-rank test. All reported P values are two-sided, and the P < 0.05 values were considered to indicate statistical significance. SPSS software version 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States) was used for statistical analysis.

Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of 415 UC patients who underwent surgical treatment. The mean preoperative medication period was 41.9 mo. Most of the patients (n = 368, 88.7%) were treated with 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA). Steroids were administered to 315 patients (75.9%) as a first-line treatment for acute severe colitis before colectomy. In patients who failed to respond to steroids, infliximab (n = 33), cyclosporine (n = 26), and 6-mercaptopurine (n = 7) were used as second-line treatments. The most common reason for performing surgery was medical intractability, followed by dysplasia or malignancy, and bleeding (Table 2). With regard to surgical treatment, 383 patients (92.2%) underwent TPC, of which 342 patients (89%, Table 3) underwent IPAA. Among the 342 patients who underwent IPAA, 53 mucosectomies with hand-sewn IPAA (15.4%) were performed. Mucosectomy was more frequently performed in patients with cancer (27.2%) than in those without cancer (14.7%), although the difference was not significant. Laparoscopic-assisted procedures were performed in 46 patients (11.1%). Complications occurred in 144 patients (34.7%), 79 of whom had early complications and 65 of whom had late complications. The most common early complication was ileus (n = 21), followed by bleeding (n = 16), anastomotic leakage (n = 15), intra-abdominal abscess (n = 8), and major wound dehiscence (n = 6). Late complications were pouchitis (n = 48), fistula (n = 9), and anastomotic stricture (n = 6). Preoperative steroid therapy was more frequently used in open surgery than in laparoscopic surgery (79% vs 50%, P < 0.001). The complication rate in patients undergoing preoperative steroid therapy was higher than that in patients who did not undergo preoperative steroid therapy (38% vs 26%, P = 0.04). There was no significant difference in the complication rates between open and laparoscopic surgery.

| Variable | Total (n = 415) | UC w/o cancer (n = 368) | UC w/ cancer (n = 47) | P value |

| Gender, male | 212 (51.1) | 186 (50.5) | 26 (55.3) | 0.642 |

| Age at diagnosis (yr) | 38.4 ± 0.7 | 37.9 ± 0.7 | 42.7 ± 2.6 | 0.035 |

| Age at surgery (yr) | 43.4 ± 0.7 | 42.2 ± 0.8 | 52.9 ± 2.1 | < 0.001 |

| Period between diagnosis and surgery (yr) | 5.0 ± 0.3 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 10.2 ± 1.3 | < 0.001 |

| Symptomatic period (yr) | 6.0 ± 0.3 | 5.3 ± 0.3 | 11.9 ± 1.2 | < 0.001 |

| Family history | 5 (1.4) | 3 (0.9) | 2 (4.8) | 0.103 |

| Extracolic manifestation | 49 (11.8) | 45 (12.2) | 4 (8.5) | 0.632 |

| PSC | 5 (1.2) | 4 (1.1) | 1 (2.1) | 0.453 |

| Preoperative steroid therapy | 315 (75.9) | 297 (80.7) | 18 (38.3) | < 0.001 |

| Location, pancolitis | 320 (77.1) | 284 (77.2) | 36 (76.6) | 0.025 |

| Left side colitis | 88 (21.2) | 80 (21.7) | 8 (17.0) | |

| Proctitis only | 7 (1.7) | 4 (1.1) | 3 (6.4) | |

| Laparoscopic surgery | 46 (11.1) | 34 (9.2) | 12 (25.5) | 0.002 |

| Overall complications | 144 (34.7) | 133 (36.1) | 11 (23.4) | 0.103 |

| Early | 79 (19.0) | 75 (20.4) | 4 (8.5) | 0.050 |

| Late | 65 (15.7) | 58 (15.8) | 7 (14.9) | 0.878 |

| Mortality | 5 (1.2) | 5 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 0.925 |

| Variable | Value |

| Medical intractability | 270 (65.1) |

| Dysplasia or malignancy | 52 (12.5) |

| Bleeding | 31 (7.5) |

| Perforation | 19 (4.6) |

| Toxic megacolon | 18 (4.3) |

| Obstruction | 9 (2.2) |

| Fistula | 3 (0.7) |

| Others | 13 (3.1) |

| Total | 415 (100) |

| Variable | Value |

| Total proctocolectomy | 383 (92.2) |

| w/ IPAA | 342 (89) |

| One-stage procedure | 38 (9.2) |

| Two-stage procedure | 286 (68.9) |

| Three-stage procedure | 18 (4.3) |

| Mucosal proctectomy | 53 (12.8) |

| w/ end ileostomy | 41 (11) |

| Total colectomy w/ end ileostomy | 11 (2.7) |

| Other colon surgery | 21 (5.1) |

| Total | 415 (100) |

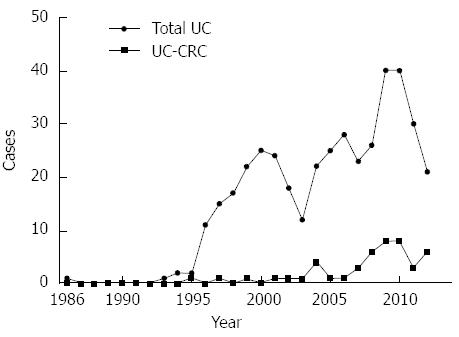

Forty-seven patients had colorectal malignancies (11.3%): 45 patients had adenocarcinomas, and the two had a neuroendocrine carcinoma and a lymphoma, respectively. There was a suspicion of malignancy before surgery in 44 patients (93.6%). Although there was no difference in the annual cumulative number of surgeries performed for UC, surgery for cancer with UC has been increasing recently (Figure 1). Compared with the UC patients without cancer, the UC patients with cancer were older at the time of diagnosis and surgery, and had longer disease duration, frequent laparoscopic surgery, infrequent preoperative steroid therapy, and a slightly lower rate of early postoperative complications (Table 1). Two patients were diagnosed with rectal adenocarcinomas 7 and 11 years after total colectomy with end ileostomy and underwent completion proctectomy. None of the patients had malignancy around the pouch or anal transitional zone (ATZ) after IPAA.

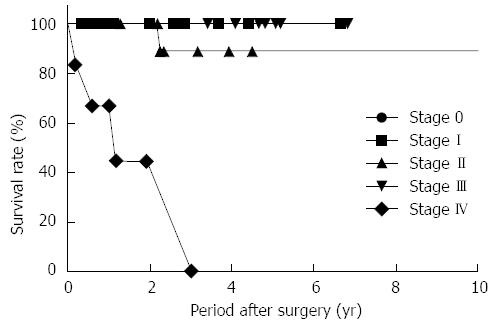

Table 4 summarizes the characteristics of the 45 UC patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma. Two patients with rectal cancer underwent preoperative chemoradiation therapy. Adjuvant chemotherapy was administered to 24 patients (53.3%) with advanced CAC. During the 37-mo mean follow-up period (range: 1-138 mo), the 3-year overall survival rate was 82.2%. The only patient with local recurrence had stage II CAC. She was diagnosed with recurrent pelvic lymph-node metastasis 1 year postoperatively and finally died due to cancer progression. Among the seven patients with stage IV CAC, five died, and two patients were alive although with disease, at the end of the study period. In patients with stage 0, I, and III CAC, no recurrences or deaths were observed (Figure 2).

| Variable | Value |

| Location | |

| Right colon | 10 (22.2) |

| Left colon | 18 (40.0) |

| Rectum | 17 (37.8) |

| CEA | |

| < 6 ng/mL | 33 (73.3) |

| ≥ 6 ng/mL | 6 (13.3) |

| Unknown | 6 (13.3) |

| Tumor size (cm), mean ± SE | 3.9 ± 0.4 |

| < 4 cm | 24 (53.3) |

| ≥ 4 cm | 15 (33.3) |

| Unknown | 6 (13.3) |

| Histology | |

| Well-differentiated | 10 (22.2) |

| Moderately differentiated | 26 (57.8) |

| Poorly differentiated | 4 (8.9) |

| Mucinous | 5 (11.1) |

| Stage | |

| 0 | 3 (6.7) |

| I | 13 (28.9) |

| II | 11 (24.4) |

| III | 11 (24.4) |

| IV | 7 (15.6) |

| Curability of the surgery | |

| R0 | 35 (77.8) |

| R1 | 3 (6.7) |

| R2 | 7 (15.5) |

| Total | 45 (100) |

This multi-center study is the first nationwide report on the surgical outcomes of Korean UC patients and reports the recent status of surgically treated Korean UC patients. As our study involved most high-volume, tertiary-care, medical institutions in South Korea, we calculated that the patient cohort (approximately n = 5800 patients) at 11 of these institutions corresponded to approximately 45% of all recorded Korean patients with UC. This was indirectly calculated by counting the number of follow-up UC patients at each institution and using the population data of a previous KASID study[4]. Recently, colorectal surgeons have reported encountering increasing numbers of UC patients with CAC in their clinical practice. Therefore, our study was designed primarily to determine the incidence and characteristics of Korean UC patients with CAC. Unexpectedly, the number of these patients was relatively small, and their follow-up periods were too short to analyze survival outcomes.

In the clinical course of UC, approximately 4% to 9% of UC patients will require colectomy within the first year of diagnosis, whereas the risk of requiring colectomy after the first year is 1% per year[9]. A European population-based study revealed a 7.5% colectomy rate during the 5-year follow-up period[10]. In our study, two-thirds of the UC patients underwent surgery due to exacerbation of their disease (severe colitis), and approximately 20% of the UC patients underwent surgery due to complicating disease including massive bleeding or perforation. These patients had an average 4.3-year interval between diagnosis and surgery. Conversely, only 10% of the UC patients who underwent surgery had CAC. These patients had different clinical characteristics, such as a later diagnosis, disease duration of more than 10 years, and a lower rate of preoperative steroid therapy than patients without CAC.

Needless to say, the standard-of-care surgery for UC is TPC with IPAA, which most of the patients in this study received. IPAA is a curative and well-tolerated procedure, although it is technically demanding and has a high morbidity rate. A recent study of IPAA demonstrated early complications in 33%, and late complications in 29% of patients, thus resulting in an overall pouch excision rate of 5%[2]. Our study showed slightly lower complication rates than those seen in Fazio’s study. However, this is not surprising, considering that their database was prospectively well-maintained at a single medical institution and that our databases were collected at 11 medical institutions over a short period of time. IPAA can be performed in one, two, or three stages. In our study, 84% of the IPAAs were performed using a two-stage procedure, which gave similar results to those reported in a recent, large-scale cohort study[2]. In patients undergoing a three-stage procedure, completion proctectomy or rectal surveillance is very important. A recent study reported that only 65% of patients completed IPAA after subtotal colectomy, 40% complied with rectal surveillance, and two patients developed rectal cancers, which is consistent with our study results[11].

The “double stapled” ileal J pouch-anal anastomosis is the most popular standard pouch-anal anastomosis method, while mucosectomy and hand-sewn anastomosis are reserved for patients with dysplasia or cancer[2,12]. However, whether mucosectomy protects against the development of ATZ and pouch cancer is unclear, and controversy exists over whether the beneficial effect of mucosectomy in preventing neoplasia is outweighed by its negative effect on ileal pouch function[13]. Although mucosectomy was frequently performed on our UC patients with cancer, it was difficult to verify the benefits of mucosectomy for preventing ATZ cancer due to the short follow-up period in our study. A recent review also showed that 32 UC patients had cancers in the ATZ; of these patients, 28 underwent mucosectomy. The study concluded that mucosectomy does not necessarily eliminate cancer risk in the ATZ[14].

Laparoscopic IPAA for UC is feasible; however, to date, the evidence in the literature is still inconclusive. Current data suggest that it allows a shorter hospital stay, a shorter ileus, faster recovery, and less postoperative pain, along with better cosmesis when minimally invasive surgery is employed. Significantly longer operative times are universally reported when laparoscopy is employed[15]. In our study, only 11% of the UC patients underwent laparoscopic-assisted surgery. Among these, the complication rates did not differ from those of open surgery and were closely correlated with the infrequent use of preoperative steroid therapy. Many studies suggested that patients who are taking high-dose steroids are at an increased risk of early complications after IPAA[16,17]. As cumulative evidence shows that laparoscopic surgery for CRC is not inferior to open surgery, with respect to patient survival and cancer recurrence rates[18], laparoscopic IPAA surgery might be feasible in selected UC patients with cancer.

Long disease duration, male sex, a young age at diagnosis of UC, extensive colitis, and PSC are well-known risk factors for developing CAC[5,14,19]. The disease duration is the most important factor for UC-associated CRC, of which the incidence rates correspond to cumulative probabilities of 2% by 10 years, 8% by 20 years, and 18% by 30 years[3]. As our study included UC patients who underwent surgery, it was difficult to determine the risk factors for UC-associated CRC. We also found that the duration of UC was longer in patients with CAC than in patients without CAC. A previous KASID study of UC-associated CRC in South Korea revealed that the overall prevalence of CRC was 0.37%, the mean age at diagnosis was 49.6 years, and the mean duration of UC was 11.5 years, all of which are consistent with our study results[4]. During the KASID study period of 1970 to 2005, Kim et al[4] found 26 UC patients with CAC. However, 80% of the UC patients with CAC in our study were identified after 2005 and had earlier disease stages than those in the KASID study. Although it was difficult to identify changes in the management and preventive strategies for CAC during the study period, our findings might be explained by the increase in the UC cohort, as well as by the recent increase in the use of surveillance colonoscopy for the prevention of CAC. In addition, a very low incidence of PSC was consistently found in both studies. By comparing our results with those of the previous KASID study, we also verified that the incidence of UC-associated CRC is rapidly increasing.

Compared with sporadic CRC, the carcinogenesis of UC-associated CRC is different, as it develops from dysplasia in a carcinogenic pathway known as the dysplasia-carcinoma sequence[14]. Interestingly, P53 mutations occur earlier in IBD-associated cancer than in sporadic CRC. APC mutations in IBD-associated cancer, a key initiating event, occur later than sporadic CRC[20]. Furthermore, microsatellite instability (MSI) is frequently observed in UC patients[21], although MSI in IBD shows infrequent MLH1 hyper-methylation, which is a dominant feature of sporadic CRC[22]. These molecular genetic differences between IBD-associated cancer and sporadic CRC might be responsible for their different clinicopathologic features. The pathologic features of UC-associated CRC frequently present as a mucinous or signet-ring-cell histology compared with the features of sporadic CRC (17%-21%)[23,24], which is consistent with our results (20%). A previous Japanese study indicated that a frequent mucinous or a signet-ring-cell histology in UC-associated cancer contributed to the poorer prognosis of UC-associated cancer compared with that of sporadic CRC[23].

Whether the survival rate of UC-associated CRC is poorer than that of sporadic CRC is controversial. Earlier studies showed similar survival rates for UC-associated CRC and sporadic CRC[25,26]. However, recent well-designed Danish and Japanese studies revealed slightly poorer survival rates for UC-associated CRC patients[23,27]. In Norwegian and Swedish population-based studies, the prognosis of IBD-associated CRC was poorer than that of sporadic CRC (a mortality rate ratio of 3.71 for Norwegians and an overall hazard ratio of 1.26 for Swedes)[28,29]. As all of these studies had the common limitation of a small patient cohort, it is difficult to obtain an accurate prognosis for UC-associated CRC patients. Although our study also had the same limitation of a small number of cases of UC-associated CRC as well as a short follow-up period, the survival of UC patients with CAC in our study was much better than that seen in recent studies. Except for stage IV patients, among 38 patients with stage 0 to III disease, only one with a recurrence died. Long-term follow-up and further patient enrollment might help provide an accurate prognosis for Korean UC patients with CAC in the future.

This study had some of the limitations of a retrospective study. There were differences in the reliabilities of the databases, which differed from institution to institution. Although a few institutions had prospectively well-maintained databases, others did not. As we previously mentioned, our study population was very limited as it only included patients who underwent surgery. Therefore, it is difficult to determine the risk factors for UC-associated CRC from this cohort.

In conclusion, Korean UC patients who underwent surgery had two distinct features. Most of the treated patients had early disease exacerbation or complications. Approximately 10% of the surgically treated UC patients had CAC and characteristics of late diagnosis, longer disease duration, and lower preoperative steroid treatment compared with those without CAC.

The authors thank Drs. Hye Jin Kim, Jae-Kyun Ju and Ki Yoon Lim for their assistance in the acquisition of data.

Despite the advancements in medical treatment, surgery remains a cornerstone for managing ulcerative colitis (UC). Surgery should be regarded as a life-saving procedure for patients with acute severe colitis and patients with colonic malignancy. Colorectal cancer is a well-recognized complication of long-term UC.

Although the prevalence of UC is low in Asian countries, the number of patients with UC as well as those with colorectal cancer has increased steadily since 1980. There are clear ethnic differences in inflammatory bowel disease between Asians and Westerners. The present study addressed the current lack of information concerning the surgical treatments and outcomes of UC patients by determining the clinicopathologic characteristics of Korean UC patients who underwent surgical treatment.

Only 10% of surgically treated UC patients had colitis-associated cancer. These patients were characteristically older at the time of diagnosis, had longer disease duration, underwent frequent laparoscopic surgery, and were infrequently given preoperative steroid therapy. Surgical outcomes of UC-associated cancer patients were similar to those of sporadic colorectal cancer patients.

Understanding the clinicopathologic characteristics of UC-associated colorectal cancer might help better manage UC patients and make optimal decisions about which type of surgery to apply.

This is an interesting multicenter study of the clinic-pathologic characteristics of patients with UC who underwent surgery.

| 1. | Dayan B, Turner D. Role of surgery in severe ulcerative colitis in the era of medical rescue therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3833-3838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fazio VW, Kiran RP, Remzi FH, Coffey JC, Heneghan HM, Kirat HT, Manilich E, Shen B, Martin ST. Ileal pouch anal anastomosis: analysis of outcome and quality of life in 3707 patients. Ann Surg. 2013;257:679-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 449] [Cited by in RCA: 539] [Article Influence: 41.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Eaden JA, Abrams KR, Mayberry JF. The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2001;48:526-535. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Kim BJ, Yang SK, Kim JS, Jeen YT, Choi H, Han DS, Kim HJ, Kim WH, Kim JY, Chang DK. Trends of ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer in Korea: A KASID study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:667-671. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Jess T, Rungoe C, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Risk of colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:639-645. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Yang SK, Yun S, Kim JH, Park JY, Kim HY, Kim YH, Chang DK, Kim JS, Song IS, Park JB. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in the Songpa-Kangdong district, Seoul, Korea, 1986-2005: a KASID study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:542-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 379] [Cited by in RCA: 383] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Park HC, Shin A, Kim BW, Jung KW, Won YJ, Oh JH, Jeong SY, Yu CS, Lee BH. Data on the characteristics and the survival of korean patients with colorectal cancer from the Korea central cancer registry. Ann Coloproctol. 2013;29:144-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Prideaux L, Kamm MA, De Cruz PP, Chan FK, Ng SC. Inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: a systematic review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1266-1280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Langholz E, Munkholm P, Davidsen M, Binder V. Course of ulcerative colitis: analysis of changes in disease activity over years. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:3-11. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Henriksen M, Jahnsen J, Lygren I, Sauar J, Kjellevold Ø, Schulz T, Vatn MH, Moum B. Ulcerative colitis and clinical course: results of a 5-year population-based follow-up study (the IBSEN study). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:543-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Munie S, Hyman N, Osler T. Fate of the rectal stump after subtotal colectomy for ulcerative colitis in the era of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:408-411. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Ziv Y, Fazio VW, Sirimarco MT, Lavery IC, Goldblum JR, Petras RE. Incidence, risk factors, and treatment of dysplasia in the anal transitional zone after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:1281-1285. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Kariv R, Remzi FH, Lian L, Bennett AE, Kiran RP, Kariv Y, Fazio VW, Lavery IC, Shen B. Preoperative colorectal neoplasia increases risk for pouch neoplasia in patients with restorative proctocolectomy. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:806-12, 812.e1-2. [PubMed] |

| 14. | M’Koma AE, Moses HL, Adunyah SE. Inflammatory bowel disease-associated colorectal cancer: proctocolectomy and mucosectomy do not necessarily eliminate pouch-related cancer incidences. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:533-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zoccali M, Fichera A. Minimally invasive approaches for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6756-6763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Heuschen UA, Hinz U, Allemeyer EH, Autschbach F, Stern J, Lucas M, Herfarth C, Heuschen G. Risk factors for ileoanal J pouch-related septic complications in ulcerative colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis. Ann Surg. 2002;235:207-216. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Lim M, Sagar P, Abdulgader A, Thekkinkattil D, Burke D. The impact of preoperative immunomodulation on pouch-related septic complications after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:943-951. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Morneau M, Boulanger J, Charlebois P, Latulippe JF, Lougnarath R, Thibault C, Gervais N. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for the treatment of colorectal cancer: a literature review and recommendations from the Comité de l’évolution des pratiques en oncologie. Can J Surg. 2013;56:297-310. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Jess T, Loftus EV, Velayos FS, Winther KV, Tremaine WJ, Zinsmeister AR, Scott Harmsen W, Langholz E, Binder V, Munkholm P. Risk factors for colorectal neoplasia in inflammatory bowel disease: a nested case-control study from Copenhagen county, Denmark and Olmsted county, Minnesota. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:829-836. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Sebastian S, Hernández V, Myrelid P, Kariv R, Tsianos E, Toruner M, Marti-Gallostra M, Spinelli A, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, Yuksel ES. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: results of the 3rd ECCO pathogenesis scientific workshop (I). J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:5-18. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Brentnall TA, Crispin DA, Bronner MP, Cherian SP, Hueffed M, Rabinovitch PS, Rubin CE, Haggitt RC, Boland CR. Microsatellite instability in nonneoplastic mucosa from patients with chronic ulcerative colitis. Cancer Res. 1996;56:1237-1240. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Svrcek M, El-Bchiri J, Chalastanis A, Capel E, Dumont S, Buhard O, Oliveira C, Seruca R, Bossard C, Mosnier JF. Specific clinical and biological features characterize inflammatory bowel disease associated colorectal cancers showing microsatellite instability. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4231-4238. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Watanabe T, Konishi T, Kishimoto J, Kotake K, Muto T, Sugihara K. Ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer shows a poorer survival than sporadic colorectal cancer: a nationwide Japanese study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:802-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Choi PM, Zelig MP. Similarity of colorectal cancer in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: implications for carcinogenesis and prevention. Gut. 1994;35:950-954. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Gyde SN, Prior P, Thompson H, Waterhouse JA, Allan RN. Survival of patients with colorectal cancer complicating ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1984;25:228-231. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Ohman U. Colorectal carcinoma in patients with ulcerative colitis. Am J Surg. 1982;144:344-349. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Jensen AB, Larsen M, Gislum M, Skriver MV, Jepsen P, Nørgaard B, Sørensen HT. Survival after colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis: a nationwide population-based Danish study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1283-1287. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Brackmann S, Aamodt G, Andersen SN, Roald B, Langmark F, Clausen OP, Aadland E, Fausa O, Rydning A, Vatn MH. Widespread but not localized neoplasia in inflammatory bowel disease worsens the prognosis of colorectal cancer. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:474-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Shu X, Ji J, Sundquist J, Sundquist K, Hemminki K. Survival in cancer patients hospitalized for inflammatory bowel disease in Sweden. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:816-822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Desai DC, Pellicano R, Shi RH, Sipos F S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Webster JR E- Editor: Wang CH