Published online Oct 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i40.14696

Revised: April 3, 2014

Accepted: June 2, 2014

Published online: October 28, 2014

Processing time: 371 Days and 6.1 Hours

Chronic liver diseases with different aetiologies rely on the chronic activation of liver injuries which result in a fibrogenesis progression to the end stage of cirrhosis and liver failure. Based on the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms of a liver fibrosis, there has been proposed several kinds of approaches for the treatment of liver fibrosis. Recently, liver gene therapy has been developed as an alternative way to liver transplantation, which is the only effective therapy for chronic liver diseases. The activation of hepatic stellate cells, a subsequent release of inflammatory cytokines and an accumulation of extracellular matrix during the liver fibrogenesis are the major obstacles to the treatment of liver fibrosis. Several targeted strategies have been developed, such as antisense oligodeoxynucleotides, RNA interference and decoy oligodeoxynucleotides to overcome this barriers. With this report an overview will be provided of targeted strategies for the treatment of liver cirrhosis, and particularly, of the targeted gene therapy using short RNA and DNA segments.

Core tip: Recent advances in understanding the mechanisms underlying liver fibrogenesis, including regulation of inflammatory cytokine signaling, the dynamic process of hepatic stellate cell activation and extracellular matrix degradation. The only option for patients suffering from severe and late-stage cirrhosis is liver transplantation; however, it is limited by the number of available donor organs. Therefore, development of new therapeutic strategies for liver fibrosis and cirrhosis are needed. This review focuses on the recent advances relating to the therapeutic application of liver fibrogenesis through the modulation of gene expression.

- Citation: Kim KH, Park KK. Small RNA- and DNA-based gene therapy for the treatment of liver cirrhosis, where we are? World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(40): 14696-14705

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i40/14696.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i40.14696

Chronic liver diseases are characterized by reiteration of liver injuries due to an infection by viral agents (mainly hepatitis B and C viruses) or to metabolic toxin/drug-induced (alcohol being predominant) and autoimmune diseases[1]. In response to various insults, the hepatocyte damage will cause the release of cytokines and other soluble factors by Kupffer cells, which lead to an activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). HSCs have been considered as the primary hepatic cell type which is responsible for the excess deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) during the liver fibrosis[2-5]. Excessive production of ECM results in an imbalance between fibrogenesis and fibrolysis, and leads subsequently to a scar formation. As the scarring progresses from the bridging fibrosis to the formation of complete nodules, it results in an architectural distortion and leads ultimately to liver cirrhosis[6]. In many patients the cirrhosis can result in liver failure and leads to a high morbidity and mortality worldwide[7].

The activation of HSCs is the key factor in liver fibrosis. It is responsible for the excess deposition of ECM and the formation of scars[8,9]. Vitamin A storing quiescent HSCs, are located in the normal liver in the space of Disse in close contact with hepatocyte and sinusoidal endothelial cells. Responding to hepatic injuries, HSCs migrate to the wound-healing area and secret large amounts of ECM, which results in septa formation in the chronically damaged liver[10,11]. Activated HSCs become contractile and secrete a wide variety of ECM proteins and bioactive mediators, including the transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), the platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and the connective tissue growth factor (CTGF). In turn, the proliferation of HSCs and the synthesis of collagen will be accelerated. The TGF-β1 is the most fibrogenic cytokine and increases after the HSC activation. In activated HSCs, TGF-β1 induces a strong and consistent upregulation of the genes encoding for collagens and other ECM components. It also regulates the matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) expression and their inhibitors (tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase, TIMP), which modulate the inflammatory reactions by influencing the T cell functions[12-14].

Recent advances were done to understand the mechanisms of the underlying liver fibrogenesis, including the regulation of inflammatory cytokine signaling, the dynamic process of HSC activation and the ECM degradation[8,9]. From a treatment viewpoint, several approaches have successfully inhibited the liver fibrogenesis in animal models. However, the possibility to reverse an established fibrosis is an essential issue, because a fibrotic liver disease may not present clinically until an advanced or cirrhotic stage. Although current treatments target the inflammatory responses, those treatments are still limited to treat an advanced liver fibrosis. The only option for patients suffering from severe and late-stage cirrhosis is the liver transplantation. However, transplantation are limited by the number of available donor organs[15]. Therefore, a development of new therapeutic strategies for liver fibrosis and cirrhosis is needed. This review focuses on the latest advances to modulate gene expressions for the therapeutic application in the liver fibrosis.

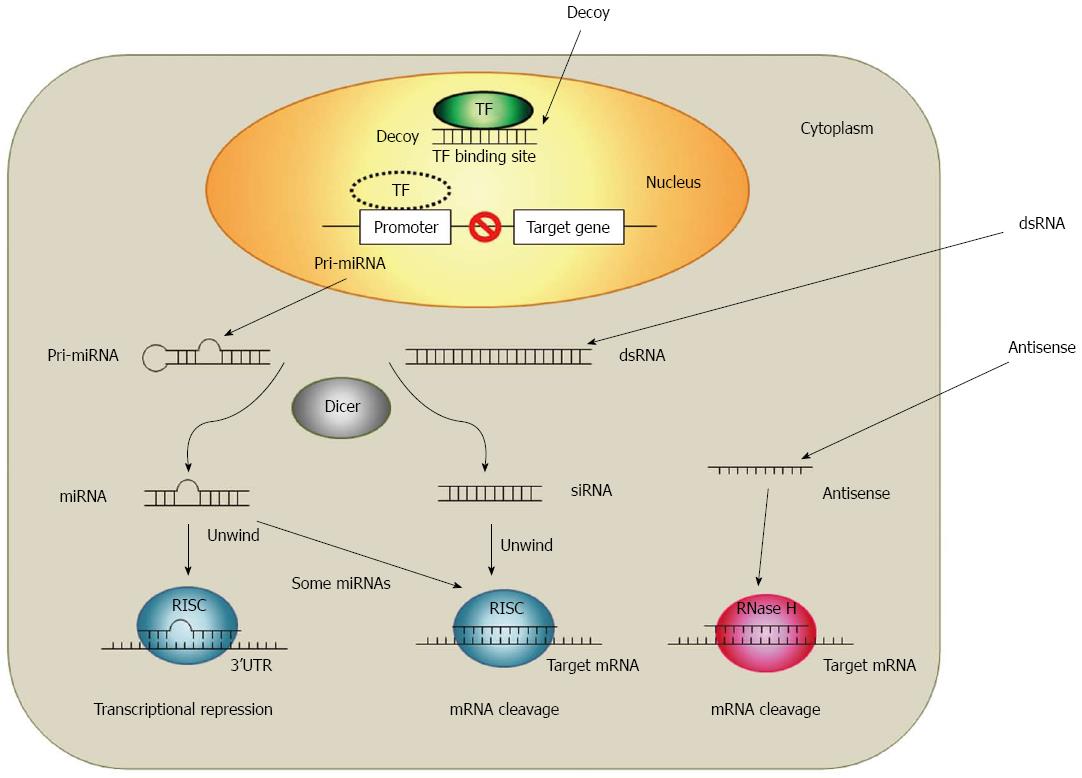

New techniques to inhibit target gene expressions based on a short RNA or DNA technology were provided due to recent progresses in the cellular and molecular research. Antisense oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs), small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs) and decoy ODNs are oligonucleotides which are able to modulate gene expressions. Although all of these four strategies use a short sequence of nucleotides (approximately 20 base pairs), each strategy differs in the nucleotide type (RNA or DNA) and in the number of strands (single or double stranded)[16]. The main difference between those four strategies is the way of their gene expression regulation. As shown in Figure 1, the decoy ODNs works at the pre-transcription level while siRNAs, miRNAs and antisense ODNs work at the post-translation level[17,18].

The development of antisense strategy started at the late 1970s after the discovery of the inhibition of a specific gene product expression due to short complementary DNA sequences[19-21]. Since then, the antisense strategy has become one of the most successful approaches for target validation and therapeutic purposes. Antisense ODNs are short chains of nucleic acids and consist usually of 10 to 30 nucleotides, which are typical single-stranded DNA or chemically modified DNA derivatives. Antisense ODNs specifically hybridize with their complementary targeted RNAs by Watson-Crick base-pairing[16]. RNA-antisense ODN heteroduplex activates ribonuclease H (RNase H)-cleavage of the target mRNA[22]. RNase H is a ubiquitous enzyme that hydrolyzes the RNA strand of an RNA-DNA duplex. The use in the gene therapy is the most widely discussed application of antisense strategy. The first antisense drug, VitraveneTM (Fomivirsen), was approved by the FDA for the treatment of cytomegalovirus-induced retinitis in AIDS patients[23]. Currently, there are about 30 clinical trials in various phases ongoing. Moreover, newer oligonucleotide chemistries are providing antisense molecules with higher binding affinities, greater stability and lower toxicity as clinical candidates[24-26].

RNA interference (RNAi) is the phenomenon in which siRNAs (21-23 nucleotide in length) silence targets gene by binding to its complimentary mRNA and triggers their elimination initially. It was discovered by Fire et al[27] in Caenorhabditis elegans. Like the antisense strategy, RNAi relies on the complementarity between RNA and its target mRNA. However, the mechanism of RNAi is slightly different to the antisense strategy. RNAi is a sequence-specific gene silencing mechanism which is evolutionarily conserved and induced by the exposure of double-stranded RNA(dsRNA)[28]. Long stretches of dsRNA can interact with the RNase III-like enzyme (DICER) to be cleaved into short (21-23 nucleotide) ds RNA with 3’ overhangs and produce what is known as siRNAs. Through the association with RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) these siRNAs are then unwound and associated with the complementary RNA. Those enzymes lead to a specific cleavage of complementary targets[29-32]. Inducers of the RNAi mechanism include endogenous miRNA, synthetic siRNA and the vector based short hairpin RNA (shRNA). RNAi-based therapies are intensively focused on gene therapies, and have potent knockdowns of targeted gene with a high sequence specificity[33].

Other classes where the RNAi mechanism is used are miRNAs. miRNAs control the translation of targeted mRNAs and act essentially as naturally occurring antisense ODN. miRNAs are endogenous, noncoding RNAi molecules about 22 nt long and are capable to negative modulate the post-transcriptional expression genes by binding to their complementary 3’ untranslated region (UTR) of mRNA targets[34]. miRNAs differ from siRNAs in their molecular origins and in their mode of target recognition. Unlike siRNAs, miRNAs are generated in the nucleus and transported to the cytoplasm as mature, hairpin structures[35]. In many cases, miRNAs bind to the target 3’ UTRs through imperfect complementarity at multiple sites, while siRNAs often form a perfect duplex with their targets at only one site. Thus, miRNAs negatively regulate target expression at the translational level[34]. Currently, researchers have documented an estimated number of about 1000 miRNAs encoded in the human genome and more than one-third of the expressed genes were regulated by miRNAs[34,36,37].

The action mechanisms for the decoy ODN strategy differs from the mechanisms antisense and RNAi, where the target gene expression is modulated in a post-transcriptional manner. Decoy ODN strategy is based on the competition for trans-acting factors between endogenous cis-elements present within the regulatory regions of the target gene and exogenously added decoy molecules (e.g., double-stranded DNA) mimicking the specific cis-elements. When the decoy ODN are delivered into the nucleus of target cell, the decoy ODN can bind to the free transcription factors. This results in the prevention of transcription factor interaction and the transactivation of a transcription factor-promoting target gene expression[38-41]. Therefore, decoy ODN strategy may enable a diseases treatment by modulation of endogenous transcriptional regulation. It has been used successfully in vitro and in vivo to modulate gene expression, suggesting its use in therapy also[40,42-46].

TGF-β1 is the most potent factor to accelerate liver fibrosis among a number of growth factors and cytokines for the ECM accumulation. TGF-β1 not only enhances the synthesis of ECM but also inhibits the ECM degradation by down-regulating the expression of MMPs and TIMPs induction[47-49]. Therefore, the blockage of TGF-β1 or the signaling pathway is considered as a potent therapeutic strategy for the liver fibrosis treatment. Arias et al[50] reported that adenoviral expression of TGF-β1 antisense ODN resulted in an inhibition of HSC activation. Moreover, the delivery of TGF-β1 antisense ODN prevented also the liver fibrogenesis in vivo due to obstructive bile duct ligature in rats. TGF-β1 signaling occurs through a transmembranes family and Ser/Thr kinase receptors, which are known as receptor I (TβRI) and receptor II (TβRII). An exogenous antisense TβRI and TβRII block in pig serum-induced liver fibrosis in rats[51]. Based on the reports above, TGF-β1 and signaling pathway targeted antisense strategies lead to the deactivation of activated HSCs. Hence, the deposition of ECM will be halt.

The process of ECM accumulation/degradation is also the major pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. It is important to modulate the ECM turnover, including not only the synthesis but also the degradation. The resolution of ECM accumulation is carried out by a fine balance between activities of proteinases (MMPs) and their inhibitors (TIMPs). MMPs are a family of proteolytic enzymes which are capable to degrade the ECM. The activity of MMPs is tightly regulated by its specific inhibitors TIMPs[52]. A degradation of abnormal ECM after a prolonged liver injury is inhibited due to TIMP expression by activated HSCs. During the spontaneous recovery from liver fibrosis, the TIMP-1 level decreases and the activity of collagenase and the apoptosis of HSCs increase[53]. With the purpose to antagonize the excess amounts of TIMP-1 in the liver fibrosis, it was also proved in an immune induced liver fibrosis model in rats, that TIMP-1 antisense ODN had a preventive effect on liver fibrosis progression[54]. Moreover, Nie et al[55] designed two different antisense ODNs (seq1 and seq2) targeting TIMP-2 and transfected into the rat livers by hydrodynamic injection in immune induced liver fibrosis. The TIMP-2 antisense ODN prevented the progression of liver fibrosis. These results suggest that antisense ODN is appropriate for the gene modulation in liver fibrogenesis.

Gene silencing by siRNA has evolved as a novel post-transcriptional gene silencing strategy with therapeutic potential. In the recent years there has been a considerable interest in siRNA-based gene therapy for a liver fibrosis treatment[56,57]. Most of the targeted genes are those which are critical for the HSC activation, proliferation and/or ECM synthesis and degradation which are usually up-regulated during liver fibrogenesis. Those genes include TGF-β1, PDGF and TIMPs[58-61]. Obstacles of siRNA-based therapies may be systemic, local or cellular and result in rapid excretion, low serum stability, nonspecific tissue accumulation, poor uptake by the cells and an endosomal release into cytoplasm. To overcome these side-effects, a plasmid vector (pU6shX) was employed with encoded siRNA (shRNA) against TGF-β1 in CCl4-induced murine liver fibrosis. Following TGF-β1 shRNA administration, TGF-β1 shRNA effectively silenced TGF-β1 gene expression in murine liver fibrosis. TGF-β1 shRNA also significantly inhibited the expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and type I collagen[62]. Similar trials have been employed TGF-β1 siRNA in liver fibrogenesis in vitro[63].

As discussed in the previous section, activated HSCs play a pivotal role during liver fibrogenesis. In order to effective transfer the site-specific inhibition of siRNA, several attempts have been introduced to specific approaches for activated HSCs using HSC specific ligands or promoters. Sato et al[64] employed siRNA using vitamin A-coupled liposome. In dimethylnitrosamine-induced liver fibrosis, collagen specific chaperone molecule (gp46) siRNA/vitamin A-coupled liposome effectively resolved the hepatic collagen deposition and prolonged the survival. Since this report, vitamin-A-coupled liposomal delivery system has been applied in targeting siRNA to HSCs. Chen et al[65] used glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) promoter. GFAP, an intermediate filament protein, was considered as a marker for activated and quiescent HSCs[66,67]. They applied PDGFR-β shRNA using GFAP promoter in liver fibrosis to avoid the nonspecific interference of PDGF-β gene expression in other tissues or cells. Cell-specific PDGFR-β shRNA could attenuate liver injury and liver fibrosis in rats.

Hepatocytes, which are the key parenchymal cells in the liver, contribute to the accumulation of activated myofibroblast via epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) during the liver fibrogenesis, to date[68-70]. EMT is an emerging concept in the fibrosis of adult organs speculating that this process refers to epithelial cells which underwent a transitioning to resident tissue myofibroblasts in response to persistent tissue injuries[71]. Recently, due to an accumulation of evidences it was suggested that the EMT contributes to the liver fibrosis. This may be similar to processes which occur in other organs, such as in the lung, kidney and intestine[72,73]. From this point of view, hepatocytes will be a new target for the treatment of liver fibrosis. Based on this concept, hepatocyte targeted therapies have been tried with the use of hepatocyte specific promoters (albumin promoter)[74,75] or membrane receptor (galactosylated carriers)[76-78]. Sato et al[79] reported that the galactosylated liposome/siRNA complex effectively exhibited the hepatocyte-selective gene silencing. Taken together, siRNA-mediated therapeutics could lead to an effective inhibition of liver fibrogenesis. Moreover, targeted delivery of the agents to the liver specific cells, especially HSCs and hepatocytes, may provide a solution to reduce the adverse reactions and optimize the efficacy as well.

miRNAs were recently discovered molecules which regulated the entire intracellular pathways at a post-translational level through targeting 3’-UTR of target gene mRNAs as discussed above. The number of miRNA transcripts known to be encoded human genome exceeds 1000 now. There has been an exponential growth for the regulatory roles of miRNAs in the development of diseases. Now, miRNAs are considered as another type of transcription factors[80]. Most of recent studies have focused on the roles of miRNAs in the initiation and progression of liver cancer[81], although it is shown more about the roles of miRNAs in liver fibrosis.

miRNAs can regulate the activation of HSCs and thereby regulate liver fibrosis. In rat HSCs, the down-regulation of miR-27a and 27b switch to quiescent HSC phenotype with accumulated cytoplasmic lipid droplets and a decreased HSCs proliferation[82]. A recent study indicated that miR-29b is a negative regulator for the type I collagen and SP1 in HSCs[83]. Roderburg et al[84] also demonstrated that miR-29 regulates human and murine liver fibrosis through the modulation of TGF-β1 and NF-κB signaling pathway. According to these results, miR-29 families are emerging as a very important and common regulator of liver fibrosis. Other studies[85] have analyzed the expression of miRNAs in CCl4-induced liver fibrosis model and human clinical samples by miRNA microarray analysis. They identified 4 highly expressed miRNAs (miR-199a, miR-199a*, miR-200a and miR-200b) which were significantly associated with the progression of liver fibrosis both human and mice. MiR-199a* and miR-200b directly regulates the TGFβ-induced factor and SMAD specific E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 2, which mediate the TGFβ signaling pathway. Especially, the miR-200 family regulated EMT by targeting the EMT accelerator zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 1 and survival of motor neuron protein-interacting protein 1. In addition, the coordination of aberrant expression of these miRNAs affects the liver fibrosis related genes.

From these findings, miRNAs expression profile has the potential not only to therapeutically target but also to be a novel biomarker of liver fibrosis. miRNAs are good biomarkers because they are well defined, chemically uniform, restricted to a manageable number of species and stable in cells and in the circulation[86-88]. The manipulation of the specific miRNAs during the liver fibrosis holds promises a new therapeutic approach. There are 2 different strategies to utilize the therapeutic approaches of miRNA. One of them is a miRNA replacement which utilizes short RNA duplexes to mimic miRNAs which are underexpressed in the liver fibrosis. The other is a chemically modified miRNA inhibitor with single-stranded ODNs which antagonize overexpressed miRNAs[81]. However, miRNA-based therapeutics are still on an early its stages. More studies will be necessary to understand the complex biological function and to develop effective and safe delivery methods.

The regulation of gene expression is a complex biological process which involves the transcription factor-DNA interaction for the gene transcription initiation. Thus, modulation of transcription has been considered as an important target of drugs in the biomedicine[89,90]. The transcription of a specific gene is regulated by several transcription factors which can recognize their relatively short binding sequences even in the absence of surrounding genomic DNA. By utilizing this property, decoy ODNs mimic the binding sites for transcription factor proteins and compete with promoter regions to absorb this binding activity in the cell nucleus[38,39]. This decoy ODN strategy provides a powerful tool to inhibit the expression of specific gene by modulation of endogenous transcriptional regulation.

During iterative or chronic hepatic injuries in liver fibrosis, the liver tissue is exposed, presenting repeated and overlapping waves of inflammation associated with persistently elevated expression of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines and MMPs. Following the inflammatory reactions in liver, the activation of hepatic NF-κB is observed in nonparenchymal and parenchymal liver cells[91-94]. Kupffer cells (resident macrophages of liver) show powerful NF-κB activation in response to liver injury, resulting in the production and secretion of inflammatory cytokines[95]. Son et al[96] showed that selective transfer NF-κB decoy ODN to liver macrophages in CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. Selective inhibition of NF-κB in liver macrophages showed successful inhibition of subsequent inflammation and ultimately liver fibrosis during long-term treatment of CCl4.

Another transcription factor specificity protein 1 (Sp1) also plays important roles in the regulation of matrix gene transcription like TGF-β1 and type I collagen in the liver fibrosis[97]. Generally, Sp1 is the founder member of the Sp1/KLF-like family of zinc-finger transcription factors and specifically binds to the GC-rich promoter region[98]. Chen et al[99] showed that Sp1 decoy ODN effectively inhibits proliferation and fibrotic gene synthesis of activated HSCs in vitro. Additionally, Park et al[100] demonstrated that Sp1 decoy ODN effectively blocks Sp1 binding in CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. Transfection of Sp1 decoy ODN markedly reduced TGF-β1 expression as well as matrix gene expression in vivo.

More recently, alternative structures have been explored for the design of decoy ODNs, which combine in the same molecules the binding sites for different transcription factors. To utilize this strategy, chimeric decoy ODN, which contains two or more transcription factor binding sites, was designed to enhance the effective use of decoy ODN strategy. Although chimeric decoy ODN strategy has been employed against cardiovascular diseases[101,102] and kidney fibrosis[46,103], there is little known about the effectiveness of chimeric decoy ODN strategy in liver fibrosis. Our recent study provided the first evidence of the feasibility of a chimeric decoy ODN strategy against both NF-κB and Sp1 in liver fibrosis simultaneously in vitro and in vivo. The transfection of chimeric decoy ODN significantly inhibited the activation of Sp1 and NF-κB as compared with the independent transfection of Sp1 and NF-κB in activated HSCs. In addition, chimeric decoy ODN prevented the fibrogenic and pro-inflammatory gene response in CCl4-induced liver fibrosis[104]. Taken together, decoy ODN strategy is considered one of the most useful strategies to prevent the progression of liver fibrosis and to examine the molecular mechanism of specific gene expression.

The development of gene therapy technology has steadily progressed over the past 20 years. Among the several strategies for gene therapy, small RNA- and DNA based gene therapy, which includes antisense, RNAi (siRNA and miRNA) and decoy, has attracted a lot of interest in terms of their efficacy and ease of handling. Although these therapies are specific and effective in gene regulation, there are still many unsolved issues. Table 1 shows the major advantages and disadvantages of these therapies. Small RNA and DNA are susceptible to degradation, such as nuclease, serum and cytoplasmic extracts. Additional work is needed to evaluate the efficient transfer of small RNA and DNA. For example, ODN molecules based on peptide nucleic acids (PNAs) should be taken into great consideration[105]. On the basis of PNA strategy, PNA-DNA-PNA chimeras are of great interest from several viewpoints[106,107]. Unlike ODNs, PNA-DNA-PNA chimeras are resistant to nucleases as well as to immunologic responses[108].

| Strategy | Mechanisms of action | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Antisense ODN | RNA-antisense ODN heteroduplex activates RNase H that can degrade the duplexesAntisense ODN physically block the ribosome translocation sterically by hybridization | Antisense ODN can be introduced directly into cellAvailability of chemical modification of antisense ODN | Stability in cells (endonucleolytic and exonucleolytic degradation)Modified antisense ODN stimulates the immune systemDesign and synthesis is more complicated compared with other strategies |

| siRNA | siRNA incorporated into RISC, which leads to the rapid degradation of the entire mRNA molecule | Great specificity and efficacy: thermodynamic end stability, target mRNA accessibility | Non-specific gene silencing |

| Activation of immune response | |||

| RNA degradation by endonuclease | |||

| Expensive for larger experiments | |||

| miRNA | Small, non-protein coding RNAs that guide the post-transcriptional repression of mRNA binding at 3’ UTR region | miRNA ability to regulate multiple genesCost effective for long-term experiments | Need for cloning and verification of insert |

| Activation of immune response | |||

| RNA degradation by endonuclease | |||

| Decoy ODN | Double stranded oligonucleotide containing an enhancer cis-element | Specifically inhibits transcription factor function | Transfection efficiency and delivery to cells |

| Target transcription factor binds to decoy ODN and block the interaction of target gene transcription | Allows for the regulation of endogenous and pathological gene expression | DNA degradation by endonuclease |

Only a few clinical studies about liver fibrosis with less success but remarkable lessons were conducted yet. Antifibrotic trials for the treatment of HCV cirrhosis were conducted with drugs which were not successfully indicated. The fibrosis continued in their progress even in advanced diseases where the HCV was not cured, albeit a nonlinear rates[109]. Recent findings from integrative and mechanism-based profiling studies have provided important information about the roles of small RNA- and DNA based therapeutic strategies in liver fibrosis. These studies could improve the current understanding of the molecular mechanisms of chronic liver diseases. Table 2 briefly summarizes that small RNA- and DNA-based therapeutic approaches for liver fibrosis have been focused on the antifibrotic agents, which are able to reduce hepatic inflammation, HSC activation, the accumulation of ECM and the TGF-β1 expression. In addition, delivery of small RNA- and DNA with cell-specific ligands or driven by cell-specific promoters or transcriptional regulatory units are promising strategies for a direct cell specific gene expression for the treatment of liver fibrosis. However, the non-specific expression of target gene in all of transduced cells remains concerning. A better understanding of limitations for small RNA- and DNA-based gene therapy will greatly facilitate approaches to increase the potency in the treatment of liver fibrosis. Even if not discussed in this article, other delivery technologies such as oral delivery, can enhance the performance and/or the patient convenience of small RNA- and DNA-based gene therapy[110]. Therefore, more clinical trials based on small RNA- and DNA-based gene therapy, particularly in liver fibrosis are expecting in the near future.

| Strategy | Target gene | Biological effects | Ref. |

| Antisense ODN | TGF-β1 | Inhibition of liver fibrogenesis in vivo (bile duct ligation) and in vitro (activated HSCs) | [50] |

| TβRI and TβRII | Exogenous antisense TβRI and TβRII block in pig serum induced liver fibrosis | [51] | |

| TIMP-1 | Preventive effect on immune induced liver fibrosis progression | [54] | |

| TIMP-2 (seq1 and seq2) | Hydrodynamic injection of TIMP-2 antisense prevented the progression of liver fibrosis | [55] | |

| siRNA | TGF-β1 | TGF-β1 shRNA effectively inhibited CCl4-induced liver fibrosis | [62] |

| TGF-β1 | Inhibition of the expression of TGF-β1 and inflammatory cytokine in HSC-T6 | [63] | |

| Collagen specific chaperon (gp46) | Effectively resolved the hepatic collagen deposition and prolonged survival in DMN-induced liver fibrosis | [64] | |

| PDGF receptor beta small subunit (GFAP promoter) | HSCs-specific PDGFR-beta shRNA attenuates CCl4-induced acute liver injury and bile duct ligation-induced chronic liver fibrosis | [65] | |

| Ubc 13 | Galactosylated liposome/siRNA complex effectively exhibited the hepatocyte selective gene silencing | [79] | |

| miRNA | miR-27a and 27b | Down regulation of miR-27a and 27b changed from activated HSC to quiescent HSC | [82] |

| miR-29b | Negative regulator for the type I collagen and Sp1 in HSC | [83] | |

| miR-29 family | Modulation of TGF-β1 and NF-κB signaling pathway in CCl4-induced liver fibrosis | [84] | |

| miR-199a, miR-199a*, miR200a and miR-200b | Highly expressed miRNAs by miRNA microarray analysis in CCl4-induced liver fibrosis | [85] | |

| Decoy ODN | NF-κB | Inhibition of inflammatory changes and fibrosis during CCl4-induced liver fibrosis | [96] |

| Sp1 | Inhibition of proliferation and fibrotic gene synthesis in activated HSCs | [99] | |

| Sp1 | Inhibition of TGF-β1 and matrix gene expression in CCl4-induced liver fibrosis | [100] | |

| NF-κB and Sp1 | Inhibition of fibrogenic and proinflammatory response in CCl4-induced liver fibrosis | [104] |

In conclusion, the application of small RNA- and DNA-based gene therapy has opened a new door for the treatment of liver fibrosis. Although many questions remain unsolved, the results to date are very encouraging; small RNA- and DNA-based gene therapy should join small molecules and protein-based therapeutics as the third discovery system in the treatment of liver fibrosis.

| 1. | Parola M, Pinzani M. Hepatic wound repair. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2009;2:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Crockett-Torabi E. Selectins and mechanisms of signal transduction. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;63:1-14. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Canbay A, Feldstein AE, Higuchi H, Werneburg N, Grambihler A, Bronk SF, Gores GJ. Kupffer cell engulfment of apoptotic bodies stimulates death ligand and cytokine expression. Hepatology. 2003;38:1188-1198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 364] [Cited by in RCA: 354] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Kojima Y, Suzuki S, Tsuchiya Y, Konno H, Baba S, Nakamura S. Regulation of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine responses by Kupffer cells in endotoxin-enhanced reperfusion injury after total hepatic ischemia. Transpl Int. 2003;16:231-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Prosser CC, Yen RD, Wu J. Molecular therapy for hepatic injury and fibrosis: where are we? World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:509-515. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Kershenobich Stalnikowitz D, Weissbrod AB. Liver fibrosis and inflammation. A review. Ann Hepatol. 2003;2:159-163. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Asrani SK, Kamath PS. Natural history of cirrhosis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15:308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1655-1669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2139] [Cited by in RCA: 2191] [Article Influence: 121.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Lee UE, Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25:195-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 735] [Cited by in RCA: 752] [Article Influence: 50.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Friedman SL. Molecular regulation of hepatic fibrosis, an integrated cellular response to tissue injury. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2247-2250. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Friedman SL. Liver fibrosis -- from bench to bedside. J Hepatol. 2003;38 Suppl 1:S38-S53. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Bataller R, Brenner DA. Liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:209-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3381] [Cited by in RCA: 4215] [Article Influence: 200.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (11)] |

| 13. | Shek FW, Benyon RC. How can transforming growth factor beta be targeted usefully to combat liver fibrosis? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:123-126. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Gressner AM, Weiskirchen R. Modern pathogenetic concepts of liver fibrosis suggest stellate cells and TGF-beta as major players and therapeutic targets. J Cell Mol Med. 2006;10:76-99. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Said A, Lucey MR. Liver transplantation: an update 2008. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24:339-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Isaka Y, Imai E, Takahara S, Rakugi H. Oligonucleotidic therapeutics. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2008;3:991-996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bennett CF, Swayze EE. RNA targeting therapeutics: molecular mechanisms of antisense oligonucleotides as a therapeutic platform. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:259-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 952] [Cited by in RCA: 1078] [Article Influence: 67.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Liu Q, Paroo Z. Biochemical principles of small RNA pathways. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:295-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zamecnik PC, Stephenson ML. Inhibition of Rous sarcoma virus replication and cell transformation by a specific oligodeoxynucleotide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:280-284. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Stephenson ML, Zamecnik PC. Inhibition of Rous sarcoma viral RNA translation by a specific oligodeoxyribonucleotide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:285-288. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Toub N, Malvy C, Fattal E, Couvreur P. Innovative nanotechnologies for the delivery of oligonucleotides and siRNA. Biomed Pharmacother. 2006;60:607-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sepp-Lorenzino L, Ruddy M. Challenges and opportunities for local and systemic delivery of siRNA and antisense oligonucleotides. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:628-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Crooke ST. Vitravene--another piece in the mosaic. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 1998;8:vii-viii. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Aboul-Fadl T. Antisense oligonucleotide technologies in drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2006;1:285-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sahu NK, Shilakari G, Nayak A, Kohli DV. Antisense technology: a selective tool for gene expression regulation and gene targeting. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2007;8:291-304. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Rayburn ER, Zhang R. Antisense, RNAi, and gene silencing strategies for therapy: mission possible or impossible? Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:513-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10522] [Cited by in RCA: 10317] [Article Influence: 368.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 28. | Hannon GJ. RNA interference. Nature. 2002;418:244-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3058] [Cited by in RCA: 2916] [Article Influence: 121.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Nykänen A, Haley B, Zamore PD. ATP requirements and small interfering RNA structure in the RNA interference pathway. Cell. 2001;107:309-321. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Hammond SM, Bernstein E, Beach D, Hannon GJ. An RNA-directed nuclease mediates post-transcriptional gene silencing in Drosophila cells. Nature. 2000;404:293-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2080] [Cited by in RCA: 2028] [Article Influence: 78.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Dykxhoorn DM, Novina CD, Sharp PA. Killing the messenger: short RNAs that silence gene expression. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:457-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 839] [Cited by in RCA: 808] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Schwarz DS, Hutvágner G, Du T, Xu Z, Aronin N, Zamore PD. Asymmetry in the assembly of the RNAi enzyme complex. Cell. 2003;115:199-208. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Couzin J. Breakthrough of the year. Small RNAs make big splash. Science. 2002;298:2296-2297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281-297. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Lee Y, Kim M, Han J, Yeom KH, Lee S, Baek SH, Kim VN. MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 2004;23:4051-4060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2902] [Cited by in RCA: 3037] [Article Influence: 138.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Eulalio A, Huntzinger E, Izaurralde E. Getting to the root of miRNA-mediated gene silencing. Cell. 2008;132:9-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 743] [Cited by in RCA: 816] [Article Influence: 45.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Selbach M, Schwanhäusser B, Thierfelder N, Fang Z, Khanin R, Rajewsky N. Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature. 2008;455:58-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2577] [Cited by in RCA: 2747] [Article Influence: 152.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Mann MJ, Dzau VJ. Therapeutic applications of transcription factor decoy oligonucleotides. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1071-1075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Morishita R, Sugimoto T, Aoki M, Kida I, Tomita N, Moriguchi A, Maeda K, Sawa Y, Kaneda Y, Higaki J. In vivo transfection of cis element “decoy” against nuclear factor-kappaB binding site prevents myocardial infarction. Nat Med. 1997;3:894-899. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Tomita T, Takano H, Tomita N, Morishita R, Kaneko M, Shi K, Takahi K, Nakase T, Kaneda Y, Yoshikawa H. Transcription factor decoy for NFkappaB inhibits cytokine and adhesion molecule expressions in synovial cells derived from rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39:749-757. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Morishita R, Gibbons GH, Horiuchi M, Ellison KE, Nakama M, Zhang L, Kaneda Y, Ogihara T, Dzau VJ. A gene therapy strategy using a transcription factor decoy of the E2F binding site inhibits smooth muscle proliferation in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5855-5859. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Morishita R, Higaki J, Tomita N, Aoki M, Moriguchi A, Tamura K, Murakami K, Kaneda Y, Ogihara T. Role of transcriptional cis-elements, angiotensinogen gene-activating elements, of angiotensinogen gene in blood pressure regulation. Hypertension. 1996;27:502-507. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Chae YM, Park KK, Lee IK, Kim JK, Kim CH, Chang YC. Ring-Sp1 decoy oligonucleotide effectively suppresses extracellular matrix gene expression and fibrosis of rat kidney induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction. Gene Ther. 2006;13:430-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Kim KH, Lee ES, Cha SH, Park JH, Park JS, Chang YC, Park KK. Transcriptional regulation of NF-kappaB by ring type decoy oligodeoxynucleotide in an animal model of nephropathy. Exp Mol Pathol. 2009;86:114-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Sung WJ, Kim KH, Kim YJ, Chang YC, Lee IH, Park KK. Antifibrotic effect of synthetic Smad/Sp1 chimeric decoy oligodeoxynucleotide through the regulation of epithelial mesenchymal transition in unilateral ureteral obstruction model of mice. Exp Mol Pathol. 2013;95:136-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Tsukamoto H. Cytokine regulation of hepatic stellate cells in liver fibrosis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:911-916. [PubMed] |

| 48. | Benyon RC, Arthur MJ. Extracellular matrix degradation and the role of hepatic stellate cells. Semin Liver Dis. 2001;21:373-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 358] [Cited by in RCA: 374] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Knittel T, Mehde M, Grundmann A, Saile B, Scharf JG, Ramadori G. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors during hepatic tissue repair in the rat. Histochem Cell Biol. 2000;113:443-453. [PubMed] |

| 50. | Arias M, Sauer-Lehnen S, Treptau J, Janoschek N, Theuerkauf I, Buettner R, Gressner AM, Weiskirchen R. Adenoviral expression of a transforming growth factor-beta1 antisense mRNA is effective in preventing liver fibrosis in bile-duct ligated rats. BMC Gastroenterol. 2003;3:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Jiang W, Yang CQ, Liu WB, Wang YQ, He BM, Wang JY. Blockage of transforming growth factor beta receptors prevents progression of pig serum-induced rat liver fibrosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1634-1638. [PubMed] |

| 52. | Schuppan D, Ruehl M, Somasundaram R, Hahn EG. Matrix as a modulator of hepatic fibrogenesis. Semin Liver Dis. 2001;21:351-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 391] [Cited by in RCA: 394] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Liu WB, Yang CQ, Jiang W, Wang YQ, Guo JS, He BM, Wang JY. Inhibition on the production of collagen type I, III of activated hepatic stellate cells by antisense TIMP-1 recombinant plasmid. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:316-319. [PubMed] |

| 54. | Nie QH, Cheng YQ, Xie YM, Zhou YX, Cao YZ. Inhibiting effect of antisense oligonucleotides phosphorthioate on gene expression of TIMP-1 in rat liver fibrosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:363-369. [PubMed] |

| 55. | Nie QH, Zhu CL, Zhang YF, Yang J, Zhang JC, Gao RT. Inhibitory effect of antisense oligonucleotide targeting TIMP-2 on immune-induced liver fibrosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1286-1295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Singh S, Narang AS, Mahato RI. Subcellular fate and off-target effects of siRNA, shRNA, and miRNA. Pharm Res. 2011;28:2996-3015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Hu PF, Xie WF. Targeted RNA interference for hepatic fibrosis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2009;9:1305-1312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Hu YB, Li DG, Lu HM. Modified synthetic siRNA targeting tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 inhibits hepatic fibrogenesis in rats. J Gene Med. 2007;9:217-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Hu PF, Chen H, Zhong W, Lin Y, Zhang X, Chen YX, Xie WF. Adenovirus-mediated transfer of siRNA against PAI-1 mRNA ameliorates hepatic fibrosis in rats. J Hepatol. 2009;51:102-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Chen SW, Zhang XR, Wang CZ, Chen WZ, Xie WF, Chen YX. RNA interference targeting the platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta subunit ameliorates experimental hepatic fibrosis in rats. Liver Int. 2008;28:1446-1457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Lang Q, Liu Q, Xu N, Qian KL, Qi JH, Sun YC, Xiao L, Shi XF. The antifibrotic effects of TGF-β1 siRNA on hepatic fibrosis in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;409:448-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Kim KH, Kim HC, Hwang MY, Oh HK, Lee TS, Chang YC, Song HJ, Won NH, Park KK. The antifibrotic effect of TGF-beta1 siRNAs in murine model of liver cirrhosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:1072-1078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Cheng K, Yang N, Mahato RI. TGF-beta1 gene silencing for treating liver fibrosis. Mol Pharm. 2009;6:772-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Sato Y, Murase K, Kato J, Kobune M, Sato T, Kawano Y, Takimoto R, Takada K, Miyanishi K, Matsunaga T. Resolution of liver cirrhosis using vitamin A-coupled liposomes to deliver siRNA against a collagen-specific chaperone. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:431-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 416] [Cited by in RCA: 475] [Article Influence: 26.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Chen SW, Chen YX, Zhang XR, Qian H, Chen WZ, Xie WF. Targeted inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta subunit in hepatic stellate cells ameliorates hepatic fibrosis in rats. Gene Ther. 2008;15:1424-1435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Cassiman D, Libbrecht L, Desmet V, Denef C, Roskams T. Hepatic stellate cell/myofibroblast subpopulations in fibrotic human and rat livers. J Hepatol. 2002;36:200-209. [PubMed] |

| 67. | Gard AL, White FP, Dutton GR. Extra-neural glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) immunoreactivity in perisinusoidal stellate cells of rat liver. J Neuroimmunol. 1985;8:359-375. [PubMed] |

| 68. | Fausto N. Liver regeneration and repair: hepatocytes, progenitor cells, and stem cells. Hepatology. 2004;39:1477-1487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 537] [Cited by in RCA: 518] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Zeisberg M, Yang C, Martino M, Duncan MB, Rieder F, Tanjore H, Kalluri R. Fibroblasts derive from hepatocytes in liver fibrosis via epithelial to mesenchymal transition. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:23337-23347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 587] [Cited by in RCA: 654] [Article Influence: 34.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Kaimori A, Potter J, Kaimori JY, Wang C, Mezey E, Koteish A. Transforming growth factor-beta1 induces an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition state in mouse hepatocytes in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22089-22101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Kalluri R, Neilson EG. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its implications for fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1776-1784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 1057] [Article Influence: 48.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1420-1428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6575] [Cited by in RCA: 8105] [Article Influence: 476.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Xue ZF, Wu XM, Liu M. Hepatic regeneration and the epithelial to mesenchymal transition. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1380-1386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Han C, Li G, Lim K, DeFrances MC, Gandhi CR, Wu T. Transgenic expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in hepatocytes accelerates endotoxin-induced acute liver failure. J Immunol. 2008;181:8027-8035. [PubMed] |

| 75. | Gkretsi V, Apte U, Mars WM, Bowen WC, Luo JH, Yang Y, Yu YP, Orr A, St-Arnaud R, Dedhar S. Liver-specific ablation of integrin-linked kinase in mice results in abnormal histology, enhanced cell proliferation, and hepatomegaly. Hepatology. 2008;48:1932-1941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Díez S, Navarro G, de ILarduya CT. In vivo targeted gene delivery by cationic nanoparticles for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gene Med. 2009;11:38-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Watanabe T, Umehara T, Yasui F, Nakagawa S, Yano J, Ohgi T, Sonoke S, Satoh K, Inoue K, Yoshiba M. Liver target delivery of small interfering RNA to the HCV gene by lactosylated cationic liposome. J Hepatol. 2007;47:744-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Fumoto S, Kawakami S, Ito Y, Shigeta K, Yamashita F, Hashida M. Enhanced hepatocyte-selective in vivo gene expression by stabilized galactosylated liposome/plasmid DNA complex using sodium chloride for complex formation. Mol Ther. 2004;10:719-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Sato A, Takagi M, Shimamoto A, Kawakami S, Hashida M. Small interfering RNA delivery to the liver by intravenous administration of galactosylated cationic liposomes in mice. Biomaterials. 2007;28:1434-1442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Hobert O. Gene regulation by transcription factors and microRNAs. Science. 2008;319:1785-1786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 662] [Cited by in RCA: 659] [Article Influence: 36.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Wang XW, Heegaard NH, Orum H. MicroRNAs in liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1431-1443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Ji J, Zhang J, Huang G, Qian J, Wang X, Mei S. Over-expressed microRNA-27a and 27b influence fat accumulation and cell proliferation during rat hepatic stellate cell activation. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:759-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Ogawa T, Iizuka M, Sekiya Y, Yoshizato K, Ikeda K, Kawada N. Suppression of type I collagen production by microRNA-29b in cultured human stellate cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391:316-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Roderburg C, Urban GW, Bettermann K, Vucur M, Zimmermann H, Schmidt S, Janssen J, Koppe C, Knolle P, Castoldi M. Micro-RNA profiling reveals a role for miR-29 in human and murine liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 2011;53:209-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 656] [Cited by in RCA: 666] [Article Influence: 44.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Murakami Y, Toyoda H, Tanaka M, Kuroda M, Harada Y, Matsuda F, Tajima A, Kosaka N, Ochiya T, Shimotohno K. The progression of liver fibrosis is related with overexpression of the miR-199 and 200 families. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Mitchell PS, Parkin RK, Kroh EM, Fritz BR, Wyman SK, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, Peterson A, Noteboom J, O’Briant KC, Allen A. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10513-10518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5636] [Cited by in RCA: 6414] [Article Influence: 356.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Liu A, Tetzlaff MT, Vanbelle P, Elder D, Feldman M, Tobias JW, Sepulveda AR, Xu X. MicroRNA expression profiling outperforms mRNA expression profiling in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2009;2:519-527. [PubMed] |

| 88. | de Planell-Saguer M, Rodicio MC. Analytical aspects of microRNA in diagnostics: a review. Anal Chim Acta. 2011;699:134-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Martiniello-Wilks R, Tsatralis T, Russell P, Brookes DE, Zandvliet D, Lockett LJ, Both GW, Molloy PL, Russell PJ. Transcription-targeted gene therapy for androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2002;9:443-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Licht JD. Targeting aberrant transcriptional repression in leukemia: a therapeutic reality? J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1277-1278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Ribeiro PS, Cortez-Pinto H, Solá S, Castro RE, Ramalho RM, Baptista A, Moura MC, Camilo ME, Rodrigues CM. Hepatocyte apoptosis, expression of death receptors, and activation of NF-kappaB in the liver of nonalcoholic and alcoholic steatohepatitis patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1708-1717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 92. | Spitzer JA, Zheng M, Kolls JK, Vande Stouwe C, Spitzer JJ. Ethanol and LPS modulate NF-kappaB activation, inducible NO synthase and COX-2 gene expression in rat liver cells in vivo. Front Biosci. 2002;7:a99-108. [PubMed] |

| 93. | Elsharkawy AM, Wright MC, Hay RT, Arthur MJ, Hughes T, Bahr MJ, Degitz K, Mann DA. Persistent activation of nuclear factor-kappaB in cultured rat hepatic stellate cells involves the induction of potentially novel Rel-like factors and prolonged changes in the expression of IkappaB family proteins. Hepatology. 1999;30:761-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Chaisson ML, Brooling JT, Ladiges W, Tsai S, Fausto N. Hepatocyte-specific inhibition of NF-kappaB leads to apoptosis after TNF treatment, but not after partial hepatectomy. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:193-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Racanelli V, Rehermann B. The liver as an immunological organ. Hepatology. 2006;43:S54-S62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 870] [Cited by in RCA: 993] [Article Influence: 49.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Son G, Iimuro Y, Seki E, Hirano T, Kaneda Y, Fujimoto J. Selective inactivation of NF-kappaB in the liver using NF-kappaB decoy suppresses CCl4-induced liver injury and fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G631-G639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Verrecchia F, Rossert J, Mauviel A. Blocking sp1 transcription factor broadly inhibits extracellular matrix gene expression in vitro and in vivo: implications for the treatment of tissue fibrosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116:755-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Geiser AG, Busam KJ, Kim SJ, Lafyatis R, O’Reilly MA, Webbink R, Roberts AB, Sporn MB. Regulation of the transforming growth factor-beta 1 and -beta 3 promoters by transcription factor Sp1. Gene. 1993;129:223-228. [PubMed] |

| 99. | Chen H, Zhou Y, Chen KQ, An G, Ji SY, Chen QK. Anti-fibrotic effects via regulation of transcription factor Sp1 on hepatic stellate cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2012;29:51-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Park JH, Jo JH, Kim KH, Kim SJ, Lee WR, Park KK, Park JB. Antifibrotic effect through the regulation of transcription factor using ring type-Sp1 decoy oligodeoxynucleotide in carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis. J Gene Med. 2009;11:824-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Miyake T, Aoki M, Morishita R. Inhibition of anastomotic intimal hyperplasia using a chimeric decoy strategy against NFkappaB and E2F in a rabbit model. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:706-714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Miyake T, Aoki M, Osako MK, Shimamura M, Nakagami H, Morishita R. Systemic administration of ribbon-type decoy oligodeoxynucleotide against nuclear factor κB and ets prevents abdominal aortic aneurysm in rat model. Mol Ther. 2011;19:181-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Kim KH, Park JH, Lee WR, Park JS, Kim HC, Park KK. The inhibitory effect of chimeric decoy oligodeoxynucleotide against NF-κB and Sp1 in renal interstitial fibrosis. J Mol Med (Berl). 2013;91:573-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Lee WR, Kim KH, An HJ, Park YY, Kim KS, Lee CK, Min BK, Park KK. Effects of chimeric decoy oligodeoxynucleotide in the regulation of transcription factors NF-κB and Sp1 in an animal model of atherosclerosis. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;112:236-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Nielsen PE, Egholm M, Berg RH, Buchardt O. Sequence-selective recognition of DNA by strand displacement with a thymine-substituted polyamide. Science. 1991;254:1497-1500. [PubMed] |

| 106. | Uhlmann E. Peptide nucleic acids (PNA) and PNA-DNA chimeras: from high binding affinity towards biological function. Biol Chem. 2001;379:1045-1052. [PubMed] |

| 107. | Romanelli A, Pedone C, Saviano M, Bianchi N, Borgatti M, Mischiati C, Gambari R. Molecular interactions with nuclear factor kappaB (NF-kappaB) transcription factors of a PNA-DNA chimera mimicking NF-kappaB binding sites. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:6066-6075. [PubMed] |

| 108. | Ganguly S, Chaubey B, Tripathi S, Upadhyay A, Neti PV, Howell RW, Pandey VN. Pharmacokinetic analysis of polyamide nucleic-acid-cell penetrating peptide conjugates targeted against HIV-1 transactivation response element. Oligonucleotides. 2008;18:277-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 109. | Benvegnù L, Gios M, Boccato S, Alberti A. Natural history of compensated viral cirrhosis: a prospective study on the incidence and hierarchy of major complications. Gut. 2004;53:744-749. [PubMed] |

| 110. | Akhtar S. Oral delivery of siRNA and antisense oligonucleotides. J Drug Target. 2009;17:491-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewer: Amarapurkar DN, Nakajima H, Niu ZS, Prieto J, Roeb E, Trifan A, Utama A S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN