Published online Dec 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i48.18487

Revised: August 18, 2014

Accepted: October 15, 2014

Published online: December 28, 2014

Processing time: 184 Days and 22.7 Hours

Colonic mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas are a rare occurrence and the definitive treatment has not been established. Solitary or multiple, elevated or polypoid lesions are the usual appearances of MALT lymphoma in the large intestine and sometimes the surface may reveal abnormal vascularity. Herein, we report a case of MALT lymphoma and review the relevant literature. Upon colonoscopy, a suspected pathologic lesion was observed in the proximal transverse colon. The lesion could be distinguished more prominently after using narrow-band imaging mode and indigo carmine-dye spraying chromoendoscopy. Histopathologic examination of this biopsy specimen revealed lymphoepithelial lesions with diffuse proliferation of atypical lymphoid cells effacing the glandular architecture and centrocyte-like cells infiltrating the lamina propria. Immunohistochemical analyses showed that tumor cells were positive for CD20 and Bcl-2e, and negative for CD10, CD23, and Bcl-6. According to Ann-Arbor staging system, the patient had stage IIE. A partial colectomy with dissection of the paracolic lymph nodes was performed. Until now, there is no recurrence of lymphoma at follow-up.

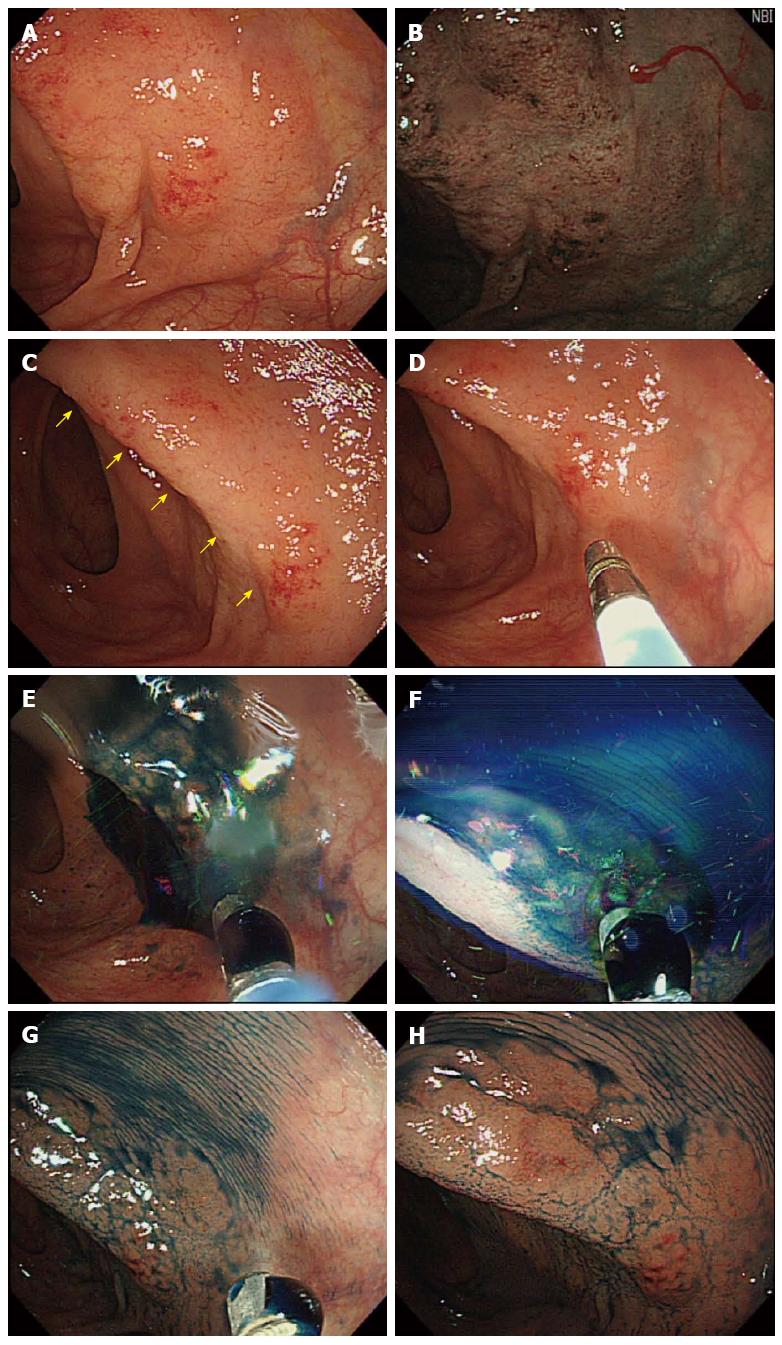

Core tip: Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma in the large intestine is a rare disease, but it is a clinically important condition that requires proper evaluation. Most of the colonic MALT lymphomas mainly present as a protruding and/or ulcerative lesion, and rarely present as a flat lesion. It is not easy to detect MALT lymphoma of the flat type and could be misdiagnosed. Thus, greater attention is needed for the detection and differential diagnosis of these lesions. The narrow-band imaging mode plus indigo carmine-dye spraying chromoendoscopy or/and endoscopic biopsy may be helpful for making the diagnosis.

- Citation: Seo SW, Lee SH, Lee DJ, Kim KM, Kang JK, Kim DW, Lee JH. Colonic mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma identified by chromoendoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(48): 18487-18494

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i48/18487.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i48.18487

Lymphomas are malignancies of the lymphatic system, of which one type is mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. Since the term MALT lymphoma was first introduced by Isaacson and Wright[1] in 1983, it has been widely used. Recently, MALT was categorized as extranodal marginal zone B cell lymphoma by the World Health Organization. Although MALTs are found in many parts of the body, the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is the most predominant site[2]. Therefore, the alimentary tract is the most common location of extranodal lymphomas including MALT lymphoma. The stomach and small bowel are the sites for 50%-60% and 20%-30% of GI lymphomas, respectively. Colorectal lymphomas account for only 15%-20% of GI lymphomas[3], 1.4% of all non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas[4], and < 1% of colorectal malignant tumors[5]. Colorectal MALT lymphoma is a rare disease, which accounts for a small proportion of both colorectal malignancies and GI lymphomas. Due to the rarity of the disease, colorectal MALT lymphomas have not been well investigated.

There are various identifying colonoscopic features of MALT lymphoma in the large intestine. Most of the colonic MALT lymphomas mainly present as a protruding and/or ulcerative lesion, and rarely present as a flat lesion[6]. Flat pathologic lesions in the large intestine are difficult to identify, but can appear as a discoloration, and/or diffuse granularity, and/or loss of vascularity. Herein, we report a case of an asymptomatic patient with MALT lymphoma that was detected accidentally during colonoscopy screening for colorectal cancer. The lesion manifested as a diffuse loss of vascularity and was identified by narrow-band imaging (NBI) mode and indigo carmine-dye spraying chromoendoscopy.

An asymptomatic 64-year-old man with a family history of colorectal cancer visited our hospital for a routine medical check-up including upper GI endoscopy and colonoscopy for surveillance of GI cancer. He had dyslipidemia that was well controlled with medications, but he had no other medical illness or surgical history. The patient had been a smoker (10-15 cigarettes/d) since the age of 30 years. However, he never drank alcohol.

On general examination, the patient did not look sick, but he was slightly thin (height, 165.3 cm; weight, 47.2 kg; waist circumference 70.1 cm; body mass index, 17.3 kg/m2). The patient’s initial vital signs were a blood pressure of 95/60 mmHg, a regular heart rate of 62 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 15 breaths/min, and a body temperature of 36.2 °C. Other physical examinations including that of the abdomen were unremarkable. The results of all laboratory tests such as complete blood cell count, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, protein, albumin, electrolyte, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, electrolyte, lipid profile (total cholesterol, triglyceride, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol), fasting glucose, urine analysis, and stool examination, were within their normal limits. Also, although the abdominal ultrasonography showed a small 3 mm benign gall bladder polyp, other radiologic evaluations, including chest X-ray, abdomen supine/erect X-ray, did not show any abnormal findings.

Due to the benefits of same-day bidirectional endoscopy (shorter hospital stay, fewer hospital visits, and reduced medical costs compared to alternate-day endoscopy), we decided to perform same-day bidirectional endoscopy, esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) followed by colonoscopy. He underwent bowel preparation using 3 L of polyethylene glycol solution (Colyte-F; Taejoon Pharmaceutical Co., Seoul, South Korea) on the day before and 1 L on the day of colonoscopy. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient. The endoscopic examinations (EGD, colonoscopy) were performed under conscious sedation with combinations of intravenous midazolam (Dormicum; Hoffman-La Roche AG, Basel, Switzerland) and propofol (Pofol; Jeil Pharmaceutical Co., Seoul, South Korea). Also, an antispasmodic agent, cimetropium bromide (Algiron; Green-Cross Pharmaceutical Co., Yongin, Gyeonggi-do, South Korea), was given intravenously immediately before the procedure to prevent upper and lower GI movements, which can interfere with a detailed and complete inspection. The endoscopist performed the procedure in the patient with an Olympus video endoscope (Olympus Optical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), GIF-H260 for EGD and CF-H260L for colonoscopy, respectively. During the endoscopic procedure, the patient’s blood pressure, pulse, and oxygen saturation were monitored.

The EGD findings were unremarkable, except for chronic atrophic gastritis. In the colonoscopic examination, a suspected pathologic lesion (diffuse granularity of the mucosa with loss of vascularity) was observed in the proximal transverse colon (Figure 1A). After using the NBI mode, this lesion was distinguished more prominently from the surrounding normal colonic mucosa and it showed an abnormal branch-like capillary pattern in patches (Figure 1B). Also, after indigo carmine-dye spraying (Figure 1C-F), this lesion was distinguished more prominently (Figure 1G, H). A punch biopsy was performed in this lesion and the specimen was sent for histopathologic examination.

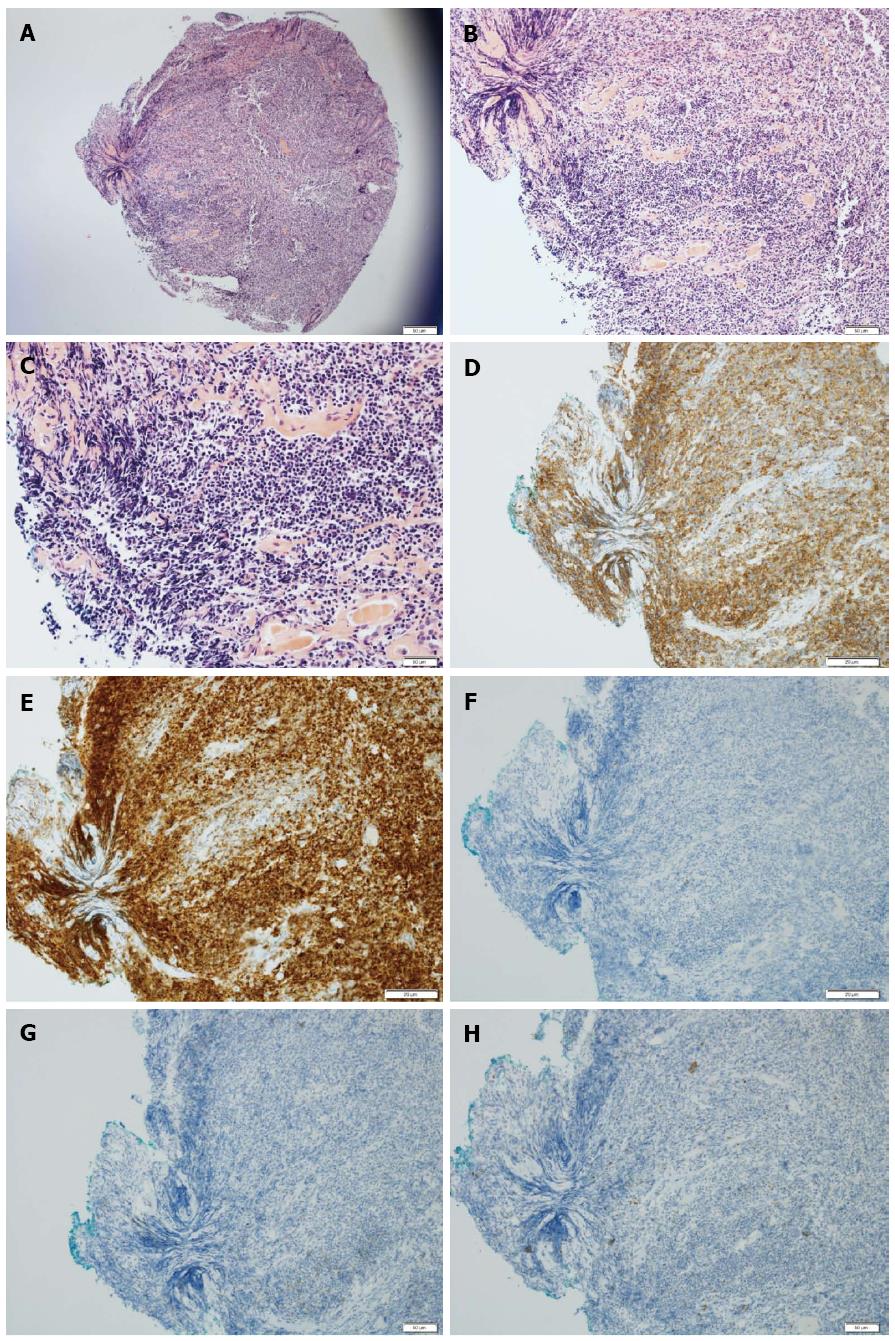

Histopathologic examination of this biopsy specimen with hematoxylin-eosin stain revealed lymphoepithelial lesions with diffuse proliferation of atypical lymphoid cells effacing the glandular architecture and centrocyte-like cells infiltrating the lamina propria (Figure 2A-C). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for Bcl-2 and CD20 (Figure 2D, E), and negative for CD10, CD23 and Bcl-6 (Figure 2F-H). These findings were compatible with a diagnosis of MALT lymphoma.

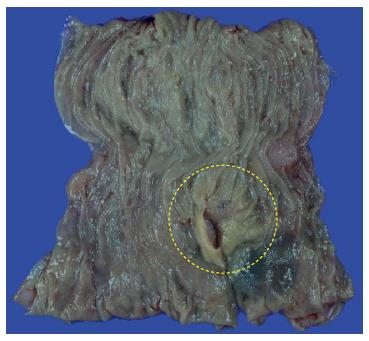

Further evaluation was performed to assess of the stage and metastasis of the lymphoma. There was no evidence of distant lymph node metastasis or any other organ involvement on thoracic and abdominal CT, and positron emission tomography (PET) scans. Urea-breath test for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection was negative. In our case, the stage of colonic MALT lymphoma was IIE according to the Ann-Arbor staging system. A partial colectomy with dissection of the paracolic lymph nodes was performed. Resected specimens (Figure 3) were histologically and immunohistochemically reconfirmed to be MALT lymphoma with adjacent nodal involvement. The patient is being followed-up at our outpatient clinics with colonoscopy, thoracic and abdominal CT, and PET scans, and he is still alive without any recurrence of the disease at 12 mo after the diagnosis.

Lymphomas are malignancies of the lymphatic system with a wide variety of histologic subtypes and a broad spectrum of clinical behaviors, aggressiveness, and prognosis. Lymphomas can be largely classified as non-Hodgkin’s or Hodgkin’s lymphoma[4]. MALT lymphoma is a subtype of non-Hodgkin’s, which is a precursor B cell neoplasm[7]. MALT is diffusion system of small concentrations of lymphoid tissue. Although the predominant site of these tissues is the GI tract, they are also found in various parts of the body such as the lung, thyroid, breast, synovium, lacrimal and salivary glands, orbit, dura, skin and soft tissues[8-18]. MALTs are populated by lymphocytes such as T and B cells, as well as plasma cells and macrophages. They play an important role in normal mucosal regeneration and immune response to specific antigens encountered all along the mucosal surface[19]. However, cells in MALT may occasionally undergo abnormal proliferation, i.e., carcinogenesis, and give rise to lymphoma of the MALT type[20].

The GI tract is the primary site of extranodal lymphoma involvement, though colorectal MALT lymphomas are rarer than those arising from the stomach or small intestine. It has been reported that only 2.5% of all MALT lymphomas originate from the colon[21]. Although the epidemiology of MALT lymphoma in large intestine has not been established due to their rarity, most patients were approximately 60 years-old, with similar numbers of men and women[22,23]. The clinical presentation of MALT lymphoma varies, and may present with generalized symptoms of weight loss, fever, abdominal pain, chronic fatigue, nausea, and hematochezia[24]. However, MALT lymphomas of the GI tract are usually asymptomatic, as in the case presented here, because they are localized and slow-growing.

The majority of colorectal lymphomas are found in the cecum or ascending colon, and > 70% are proximal to the hepatic flexure[3]. In our patient, the MALT lymphoma was also located in the proximal transverse colon near to the end of the ascending colon (hepatic flexure). When grossly visible by colonoscopy, MALT lymphomas are mostly observed as a single mass and the appearance of the lesion is generally protruding and ulcerative[22]. In contrast, colonoscopic examination of the current patient revealed a flat lesion with diffuse granularity of the mucosa and loss of vascularity. Even for experienced endoscopists, flat lesions are more difficult to detect than protruding or ulcerative lesions. In our case, there was difficulty in differentiating the lesion from the surrounding mucosa. Therefore, we could have missed the lesion if we had not used NBI mode and/or chromoendoscopy during colonoscopy[6,25].

Microscopically, MALT lymphomas usually appear as lymphoepithelial lesions with irregular nuclei and hyperchromasia[5,26,27]. Similar formations involving reactive lymphoid infiltrates may also appear in benign conditions involving inflammation. However, lymphoid cells of MALT lymphoma may expand in the lamina propria and occasionally infiltrate the muscularis mucosa, which may be manifested as mucosal ulcers. In our case, atypical lymphoid cells and centrocyte-like cells infiltrating through the lamina propria were noted. Immunohistochemical analyses can distinguish MALT lymphoma from other low-grade lymphomas by detecting positivity for superficial Ig and pan B antigens (CD19, CD20, CD79) without expression of CD5, CD10, CD23, and cyclin D1 (Bcl-1)[18,28]. Tumor cells of MALT lymphoma are also positive for Bcl-2 and negative for Bcl-6[18]. In the present case, the immunohistochemical results of the colonic lesion were positive for CD20 and Bcl-2 and negative for CD10, CD23, and Bcl-6.

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, including MALT-type, can be evaluated using the Ann-Arbor Staging Classification[29,30], which focuses on the number of tumor sites (nodal vs extranodal), location, and the presence or absence of systemic B symptoms (weight loss, night sweating, unexplained persistent or recurrent fever). In the present case, the patient was evaluated by chest and abdominal CT and torso-PET. The result of surgical biopsy showed MALT lymphoma with regional lymph node involvement. Thus, the stage was IIE in our patient according to the Ann-Arbor System (single extranodal site and involvement of adjacent lymph nodes).

Although the pathogenesis of MALT lymphoma has yet to be clearly elucidated, several etiologic factors have been postulated to explain this rare disease: (1) chromosomal abnormalities including trisomy 3 and translocations (t[11;18][q21;q21], t[14;18][q32;q21], t[1;14][p22;q32], t[3;14][p13;q32])[31-33]; (2) autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren’s syndrome, relapsing polychondritis, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Wegener’s granulomatosis[34-36]; (3) immunodeficiency and immunosuppression; iv) celiac disease[37]; (4) inflammatory bowel disease, including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis[38,39]; and (5) bacterial infection such as H. pylori, Borrelia afzelii, Campylobacter jejuni, Chlamydia psittaci, and Mycobacterium species[19,40-42]. Notably, more than 90% of MALT lymphomas of the stomach are associated with H. pylori infections[43]. According to numerous reports, H. pylori eradication often results in an excellent remission in patients with gastric MALT lymphomas. However, the treatment of colonic lymphoma is still inconclusive. Hence, further studies will be needed to clarify the efficacy of the eradication of H. pylori for treatment of colonic MALT lymphoma.

Because of the lack of a definite etiology and the rarity of the disease, the treatment of colorectal MALT lymphoma is still debated[44,45]. In the absence of a standardized treatment, various methods have been used, including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation. However, data suggest both surgery and chemotherapy as a first step therapy in patients with MALT lymphoma of the large intestine[45]. The colorectal regions are particularly susceptible to complications of radiation therapy, and therefore external beam radiation is not a preferred option. Thus, some advocate that surgical resection might be the best choice[46,47]. In clinical practice, most cases of locally extended MALT lymphoma, such as in our patient, are treated by surgical resection. However, recent studies show that chemotherapy alone can be effective for colorectal MALT lymphoma[48,49]. Additionally, chemotherapy has the advantage of organ preservation and is effective for micro-metastasis[45]. The CHOP-regimen (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) is well known as the first-line and mainstay chemotherapy for colorectal lymphoma. However, further large-scale studies are required to establish the standard strategy of treatment for this disease. Unfortunately, the majority of patients with primary colorectal lymphoma ultimately have recurrences and die from their disease[8,50]. Because most of these cases are low-grade and less aggressive, their five-year overall survival rate (range: 55%-79%) is relatively higher than other types of colorectal lymphoma[24,26,51,52].

In conclusion, colonic MALT lymphoma is a rare occurrence, but is a clinically important condition that requires proper evaluation for guiding therapy. Additionally, it is not easy to detect MALT lymphoma of the flat type and could be misdiagnosed. Thus, greater attention is needed for the detection and differential diagnosis of these lesions. The NBI mode plus indigo carmine-dye spraying chromoendoscopy and/or endoscopic biopsy may be helpful for making the diagnosis.

An asymptomatic 64-year-old man with a family history of colorectal cancer visited our hospital for a routine medical check-up including upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and colonoscopy.

Colonic mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma.

This lesion should be differentiated from other colonic lesions such as adenocarcinoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumor, and amyloidosis.

All of the laboratory tests were within normal limits.

The colonoscopic examination revealed a flat lesion with diffuse granularity of the mucosa and loss of vascularity.

Hematoxylin-eosin staining revealed atypical lymphoid cells and centrocyte-like cells infiltrating through the lamina propria. In addition, the immunohistochemical analyses of the lesion were positive for CD20 and Bcl-2, and negative for CD10, CD23, and Bcl-6.

A partial colectomy including the pathologic lesion and dissections of the paracolic lymph nodes were performed.

Because of the lack of a definite etiology and the rarity of the disease, the treatment of colorectal MALT lymphoma is still debated.

Narrow-band imaging mode is an imaging technique for endoscopic examination, where light of specific blue and green wavelengths is used to enhance visualization of certain mucosal details.

More attention should be paid to the detection of colonic MALT lymphoma, for which narrow-band imaging mode and indigo carmine-dye spraying chromoendoscopy may be useful for establishing the diagnosis.

The article presents the detailed clinical features, endoscopic and histologic findings, diagnostic procedure, and treatment strategy of colonic MALT lymphoma with a flat lesion.

| 1. | Isaacson P, Wright DH. Malignant lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. A distinctive type of B-cell lymphoma. Cancer. 1983;52:1410-1416. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Koch P, del Valle F, Berdel WE, Willich NA, Reers B, Hiddemann W, Grothaus-Pinke B, Reinartz G, Brockmann J, Temmesfeld A. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: II. Combined surgical and conservative or conservative management only in localized gastric lymphoma--results of the prospective German Multicenter Study GIT NHL 01/92. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3874-3883. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Koch P, del Valle F, Berdel WE, Willich NA, Reers B, Hiddemann W, Grothaus-Pinke B, Reinartz G, Brockmann J, Temmesfeld A. Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: I. Anatomic and histologic distribution, clinical features, and survival data of 371 patients registered in the German Multicenter Study GIT NHL 01/92. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3861-3873. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Doolabh N, Anthony T, Simmang C, Bieligk S, Lee E, Huber P, Hughes R, Turnage R. Primary colonic lymphoma. J Surg Oncol. 2000;74:257-262. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Fan CW, Changchien CR, Wang JY, Chen JS, Hsu KC, Tang R, Chiang JM. Primary colorectal lymphoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1277-1282. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Saito T, Toyoda H, Yamaguchi M, Nakamura T, Nakamura S, Mukai K, Fuke H, Wakita Y, Iwata M, Adachi Y. Ileocolonic lymphomas: a series of 16 cases. Endoscopy. 2005;37:466-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Armitage JO, Weisenburger DD. New approach to classifying non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas: clinical features of the major histologic subtypes. Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Classification Project. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2780-2795. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Radaszkiewicz T, Dragosics B, Bauer P. Gastrointestinal malignant lymphomas of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue: factors relevant to prognosis. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1628-1638. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Rosado MF, Byrne GE, Ding F, Fields KA, Ruiz P, Dubovy SR, Walker GR, Markoe A, Lossos IS. Ocular adnexal lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of a large cohort of patients with no evidence for an association with Chlamydia psittaci. Blood. 2006;107:467-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 10. | Iwamoto FM, DeAngelis LM, Abrey LE. Primary dural lymphomas: a clinicopathologic study of treatment and outcome in eight patients. Neurology. 2006;66:1763-1765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tu PH, Giannini C, Judkins AR, Schwalb JM, Burack R, O’Neill BP, Yachnis AT, Burger PC, Scheithauer BW, Perry A. Clinicopathologic and genetic profile of intracranial marginal zone lymphoma: a primary low-grade CNS lymphoma that mimics meningioma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5718-5727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zucca E, Conconi A, Pedrinis E, Cortelazzo S, Motta T, Gospodarowicz MK, Patterson BJ, Ferreri AJ, Ponzoni M, Devizzi L. Nongastric marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Blood. 2003;101:2489-2495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in RCA: 360] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ikeda J, Morii E, Yamauchi A, Kohara M, Hashimoto N, Yoshikawa H, Iwasaki M, Aozasa K. Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type developing in gonarthritis deformans. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4310-4312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Servitje O, Gallardo F, Estrach T, Pujol RM, Blanco A, Fernández-Sevilla A, Pétriz L, Peyrí J, Romagosa V. Primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma: a clinical, histopathological, immunophenotypic and molecular genetic study of 22 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1147-1158. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Welsh JS, Howard A, Hong HY, Lucas D, Ho T, Reding DJ. Synchronous bilateral breast mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas addressed with primary radiation therapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 2006;29:634-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Troch M, Formanek M, Streubel B, Müllauer L, Chott A, Raderer M. Clinicopathological aspects of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma of the parotid gland: a retrospective single-center analysis of 28 cases. Head Neck. 2011;33:763-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Koss MN. Pulmonary lymphoid disorders. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1995;12:158-171. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Shimura T, Kuwano H, Kashiwabara K, Kojima M, Masuda N, Suzuki H, Kanoh K, Saitoh T, Asao T. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the extrahepatic bile duct. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:360-362. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Lugton I. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues as sites for uptake, carriage and excretion of tubercle bacilli and other pathogenic mycobacteria. Immunol Cell Biol. 1999;77:364-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Thieblemont C, Bastion Y, Berger F, Rieux C, Salles G, Dumontet C, Felman P, Coiffier B. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue gastrointestinal and nongastrointestinal lymphoma behavior: analysis of 108 patients. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1624-1630. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Hahn JS, Kim YS, Lee YC, Yang WI, Lee SY, Suh CO. Eleven-year experience of low grade lymphoma in Korea (based on REAL classification). Yonsei Med J. 2003;44:757-770. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Kim MH, Jung JT, Kim EJ, Kim TW, Kim SY, Kwon JG, Kim EY, Sung WJ. A case of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the sigmoid colon presenting as a semipedunculated polyp. Clin Endosc. 2014;47:192-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Akasaka R, Chiba T, Dutta AK, Toya Y, Mizutani T, Shozushima T, Abe K, Kamei M, Kasugai S, Shibata S. Colonic mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2012;6:569-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nathwani BN, Anderson JR, Armitage JO, Cavalli F, Diebold J, Drachenberg MR, Harris NL, MacLennan KA, Müller-Hermelink HK, Ullrich FA. Marginal zone B-cell lymphoma: A clinical comparison of nodal and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue types. Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Classification Project. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2486-2492. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Cyrany J, Pintér M, Tycová V, Krejsek J, Belada D, Rejchrt S, Bures J. Trimodality imaging of colonic lymphoma. Endoscopy. 2009;41 Suppl 2:E1-E2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Traverse-Glehen A, Felman P, Callet-Bauchu E, Gazzo S, Baseggio L, Bryon PA, Thieblemont C, Coiffier B, Salles G, Berger F. A clinicopathological study of nodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma. A report on 21 cases. Histopathology. 2006;48:162-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sipos F, Muzes G. Isolated lymphoid follicles in colon: switch points between inflammation and colorectal cancer? World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1666-1673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Toyomasu Y, Tsutsumi S, Yamaguchi S, Mochiki E, Asao T, Kuwano H. Laparoscopy-assisted ileocecal resection for mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the appendix: case report. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:1078-1081. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Izumi T, Ozawa K. [Clinical staging classification of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma]. Nihon Rinsho. 2000;58:598-601. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Lalitha N. Clinical staging of adult non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Oncology. 1990;47:327-333. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Ho L, Davis RE, Conne B, Chappuis R, Berczy M, Mhawech P, Staudt LM, Schwaller J. MALT1 and the API2-MALT1 fusion act between CD40 and IKK and confer NF-kappa B-dependent proliferative advantage and resistance against FAS-induced cell death in B cells. Blood. 2005;105:2891-2899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Novak U, Basso K, Pasqualucci L, Dalla-Favera R, Bhagat G. Genomic analysis of non-splenic marginal zone lymphomas (MZL) indicates similarities between nodal and extranodal MZL and supports their derivation from memory B-cells. Br J Haematol. 2011;155:362-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Libra M, Gloghini A, Malaponte G, Gangemi P, De Re V, Cacopardo B, Spandidos DA, Nicoletti F, Stivala F, Zignego AL. Association of t(14; 18) translocation with HCV infection in gastrointestinal MALT lymphomas. J Hepatol. 2008;49:170-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Ambrosetti A, Zanotti R, Pattaro C, Lenzi L, Chilosi M, Caramaschi P, Arcaini L, Pasini F, Biasi D, Orlandi E. Most cases of primary salivary mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma are associated either with Sjoegren syndrome or hepatitis C virus infection. Br J Haematol. 2004;126:43-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Nocturne G, Boudaoud S, Miceli-Richard C, Viengchareun S, Lazure T, Nititham J, Taylor KE, Ma A, Busato F, Melki J. Germline and somatic genetic variations of TNFAIP3 in lymphoma complicating primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Blood. 2013;122:4068-4076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Smedby KE, Hjalgrim H, Askling J, Chang ET, Gregersen H, Porwit-MacDonald A, Sundström C, Akerman M, Melbye M, Glimelius B. Autoimmune and chronic inflammatory disorders and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma by subtype. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:51-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 280] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 37. | Tursi A, Inchingolo CD. Synchronous gastric and colonic MALT-lymphoma in coeliac disease: a long-term follow-up on gluten-free diet. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:1035-1038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | García-Sánchez MV, Poyato-González A, Giráldez-Jiménez MD, Gómez-Camacho F, Espigares del Aguila A, de Dios-Vega JF. [MALT lymphoma in a patient with Crohn’s disease. A causal or incidental association?]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;29:74-76. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Mangla V, Pal S, Dash NR, Das P, Ahuja V, Sharma A, Sahni P, Chattopadhyay TK. Rectal MALT lymphoma associated with ulcerative colitis. Trop Gastroenterol. 2012;33:225-228. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Al-Saleem T, Al-Mondhiry H. Immunoproliferative small intestinal disease (IPSID): a model for mature B-cell neoplasms. Blood. 2005;105:2274-2280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Goodlad JR, Davidson MM, Hollowood K, Ling C, MacKenzie C, Christie I, Batstone PJ, Ho-Yen DO. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma and Borrelia burgdorferi infection in patients from the Highlands of Scotland. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1279-1285. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Husain A, Roberts D, Pro B, McLaughlin P, Esmaeli B. Meta-analyses of the association between Chlamydia psittaci and ocular adnexal lymphoma and the response of ocular adnexal lymphoma to antibiotics. Cancer. 2007;110:809-815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Stolte M, Bayerdörffer E, Morgner A, Alpen B, Wündisch T, Thiede C, Neubauer A. Helicobacter and gastric MALT lymphoma. Gut. 2002;50 Suppl 3:III19-III24. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Psyrri A, Papageorgiou S, Economopoulos T. Primary extranodal lymphomas of stomach: clinical presentation, diagnostic pitfalls and management. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1992-1999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Avilés A, Nambo MJ, Neri N, Huerta-Guzmán J, Cuadra I, Alvarado I, Castañeda C, Fernández R, González M. The role of surgery in primary gastric lymphoma: results of a controlled clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2004;240:44-50. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Yoon SS, Coit DG, Portlock CS, Karpeh MS. The diminishing role of surgery in the treatment of gastric lymphoma. Ann Surg. 2004;240:28-37. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Takada M, Ichihara T, Fukumoto S, Nomura H, Kuroda Y. Laparoscopy-assisted colon resection for mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma in the cecum. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1003-1005. [PubMed] |

| 48. | Aguiar-Bujanda D, Llorca-Mártinez I, Rivero-Vera JC, Blanco-Sánchez MJ, Jiménez-Gallego P, Mori-De Santiago M, Limeres-Gonzalez MA, Cabrera-Marrero JC, Hernández-Sosa M, Galván-Ruíz S. Treatment of gastric marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisone. Hematol Oncol. 2014;32:139-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Curcio A, Bertelli R, Gentilini P, Ronconi S, Saragoni L, Vagliasindi A, Mura G, Mazza P, Framarini M, Verdecchia GM. [Multimodal treatment of gastric MALT lymphoma: our experience]. Suppl Tumori. 2005;4:S77-S78. [PubMed] |

| 50. | d’Amore F, Brincker H, Grønbaek K, Thorling K, Pedersen M, Jensen MK, Andersen E, Pedersen NT, Mortensen LS. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a population-based analysis of incidence, geographic distribution, clinicopathologic presentation features, and prognosis. Danish Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:1673-1684. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Arcaini L, Paulli M, Burcheri S, Rossi A, Spina M, Passamonti F, Lucioni M, Motta T, Canzonieri V, Montanari M. Primary nodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma: clinical features and prognostic assessment of a rare disease. Br J Haematol. 2007;136:301-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Nathwani BN, Drachenberg MR, Hernandez AM, Levine AM, Sheibani K. Nodal monocytoid B-cell lymphoma (nodal marginal-zone B-cell lymphoma). Semin Hematol. 1999;36:128-138. [PubMed] |

P- Reviewer: Skok P S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: AmEditor E- Editor: Zhang DN