Published online Aug 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i29.9744

Revised: March 13, 2014

Accepted: May 19, 2014

Published online: August 7, 2014

Processing time: 275 Days and 7.8 Hours

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains one of the most common malignancies in the world. Although surgical resection combined with adjuvant therapy is effective at the early stages of the disease, resistance to conventional therapies is frequently observed in advanced stages, where treatments become ineffective. Resistance to cisplatin, irinotecan and 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy has been shown to involve mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling and recent studies identified p38α MAPK as a mediator of resistance to various agents in CRC patients. Studies published in the last decade showed a dual role for the p38α pathway in mammals. Its role as a negative regulator of proliferation has been reported in both normal (including cardiomyocytes, hepatocytes, fibroblasts, hematopoietic and lung cells) and cancer cells (colon, prostate, breast, lung tumor cells). This function is mediated by the negative regulation of cell cycle progression and the transduction of some apoptotic stimuli. However, despite its anti-proliferative and tumor suppressor activity in some tissues, the p38α pathway may also acquire an oncogenic role involving cancer related-processes such as cell metabolism, invasion, inflammation and angiogenesis. In this review, we summarize current knowledge about the predominant role of the p38α MAPK pathway in CRC development and chemoresistance. In our view, this might help establish the therapeutic potential of the targeted manipulation of this pathway in clinical settings.

Core tip: The pro-apoptotic effects of p38α activation are long recognized; however, a significant number of reports describes the involvement of p38α in cancer-specific metabolism, survival, proliferation, and chemoresistance of colorectal cancer cells and tissues. p38α blockade exerts its chemosensitizing effects through nuclear accumulation of FoxO3A and activation of its pro-apoptotic gene expression program, thereby improving the efficacy of anti-cancer treatments. Apoptosis induction upon p38α inhibition requires Bax, which may thus serve as a predictive bio-marker for p38α-targeted therapy response. The novel role described for the p38-FoxO3A axis in chemoresistance might offer new options for combined therapies and personalized medicine approaches.

- Citation: Grossi V, Peserico A, Tezil T, Simone C. p38α MAPK pathway: A key factor in colorectal cancer therapy and chemoresistance. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(29): 9744-9758

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i29/9744.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i29.9744

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most frequent cancer in males and the second in females. The majority of CRC patients have sporadic disease with no apparent evidence of inheritance, while the remaining 25% have a family history of CRC suggesting a hereditary contribution, exposure to common high risk factors among family members, or a combination of both. Genetic mutations have been identified as the cause of inherited cancer risk in some tumor-prone families; these mutations are estimated to account for only 5% to 6% of CRC cases overall[1]. The knowledge derived from the study of syndromes with Mendelian dominant inheritance, which are characterized by a primary predisposition to benign or malignant tumors of the large bowel, has provided important clues regarding the molecular events driving CRC progression from normal epithelium to adenoma (mutations of APC/β-catenin, KRAS/BRAF and then DCC/SMAD2/SMAD4/TGFβRII) to carcinoma [PI3KCA, PTEN, p53, BAX, with the involvement of the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes MLH1, MSH2, PMS2 and MSH6].

Current treatment for CRC is based on combination therapies, which in most cases include surgery, local radiotherapy and chemotherapy. The type and timing of treatment depend on stage classification. Besides, pre-operative therapy for colorectal cancer has been used before surgery, resulting in improved quality of surgery, reduced toxic effects and increased radiosensitivity. The main disadvantage of pre-operative chemoradiotherapy is related to possible over-treatment of patients with early stage or undetected metastatic disease before surgery.

Current clinical trials keep on investigating the incorporation of more effective combination chemotherapies into the multimodality treatment of this disease. Currently, 5-FU combined with leucovorin and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) is the recommended first-line chemotherapy for CRC. Other frequently used compounds include capecitabine, a more convenient alternative to intravenous infusions of 5-FU for patients who are able to tolerate oral chemotherapy, and platinum-based drugs, such as oxaliplatin and cisplatin[2-4]. Oxaliplatin is used in combination with leucovorin and 5-FU in the FOLFOX regimen. In addition, targeted therapies with monoclonal antibodies designed to inhibit EGF (such as cetuximab or panitumumab) or VEGF (bevacizumab) signaling have been proven of potential benefit in addition to standard chemoradiotherapy[5].

Clinical trials are now directed to evaluate new drug combinations, treatment schedules, and radiotherapy approaches, and to set up new methods of diagnostic imaging with the aim of enhancing tumor regression, increasing overall survival, and improving the quality of life for CRC patients.

There is still much to be learned about the treatment of colorectal cancers and increasing efforts are needed to complement traditional chemotherapy with targeted molecular approaches.

MAPKs are expressed in all cell types and regulate a variety of physiological processes such as cell growth, metabolism, differentiation and cell death. To date, six distinct groups of MAPKs have been characterized in mammals: the extracellular signal-regulated kinases ERK 1/2, ERK 3/4, ERK5, ERK 7/8, the Jun N-terminal kinases JNK 1/2/3 and the p38 MAPKs p38α/β/γ/δ[6,7].

MAPK signaling shows a cascade organization, in which activation of upstream kinases by receptors leads to sequential activation of a MAPK module (MAPKKK, MAPKK, MAPK). In this context, specific interactions between MAPKs and their substrates are crucial for mediating signaling input and output[8,9]. Indeed, mechanisms are described that limit protein interactions to preserve signaling specificity. In particular, MAPKs only phosphorylate the consensus motif S/TP in their target proteins and a second level of specificity is warranted by a conserved docking domain that binds kinases allowing substrate phosphorylation[10]. In these complexes, structural scaffold proteins link together the components of the signaling pathway to assure effective signaling transmission between kinases.

p38 MAPKs are a family of serine/threonine-directed kinases classified as “stress-activated” kinases. Activation of p38 MAPKs has been observed in response to a variety of extracellular stimuli in different organisms, and p38 homologues have been identified in yeast (hog1 and Spc/Sty1), fruit fly (p38a/b/c), worm (pmk-2) and frog (p38)[11-13]. In yeast, the p38 pathway is involved in the response to extracellular stress stimuli and cell cycle-related events[14,15]. Mammalian p38 MAPKs play similar roles and their activation allows cells to interpret a wide range of external signals and respond appropriately by generating a plethora of different biological effects such as inflammation, differentiation, cell proliferation and survival in a tissue-specific and signal-dependent manner[16,17].

In mammals, four genes have been identified that encode p38 MAPKs: MAPK14 (p38α), MAPK11 (p38β), MAPK12 (p38γ) and MAPK13 (p38δ). p38α and p38β are closely related proteins that might have overlapping functions. While p38α and p38β expression is abundant in most tissues, p38γ and δ seem to be expressed in a tissue-specific manner, e.g., p38γ is detected in muscle and p38δ is predominant in skin, small intestine and kidney[18,19]. Besides being tissue-specific, the expression profile of p38 isoforms also seems to be influenced by the differentiation status of the cell. For example, undifferentiated intestinal epithelial cells express the α, β and γ isoforms, while differentiated cells express the α, γ and δ isoforms[20,21]. Additionally, three alternative splicing isoforms of the MAPK14 gene have been reported. The Mxi2 variant is identical to p38α in amino acids 1-280 and showed reduced binding of p38 MAPK substrates; however, it can bind to ERK1/2 MAPKs, modulating their nuclear import[22-24]. The Exip variant has a unique 53-amino acid C-terminus and is insensitive to usual activating treatments; nevertheless, it is able to regulate the NFκB pathway[25]. The CSB1 variant shows a 25 amino acids difference in its internal sequence, but its contribution is unknown[22].

Various combinations of upstream kinases regulate the activation of p38 isoforms. There are two major MAPKKs known to activate p38: MAPKK3 and MAPKK6, which are activated by their upstream kinases, such as MTK1 (also known as MEKK4) and the apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1)[19], but other MAPKK-independent mechanisms involving the growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible protein alpha (GADD45α) and the ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein (ATR) have also been described[26,27]. p38 MAPK is relatively inactive in its non-phosphorylated form and becomes rapidly activated by phosphorylation of two Thr-Gly-Tyr motifs[28,29]. Phosphorylated p38 proteins can activate several transcription factors, such as ATF-2, CHOP-1, MEF-2, p53, and Elk-1, but also a variety of kinases, including MNK1, MNK2, MSK1, PRAK, MAPKAPK2 and MAPKAPK3, that are involved in controlling cytoplasmic and/or nuclear signaling networks and response to cytokines, growth factors, toxins and pharmacological drugs.

Uncontrolled proliferation is a result of altered signaling mechanisms and a hallmark of cancer[30]. The genetic basis of signaling cascade deregulation relies on somatic mutations in components of these pathways, as reported in a large-scale screening study on the status of protein kinases in tumors. However, the functional meaning of these mutations remains still unclear and genetic alterations cannot explain, per se, the loss of intracellular equilibrium in cancer[31].

The p38 MAPK pathway, together with various signaling cascades such as JNK, ERK, AMPK and PI3K[30,32,33], regulates the balance between cell survival and cell death with direct effects on the development of various cancers. The tight regulation of survival/death signals by p38 MAPKs can result in opposite molecular functions in tumor development. Indeed, p38 MAPKs can play a dual role: they can either mediate cell survival or promote cell death through different mechanisms.

Most reports support the pro-apoptotic role of p38 MAPKs; for example, p38α and/or p38β are mediators of apoptosis in several cell types such as neurons[34-37] or cardiac cells[38-40]. In other cell types, p38 MAPKs activate apoptosis through transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms, upon stimulation with TNF-α[41], TGF-β[42] or oxidative stress[43]. Moreover, p38α sensitizes cardiomyocytes and MEF-derived cell lines to apoptosis induced by different stimuli through up-regulation of the pro-apoptotic proteins Fas and Bax and down-regulation of the activity of the ERK and Akt survival pathways[44,45]. In accordance with these observations, overexpression of p38α enhances apoptosis induced by the constitutive active mutant MKK3bE in cardiomyocytes; however, overexpression of p38β promotes cell survival[46].

The role of p38 as a tumor suppressor has also been highlighted by using genetically modified mouse models. Several studies taking advantage of mouse models deficient for p38 or its upstream activators (such as MAPKKs, GADD45α, MAPK5) demonstrated higher susceptibility to tumor development[47-50]. Concordant with the anti-tumorigenic function of p38, in some types of cancer inactivation of tumor suppressor pathways is promoted by the up-regulation of negative regulators of p38 MAPK, such as the phosphatases DUSP26 and PPM1D, and inhibitors of MAPKKKs upstream activators (e.g., ASK1 and GST-proteins)[51-53].

p38α negatively regulates malignant transformation induced by oncogenic H-Ras, and several mechanisms have been proposed to explain this putative tumor-suppressor role, including inhibition of the ERK pathway[54], induction of premature senescence[55], stimulation of p53-dependent cell cycle arrest[51] and upregulation of cell cycle inhibitors, such as p16INK4a[49] and p21Cip1[56]. Other reports indicate that p38α may antagonize malignant transformation induced by N-Ras in fibroblasts[57] and by K-Ras in colon cancer cells[58], although the mechanisms involved are poorly understood.

While p38 signaling has been shown to act as a tumor suppressor, this function seems to be effective mainly at the onset of cellular transformation[59-61], since in various cell lines p38 has been shown to enhance tumor cell growth after acquisition of the malignant phenotype. Enhanced p38 MAPK phosphorylation has been correlated with poor overall survival in patients with HER-2 negative breast cancer[62] or with hepatocellular carcinoma[63]. Moreover p38 MAPK is involved in sustaining tumor growth in other types of cancer including follicular lymphoma, lung, thyroid, colorectal, ovarian[64,65] and breast carcinomas, as well as gliomas and head and neck squamous cell carcinomas[66-69]. In these cases, depending on the type and stage of the tumor, cancer cells with pro-tumorigenic activation of the p38 MAPK pathway may have a selective advantage.

The potential pro-tumorigenic role of p38α signaling is based on correlations with bad prognosis in cancer, and there is evidence that this pathway may contribute to the survival or proliferation of cancer cell lines from different origins, including breast[70], colorectal[71], prostate[72] or skin[73]. In addition, p38α is involved in cancer cell metabolism by driving HIF1α stabilization[74], in chondrosarcoma cell proliferation[75] and in tumor dormancy[76]. Typical features of cancer aggressiveness, such as migration and invasion, are also positively regulated by p38 MAPK activation in breast, head and neck squamous and hepatocellular carcinomas[66-69]. Importantly, we also detected aberrant activation of p38 in high grade CRC biopsies[77] and inflammatory bowel disease-associated human CRC specimens (Simone C, unpublished results).

Signaling networks are important to maintain genome stability during cell cycle to protect cells from tumorigenesis. Besides, additional control mechanisms include cell death and autophagy.

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved catabolic process regulating turn over and elimination of proteins, cellular organelles, such as peroxisomes, ribosomes and mitochondria, and the endoplasmic reticulum. The resulting metabolites are recycled for biosynthesis and energy metabolism. This process includes the formation of double-membrane cytosolic vesicles, termed autophagosomes, which then fuse with endosomes and lysosomes to form autolysosomes, wherein degradation finally occurs. Like apoptosis, autophagy has emerged as a key process in physiologic cell response. It is constitutively active at low levels, but can be robustly activated under metabolic stress[78,79].

Complex connections exist between autophagy, apoptosis and cellular homeostasis; indeed, autophagy can act both as a protector and an executioner. The general view is that autophagy is a survival pathway; however, autophagy induction by prolonged starvation and other stresses can result in cell death[78,79]. The ability of autophagy to regulate cell death makes it a target in several diseases, such as cancer and neurodegenerative disorders[80].

Beclin-1/Atg6 has a central role in autophagy by interacting with the ‘‘nucleation step’’ kinase class III PI3K (Vps34) and with the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2/Bcl-xL. Beclin-1 can be released from Bcl-2/Bcl-xL complexes by pro-apoptotic BH3 proteins to trigger autophagy; however, Bax and Bak (pro-apoptotic proteins) can also be released from these complexes to trigger apoptosis[81]. Mice lacking beclin-1 or genes that play an important role in the autophagy machinery show increased tumorigenesis[80,82]. Autophagy appears deregulated during carcinogenesis and it is an important barrier for cellular transformation. However, autophagy has a two-faced role, which depends on the balance between cytoprotective and potentially oncogenic effects vs cell-death-promoting and tumor-suppressive effects[83]. Noticeably, autophagy can support tumor progression by contributing to tumor dormancy[84]. In mouse hepatocellular carcinoma cells, dormancy is regulated by the activity ratio between ERK and p38 MAPK[85].

Our group has previously reported that p38α is required for CRC cell proliferation and survival and that its genetic depletion or the pharmacological blockade of its kinase activity induces growth arrest, autophagy and cell death in a cell type-specific manner[21,86,87]. Interestingly, in these cells inhibition of the autophagic activity promoted a dramatic increase in cell death by inducing a molecular switch from autophagic to apoptotic cell death in CRC cells[21]. Moreover, p38α blockade interfered with the signal-dependent transcription of a subset of genes involved in cell cycle control, autophagy and cell death[21,71]. Our results indicate that the autophagy response to p38α blockade initially represents a survival pathway, while prolonged inactivation of the kinase leads to cell death. Indeed, reactivation of p38α induces a significant reduction of autophagic markers together with a slow reentry into the cell cycle[21,88].

Further evidence supporting the role of p38α as a negative regulator of autophagy comes from studies showing that manipulation of p38-interacting protein and p38α alters the localization of mATG9, a protein required for autophagosome formation. p38α mediates starvation-induced mATG9 trafficking to form autophagosomes, suggesting that p38α could provide the link to nutrient-dependent signaling cascades activated during autophagy[89]. The role of p38 signaling in the negative control of autophagy has also been described in hepatocytes under hypo-osmotic stress or upon addition of amino acids or insulin[90], and in cultured Sertoli cells treated with SB203580, a p38 specific inhibitor, which show accumulation of large autophagolysosomes[91]. Moreover, Keil et al[92] demonstrated that Atg5, an E3 ubiquitin ligase required for autophagosome elongation and LC3 lipidation, is phosphorylated by p38α and that regulation of p38α by GADD45/MEKK4 negatively modulates the autophagic process.

Despite the profound differences in the metabolism of normal and cancer cells, in both the activity of the autophagic machinery strongly depends on cell metabolic status[93]. An altered cellular metabolism is a common feature of cancer cells. Indeed, cancer cells predominantly produce energy by high rates of glycolysis, even in the presence of high oxygen tension, rather than by comparatively low rates of glycolysis followed by oxidation of pyruvate in mitochondria, as in most normal cells[94]. Cancer cells predominantly produce ATP through constitutive activation of aerobic glycolysis (50% of their ATP is obtained through the glycolytic flux, vs 10% observed in normal cells), a process that generally relies on the stabilization and activation of the transcription factor HIF1α, which regulates the expression of the glucose transporter GLUT1, the rate-limiting enzymes HK1/2 and PKM2, and LDHA, the enzyme responsible for the conversion of pyruvate into lactate. As such, HIF1α links aerobic glycolysis to carcinogenesis, representing one of the crossroads for tumor suppressor and oncogenic pathways[95,96].

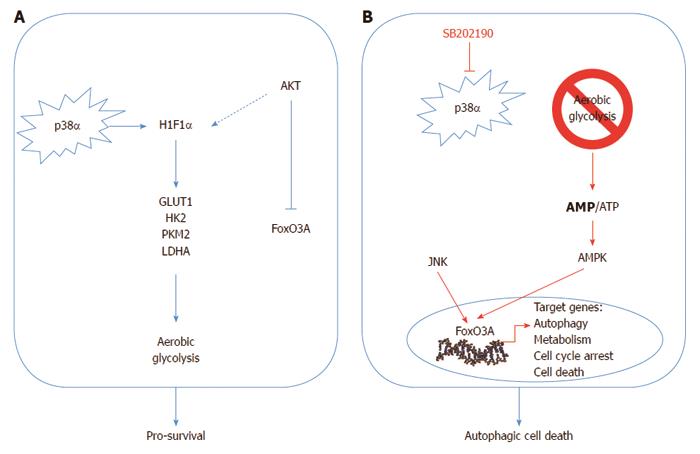

p38α is required to sustain HIF1α protein levels and the expression of its target genes; thus, its inhibition causes a rapid drop in ATP levels in CRC cells. This acute energy need triggers AMPK-dependent nuclear accumulation of FoxO3A and subsequent activation of its transcriptional program, leading to sequential induction of autophagy, cell cycle arrest and cell death. In vivo, pharmacological blockade of p38α has both a cytostatic and cytotoxic effect on colorectal neoplasms, and is associated with nuclear enrichment of FoxO3A and expression of its target genes p21 and PTEN[88].

The signaling perturbation imposed by p38α inhibition in CRC involves a reduction of S473 Akt phospho-activation together with the enrichment of the PTEN phosphatase, a pattern that correlates with the decreased Akt-dependent phospho-inhibition of FoxO3A on the T32 and S253 residues. Conversely, JNK, a potent activator of FoxO3A, was significantly phospho-activated in SB202190-treated CRC cell lines[88]. Importantly, PI3K class I enzymes negatively regulate autophagy in several cellular systems including CRC cells, and the JNK pathway has also been reported to be required for starvation-induced autophagy in cancer cells and for autophagic cell death[97,98]. Of note, PI3K/Akt and JNK can also crosstalk with p38α by cooperating at the chromatin level, and Akt can be activated by p38α/β through MAPK/APK2-dependent phosphorylation of serine 473[99]. Conversely, the antagonism between JNK and p38α signaling has been shown in different ways, including direct repression of the JNK upstream kinases Grap2/HPK1 and MKK7[47,100] (Figure 1).

It is now widely accepted that the MEK/ERK pathway plays a significant role in CRC formation and progression and that the kinase pathway including RAS, RAF, MEK 1/2, and ERK 1/2 is activated in most human tumors. Mutations in BRAF and KRAS oncogenes occur in 36% of all human cancers, including 15% of colorectal cancers and 40% of melanomas[101]. Haigis et al[102] demonstrated that KRAS affects proliferation and differentiation, whereas activated NRAS (a protein of the RAS family) suppresses apoptosis. However, although initial results demonstrated that inhibition of RAF or MEK1 exerts a cytostatic and cytotoxic effect in CRC cells in vitro and in xenograft models[103,104], the MEK1 inhibitor CI-1040 showed poor antitumor activity in phase II clinical trials[105].

Interestingly, it has been recently reported that ATP-competitive kinase inhibitors have potent antitumor effects on mutant BRAF tumors, with evidence of decreased tumor growth; in contrast, KRAS mutant tumors showed an opposite mechanism, with enhanced tumor growth in xenograft models[106]. Additionally, Corcoran et al[107] demonstrated that BRAF-mutant CRC cells were less sensitive to vemurafenib (RAF inhibitor) and displayed incomplete pospho-ERK suppression. They observed a rapid ERK reactivation occurring through EGFR-mediated activation of RAS and CRAS. Taken together, these findings support the idea that RAF and MEK inhibitors might be used depending on the cellular context and in combination with other therapeutic drugs.

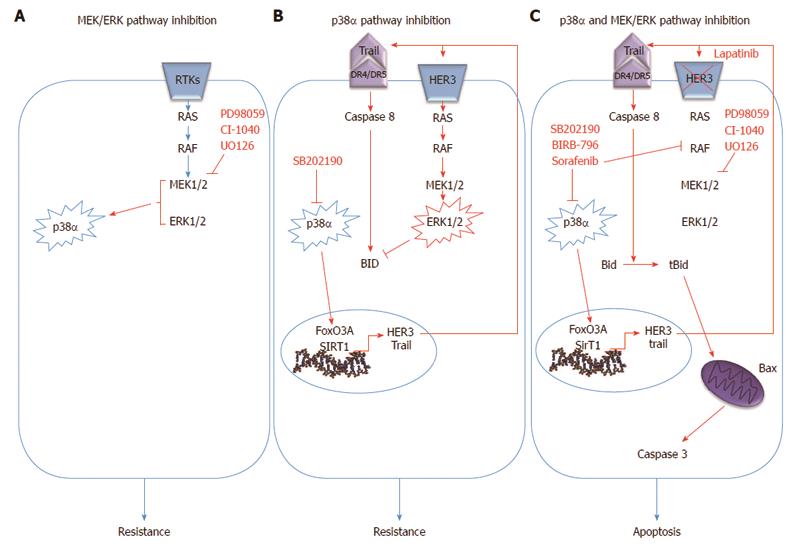

Recently, we showed that the crosstalk between the p38α and ERK pathway is crucial for CRC therapy response. Indeed, p38α inhibition by SB202190 up-regulates HER3, one of the receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK) of the EGF pathway, in CRC and this effect is dependent upon the activity of FoxO3A and its cofactor Sirt1[108]. This observation was also confirmed by using a structurally and functionally different p38α inhibitor, BIRB796, which is in phase III clinical trials for the treatment of inflammation[109]. In turn, HER3 up-regulation leads to overactivation of the MEK/ERK pathway, even in the presence of mutated RAF or RAS which are still able to over-activate ERK signaling in response to extracellular ligands (i.e., EGF)[110]. Of note, in breast cancer cells FoxO3A is able to increase expression of RTKs, including HER3, in response to AKT inhibition[111], and the phosphatase PP2A mediates the interplay between the p38α and the MEK/ERK pathways in primary fibroblasts and breast epithelial cells[112,113].

Activation of the MEK/ERK pathway in CRC cells upon p38α inhibition leads to the rescue of a pro-apoptotic program driven by the extrinsic pathway through transcriptional up-regulation of TRAIL and activation of caspase-8. Concomitant MEK inhibition triggers Bax-dependent apoptosis by enabling signaling propagation through t-Bid and caspase 3. Of note, recent research showed that the MEK/ERK pathway might affect Bid processing by caspase-8, thus resembling the activity of casein kinases I/II, which regulate caspase 8-dependent Bid cleavage by phosphorylation[114]. Bid phosphorylation at MAPK phosphorylation sites was induced by p38α inhibition and abrogated by concomitant inhibition of MEK1. Interestingly, the therapeutic efficacy of p38α/MEK1 inhibition in CRC is independent from mutations in p53, KRAS and BRAF genes, and from the CIN or MIN phenotype; conversely, Bax-/- cells showed almost 50% apoptosis reduction with respect to wild type cells. Combined inhibition of p38α and MEK1 efficiently reduces the volume of xenografted tumors and AOM/DSS-induced tumors in vivo[77].

Intriguingly, we observed p38α activation in HT-29, HCT-116 and Caco2 CRC cells treated with MEK1 inhibitors, a phenomenon that does not occur in human primary non-tumorigenic colon cells (Grossi V, Peserico A and Simone C, unpublished results), suggesting that a reciprocal compensatory role of these two pathways may exist in cancer cells. Indeed, inhibition of ERK activity triggers p38 activation also in cervical carcinoma HeLa cells[115].

Sorafenib, an experimental antitumor agent, potently inhibits nine protein kinases, including BRAF. It has also been shown to target the DFG-out conformational state of p38α and to affect p38α kinase activity in vitro[116,117]. Sorafenib induces apoptosis by down-regulating Mcl-1 in several cell lines and xenografted tumors, including HT-29 and HCT-116 CRC cells[116,118,119]. It has been approved for clinical use by the FDA in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and renal cell carcinoma (RCC), but failed to prove efficacy in CRC clinical trials[116,120]. Sorafenib, which is a type-II kinase inhibitor, has been tested in our lab in association with the type-I inhibitor SB202190 in CRC cell lines and animal models to investigate whether combination of these compounds may entail enhanced effects allowing to control more efficiently cancer cell growth[121]. Simultaneous inhibition of p38α DFG-in and -out conformations and BRAF leads to a synergistic increase of the apoptotic response in CRC cells, the most suitable type of cell death in tumor treatment. These observations are consistent with structural data and other studies showing that the DFG-in and DFG-out conformations of p38α can be targeted by type-I and type-II kinase inhibitors, respectively[117,122,123]. In fact, since sorafenib is able to bind to p38α, the residual kinase activity exerted by the remaining pool of p38α in the DFG-in conformation may constitute the basis of sorafenib clinical failure in CRC. Therefore, concomitant inhibition with a type-I inhibitor such as SB202190 is expected to abrogate the residual activity of p38α with consequent synergistic effects[121]. For these reasons, it is important to create the basis for a novel drug design paradigm of kinase inhibition, in which both the DFG-in and DFG-out conformations are simultaneously targeted, either with a combination of inhibitors (type-I and type-II inhibitors) or with one single agent acting against both conformations[124].

A recent report presented the latest clinical results about the multikinase inhibitor Regorafenib (Fluoro-Sorafenib), that targets, among others, RAF, wild type BRAF and mutated BRAF, and showed a particularly high inhibitory activity on p38 MAPK[125]. When administrated sequentially with standard chemotherapy, it displayed a good tolerance and a promising activity in patients with CRC. Currently, Regorafenib is being evaluated in phase II clinical trials in combination with FOLFOX6 and FOLFIRI in patients with mutant KRAS or BRAF CRC[125,126] and is now proposed for an international phase III clinical trial for the treatment of patients with metastatic CRC who have progressed after standard therapies (Figure 2).

Cancer cells can develop chemoresistance in the course of chemotherapy due to signaling pathways that have been altered during tumorigenesis. Following drug exposure, some clones within the cancer tissue can reprogram the expression of a specific set of genes leading to overactive and/or suppressed signaling networks. These adaptive changes may ultimately favor survival by desensitizing cells to drug-induced death signals. Due to this mechanism, patients might suffer from recurrent tumors originated from resistant clones[127-130].

The occurrence of chemoresistance is responsible for the limited success of various drugs in many cancers. For example, cisplatin, a chemotherapeutic agent frequently used against colorectal tumors, has been shown to induce cell death rates of up to 70% in the first phase of therapy; however, over time this rate gradually decreases to 15% due to the existence of unresponsive (chemoresistant) cells during chronic chemotherapy exposure[4,131,132].

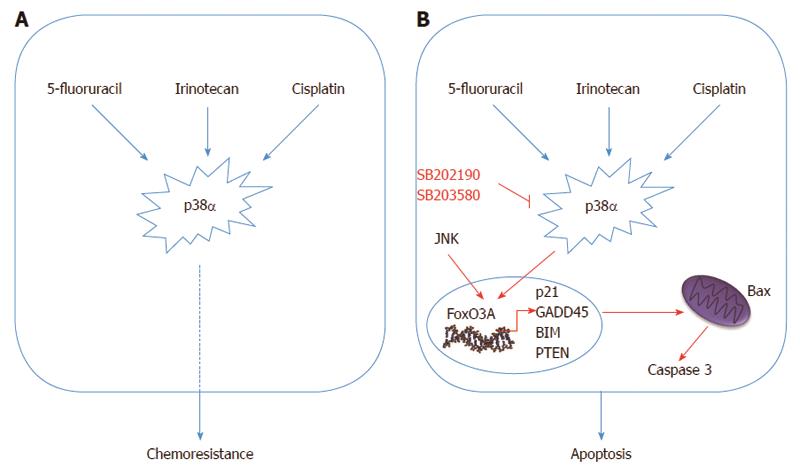

Thus, studies focusing on specific resistance mechanisms with the aim of finding new therapeutic strategies directed against specific targets have become increasingly desirable to improve patient survival. p38α might well be one of these targets. Indeed, response to cisplatin treatment is potentiated upon p38α inhibition, resulting in ROS-dependent upregulation of the JNK pathway in cancer cells, including CRC. In vivo, p38α inhibition cooperates with cisplatin treatment to reduce the size and malignancy of xenografted breast tumors in mice[133]. Additionally, we recently showed that p38α signaling is activated in cisplatin-treated CRC cells, and that p38α genetic ablation or pharmacological blockade sensitizes chemoresistant CRC cells to cisplatin. Furthermore, p38α inhibitors showed an additive effect with cisplatin in chemosensitive CRC cells, and co-treatment induced Bax-dependent apoptosis in both sensitive and resistant cells in vitro and in xenografted mouse models[134].

Chemoresistant cells may either show specific resistance to a particular drug or display multidrug resistance. P-glycoprotein (P-gp) is a well-established plasma membrane transporter which is involved in the efflux of chemotherapeutic agents by pumping drugs like cisplatin, vincristine and doxorubicin outside of cancer cells. When high p38 activity is observed in chemoresistant cells, P-gp expression is often upregulated and chemoresistance can be reversed by SB203580 treatment[135,136]. Using p38 inhibitors together with common chemotherapeutics has also given promising results in different experimental setups. Co-treatment with SB202190 and the chemotherapy drug irinotecan appears to sensitize chemoresistant CRC cells to chemotherapy thus supporting an important role for p38 in controlling chemoresistance[137,138]. SCIO-469 has been shown to reduce tumor growth in multiple myeloma xenograft tumors and to enhance the effect of bortezomib by inhibiting p38α. Additionally, VWCS, a peptide inhibitor, has been recently proposed both as a specific p38α inhibitor and a therapeutic agent[139-142]. In non-cancerous cells, p38 is involved in the inhibition of caspase 3, 8 and 9 activity in different conditions[143,144]. Similarly, CRC cells treated with SB202190 or SB203580 together with 5-fluorouracil showed increased caspase activity and sensitivity to chemotherapy due to increased Bax expression[145].

At the molecular level, chemoresistant cells within a CRC tissue may show different characteristics compared to their drug-sensitive parental cells; namely, increased expression of specific anti-apoptotic genes (e.g., BCL2, BCL2L1 and MCL1) has been often detected in chemoresistant clones[146,147]. Expression of these anti-apoptotic genes is regulated by various upstream molecules; still, Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL upregulation upon DNA damage has been found to take place in a p38-dependent way in human cervical cancer cells[148]. The requirement of p38 in Bcl-2-dependent apoptosis inhibition after DNA damage has also been reported in E1A/Ras-transformed fibroblasts[149]. Furthermore, inhibition of p38 by SB203580 appears to block hypoxia-induced Bcl-2 upregulation in endothelial cells, whereas inhibition of related pathways (PKC, ERK1/2 or PI3K) does not affect Bcl-2 expression[150].

Cyclooxygenase-2 (Cox-2), a downstream protein of p38α, is frequently found upregulated in response to several chemotherapeutics and its inhibition by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is thought to reduce the risk of CRC development by inducing cell death in adenomas[151,152]. Since Cox-2 activity is also associated with p38 activation, its upregulation has been shown to be reduced in SB203580-treated CRC cells, resulting in increased apoptosis in response to ursolic acid[153]. These studies show that chemoresistant CRC cells may induce a p38-mediated resistance mechanism to support survival or to delay the ongoing cell death processes. Inhibition of p38 by SB203580 has also been reported as an effective sensitizer reducing cell migration/invasion and enhancing sensitivity to etoposide treatment through Cox-2 downregulation in neuroblastomas[154].

Due to correlation with metastatic potential, cell migration in advanced tumors is another important issue to overcome in cancer therapy. p38α acts as a potent inducer of tumor invasion by regulating matrix metalloproteinases (MMP1, MMP3 and MMP13) in metastatic cancer cells[155]. TGFβ, which contributes to tumor progression and cell migration, acts through the p38 MAPK pathway, and p38 activity is required for TGFβ-mediated migration[67]. Death receptor-3-mediated p38 activation is required to promote survival and migration of CRC cells, and SB202190 treatment was found to decrease metastasis in in vivo breast cancer models[156,157]. These studies indicate that the p38 MAPK pathway is also involved in metastasis and affects cancer cell behavior beyond chemoresistance in advanced cancers (Figure 3).

The current idea is that tumorigenesis requires deregulation of several cellular processes and acquisition of particular features: independence from proliferation signals, evasion of apoptosis, insensitivity to anti-growth signals, unlimited replicative potential and ability to invade, metastasize and sustain angiogenesis for nutrient supply[30]. In addition, cancer cells need to acquire drug resistance and avoid oncogene-induced senescence[158]. In recent years, an emerging role has also been established for a subclass of neoplastic cells within tumors, termed cancer stem cells (CSCs)[30]. Importantly, CSCs show similar characteristics to normal intestinal stem cells, from which they are believed to originate. They are thought to be responsible for cancer relapse and to contribute to tumor chemoresistance. Recent reports identified the p38-Hsp27 axis as a survival pathway in hypoxic and serum-starved colorectal CSCs[159]. Moreover, the p38-Hsp27 pathway has been shown to mediate CSCs drug resistance to cisplatin[160] and anti-angiogenic agents[161].

Although the association of p38α activation with pro-apoptotic functions has been studied for years, in this review we showed that there are a significant number of reports highlighting its involvement in cancer cell survival, proliferation and chemoresistance. Indeed, p38α is over-active in CRC cells and tissues and is required to maintain cancer-specific metabolism[87]. Combined use of p38α inhibitors (SB202190, SB203580, BIRB796) and autophagy inhibitors (3MA, bafilomycin), MEK inhibitors (PD98059, UO126, CI-1040), HER2 inhibitors (lapatinib), multikinase inhibitors (sorafenib) or chemotherapeutic agents (5-FU, irinotecan, cisplatin) significantly reduced CRC growth in vitro and in preclinical models by inducing a higher degree of apoptosis compared to each single treatment[21,71,77,121,134]. Thus, targeting p38α in CRC offers oncologists various options for combined therapies and personalized medicine approaches: p38α inhibitors may be used in association with autophagy inhibitors, with molecularly-targeted drugs directed against the EGF pathway and with conventional chemotherapy. Besides, the phosphorylation status of p38 MAPK might be used as a marker of resistance and a predictor of therapy response in CRC.

p38α blockade exerts its chemosensitizing effects through nuclear accumulation of the transcription factor FoxO3A and activation of its pro-apoptotic gene expression program. Besides being involved in the response to the above mentioned p38 inhibitors and to cisplatin, FoxO3A is also implicated in the cellular response to paclitaxel, doxorubicin, imatinib, PI3K-Akt inhibitors, EGFR/HER2 inhibitors, and ionizing radiation[162]. Elucidation of the cellular players involved in resistance to chemotherapy and sensitization to cell death is a key issue for improving the efficacy of anti-cancer strategies, since response to treatment is often compromised by the development of chemoresistance. In this light, the new role described for the p38-FoxO3A axis in chemoresistance might prove of high importance for the design of new therapeutic strategies for CRC in combination with the above mentioned drugs.

Bax is required for proper apoptosis induction in all the combined therapeutic applications involving p38α inhibitors described for CRC in this review. Thus, Bax status may also represent a predictive bio-marker for p38α-targeted therapy response. Retention of one Bax wild-type allele is still sufficient to transduce apoptotic signals, while inactivation of the second allele produces apoptosis resistance. Importantly, Bax inactivating mutations have been described in more than 50% of CRCs characterized by a MIN phenotype, however these only account for 10%-15% of all CRCs[163].

Several p38α inhibitors passed phase I clinical trials and are currently in phase II or III for inflammatory diseases and cancer[109,164]. Of note, LY2228820 dimesylate, a selective inhibitor of p38 MAPK, passed a human phase I study in patients with advanced cancer[165]. Thus, these agents could be available for future combined therapy with chemotherapeutic agents and molecularly targeted drugs. Still, it is important that further clinical trials are developed to investigate the incorporation of more effective combination chemotherapy regimens into the multimodality treatment of CRC.

We thank Dr. Francesco Paolo Jori for his helpful discussion during the preparation of the manuscript and editorial assistance.

P- Reviewer: Kuo HC, Il Kim T S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Kemp Z, Thirlwell C, Sieber O, Silver A, Tomlinson I. An update on the genetics of colorectal cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13 Spec No 2:R177-R185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhang ZG, Harstrick A, Rustum YM. Mechanisms of resistance to fluoropyrimidines. Semin Oncol. 1992;19:4-9. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Petrelli N, Douglass HO, Herrera L, Russell D, Stablein DM, Bruckner HW, Mayer RJ, Schinella R, Green MD, Muggia FM. The modulation of fluorouracil with leucovorin in metastatic colorectal carcinoma: a prospective randomized phase III trial. Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:1419-1426. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Rabik CA, Dolan ME. Molecular mechanisms of resistance and toxicity associated with platinating agents. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33:9-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1096] [Cited by in RCA: 1229] [Article Influence: 61.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Willett CG, Duda DG, di Tomaso E, Boucher Y, Ancukiewicz M, Sahani DV, Lahdenranta J, Chung DC, Fischman AJ, Lauwers GY. Efficacy, safety, and biomarkers of neoadjuvant bevacizumab, radiation therapy, and fluorouracil in rectal cancer: a multidisciplinary phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3020-3026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 409] [Cited by in RCA: 389] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kyriakis JM, Avruch J. Mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:807-869. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kyriakis JM, Avruch J. Mammalian MAPK signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation: a 10-year update. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:689-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 873] [Cited by in RCA: 1122] [Article Influence: 80.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Reményi A, Good MC, Bhattacharyya RP, Lim WA. The role of docking interactions in mediating signaling input, output, and discrimination in the yeast MAPK network. Mol Cell. 2005;20:951-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jacobs D, Glossip D, Xing H, Muslin AJ, Kornfeld K. Multiple docking sites on substrate proteins form a modular system that mediates recognition by ERK MAP kinase. Genes Dev. 1999;13:163-175. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Biondi RM, Nebreda AR. Signalling specificity of Ser/Thr protein kinases through docking-site-mediated interactions. Biochem J. 2003;372:1-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rouse J, Cohen P, Trigon S, Morange M, Alonso-Llamazares A, Zamanillo D, Hunt T, Nebreda AR. A novel kinase cascade triggered by stress and heat shock that stimulates MAPKAP kinase-2 and phosphorylation of the small heat shock proteins. Cell. 1994;78:1027-1037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1295] [Cited by in RCA: 1331] [Article Influence: 41.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Han SJ, Choi KY, Brey PT, Lee WJ. Molecular cloning and characterization of a Drosophila p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:369-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shiozaki K, Russell P. Cell-cycle control linked to extracellular environment by MAP kinase pathway in fission yeast. Nature. 1995;378:739-743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 374] [Cited by in RCA: 377] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Brewster JL, de Valoir T, Dwyer ND, Winter E, Gustin MC. An osmosensing signal transduction pathway in yeast. Science. 1993;259:1760-1763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 944] [Cited by in RCA: 959] [Article Influence: 29.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shiozaki K, Russell P. Conjugation, meiosis, and the osmotic stress response are regulated by Spc1 kinase through Atf1 transcription factor in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2276-2288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 341] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wagner EF, Nebreda AR. Signal integration by JNK and p38 MAPK pathways in cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:537-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1708] [Cited by in RCA: 2037] [Article Influence: 119.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chiacchiera F, Simone C. Signal-dependent regulation of gene expression as a target for cancer treatment: inhibiting p38alpha in colorectal tumors. Cancer Lett. 2008;265:16-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cuadrado A, Nebreda AR. Mechanisms and functions of p38 MAPK signalling. Biochem J. 2010;429:403-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1064] [Cited by in RCA: 1326] [Article Influence: 82.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cuenda A, Rousseau S. p38 MAP-kinases pathway regulation, function and role in human diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:1358-1375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1094] [Cited by in RCA: 1069] [Article Influence: 56.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Vachon PH, Harnois C, Grenier A, Dufour G, Bouchard V, Han J, Landry J, Beaulieu JF, Vézina A, Dydensborg AB. Differentiation state-selective roles of p38 isoforms in human intestinal epithelial cell anoikis. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1980-1991. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Comes F, Matrone A, Lastella P, Nico B, Susca FC, Bagnulo R, Ingravallo G, Modica S, Lo Sasso G, Moschetta A. A novel cell type-specific role of p38alpha in the control of autophagy and cell death in colorectal cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:693-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lee JC, Laydon JT, McDonnell PC, Gallagher TF, Kumar S, Green D, McNulty D, Blumenthal MJ, Heys JR, Landvatter SW. A protein kinase involved in the regulation of inflammatory cytokine biosynthesis. Nature. 1994;372:739-746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2614] [Cited by in RCA: 2666] [Article Influence: 83.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 23. | Sanz V, Arozarena I, Crespo P. Distinct carboxy- termini confer divergent characteristics to the mitogen-activated protein kinase p38α and its splice isoform Mxi2. FEBS Lett. 2000;474:169-174. |

| 24. | Casar B, Sanz-Moreno V, Yazicioglu MN, Rodríguez J, Berciano MT, Lafarga M, Cobb MH, Crespo P. Mxi2 promotes stimulus-independent ERK nuclear translocation. EMBO J. 2007;26:635-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yagasaki Y, Sudo T, Osada H. Exip, a splicing variant of p38alpha, participates in interleukin-1 receptor proximal complex and downregulates NF-kappaB pathway. FEBS Lett. 2004;575:136-140. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Im JS, Lee JK. ATR-dependent activation of p38 MAP kinase is responsible for apoptotic cell death in cells depleted of Cdc7. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:25171-25177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Salvador JM, Mittelstadt PR, Belova GI, Fornace AJ, Ashwell JD. The autoimmune suppressor Gadd45alpha inhibits the T cell alternative p38 activation pathway. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:396-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zhang F, Strand A, Robbins D, Cobb MH, Goldsmith EJ. Atomic structure of the MAP kinase ERK2 at 2.3 A resolution. Nature. 1994;367:704-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 461] [Cited by in RCA: 478] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wilson KP, Fitzgibbon MJ, Caron PR, Griffith JP, Chen W, McCaffrey PG, Chambers SP, Su MS. Crystal structure of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27696-27700. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646-674. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Greenman C, Stephens P, Smith R, Dalgliesh GL, Hunter C, Bignell G, Davies H, Teague J, Butler A, Stevens C. Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature. 2007;446:153-158. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Wood LD, Parsons DW, Jones S, Lin J, Sjöblom T, Leary RJ, Shen D, Boca SM, Barber T, Ptak J. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2007;318:1108-1113. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Brozovic A, Osmak M. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by cisplatin and their role in cisplatin-resistance. Cancer Lett. 2007;251:1-16. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Ciesielski-Treska J, Ulrich G, Chasserot-Golaz S, Zwiller J, Revel MO, Aunis D, Bader MF. Mechanisms underlying neuronal death induced by chromogranin A-activated microglia. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13113-13120. [PubMed] |

| 35. | De Zutter GS, Davis RJ. Pro-apoptotic gene expression mediated by the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6168-6173. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Ghatan S, Larner S, Kinoshita Y, Hetman M, Patel L, Xia Z, Youle RJ, Morrison RS. p38 MAP kinase mediates bax translocation in nitric oxide-induced apoptosis in neurons. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:335-347. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Le-Niculescu H, Bonfoco E, Kasuya Y, Claret FX, Green DR, Karin M. Withdrawal of survival factors results in activation of the JNK pathway in neuronal cells leading to Fas ligand induction and cell death. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:751-763. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Mackay K, Mochly-Rosen D. An inhibitor of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase protects neonatal cardiac myocytes from ischemia. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:6272-6279. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Saurin AT, Martin JL, Heads RJ, Foley C, Mockridge JW, Wright MJ, Wang Y, Marber MS. The role of differential activation of p38-mitogen-activated protein kinase in preconditioned ventricular myocytes. FASEB J. 2000;14:2237-2246. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Wang Y, Huang S, Sah VP, Ross J, Brown JH, Han J, Chien KR. Cardiac muscle cell hypertrophy and apoptosis induced by distinct members of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase family. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2161-2168. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Valladares A, Alvarez AM, Ventura JJ, Roncero C, Benito M, Porras A. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase mediates tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced apoptosis in rat fetal brown adipocytes. Endocrinology. 2000;141:4383-4395. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Edlund S, Bu S, Schuster N, Aspenström P, Heuchel R, Heldin NE, ten Dijke P, Heldin CH, Landström M. Transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-beta)-induced apoptosis of prostate cancer cells involves Smad7-dependent activation of p38 by TGF-beta-activated kinase 1 and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 3. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:529-544. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Zhuang S, Demirs JT, Kochevar IE. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase mediates bid cleavage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and caspase-3 activation during apoptosis induced by singlet oxygen but not by hydrogen peroxide. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25939-25948. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Porras A, Zuluaga S, Black E, Valladares A, Alvarez AM, Ambrosino C, Benito M, Nebreda AR. P38 alpha mitogen-activated protein kinase sensitizes cells to apoptosis induced by different stimuli. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:922-933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Zuluaga S, Alvarez-Barrientos A, Gutiérrez-Uzquiza A, Benito M, Nebreda AR, Porras A. Negative regulation of Akt activity by p38alpha MAP kinase in cardiomyocytes involves membrane localization of PP2A through interaction with caveolin-1. Cell Signal. 2007;19:62-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Nebreda AR, Porras A. p38 MAP kinases: beyond the stress response. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:257-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 419] [Cited by in RCA: 439] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Ventura JJ, Tenbaum S, Perdiguero E, Huth M, Guerra C, Barbacid M, Pasparakis M, Nebreda AR. p38alpha MAP kinase is essential in lung stem and progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation. Nat Genet. 2007;39:750-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 249] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Brancho D, Tanaka N, Jaeschke A, Ventura JJ, Kelkar N, Tanaka Y, Kyuuma M, Takeshita T, Flavell RA, Davis RJ. Mechanism of p38 MAP kinase activation in vivo. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1969-1978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 395] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Bulavin DV, Phillips C, Nannenga B, Timofeev O, Donehower LA, Anderson CW, Appella E, Fornace AJ. Inactivation of the Wip1 phosphatase inhibits mammary tumorigenesis through p38 MAPK-mediated activation of the p16(Ink4a)-p19(Arf) pathway. Nat Genet. 2004;36:343-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 321] [Cited by in RCA: 343] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Tront JS, Hoffman B, Liebermann DA. Gadd45a suppresses Ras-driven mammary tumorigenesis by activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase and p38 stress signaling resulting in apoptosis and senescence. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8448-8454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Bulavin DV, Demidov ON, Saito S, Kauraniemi P, Phillips C, Amundson SA, Ambrosino C, Sauter G, Nebreda AR, Anderson CW, Kallioniemi A, Fornace AJ, Appella E. Amplification of PPM1D in human tumors abrogates p53 tumor-suppressor activity. Nat Genet. 2002;31:210-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 334] [Cited by in RCA: 346] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Li J, Yang Y, Peng Y, Austin RJ, van Eyndhoven WG, Nguyen KC, Gabriele T, McCurrach ME, Marks JR, Hoey T. Oncogenic properties of PPM1D located within a breast cancer amplification epicenter at 17q23. Nat Genet. 2002;31:133-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Yu W, Imoto I, Inoue J, Onda M, Emi M, Inazawa J. A novel amplification target, DUSP26, promotes anaplastic thyroid cancer cell growth by inhibiting p38 MAPK activity. Oncogene. 2007;26:1178-1187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Li SP, Junttila MR, Han J, Kähäri VM, Westermarck J. p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway suppresses cell survival by inducing dephosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase1,2. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3473-3477. [PubMed] |

| 55. | Wang W, Chen JX, Liao R, Deng Q, Zhou JJ, Huang S, Sun P. Sequential activation of the MEK-extracellular signal-regulated kinase and MKK3/6-p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediates oncogenic ras-induced premature senescence. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3389-3403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 305] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Nicke B, Bastien J, Khanna SJ, Warne PH, Cowling V, Cook SJ, Peters G, Delpuech O, Schulze A, Berns K. Involvement of MINK, a Ste20 family kinase, in Ras oncogene-induced growth arrest in human ovarian surface epithelial cells. Mol Cell. 2005;20:673-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Wolfman JC, Palmby T, Der CJ, Wolfman A. Cellular N-Ras promotes cell survival by downregulation of Jun N-terminal protein kinase and p38. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1589-1606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Qi X, Tang J, Pramanik R, Schultz RM, Shirasawa S, Sasazuki T, Han J, Chen G. p38 MAPK activation selectively induces cell death in K-ras-mutated human colon cancer cells through regulation of vitamin D receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22138-22144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Dolado I, Swat A, Ajenjo N, De Vita G, Cuadrado A, Nebreda AR. p38alpha MAP kinase as a sensor of reactive oxygen species in tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:191-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 316] [Cited by in RCA: 323] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Hui L, Bakiri L, Mairhorfer A, Schweifer N, Haslinger C, Kenner L, Komnenovic V, Scheuch H, Beug H, Wagner EF. p38alpha suppresses normal and cancer cell proliferation by antagonizing the JNK-c-Jun pathway. Nat Genet. 2007;39:741-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 301] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Voisset E, Oeztuerk-Winder F, Ruiz EJ, Ventura JJ. p38α negatively regulates survival and malignant selection of transformed bronchioalveolar stem cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Esteva FJ, Sahin AA, Smith TL, Yang Y, Pusztai L, Nahta R, Buchholz TA, Buzdar AU, Hortobagyi GN, Bacus SS. Prognostic significance of phosphorylated P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and HER-2 expression in lymph node-positive breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;100:499-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Wang SN, Lee KT, Tsai CJ, Chen YJ, Yeh YT. Phosphorylated p38 and JNK MAPK proteins in hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Clin Invest. 2012;42:1295-1301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Matrone A, Grossi V, Chiacchiera F, Fina E, Cappellari M, Caringella AM, Di Naro E, Loverro G, Simone C. p38alpha is required for ovarian cancer cell metabolism and survival. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:203-211. [PubMed] |

| 65. | Grossi V, Simone C. Special Agents Hunting Down Women Silent Killer: The Emerging Role of the p38α Kinase. J Oncol. 2012;2012:382159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Junttila MR, Ala-aho R, Jokilehto T, Peltonen J, Kallajoki M, Grenman R, Jaakkola P, Westermarck J, Kähäri VM. p38α and p38δ mitogen-activated protein kinase isoforms regulate invasion and growth of head and neck squamous carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:5267-5279. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Bakin AV, Rinehart C, Tomlinson AK, Arteaga CL. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for TGFbeta-mediated fibroblastic transdifferentiation and cell migration. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3193-3206. [PubMed] |

| 68. | Hsieh YH, Wu TT, Huang CY, Hsieh YS, Hwang JM, Liu JY. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway is involved in protein kinase Calpha-regulated invasion in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4320-4327. [PubMed] |

| 69. | Kim MS, Lee EJ, Kim HR, Moon A. p38 kinase is a key signaling molecule for H-Ras-induced cell motility and invasive phenotype in human breast epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5454-5461. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Chen L, Mayer JA, Krisko TI, Speers CW, Wang T, Hilsenbeck SG, Brown PH. Inhibition of the p38 kinase suppresses the proliferation of human ER-negative breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8853-8861. [PubMed] |

| 71. | Chiacchiera F, Simone C. Inhibition of p38alpha unveils an AMPK-FoxO3A axis linking autophagy to cancer-specific metabolism. Autophagy. 2009;5:1030-1033. [PubMed] |

| 72. | Ricote M, García-Tuñón I, Bethencourt F, Fraile B, Onsurbe P, Paniagua R, Royuela M. The p38 transduction pathway in prostatic neoplasia. J Pathol. 2006;208:401-407. [PubMed] |

| 73. | Schindler EM, Hindes A, Gribben EL, Burns CJ, Yin Y, Lin MH, Owen RJ, Longmore GD, Kissling GE, Arthur JS. p38delta Mitogen-activated protein kinase is essential for skin tumor development in mice. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4648-4655. [PubMed] |

| 74. | Emerling BM, Platanias LC, Black E, Nebreda AR, Davis RJ, Chandel NS. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for hypoxia signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:4853-4862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Halawani D, Mondeh R, Stanton LA, Beier F. p38 MAP kinase signaling is necessary for rat chondrosarcoma cell proliferation. Oncogene. 2004;23:3726-3731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Adam AP, George A, Schewe D, Bragado P, Iglesias BV, Ranganathan AC, Kourtidis A, Conklin DS, Aguirre-Ghiso JA. Computational identification of a p38SAPK-regulated transcription factor network required for tumor cell quiescence. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5664-5672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Chiacchiera F, Grossi V, Cappellari M, Peserico A, Simonatto M, Germani A, Russo S, Moyer MP, Resta N, Murzilli S. Blocking p38/ERK crosstalk affects colorectal cancer growth by inducing apoptosis in vitro and in preclinical mouse models. Cancer Lett. 2012;324:98-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Kroemer G, Levine B. Autophagic cell death: the story of a misnomer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:1004-1010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1204] [Cited by in RCA: 1171] [Article Influence: 65.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Mizushima N. Autophagy: process and function. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2861-2873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2692] [Cited by in RCA: 3132] [Article Influence: 164.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5765] [Cited by in RCA: 5815] [Article Influence: 323.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (12)] |

| 81. | Adams JM, Cory S. The Bcl-2 apoptotic switch in cancer development and therapy. Oncogene. 2007;26:1324-1337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1641] [Cited by in RCA: 1617] [Article Influence: 85.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | White E, Lowe SW. Eating to exit: autophagy-enabled senescence revealed. Genes Dev. 2009;23:784-787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | White E, DiPaola RS. The double-edged sword of autophagy modulation in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5308-5316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 907] [Cited by in RCA: 919] [Article Influence: 54.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Mathew R, Karantza-Wadsworth V, White E. Role of autophagy in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:961-967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1483] [Cited by in RCA: 1474] [Article Influence: 77.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Ranganathan AC, Adam AP, Aguirre-Ghiso JA. Opposing roles of mitogenic and stress signaling pathways in the induction of cancer dormancy. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1799-1807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Simone C. Signal-dependent control of autophagy and cell death in colorectal cancer cell: the role of the p38 pathway. Autophagy. 2007;3:468-471. [PubMed] |

| 87. | Madia F, Grossi V, Peserico A, Simone C. Updates from the Intestinal Front Line: Autophagic Weapons against Inflammation and Cancer. Cells. 2012;1:535-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Chiacchiera F, Matrone A, Ferrari E, Ingravallo G, Lo Sasso G, Murzilli S, Petruzzelli M, Salvatore L, Moschetta A, Simone C. p38alpha blockade inhibits colorectal cancer growth in vivo by inducing a switch from HIF1alpha- to FoxO-dependent transcription. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:1203-1214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Webber JL, Tooze SA. Coordinated regulation of autophagy by p38alpha MAPK through mAtg9 and p38IP. EMBO J. 2010;29:27-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | vom Dahl S, Dombrowski F, Schmitt M, Schliess F, Pfeifer U, Häussinger D. Cell hydration controls autophagosome formation in rat liver in a microtubule-dependent way downstream from p38MAPK activation. Biochem J. 2001;354:31-36. [PubMed] |

| 91. | Corcelle E, Djerbi N, Mari M, Nebout M, Fiorini C, Fénichel P, Hofman P, Poujeol P, Mograbi B. Control of the autophagy maturation step by the MAPK ERK and p38: lessons from environmental carcinogens. Autophagy. 2007;3:57-59. [PubMed] |

| 92. | Keil E, Höcker R, Schuster M, Essmann F, Ueffing N, Hoffman B, Liebermann DA, Pfeffer K, Schulze-Osthoff K, Schmitz I. Phosphorylation of Atg5 by the Gadd45β-MEKK4-p38 pathway inhibits autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20:321-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Jin S, White E. Tumor suppression by autophagy through the management of metabolic stress. Autophagy. 2008;4:563-566. [PubMed] |

| 94. | Denko NC. Hypoxia, HIF1 and glucose metabolism in the solid tumour. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:705-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1203] [Cited by in RCA: 1334] [Article Influence: 74.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Kroemer G, Pouyssegur J. Tumor cell metabolism: cancer’s Achilles’ heel. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:472-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1553] [Cited by in RCA: 1739] [Article Influence: 96.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Minet E, Michel G, Mottet D, Raes M, Michiels C. Transduction pathways involved in Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 phosphorylation and activation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:847-855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Wei Y, Pattingre S, Sinha S, Bassik M, Levine B. JNK1-mediated phosphorylation of Bcl-2 regulates starvation-induced autophagy. Mol Cell. 2008;30:678-688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1087] [Cited by in RCA: 1121] [Article Influence: 62.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Yu L, Alva A, Su H, Dutt P, Freundt E, Welsh S, Baehrecke EH, Lenardo MJ. Regulation of an ATG7-beclin 1 program of autophagic cell death by caspase-8. Science. 2004;304:1500-1502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 949] [Cited by in RCA: 966] [Article Influence: 43.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Rane MJ, Coxon PY, Powell DW, Webster R, Klein JB, Pierce W, Ping P, McLeish KR. p38 Kinase-dependent MAPKAPK-2 activation functions as 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-2 for Akt in human neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3517-3523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Perdiguero E, Ruiz-Bonilla V, Serrano AL, Muñoz-Cánoves P. Genetic deficiency of p38alpha reveals its critical role in myoblast cell cycle exit: the p38alpha-JNK connection. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1298-1303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Waterston RH, Lindblad-Toh K, Birney E, Rogers J, Abril JF, Agarwal P, Agarwala R, Ainscough R, Alexandersson M, An P. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature. 2002;420:520-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4964] [Cited by in RCA: 5020] [Article Influence: 209.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Haigis KM, Kendall KR, Wang Y, Cheung A, Haigis MC, Glickman JN, Niwa-Kawakita M, Sweet-Cordero A, Sebolt-Leopold J, Shannon KM. Differential effects of oncogenic K-Ras and N-Ras on proliferation, differentiation and tumor progression in the colon. Nat Genet. 2008;40:600-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 497] [Cited by in RCA: 480] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 103. | Wang S, El-Deiry WS. TRAIL and apoptosis induction by TNF-family death receptors. Oncogene. 2003;22:8628-8633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 613] [Cited by in RCA: 666] [Article Influence: 29.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | De Robertis M, Massi E, Poeta ML, Carotti S, Morini S, Cecchetelli L, Signori E, Fazio VM. The AOM/DSS murine model for the study of colon carcinogenesis: From pathways to diagnosis and therapy studies. J Carcinog. 2011;10:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in RCA: 428] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23762] [Cited by in RCA: 25600] [Article Influence: 1706.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (10)] |

| 106. | Hatzivassiliou G, Song K, Yen I, Brandhuber BJ, Anderson DJ, Alvarado R, Ludlam MJ, Stokoe D, Gloor SL, Vigers G. RAF inhibitors prime wild-type RAF to activate the MAPK pathway and enhance growth. Nature. 2010;464:431-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1208] [Cited by in RCA: 1286] [Article Influence: 80.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Corcoran RB, Ebi H, Turke AB, Coffee EM, Nishino M, Cogdill AP, Brown RD, Della Pelle P, Dias-Santagata D, Hung KE. EGFR-mediated re-activation of MAPK signaling contributes to insensitivity of BRAF mutant colorectal cancers to RAF inhibition with vemurafenib. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:227-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 660] [Cited by in RCA: 840] [Article Influence: 60.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 108. | Brunet A, Sweeney LB, Sturgill JF, Chua KF, Greer PL, Lin Y, Tran H, Ross SE, Mostoslavsky R, Cohen HY. Stress-dependent regulation of FOXO transcription factors by the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science. 2004;303:2011-2015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2498] [Cited by in RCA: 2616] [Article Influence: 118.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 109. | Schreiber S, Feagan B, D’Haens G, Colombel JF, Geboes K, Yurcov M, Isakov V, Golovenko O, Bernstein CN, Ludwig D. Oral p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibition with BIRB 796 for active Crohn’s disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:325-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Pattingre S, Bauvy C, Codogno P. Amino acids interfere with the ERK1/2-dependent control of macroautophagy by controlling the activation of Raf-1 in human colon cancer HT-29 cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16667-16674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Chandarlapaty S, Sawai A, Scaltriti M, Rodrik-Outmezguine V, Grbovic-Huezo O, Serra V, Majumder PK, Baselga J, Rosen N. AKT inhibition relieves feedback suppression of receptor tyrosine kinase expression and activity. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:58-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 814] [Cited by in RCA: 812] [Article Influence: 54.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Wen HC, Avivar-Valderas A, Sosa MS, Girnius N, Farias EF, Davis RJ, Aguirre-Ghiso JA. p38α Signaling Induces Anoikis and Lumen Formation During Mammary Morphogenesis. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Junttila MR, Li SP, Westermarck J. Phosphatase-mediated crosstalk between MAPK signaling pathways in the regulation of cell survival. FASEB J. 2008;22:954-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 603] [Cited by in RCA: 642] [Article Influence: 33.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | Desagher S, Osen-Sand A, Montessuit S, Magnenat E, Vilbois F, Hochmann A, Journot L, Antonsson B, Martinou JC. Phosphorylation of bid by casein kinases I and II regulates its cleavage by caspase 8. Mol Cell. 2001;8:601-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 115. | Berra E, Diaz-Meco MT, Moscat J. The activation of p38 and apoptosis by the inhibition of Erk is antagonized by the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10792-10797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 116. | Wilhelm S, Carter C, Lynch M, Lowinger T, Dumas J, Smith RA, Schwartz B, Simantov R, Kelley S. Discovery and development of sorafenib: a multikinase inhibitor for treating cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:835-844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1230] [Cited by in RCA: 1391] [Article Influence: 69.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 117. | Namboodiri HV, Bukhtiyarova M, Ramcharan J, Karpusas M, Lee Y, Springman EB. Analysis of imatinib and sorafenib binding to p38alpha compared with c-Abl and b-Raf provides structural insights for understanding the selectivity of inhibitors targeting the DFG-out form of protein kinases. Biochemistry. 2010;49:3611-3618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 118. | Wilhelm SM, Carter C, Tang L, Wilkie D, McNabola A, Rong H, Chen C, Zhang X, Vincent P, McHugh M. BAY 43-9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral antitumor activity and targets the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases involved in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7099-7109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2966] [Cited by in RCA: 3186] [Article Influence: 144.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 119. | Wilhelm SM, Adnane L, Newell P, Villanueva A, Llovet JM, Lynch M. Preclinical overview of sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor that targets both Raf and VEGF and PDGF receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:3129-3140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1149] [Cited by in RCA: 1139] [Article Influence: 63.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 120. | Dal Lago L, D’Hondt V, Awada A. Selected combination therapy with sorafenib: a review of clinical data and perspectives in advanced solid tumors. Oncologist. 2008;13:845-858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 121. | Grossi V, Liuzzi M, Murzilli S, Martelli N, Napoli A, Ingravallo G, Del Rio A, Simone C. Sorafenib inhibits p38α activity in colorectal cancer cells and synergizes with the DFG-in inhibitor SB202190 to increase apoptotic response. Cancer Biol Ther. 2012;13:1471-1481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 122. | Filomia F, De Rienzo F, Menziani MC. Insights into MAPK p38alpha DFG flip mechanism by accelerated molecular dynamics. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:6805-6812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 123. | Kufareva I, Abagyan R. Type-II kinase inhibitor docking, screening, and profiling using modified structures of active kinase states. J Med Chem. 2008;51:7921-7932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 124. | Montagut C, Settleman J. Targeting the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway in cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2009;283:125-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 339] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 125. | Strumberg D, Schultheis B. Regorafenib for cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2012;21:879-889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 126. | Strumberg D, Scheulen ME, Schultheis B, Richly H, Frost A, Büchert M, Christensen O, Jeffers M, Heinig R, Boix O. Regorafenib (BAY 73-4506) in advanced colorectal cancer: a phase I study. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1722-1727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 127. | Benson VS, Patnick J, Davies AK, Nadel MR, Smith RA, Atkin WS. Colorectal cancer screening: a comparison of 35 initiatives in 17 countries. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:1357-1367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 128. | Katano K, Kondo A, Safaei R, Holzer A, Samimi G, Mishima M, Kuo YM, Rochdi M, Howell SB. Acquisition of resistance to cisplatin is accompanied by changes in the cellular pharmacology of copper. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6559-6565. [PubMed] |