Published online Dec 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17525

Revised: June 26, 2014

Accepted: July 29, 2014

Published online: December 14, 2014

Processing time: 213 Days and 21.7 Hours

AIM: To determine the clinical, epidemiological and phenotypic characteristics of ulcerative colitis (UC) in Saudi Arabia by studying the largest cohort of Arab UC patients.

METHODS: Data from UC patients attending gastroenterology clinics in four tertiary care centers in three cities between September 2009 and September 2013 were entered into a validated web-based registry, inflammatory bowel disease information system (IBDIS). The IBDIS database covers numerous aspects of inflammatory bowel disease. Patient characteristics, disease phenotype and behavior, age at diagnosis, course of the disease, and extraintestinal manifestations were recorded.

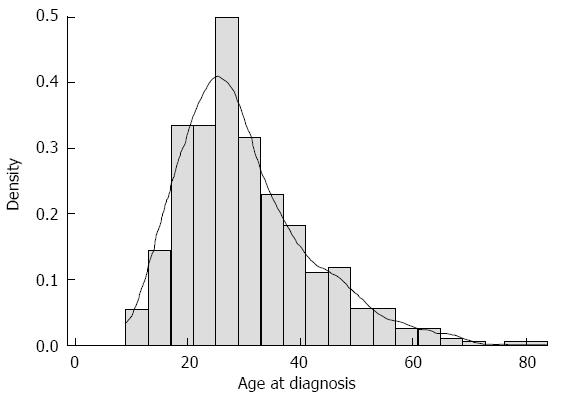

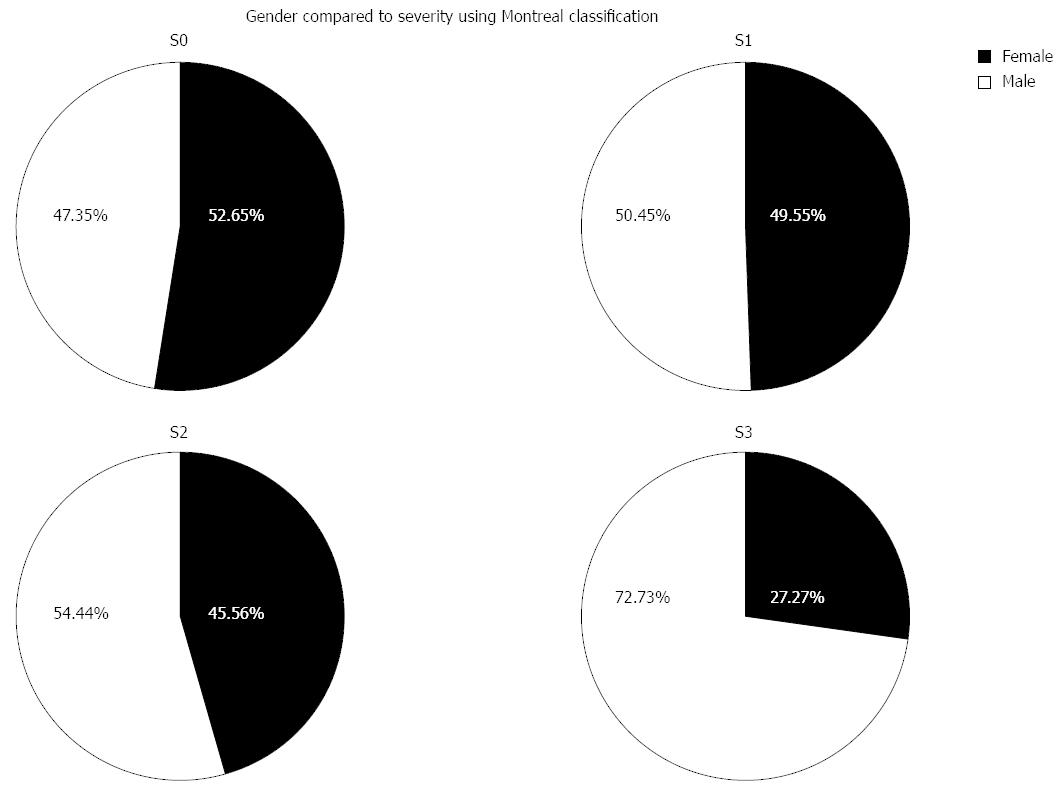

RESULTS: Among 394 UC patients, males comprised 51.0% and females 49.0%. According to the Montréal classification of age, the major chunk of our patients belonged to the A2 category for age of diagnosis at 17-40 years (68.4%), while 24.2% belonged to the A3 category for age of diagnosis at > 40 years. According to the same classification, a majority of patients had extensive UC (42.7%), 35.3% had left-sided colitis and 29.2% had only proctitis. Moreover, 51.3% were in remission, 16.6% had mild UC, 23.4% had moderate UC and 8.6% had severe UC. Frequent relapse occurred in 17.4% patients, infrequent relapse in 77% and 4.8% had chronic disease. A majority (85.2%) of patients was steroid responsive. With regard to extraintestinal manifestations, arthritis was present in 16.4%, osteopenia in 31.4%, osteoporosis in 17.1% and cutaneous involvement in 7.0%.

CONCLUSION: The majority of UC cases were young people (17-40 years), with a male preponderance. While the disease course was found to be similar to that reported in Western countries, more similarities were found with Asian countries with regards to the extent of the disease and response to steroid therapy.

Core tip: Despite several reports suggesting an increase in the incidence of ulcerative colitis (UC) among Arabs in recent years, there is insufficient information about it, particularly in Saudi Arabia. Our aim was to determine the clinical, epidemiological and phenotypic characteristics of UC in Saudi Arabia by studying the largest cohort of Arab UC patients. We found that UC has a relatively higher incidence in Saudi Arabia and the majority of UC cases are diagnosed in young people (17-40 years), with a male preponderance.

- Citation: Alharbi OR, Azzam NA, Almalki AS, Almadi MA, Alswat KA, Sadaf N, Aljebreen AM. Clinical epidemiology of ulcerative colitis in Arabs based on the Montréal classification. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(46): 17525-17531

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i46/17525.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17525

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), the etiology of which remains relatively unclear. Studying the epidemiology of IBD is crucial for understanding the public health burden it poses and for planning appropriate health programs for individuals with IBD[1,2]. Comprehensive descriptive epidemiological studies can offer clues about the causes of this disease[3,4].

The prevalence of IBD varies greatly worldwide and Western European and North American countries are traditionally considered as the high incidence areas[3,5,6]. Previously, UC was considered to be rare in developing countries but recently a surge in its incidence has been observed in populations in which it was earlier thought to be non-existent, e.g., Chinese populations in Hong Kong and Singapore and Arab nations[4,7-9].

Although the evidence is insufficient, there are reports of the growing incidence of UC in the Middle East[7-9]. Recently, the incidence in the Arab population was reported to be 22/100000[10-13]. Moreover, a recent retrospective study in Saudi Arabia reported an increase in the number of UC patients who were referred to tertiary care centers[14]. Another retrospective study on Libyan children showed that the incidence of IBD was increasing and the clinical features were similar to those reported in other countries[15]. Despite the reports of the increase in the incidence of UC among Arabs in recent years, there is limited data about the characteristics of these patients and the disease course in Saudi Arabia[16,17]. The aim of this study, therefore, was to determine the clinical, epidemiological and phenotypic characteristics of UC in Saudi Arabia based on patient data recorded regularly in the IBD registry.

Since September 2009, the inflammatory bowel disease information system (IBDIS)[18] has been used to register IBD patients. Initially, it contained data for patients at only one tertiary care center (King Khalid University Hospital); however, four other centers, including three private care centers in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, were added shortly thereafter. IBDIS (http://www.ibdis.net) is a web-based documentation system comprised of nine blocks covering numerous aspects of IBD-related parameters, including demographics, diagnosis, age at diagnosis according to the Montréal classification system, course of the disease, extraintestinal manifestations, complications, risk factors, surgical and conservative therapy. All of these parameters in our study population were recorded in the registry.

UC patients presenting to gastroenterology clinics or endoscopy units between September 2009 and September 2013 were interviewed using their clinical charts and screened by the attending physician and a trained research assistant; the required information was documented and directly incorporated into the registry. Patient data was updated on a regular basis on every follow-up visit to the gastroenterology clinics. Given the inconsistency with which features based on the Montréal classification are generally reported[19], 10% of the data in the registry was randomly checked and validated by the investigators.

The Montréal classification was used to classify the extent of UC (ulcerative proctitis, E1; left-sided UC, E2; extensive UC, E3) and disease severity (UC in clinical remission, S0; mild UC, S1; moderate UC, S2; severe UC, S3)[20]. The extent (E) and severity (S) of the disease were considered cumulatively up to the time of the most recent endoscopic, histopathological, radiological and other clinical investigations and surgical notes.

The course of the disease was assessed at the first time of inclusion in the registry: infrequent relapse, ≤ 1 relapse per year; frequent relapse, > 1 relapse per year; chronic disease, no remission throughout a 1 year period. Changes in the disease course during follow-up were also registered.

Age of onset as per the Montreal classification was reported and categorized as A1 for those with age of diagnosis at 16 years or younger, A2 and A3 for age of diagnosis at 17-40 years and > 40 years, respectively. Osteopenia was defined when T-score was between -1 and -2.5 SD and osteoporosis when T-score < -2.5 SD.

The diagnosis of UC (based on standard clinical, endoscopic, radiological and histological criteria) was reviewed thoroughly using the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization guidelines[11]. Only UC patients who had undergone a full colonoscopy with terminal ileum intubation and biopsy (in the absence of stenosis) were included.

If clinically indicated, computed tomography enterography (CTE) or magnetic resonance imaging enterography were performed to exclude Crohn’s disease.

Continuous variables were represented as means, standard deviations and minimum and maximum values, and categorical variables as frequencies. 95%CI was estimated for all variables. We used STATA 11.2 (StataCorp, Texas, United States) for our analyses. A P-value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. No attempt at imputation was made for missing data.

All patients gave their informed consent for participation in this study. The study was approved by the institutional review board of King Khalid University Hospital and site-specific approval was obtained from each participating hospital.

Among 394 UC patients, 94.0% were of Saudi nationality and the rest were non-Saudis. Moreover, 8.3% (95%CI: 5.4-11.2) of the patients lived in rural areas and the remainder lived in urban areas. The mean age at diagnosis was 30.2 (mean) ± 0.6 (SD) years, with a mean duration of 8 years (95%CI: 7.3-8.5), and 51% (95%CI: 46.0-56.0) were males and 49% (95%CI: 44.0-54.0) females (Table 1).

| Variables | (n = 394) | 95%CI |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 51% | 46-56 |

| Female | 49% | 44-54 |

| Nationality | ||

| Saudi | 94% | 91-96 |

| Non-Saudi | 6% | 3.7-8.4 |

| Environment | ||

| Urban | 91.6% | 88.7-94.5 |

| Rural | 8.3% | 5.4-11.2 |

| Mean BMI | 22.6 | 22.5-22.7 |

| Mean age (yr) | 30.1 | 28.9-31.4 |

| Mean duration of disease (yr) | 8 | 7.3-8.5 |

| Smoking | ||

| Smokers | 7.8% | 4.9-10.7 |

| Non-Smokers | 92.2% | 89.2-95.1 |

| Course | ||

| Infrequent | 77.5% | 73.2-82.2 |

| Frequent | 17.3% | 13.3-21.5 |

| Chronic | 4.8% | 2.4-7.1 |

| Steroid use | ||

| Once | 33.5% | 28.7-39.1 |

| Twice | 10.8% | 7.4-14.3 |

| Three | 8.3% | 5.3-11.4 |

| More than three times | 8.6% | 5.6-11.8 |

| Never | 37.5% | 32.6-43.3 |

| Number of relatives with CD | ||

| First degree | 0.6% | 0.2-1.5 |

| Second degree | 0.6% | 0.2-1.5 |

| Number of relatives with UC | ||

| First degree | 7% | 3.3-10.7 |

| Second degree | 1.8% | 0.4-3.3 |

| Number of relatives with IBDU | ||

| First degree | 0.6% | 0.2-1.5 |

| Second degree | 0.3% | 0.3-0.9 |

| Number of relatives with colorectal cancer | ||

| First degree | 0.9% | 0.1-2.0 |

| Second degree | 0.9% | 0.1-2.0 |

According to the Montréal classification system, the majority (68.4%) of our patients with disease were A2 (17.0-40.0 years) (Figure 1, Table 2). Extensive UC was present in 42.7% (95%CI: 37.3-48.1) according to the Montréal classification, while left-sided colitis was found in 35.3% (95%CI: 30.0-40.0) and proctitis was found in 22% (95%CI: 17.5-26.5). In 51.3% (95%CI: 46.0-56.8) of the patients the disease was in remission, mild UC was found in 16.6% (95%CI: 12.5-20.7), moderate UC, 23.4% (95%CI: 18.8-28.0) and severe UC occurred in 8.6% (95%CI: 5.5-11.6), with a male predominance (Figure 2). There was no significant difference in disease extent between different age groups.

| Variables | n = 394 | 95%CI |

| Age, Montréal classification | ||

| A1 | 7.3% | 4.7-9.9 |

| A2 | 68.4% | 63.8-73.0 |

| A3 | 24.2% | 20.0-28.4 |

| Extent, Montréal classification | ||

| E1 | 22.0% | 17.4-26.5 |

| E2 | 35.3 % | 30-40.5 |

| E3 | 42.7 % | 37.3-48.5 |

| Severity, Montréal classification | ||

| S0 | 51.4% | 46.0-57.0 |

| S1 | 16.6% | 12.5-20.6 |

| S2 | 23.4% | 18.75-28.0 |

| S3 | 8.6% | 5.5-11.6 |

Among our patients, 77.5% (95%CI: 73.2-82.2) had infrequent relapse, 17.3% (95%CI: 13.3-21.5) had frequent relapse and 4.8% (95%CI: 2.4-7.1) had chronic disease with no remission.

During the disease course, the majority of patients were treated with 5-ASA: 54.7% used the oral form, 7.3% topical, and 38.0% a combination of both. Moreover, 37.5% of our patients had never used systemic steroids, 33.5% had used it only once, and 8.6% had used it more than three times. Additionally, 85.2% (95%CI: 78.9-91.4) were steroid responsive, 7.0% (95%CI: 2.5-11.5) were steroid dependent, and 6.2% (95%CI: 2.0-10.5) did not respond to steroid treatment. In particular, patients with extensive colitis (E3) were more likely to have been treated with multiple courses of steroids. Immunomodulators were used in 69 patients; most were treated with azathioprine (97.1%). Anti-TNF drugs were used as maintenance therapy in 33 patients (8.3%). Proctocolectomy was performed on 23 (5.8%) patients; it was performed after the detection for dysplasia and cancer in 11 of these patients and the rest were treated after failure of medical therapy.

With regards to extraintestinal manifestations, arthritis was present in 17.5% (95%CI: 10.4-24.5) of the patients, osteopenia in 30.5% (95%CI: 21.5-39.4) and osteoporosis in 17.1% (95%CI: 9.8-24.4). Primary sclerosing cholangitis was found in 0.9% of the patients and deep vein thrombosis was found in 1.9%, one of whom had a fatal pulmonary embolism during hospitalization. Cutaneous involvement was observed in 7.06% of our population; the majority of these patients had an unspecific skin rash, while 23.8% had erythema nodosum (Table 3).

| Variables | n = 312 | 95%CI |

| PSC | 0.9% | 0.01-2.0 |

| Venous thrombosis | 1.9% | 0.3-3.3 |

| Eye manifestation | 1.5% | 0.1-2.9 |

| Stomatitis | 1.5% | 0.1-2.9 |

| Joint involvement | 17.5% | 10.4-24.5 |

| Bone manifestation | ||

| Osteoporosis | 17.1% | 9.8-24.4 |

| Osteopenia | 30.5% | 21.5-39.4 |

| Skin manifestation | 7.06% | 4.2-9.8 |

| Erythema nodosum | 23.8% | 3.9-43 |

| Pyoderma gangraenosum | 4.8% | 0.1-14 |

| Psoriasis | 9.5% | 0.1-23.4 |

| Others | 61.9% | 39.2-84.5 |

This study is the largest and most comprehensive epidemiological study on UC in an Arab population, incorporating 394 UC patients by using data from a validated database web system. We found a slight male predominance, which is consistent with previous studies from Saudi Arabia[13,19,20] and other Arab populations in Kuwait[21] and Lebanon[22]. This finding is also similar to those carried out on a Turkish population[23], South Asians in the United Kingdom[24] and North American populations[25]. On the contrary, studies from Iran[26] and Sri Lanka[27] have shown a female predominance, while studies in Japan[28] and Korea[29] and other Asian countries[30] have shown a similar incidence in males and females.

In our series, extensive colitis was more common than left-sided colitis and proctitis. Similar findings were observed in other Arabic countries, specifically Lebanon[22] and Kuwait[21], and in western African, American and Hispanic populations[31] and in Iran[32]. However, in other Asian countries such as Korea[29], and Japan[33], proctitis was more common, while in China[34], Singapore[35] and Sir Lanka[27], left-sided colitis was more common. The differences could be attributed to the study settings because hospital-based studies are more likely to have a higher proportion of extensive colitis patients than population-based studies as these patients need more advanced care and cannot be managed in primary care clinics.

The rate of osteoporosis and osteopenia in our population were similar to those reported in other studies from Saudi Arabia[36], the United States[37] and Italy[38]. In contrast, a lower prevalence of osteoporosis was reported from Iran[39] and Norway[40] and a recent large retrospective database analysis in North America found a lower prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis in UC patients[41]. However, the latter study included only male patients, only 30% of whom were treated with steroids, compared to 62.5% in our study. Therefore, the difference could be attributed to the inclusion of only males and the lower percentage of patients who were treated with steroids. Moreover, we think that the higher prevalence of osteoporosis and osteopenia in our population may be related to the high incidence of Vitamin D deficiency in Saudi Arabia rather than UC itself[42]. In comparison with Western populations[43], our population had a higher rate of peripheral arthritis. However, our results are similar to those of two other studies from Arabic populations in Saudi Arabia[13] and Kuwait[44] and from studies in Korea[45] and Hungary[46].

With regards to steroid therapy, 37.5% of our patients never used systemic steroids, which is similar to the finding in a 5 year follow-up study on UC patients in the United Kingdom[47]. In the same study, 82% of the patients had a complete or partial response to steroids and 18% showed no response; these findings are also similar to those in our population (85.5% responded, 7.0% were steroid dependent, and 6.2% did not respond to steroid treatment). Similar findings were reported in a population-based study in Olmsted County, United States[48].

Although this is not a population-based study, a major advantage of this cross-sectional prospective study is that it was conducted on the largest cohort of Arab UC patients from four centers in an area that was, until recently, not known to have a surge in the incidence of IBD.

In conclusion, the prevalence of UC seems to be increasing in Saudi Arabia and the majority of UC cases are diagnosed in young people (17-40 years), with a male preponderance. While the disease course was found to be similar to that reported in Western countries, more similarities were found with Asian countries with regards to the extent of the disease and response to steroid therapy.

The authors would like to extend their sincere appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University.

Despite several reports suggesting an increase in the incidence of ulcerative colitis (UC) among Arabs in recent years, there is insufficient information about it, particularly in Saudi Arabia. This study is an effort to relay information regarding epidemiology of this particular disease.

More studies are required to understand this surge in the incidence of ulcerative colitis and whether infectious or environmental factors are the reason.

UC is an emerging disease with a clear surge in the incidence in recent years. We tried to determine the clinical, epidemiological and phenotypic characteristics of UC in Saudi Arabia by studying the largest cohort of Arab UC patients.

The classical definition of ulcerative colitis is a macroscopic and microscopic continuous mucosal inflammation without histological evidence of granulomas. The disease affects at least the rectum and may spread to a varying extent but continuously in the oral direction, up to the maximal form of ulcerative pancolitis (endoscopy). Exceptions from classical ulcerative colitis are the “rectal sparing colitis” and any form of the disease that occurs in conjunction with focal periappendicular involvement, which is separated from the inflamed portion by normal mucosa.

This paper addresses the clinical, epidemiological and phenotypic characteristics of UC in Saudi Arabia by studying the largest cohort of Arab UC patients and concluded that prevalence of UC seems to be increasing in Saudi Arabia and that the majority of UC cases are diagnosed in young people (17-40 years), with a male preponderance. The authors also pointed out that while the disease course was found to be similar to that reported in Western countries, more similarities were found with Asian countries with regards to the extent of the disease and response to steroid therapy.

| 1. | Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Rawsthorne P, Wajda A. Epidemiology of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in a central Canadian province: a population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:916-924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 493] [Cited by in RCA: 511] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hay JW, Hay AR. Inflammatory bowel disease: costs-of-illness. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;14:309-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bernstein CN, Wajda A, Svenson LW, MacKenzie A, Koehoorn M, Jackson M, Fedorak R, Israel D, Blanchard JF. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1559-1568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 402] [Cited by in RCA: 451] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jussila A, Virta LJ, Kautiainen H, Rekiaro M, Nieminen U, Färkkilä MA. Increasing incidence of inflammatory bowel diseases between 2000 and 2007: a nationwide register study in Finland. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:555-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Solberg IC, Lygren I, Jahnsen J, Aadland E, Høie O, Cvancarova M, Bernklev T, Henriksen M, Sauar J, Vatn MH. Clinical course during the first 10 years of ulcerative colitis: results from a population-based inception cohort (IBSEN Study). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:431-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 498] [Cited by in RCA: 555] [Article Influence: 32.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Henriksen M, Jahnsen J, Lygren I, Vatn MH, Moum B. Are there any differences in phenotype or disease course between familial and sporadic cases of inflammatory bowel disease? Results of a population-based follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1955-1963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Siddique I, Alazmi W, Al-Ali J, Al-Fadli A, Alateeqi N, Memon A, Hasan F. Clinical epidemiology of Crohn’s disease in Arabs based on the Montreal Classification. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1689-1697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Abdul-Baki H, ElHajj I, El-Zahabi LM, Azar C, Aoun E, Zantout H, Nasreddine W, Ayyach B, Mourad FH, Soweid A. Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Lebanon. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:475-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Aghazadeh R, Zali MR, Bahari A, Amin K, Ghahghaie F, Firouzi F. Inflammatory bowel disease in Iran: a review of 457 cases. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1691-1695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | El Mouzan MI, Abdullah AM, Al Habbal MT. Epidemiology of juvenile-onset inflammatory bowel disease in central Saudi Arabia. J Trop Pediatr. 2006;52:69-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lennard-Jones JE. Classification of inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1989;170:2-6; discussion 16-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1396] [Cited by in RCA: 1459] [Article Influence: 39.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Khan HA, Mahrous AS, Fachartz FI. Ulcerative colitis amongst the Saudis: six-year experience from Al-Madinah region. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 1996;2:69-73. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Contractor QQ, Contractor TQ, Ul Haque I, El Mahdi el Mel B. Ulcerative colitis: Al-Gassim experience. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:22-27. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Alamin AH, Ayoola EA, El Boshra AS, Hamaza MK, Gupta V, Ahmed MA. Ulcerative colitis in Saudi Arabia: a retrospective analysis of 33 cases treated in a regional referral hospital in Gizan. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:55-58. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Ahmaida A, Al-Shaikhi S. Childhood Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Libya: Epidemiological and Clinical features. Libyan J Med. 2009;4:70-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Fadda MA, Peedikayil MC, Kagevi I, Kahtani KA, Ben AA, Al HI, Sohaibani FA, Quaiz MA, Abdulla M, Khan MQ. Inflammatory bowel disease in Saudi Arabia: a hospital-based clinical study of 312 patients. Ann Saudi Med. 2012;32:276-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 17. | El Mouzan MI, Al Mofarreh MA, Assiri AM, Hamid YH, Al Jebreen AM, Azzam NA. Presenting features of childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease in the central region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2012;33:423-428. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Oefferlbauer A, Miehsler W, Eckmuellner O, Gangl A, Vogelsang H, Reinisch W. Interobserver agreement analysis of a National Inflammatory Bowel Disease Information System (IBDIS). Gastroenterology. 2003;124:A507. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Krishnaprasad K, Andrews JM, Lawrance IC, Florin T, Gearry RB, Leong RW, Mahy G, Bampton P, Prosser R, Leach P. Inter-observer agreement for Crohn’s disease sub-phenotypes using the Montreal Classification: How good are we? A multi-centre Australasian study. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:287-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR, Caprilli R, Colombel JF, Gasche C, Geboes K. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19 Suppl A:5A-36A. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Al-Shamali MA, Kalaoui M, Patty I, Hasan F, Khajah A, Al-Nakib B. Ulcerative colitis in Kuwait: a review of 90 cases. Digestion. 2003;67:218-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Abdul-Baki H, Hashash JG, Elhajj II, Azar C, El Zahabi L, Mourad FH, Barada KA, Sharara AI. A randomized, controlled, double-blind trial of the adjunct use of tegaserod in whole-dose or split-dose polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution for colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:294-300; quiz 334, 336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ozin Y, Kilic MZ, Nadir I, Cakal B, Disibeyaz S, Arhan M, Dagli U, Tunc B, Ulker A, Sahin B. Clinical features of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in Turkey. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2009;18:157-162. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Walker DG, Williams HR, Kane SP, Mawdsley JE, Arnold J, McNeil I, Thomas HJ, Teare JP, Hart AL, Pitcher MC. Differences in inflammatory bowel disease phenotype between South Asians and Northern Europeans living in North West London, UK. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1281-1289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Loftus EV, Silverstein MD, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR. Ulcerative colitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940-1993: incidence, prevalence, and survival. Gut. 2000;46:336-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 360] [Cited by in RCA: 360] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Safarpour AR, Hosseini SV, Mehrabani D. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel diseases in iran and Asia; a mini review. Iran J Med Sci. 2013;38:140-149. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Subasinghe D, Nawarathna NM, Samarasekera DN. Disease characteristics of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): findings from a tertiary care centre in South Asia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1562-1567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yoshida Y, Murata Y. Inflammatory bowel disease in Japan: studies of epidemiology and etiopathogenesis. Med Clin North Am. 1990;74:67-90. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Yang SK, Hong WS, Min YI, Kim HY, Yoo JY, Rhee PL, Rhee JC, Chang DK, Song IS, Jung SA. Incidence and prevalence of ulcerative colitis in the Songpa-Kangdong District, Seoul, Korea, 1986-1997. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:1037-1042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ng SC, Tang W, Ching JY, Wong M, Chow CM, Hui AJ, Wong TC, Leung VK, Tsang SW, Yu HH. Incidence and phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease based on results from the Asia-pacific Crohn’s and colitis epidemiology study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:158-165.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 515] [Cited by in RCA: 615] [Article Influence: 47.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 31. | Nguyen GC, Torres EA, Regueiro M, Bromfield G, Bitton A, Stempak J, Dassopoulos T, Schumm P, Gregory FJ, Griffiths AM. Inflammatory bowel disease characteristics among African Americans, Hispanics, and non-Hispanic Whites: characterization of a large North American cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1012-1023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Shayesteh AA, Saberifirozi M, Abedian S, Sebghatolahi V. Epidemiological, Demographic, and Colonic Extension ofUlcerative Colitis in Iran: A Systematic Review. Middle East J Dig Dis. 2013;5:29-36. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Fujimoto T, Kato J, Nasu J, Kuriyama M, Okada H, Yamamoto H, Mizuno M, Shiratori Y. Change of clinical characteristics of ulcerative colitis in Japan: analysis of 844 hospital-based patients from 1981 to 2000. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:229-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Jiang Y, Xia B, Jiang L, Lv M, Guo Q, Chen M, Li J, Xia HH, Wong BC. Association of CTLA-4 gene microsatellite polymorphism with ulcerative colitis in Chinese patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:369-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Ling KL, Ooi CJ, Luman W, Cheong WK, Choen FS, Ng HS. Clinical characteristics of ulcerative colitis in Singapore, a multiracial city-state. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:144-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Ismail MH, Al-Elq AH, Al-Jarodi ME, Azzam NA, Aljebreen AM, Al-Momen SA, Bseiso BF, Al-Mulhim FA, Alquorain A. Frequency of low bone mineral density in Saudi patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:201-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Etzel JP, Larson MF, Anawalt BD, Collins J, Dominitz JA. Assessment and management of low bone density in inflammatory bowel disease and performance of professional society guidelines. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:2122-2129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Ardizzone S, Bollani S, Bettica P, Bevilacqua M, Molteni P, Bianchi Porro G. Altered bone metabolism in inflammatory bowel disease: there is a difference between Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. J Intern Med. 2000;247:63-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Zali M, Bahari A, Firouzi F, Daryani NE, Aghazadeh R, Emam MM, Rezaie A, Shalmani HM, Naderi N, Maleki B. Bone mineral density in Iranian patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:758-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Jahnsen J, Falch JA, Mowinckel P, Aadland E. Vitamin D status, parathyroid hormone and bone mineral density in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:192-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Khan N, Abbas AM, Almukhtar RM, Khan A. Prevalence and predictors of low bone mineral density in males with ulcerative colitis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:2368-2375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Sadat-Ali M, Al Elq AH, Al-Turki HA, Al-Mulhim FA, Al-Ali AK. Influence of vitamin D levels on bone mineral density and osteoporosis. Ann Saudi Med. 2011;31:602-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Orchard TR, Wordsworth BP, Jewell DP. Peripheral arthropathies in inflammatory bowel disease: their articular distribution and natural history. Gut. 1998;42:387-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 355] [Cited by in RCA: 329] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Al-Jarallah K, Shehab D, Al-Azmi W, Al-Fadli A. Rheumatic complications of inflammatory bowel disease among Arabs: a hospital-based study in Kuwait. Int J Rheum Dis. 2013;16:134-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Suh CH, Lee CH, Lee J, Song CH, Lee CW, Kim WH, Lee SK. Arthritic manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. J Korean Med Sci. 1998;13:39-43. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Lakatos L, Pandur T, David G, Balogh Z, Kuronya P, Tollas A, Lakatos PL. Association of extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease in a province of western Hungary with disease phenotype: results of a 25-year follow-up study. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2300-2307. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Ho GT, Chiam P, Drummond H, Loane J, Arnott ID, Satsangi J. The efficacy of corticosteroid therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: analysis of a 5-year UK inception cohort. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:319-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Faubion WA, Loftus EV, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. The natural history of corticosteroid therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:255-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 833] [Cited by in RCA: 801] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewer: Huang TY, Koch TR, Ozen H S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Zhang DN