Published online Feb 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i5.1318

Revised: September 24, 2013

Accepted: September 29, 2013

Published online: February 7, 2014

Processing time: 191 Days and 9.5 Hours

AIM: To analyze the risk factors for biliary stent migration in patients with benign and malignant strictures.

METHODS: Endoscopic stent placement was performed in 396 patients with bile duct stenosis, at our institution, between June 2003 and March 2009. The indications for bile duct stent implantation included common bile duct stone in 190 patients, malignant lesions in 112, chronic pancreatitis in 62, autoimmune pancreatitis in 14, trauma in eight, surgical complications in six, and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) in four. We retrospectively examined the frequency of stent migration, and analyzed the patient factors (disease, whether endoscopic sphincterotomy was performed, location of bile duct stenosis and diameter of the bile duct) and stent characteristics (duration of stent placement, stent type, diameter and length). Moreover, we investigated retrieval methods for migrated stents and their associated success rates.

RESULTS: The frequency of tube stent migration in the total patient population was 3.5%. The cases in which tube stent migration occurred included those with common bile duct stones (3/190; 1.6%), malignant lesions (2/112; 1.8%), chronic pancreatitis (4/62; 6.5%), autoimmune pancreatitis (2/14; 14.3%), trauma (1/8; 12.5%), surgical complications (2/6; 33.3%), and PSC (0/4; 0%). The potential risk factors for migration included bile duct stenosis secondary to benign disease such as chronic pancreatitis and autoimmune pancreatitis (P = 0.030); stenosis of the lower bile duct (P = 0.031); bile duct diameter > 10 mm (P = 0.023); duration of stent placement > 1 mo (P = 0.007); use of straight-type stents (P < 0.001); and 10-Fr sized stents (P < 0.001). Retrieval of the migrated stents was successful in all cases. The grasping technique, using a basket or snare, was effective for pig-tailed or thin and straight stents, whereas the guidewire cannulation technique was effective for thick and straight stents.

CONCLUSION: Migration of tube stents within the bile duct is rare but possible, and it is important to determine the risk factors involved in stent migration.

Core tip: Endoscopic biliary stenting with a tube stent is an accepted therapy for biliary obstruction due to malignant or benign disease. However, stent migration occurs in 5%-10% of patients undergoing biliary stenting. Therefore, it is important to know the factors affecting biliary tube stent migration. We retrospectively examined endoscopic stent placement in 396 patients with bile duct stenosis, and analyzed the frequency of stent migration and the risk factors (patient factors disease, endoscopic sphincterotomy, location of stenosis, diameter of bile duct) and stent factors (duration of placement, type, diameter, length).

- Citation: Kawaguchi Y, Ogawa M, Kawashima Y, Mizukami H, Maruno A, Ito H, Mine T. Risk factors for proximal migration of biliary tube stents. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(5): 1318-1324

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i5/1318.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i5.1318

Endoscopic biliary stenting using a tube stent is an accepted therapy for biliary obstruction developing secondary to malignant or benign disease[1]. The complication rate associated with biliary stent use reportedly ranges from 8% to 10%[2-4], and the described complications include cholangitis, cholecystitis, duodenal perforation, bleeding, pancreatitis, stent fracture, proximal stent migration, distal stent dislocation, and stent occlusion resulting in recurrent biliary obstruction[5-16]. Stent migration is a rare complication associated with biliary stenting[11,17,18]. Most tube stents are pig-tailed shaped with flaps at each end, to prevent proximal or distal migration. However, stents may migrate proximally or distally as a late complication of endoscopic stenting in 5%-10% of patients who have undergone biliary stenting[19]. Proximal stent migration can cause biliary obstruction and cholangitis, thus requiring retrieval or re-stenting. Therefore, it is important to determine the factors influencing biliary tube stent migration that have not yet been documented. A few studies have reported on the risks of stent migration[17]. Johanson et al[17] reported that stent migration occurs in cases of cholangiocarcinoma, larger diameter stents, and short stents. In addition, they concluded that the reason for migration was malignant stricture of the bile duct or, in cases of benign disease, advancement of a stricture that was previously present. In addition, the presence of multiple stents, a broken stent, and differences in physical constitution are proposed as factors causing stent migration. The retrieval of migrated stents is technically challenging, but may usually be achieved endoscopically, by using forceps, snare, or balloon techniques, and rarely requires surgical intervention[18,20-22]. In the present study, we aimed to determine the frequency of biliary stent migration; analyze the risk factors for proximal stent migration; and describe the methods used for retrieval of migrated stents.

Between June 2003 and March 2009, endoscopic stent placement was performed in 396 patients with bile duct stenosis at our institution. The diseases requiring bile duct stenting included common bile duct stones in 190 patients, malignant lesions in 112, chronic pancreatitis in 62, autoimmune pancreatitis in 14, trauma in eight, surgical complications in six, and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) in four (Table 1).

| Diseases | n | Migrated | Non migrated |

| Benign | 227 | 12 | 215 |

| Common bile duct stone | 133 | 3 | 130 |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 62 | 4 | 58 |

| Autoimmune pancreatitis | 14 | 2 | 12 |

| Trauma | 8 | 1 | 7 |

| Post operation | 6 | 2 | 4 |

| PSC | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Malignant | 169 | 2 | 167 |

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was performed using a JF-240, JF-260V, or TJF-260V unit (Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) with the patient under conscious sedation with diazepam and pethidine. We attempted to place a guidewire (Jagwire High Performance Guidewire; Boston Scientific, Natick MA, United States) across the stenotic lesion. After the guidewire was successfully placed across the stenotic lesion, intraductal ultrasonography, brushing cytology, bile juice cytology, and biopsy were performed to diagnose the disease on a case-by-case basis.

In the case of severe stenosis, the stenotic lesions were dilated with a dilation catheter (6-, 7-, or 9-Fr, Soehendra Biliary Dilation Catheter; Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, United States) or a dilation balloon catheter (diameter: 6 mm, length: 2 cm; Hurricane TM RX Balloon Dilation Catheter; Boston Scientific).

After dilation, a pig-tail shaped (Cook Medical) or a straight stent (Double layer stent; Olympus Medical Systems) was implanted in the stenotic lesion; the stents included 7- or 10-Fr polyethylene stents with multiple side holes. A bile duct stent was implanted to drain the bile juice and dilate the stenotic lesions of the bile duct. In cases involving common bile duct stones, a temporary stent was implanted in cases with residual stones, and residual stone removal was postponed until the next procedure.

We defined stent migration in the present study as proximal migration of the stent into the bile duct.

We retrieved the migrated stents by using a basket catheter (4 or 8 wires), snare catheter, rat-toothed forceps, biopsy forceps, balloon catheter, or stent retriever.

We retrospectively examined the frequency of stent migration, and analyzed the patient factors [disease, whether endoscopic sphincterectomy (EST) was performed, location of bile duct stenosis, diameter of the bile duct] and stent factors (duration of stent placement, stent type, diameter and length). We also investigated the retrieval methods for migrated stents and their success rates.

Results were expressed as means or as a percentage of the total number of patients. The Mann-Whitney U test and the χ2 test were used to compare differences between the two groups. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant. All analyses were performed using statistical software (Stat View Ver.5.0; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States).

The frequency of stent migration was 3.5% (14/396) (Table 1). Stent migration occurred in cases with common bile duct stones (3/190; 1.6%), malignant lesions (2/112; 1.8%), chronic pancreatitis (4/62; 6.5%), autoimmune pancreatitis (2/14; 14.3%), trauma (1/8; 12.5%), surgical complications (2/6; 33.3%) and PSC (0/4; 0%) (Table 1).

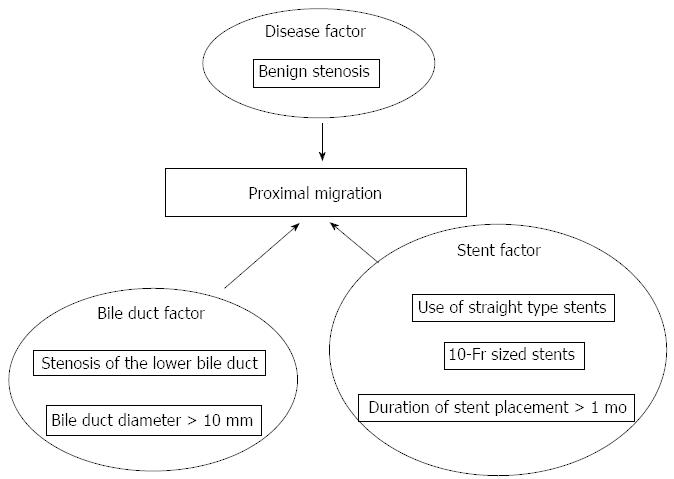

Disease (benign or malignant): In total, 12 of 14 cases (85.7%) of stent migration had benign disease. The overall number of cases with benign disease in this series was 227/396 (57.3%). The frequency of migration was significantly higher in cases with benign disease, such as chronic pancreatitis and autoimmune pancreatitis, when compared with cases of malignant disease (P = 0.030) (Figure 1, Table 2).

| Diseases | n | Migrated | Non migrated | P value |

| Benign | 227 | 12 | 215 | 0.03 |

| Malignant | 169 | 2 | 167 | |

| EST | 263 | 11 | 252 | 0.400 |

| Non EST | 133 | 3 | 130 | |

| Low | 156 | 10 | 146 | 0.031 |

| Hilar or middle | 107 | 1 | 106 | |

| Bile duct > 10 mm | 154 | 11 | 143 | 0.023 |

| Bile duct ≤ 10 mm | 135 | 2 | 133 | |

| ≤ 1 m | 263 | 4 | 259 | 0.007 |

| > 1 m | 133 | 10 | 123 |

Cases undergoing EST: In total, 11 of 14 cases (78.6%) of stent migration had previously undergone EST. The overall number of cases who had undergone EST in this series was 263/396 (66.4%). The frequency of migration was not significantly higher in cases who had undergone EST when compared with cases who had not undergone EST (P = 0.40) (Table 2).

Location of bile duct stenosis: Among the cases with bile duct stenosis, except for cases with common bile duct stones, stenosis of the lower common bile duct was noted in 10 of the 11 cases (90.9%) with stent migration. Among the total number of cases with bile duct stenosis in the series, stenosis of the lower common bile duct was noted in 156 of 263 cases (59.3%). The frequency of migration was significantly higher in cases with stenosis of the lower common bile duct when compared with cases with hilar stenosis or stenosis of the middle common bile duct (P = 0.031) (Figure 1, Table 2).

Bile duct diameter: Among the cases of stenosis of the lower bile duct, except for those with hilar stenosis or stenosis of the middle bile duct, a bile duct diameter > 10 mm was noted in 11 of 13 cases (84.6%) of stent migration. The overall number of patients with a bile duct diameter > 10 mm was 154/289 (53.3%). The frequency of migration was significantly higher in cases with a bile duct diameter > 10 mm when compared with cases with a bile duct diameter ≤ 10 mm (P = 0.023) (Figure 1, Table 2).

Duration of stent placement: Stent placement duration > 1 mo was noted in 10 of 14 cases (71.4%) of stent migration. The number of patients with stent placement duration > 1 mo in the series was 133/396 (33.6%). The frequency of migration was significantly higher in cases with stent placement duration > 1 mo when compared with ≤ 1 mo (P = 0.007) (Figure 1, Table 2).

Stent shape: Straight-type stents were used in 11 of 14 cases (72.7%) of stent migration. The overall number of patients receiving straight-type stents was 133/396 (33.6%). The frequency of migration was significantly higher in cases with straight-type stents when compared with pig-tailed stents (P < 0.001) (Figure 1, Table 3).

| Stent | Factor | n | Migrated | Non migrated | P value |

| Stent shape | Pig-tail | 263 | 3 | 260 | < 0.001 |

| Straight | 133 | 11 | 122 | ||

| Stent diameter | 7 Fr | 280 | 3 | 277 | < 0.001 |

| 10 Fr | 116 | 11 | 105 | ||

| Stent length | 5 cm | 108 | 5 | 103 | 1.000 |

| 0.530 | |||||

| 7 cm | 270 | 8 | 262 | 2.000 | |

| > 0.990 | |||||

| 9 cm | 18 | 1 | 17 | 3.000 | |

| 0.450 |

Stent diameter: In total, 11 of 14 cases (78.6%) of stent migration received a 10-Fr stent. The overall number of patients who received a 10-Fr stent was 116/396 (29.3%). The frequency of migration was significantly higher in cases with 10-Fr stents compared with 7-Fr stents (P < 0.001) (Figure 1, Table 3).

Stent length: A 5-, 7- and 9-cm stent was used in 5/14 (57.1%), 8/14 (57.1%) and 1/14 (7.1%) cases of stent migration, respectively. The overall number of patients who received a 5-, 7- and 9-cm stent was 108/396 (27.3%), 270/396 (68.2%) and 18/396 (4.5%), respectively. No significant differences in the frequency of migration were noted among the patients who received 5-, 7- and 9-cm stents (Table 3).

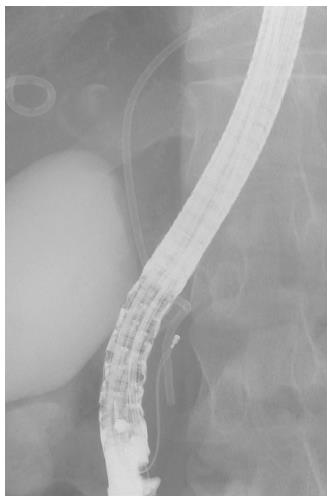

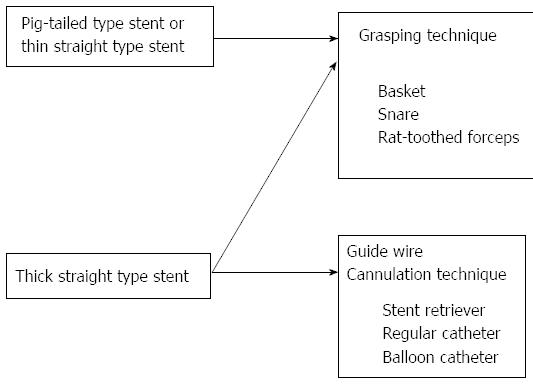

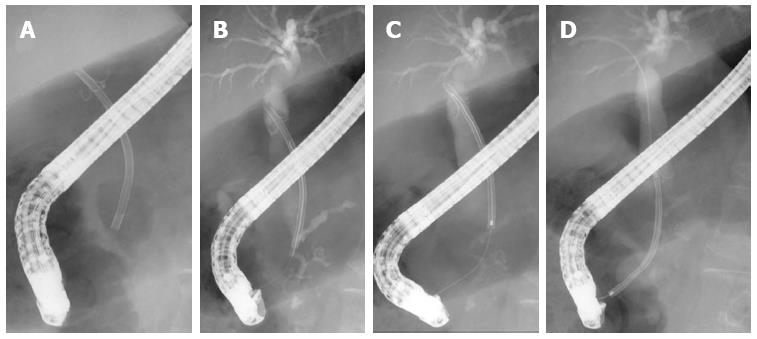

The grasping technique was used in eight of 14 (57.1%) cases of stent migration, and 60% of the cases had 7-Fr pig-tail stents. This is a technique of retrieval that is attempted by directly grasping the distal end of the stent with a basket (Figure 2), a snare, rat-toothed forceps or biopsy forceps. This method is effective for pig-tailed or thin straight stents (Figure 3). The cannulation technique was used in six of 14 (42.9%) cases of stent migration, and all cases had 10-Fr straight stents. This is a technique of retrieval that is attempted by connecting the distal end of the stent with a stent retriever, a balloon catheter, and a cannula (Figure 4) by using the guidewire passed through the lumen of the migrated stent. This method is effective for thick straight stents (Figure 3). Stent retrieval was successful in all cases.

Endoscopic biliary stenting using a tube stent is now a well-established therapy for biliary obstruction developing secondary to malignant or benign disease[1]. However, certain complications may develop with this technique and should be carefully considered. The complication rate for biliary stents reportedly ranges from 8% to 10%[2-4], and the complications include cholangitis, cholecystitis, duodenal perforation, bleeding, pancreatitis, stent fracture, proximal stent migration, distal stent dislocation, and stent occlusion resulting in recurrent biliary obstruction[5-16]. Stent migration, a rare complication associated with biliary stenting[7,8,12], is a late event following endoscopic stenting. It occurs in 5%-10% of patients who undergo biliary stenting, and may involve proximal or distal migration[7,8,15,17,18,20,23-28]. Previous studies have reported that 3.1%-4.9% and 3%-6% of patients undergoing biliary stenting experience proximal and distal stent migration, respectively[5,7,17,18,24,25,29,30]. In the present study, the frequency of stent migration was 3.5%, which is consistent with previous studies.

Stent migration can lead to symptoms of biliary obstruction, therefore, it is important to determine the risk factors of stent migration[17,20,31]. However, thus far, the risk factors for biliary stent migration have yet to be clarified. Arhan et al[32] reported that proximal stent migration occurs in cases with cholangiocarcinoma, short stents, or stents with large diameters. Moreover, the placement of multiple stents and breaking of stents may cause stent migration. In addition to these risk factors, we also analyzed other possible risk factors including subtypes of both benign and malignant biliary disease; EST use; location of the stenosis; duration of stent placement; and stent shape, diameter, and length.

A previous study has indicated that stent displacement is less frequently noted in malignant than in benign biliary stenosis, which may be attributed to the tight covering of the stents by malignant tissue[32]. Similarly, in the present study, the frequency of migration was significantly higher in cases of benign than malignant disease (P = 0.030). One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that stenosis in benign disease is not as tight as that in malignant disease, which may be due to differences in the resolution of local inflammation. In cases of malignant stenosis, tumor growth may help to anchor the stent, thus preventing its migration. Arhan et al[32] reported that stent migration was observed less frequently in post-cholecystectomy strictures than in other benign biliary stenosis, except in cases of PSC[32]; the authors had indicated that the tightness of the fibrotic stricture could be a possible explanation for this finding. However, it was difficult to assess these hypotheses due to the low number of available cases in the present study.

Data on whether undergoing an EST before placement of a biliary stent affects the risk of migration are scarce. EST did not significantly affect the frequency of stent migration in previous studies[17,27,29,33]. Similarly, in the present study, the frequency of stent migration was not significantly higher in the cases who had undergone EST compared to those who had not undergone EST (P = 0.40). However, one study indicated a higher frequency of stent migration in patients who had undergone stent placement without prior EST compared to patients who had undergone stent placement after undergoing EST. The higher migration rate in these patients was primarily because of distal migration, whereas the incidence of proximal stent migration was not influenced by EST[34]. Thus, undergoing EST prior to stent placement cannot be considered as a proven risk factor for proximal stent migration.

With regard to stricture location, we generally believe that distal stent dislocation occurred more frequently in cases with stenosis of the upper bile duct, whereas proximal stent migration occurred more frequently in those with stenosis of the lower bile duct. In the present study, the frequency of migration was significantly higher in cases with stenosis of the lower common bile duct when compared with hilar stenosis or stenosis of the middle common bile duct (P = 0.031). However, in cases with stenosis of the lower common bile duct, it was unclear whether the migration was related to stent length.

We believe that a greater amount of space in the proximal bile duct is necessary for migration. Therefore, we hypothesized that the stent would be more likely to migrate proximally in cases with a larger bile duct diameter. In the present study, the frequency of migration was significantly higher in cases with a bile duct diameter > 10 mm compared with ≤ 10 mm (P = 0.023).

Moreover, in the present study, the frequency of migration was also significantly higher in cases with stent placement duration > 1 mo compared with ≤ 1 mo (P = 0.007). A longer duration of stent placement increased the risk of migration. Therefore, we suggest that the stents should be exchanged or removed after a short placement interval.

Biliary stent design may also affect the risk for migration. With regard to stent shape, we used pig-tailed shaped and straight tube stents only in the present study. Straight tube stents have been modified with side flaps or barbs to decrease the risk of migration[35]. Pig-tailed shaped stents were also used to decrease the risk of migration. In the present study, the frequency of stent migration was significantly higher in cases with straight-type stents when compared with pig-tailed stents (P < 0.001). We noted that the presence of side flaps or barbs was not sufficient to prevent stent migration. The diameter and length of the stents may also be associated with the risk of migration[17]. With regard to stent diameter, in the present study, the frequency of migration was significantly higher in the cases with 10-Fr stents compared with 7-Fr stents (P < 0.001). We believe that, because stenotic lesions of the bile duct were already improved in cases in which thick stents (such as 10-Fr stents) were used, these cases were more likely to experience migration. With regard to stent length, in the present study, no significant differences in the frequency of migration were noted among the patients who had 5-, 7- and 9-cm stents. Arhan et al[32] have reported that shorter stents tend to migrate proximally, whereas longer stents tend to migrate distally, in cases of benign biliary stenosis. Moreover, longer stents in the bile duct are less likely to migrate because a longer portion is fixed in the common bile duct, thus limiting proximal movement[17]. I think that we should pay attention to using shorter and straight stents in high-risk patients. I recommend using pig-tailed type stent for those cases.

Most of the stents that have migrated proximally can be successfully retrieved indirectly, through stone extraction with a balloon catheter, or directly by using various grasping accessories. All the stents were successfully retrieved in the present study, therefore, none of the patients required surgery for stent retrieval. In patients with benign strictures, this favorable finding could be a result of the dilation of the stricture due to further stenting, thereby facilitating the retrieval of the proximally migrated stent.

In conclusion, the risk of stent migration is higher in benign than in malignant biliary stenosis. Proximal migration of biliary or pancreatic stents is an infrequent occurrence. Proximal stent migration was found to be closely associated with benign stenosis, stenosis in the lower common bile duct, bile duct diameter > 10 mm, stent placement duration > 1 mo, straight-type stents, and 10-Fr stents. The migrated stents can be extracted endoscopically, with a high degree of success, using a variety of techniques involving baskets or balloons.

Endoscopic biliary stenting using a tube stent is currently a well-established therapy for biliary obstruction developing secondary to malignant or benign disease. Endoscopic biliary stents may migrate proximally or distally as a late complication in 5%-10% of patients who have undergone biliary stenting. It is important to determine the factors influencing biliary tube stent migration. However, a few studies have reported on the risks of stent migration.

In this study, the frequency of tube stent migration in the total patient population was 3.5%. The potential risk factors for migration included bile duct stenosis secondary to benign disease (P = 0.030); stenosis of the lower bile duct (P = 0.031); bile duct diameter > 10 mm (P = 0.023); duration of stent placement > 1 mo (P = 0.007); use of straight-type stents (P < 0.001); and 10-Fr stents (P < 0.001).

Retrieval of the migrated stents was successful in all cases. This paper describes the methods used for retrieval of migrated stents. The grasping technique, using a basket or snare, was effective for pig-tailed or thin and straight stents, whereas the guidewire cannulation technique was effective for thick and straight stents.

It is important to pay attention to the factors influencing biliary tube stent migration, and know the method for retrieval of migrated stents.

Proximal stent migration is a rare complication associated with biliary stenting. Proximal migration means movement of stent distal end into common bile duct. Proximal stent migration can cause biliary obstruction and cholangitis, thus requiring retrieval or re-stenting.

The potential risk factors for migration included bile duct stenosis secondary to benign disease; stenosis of the lower bile duct; bile duct diameter > 10 mm; duration of stent placement > 1 mo; use of straight-type stents; and 10-Fr stents. It is important to pay attention to these risk factors, and know the method for retrieval of migrated stents. These results are impressive.

| 1. | Soehendra N, Reynders-Frederix V. Palliative bile duct drainage - a new endoscopic method of introducing a transpapillary drain. Endoscopy. 1980;12:8-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Blake AM, Monga N, Dunn EM. Biliary stent causing colovaginal fistula: case report. JSLS. 2004;8:73-75. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Lenzo NP, Garas G. Biliary stent migration with colonic diverticular perforation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:543-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wurbs D. The development of biliary drainage and stenting. Endoscopy. 1998;30:A202-A206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Huibregtse K, Katon RM, Coene PP, Tytgat GN. Endoscopic palliative treatment in pancreatic cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 1986;32:334-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Siegel JH, Snady H. The significance of endoscopically placed prostheses in the management of biliary obstruction due to carcinoma of the pancreas: results of nonoperative decompression in 277 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1986;81:634-641. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Deviere J, Baize M, de Toeuf J, Cremer M. Long-term follow-up of patients with hilar malignant stricture treated by endoscopic internal biliary drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34:95-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Devière J, Devaere S, Baize M, Cremer M. Endoscopic biliary drainage in chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:96-100. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Tarnasky PR, Cunningham JT, Hawes RH, Hoffman BJ, Uflacker R, Vujic I, Cotton PB. Transpapillary stenting of proximal biliary strictures: does biliary sphincterotomy reduce the risk of postprocedure pancreatitis? Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:46-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lee MJ, Mueller PR, Saini S, Morrison MC, Brink JA, Hahn PF. Occlusion of biliary endoprostheses: presentation and management. Radiology. 1990;176:531-534. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Mueller PR, Ferrucci JT, Teplick SK, vanSonnenberg E, Haskin PH, Butch RJ, Papanicolaou N. Biliary stent endoprosthesis: analysis of complications in 113 patients. Radiology. 1985;156:637-639. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Walta DC, Fausel CS, Brant B. Endoscopic biliary stents and obstructive jaundice. Am J Surg. 1987;153:444-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Neuhaus H. Endoscopic tumor therapy. Endoscopy. 1989;21 Suppl 1:357-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lowe GM, Bernfield JB, Smith CS, Matalon TA. Gastric pneumatosis: sign of biliary stent-related perforation. Radiology. 1990;174:1037-1038. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Lahoti S, Catalano MF, Geenen JE, Schmalz MJ. Endoscopic retrieval of proximally migrated biliary and pancreatic stents: experience of a large referral center. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:486-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Baty V, Denis B, Bigard MA, Gaucher P. Sigmoid diverticular perforation relating to the migration of a polyethylene endoprosthesis. Endoscopy. 1996;28:781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Johanson JF, Schmalz MJ, Geenen JE. Incidence and risk factors for biliary and pancreatic stent migration. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:341-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tarnasky PR, Cotton PB, Baillie J, Branch MS, Affronti J, Jowell P, Guarisco S, England RE, Leung JW. Proximal migration of biliary stents: attempted endoscopic retrieval in forty-one patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:513-520. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Huibregtse K. Endoscopic biliary and pancreatic drainage. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers 1988; 93-120. |

| 20. | Culp WC, McCowan TC, Lieberman RP, Goertzen TC, LeVeen RF, Heffron TG. Biliary strictures in liver transplant recipients: treatment with metal stents. Radiology. 1996;199:339-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Jendresen MB, Svendsen LB. Proximal displacement of biliary stent with distal perforation and impaction in the pancreas. Endoscopy. 2001;33:195. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Liebich-Bartholain L, Kleinau U, Elsbernd H, Büchsel R. Biliary pneumonitis after proximal stent migration. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:382-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chaurasia OP, Rauws EA, Fockens P, Huibregtse K. Endoscopic techniques for retrieval of proximally migrated biliary stents: the Amsterdam experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:780-785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Schmalz MJ, Johanson JF, Geenen JE, Venu RP, Johnson GK. Migrated biliary and pancreatic stents; complications and techniques for retrieval. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:252 Available from: http://www.giejournal.org/. |

| 25. | Lammer J. Biliary endoprostheses. Plastic versus metal stents. Radiol Clin North Am. 1990;28:1211-1222. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Ahlström H, Lörelius LE, Jacobson G. Inoperable biliary obstruction treated with percutaneously placed endoprosthesis. Acta Chir Scand. 1986;152:301-303. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Davids PH, Groen AK, Rauws EA, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Randomised trial of self-expanding metal stents versus polyethylene stents for distal malignant biliary obstruction. Lancet. 1992;340:1488-1492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 753] [Cited by in RCA: 702] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | De Palma GD, Catanzano C. Stenting or surgery for treatment of irretrievable common bile duct calculi in elderly patients? Am J Surg. 1999;178:390-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Güitrón A, Adalid R, Barinagarrementería R, Gutiérrez-Bermúdez JA, Martínez-Burciaga J. [Incidence and relation of endoscopic sphincterotomy to the proximal migration of biliary prostheses]. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2000;65:159-162. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Alfredo G, Raúl A, Barinagarrementeria R, Gutiérrez-Bermúdez JA, Martínez-Burciaga J. [Proximal migration of biliary prosthesis. Endoscopic extraction techniques]. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2001;66:22-26. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Nakamura T, Hirai R, Kitagawa M, Takehira Y, Yamada M, Tamakoshi K, Kobayashi Y, Nakamura H, Kanamori M. Treatment of common bile duct obstruction by pancreatic cancer using various stents: single-center experience. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2002;25:373-380. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Arhan M, Odemiş B, Parlak E, Ertuğrul I, Başar O. Migration of biliary plastic stents: experience of a tertiary center. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:769-775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Giorgio PD, Luca LD. Comparison of treatment outcomes between biliary plastic stent placements with and without endoscopic sphincterotomy for inoperable malignant common bile duct obstruction. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1212-1214. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Margulies C, Siqueira ES, Silverman WB, Lin XS, Martin JA, Rabinovitz M, Slivka A. The effect of endoscopic sphincterotomy on acute and chronic complications of biliary endoprostheses. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:716-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Barton RJ. Migrated double pigtail biliary stent causes small bowel obstruction. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:783-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewers: Losanoff JE, Zhang SJ, Zhang XW S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Kerr C E- Editor: Wu HL