Published online Jul 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i28.9592

Revised: February 9, 2014

Accepted: April 2, 2014

Published online: July 28, 2014

Processing time: 209 Days and 11.9 Hours

AIM: To analyze the potential relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and the development of atrial fibrillation (AF).

METHODS: Using the key words “atrial fibrillation and gastroesophageal reflux”, “atrial fibrillation and esophagitis, peptic”, “atrial fibrillation and hernia, hiatal” the PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, OVIDSP, WILEY databases were screened for relevant publications on GERD and AF in adults between January 1972-December 2013. Studies written in languages other than English or French, studies not performed in humans, reviews, case reports, abstracts, conference presentations, letters to the editor, editorials, comments and opinions were not taken into consideration. Articles treating the subject of radiofrequency ablation of AF and the consecutive development of GERD were also excluded.

RESULTS: Two thousand one hundred sixty-one titles were found of which 8 articles met the inclusion criteria. The presence of AF in patients with GERD was reported to be between 0.62%-14%, higher compared to those without GERD. Epidemiological data provided by these observational studies showed that patients with GERD, especially those with more severe GERD-related symptoms, had an increased risk of developing AF compared with those without GERD, but a causal relationship between GERD and AF could not be established based on these studies. The mechanisms of AF as a consequence of GERD remain largely unknown, with inflammation and vagal stimulation playing a possible role in the development of these disorders. Treatment with proton pomp inhibitors may improve symptoms related to AF and facilitate conversion to sinus rhythm.

CONCLUSION: Although links between AF and GERD exist, large randomized clinical studies are required for a better understanding of the relationship between these two entities.

Core tip: The link between gastroesophageal reflux disease and atrial fibrillation is currently not understood completely. A few papers from the literature address this issue, but none has been able to draw firm conclusions. This review of the literature analyzes the potential relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and the development of atrial fibrillation. Five electronic databases were screened for publications on gastroesophageal reflux disease and atrial fibrillation in adults and the 8 articles found are analyzed and discussed. Although evidence on atrial fibrillation associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease exists, large randomized clinical studies are required to provide definite answers.

- Citation: Roman C, Varannes SBD, Muresan L, Picos A, Dumitrascu DL. Atrial fibrillation in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease: A comprehensive review. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(28): 9592-9599

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i28/9592.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i28.9592

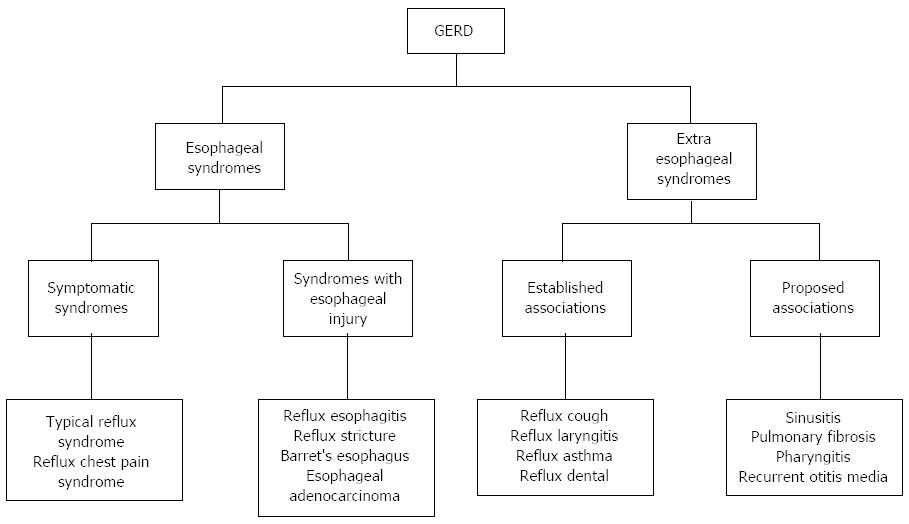

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is one of the most frequent gastrointestinal diseases encountered in outpatient clinics[1]. The prevalence of this condition is growing and its annual prevalence rate varies between 0.8% and 40% in different populations[2]. While in Western countries it is reported to be as high as 10%-15%[3], a lower prevalence of 5% has been reported in Asia. However, along with changes in diet and the increasing number of cases of obesity[4] and metabolic syndromes[5], the prevalence of GERD seems to be increasing in this part of the world. The prevalence of GERD is also increasing in children and adolescents, suggesting that the process may begin early in susceptible individuals. According to the Montreal consensus[6-8], GERD is defined as a condition which appears when the reflux from the stomach into the esophagus determines symptoms that disturb the patient and/or provokes complications. Clinically, the symptoms of GERD may be grouped in 2 syndromes: the esophageal syndrome (reflux chest pain syndrome, the typical reflux syndrome, reflux esophagitis, reflux stricture, Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma) and extra-esophageal manifestations (Figure 1). In affected patients, GERD impairs the health status and the quality of life[3,6]. The focus of specialists is directed mainly towards the esophageal and other digestive manifestations of the disease, the cardiovascular involvement in GERD being a less investigated aspect.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia encountered in clinical practice, with a prevalence of 1% in the general population. The prevalence of AF increases with age, reaching 10% in octogenarians. It impairs the quality of life (by causing a decrease in exercise capacity, an increased risk of developing heart failure and stroke) and increases mortality.

AF is frequently associated with other cardiovascular diseases, such as hypertension, ischemic heart disease, valvular heart disease, heart failure, cardiomyopathies, and diabetes. In 10%-15% of patients, a structural heart disease cannot be identified, the term for this case being “lone atrial fibrillation”[9]. Recently, several other factors that may be involved in the development of AF, such as: obesity, sleep apnea, alcohol abuse, latent hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, systemic and local inflammation have been described. According to some authors, other factors contributing to the initiation of AF may exist, but they currently remain unidentified[10-12].

The aim of this paper is to analyze the potential relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and the development of atrial fibrillation.

Using the key terms: “atrial fibrillation and gastroesophageal reflux”; “atrial fibrillation and esophagitis, peptic”; “atrial fibrillation and hernia, hiatal”, the PubMed EMBASE, Cochrane Library, WILEY, OVIDSP databases were searched for relevant publications on AF and GERD between January 1972-December 2013. Eligibility criteria for the studies included were: a minimum of 10 adult subjects with the diagnoses of GERD and AF; studies with case-control design, consecutive cases or selected cases regardless of prospective or retrospective design; studies that followed the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions on symptoms of GERD and AF. Finally, only papers available in full text were included in this review.

Studies not performed on humans, papers treating the subject of radiofrequency ablation of AF and the consecutive development of GERD, studies for which not even the abstract was available, abstracts or posters presented at various conferences and papers written in languages other than English or French were not taken into consideration. Duplicate titles and reviews were also excluded.

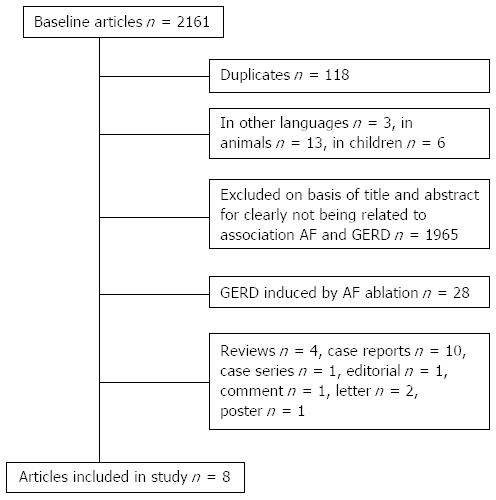

The search strategy returned a total of 2161 references (Figure 2) of the five electronic databases screened. After exclusion of duplicate or irrelevant references, 56 articles were retained for a more detailed analysis. Twenty eight articles assessed the presence of GERD after AF ablation and for this reason they were not taken into account. Another 4 publications were reviews, 10 were case reports, 1 case-series, 1 editorial, 1 comment and opinion, 2 letters to the editor and 1 poster, none of them meeting the inclusion criteria and were therefore excluded.

Of the 8 articles included in the present review, 5 studies were prospective, of which only one was a randomized study. A summary of study characteristics is presented in Table 1.

| Ref. | Type of study | Patients (n) | Diagnosis of GERD and AF | Conclusion |

| Weigl et al[14], 2003 | Retrospective | GERD and lone AF (n = 18) | Gastroscopy ECG | PPIs therapy could be beneficial in a subgroup of patients with AF, with fewer side effects |

| Cuomo et al[15], 2006 | Prospective, mechanistic | GERD and arrhythmias (n = 32) Control group (n = 9) | Upper endoscopy Simultaneous 24-h pH-meter and Holter monitoring | PPIs therapy seems to improve GERD and cardiac symptoms in dysrhythmic patients in whom esophageal acid stimulus induces cardiac autonomic reflexes |

| Bunch et al[16], 2008 | Prospective, epidemiologic, randomized | Olmsted County residents (n = 5288) | Self-report questionnaire Medical records ECG ICD-9 codes | There was no association between GERD and AF. Patients with esophagitis are more predisposed to develop AF |

| Kunz et al[17], 2009 | Retrospective, epidemiologic | n = 163627 | ICD-9 codes | GERD is associated with a higher risk of AF |

| Shimazu et al[18], 2011 | Retrospective | GERD and AF (n = 86) | Questionnaire F-scale ECG, Holter monitoring | AF is an independent risk factor for GERD |

| Huang et al[19], 2012 | Prospective, epidemiologic | GERD (n = 29688)Control group (n = 29597) | ICD-9 codes Endoscopy or 24-hs pH-meter ECG, Holter monitoring | Taken independently, GERD is associated with a higher risk of future AF in a nationwide population-based cohort |

| Reddy et al[21], 2013 | Prospective, matched, case-control, mechanistic | GERD and AF (n = 10) Control group (n = 30) | Symptoms questionnaire | Patients with GERD are more likely to have AF and a positive vagal response during radiofrequency catheter ablation |

| Kubota et al[22], 2013 | Cross-sectional | n = 201Control group (n = 278) | Questionnaire F-scale ECG, Holter monitoring | Significant correlation between nonvalvular AF and symptomatic GERD |

Epidemiological data provided by these observational studies showed that patients with GERD, especially those with more severe GERD-related symptoms, had an increased risk of developing AF compared with those without GERD, but a causal relationship between GERD and AF could not be established based on these studies.

GERD and AF are two diseases frequently encountered in clinical practice and their association is currently being investigated, as they share some common factors such as sleep apnea, obesity and diabetes. The relationship between gastrointestinal symptoms and arrhythmias was first described by Ludwig Roemheld, under the name of “Roemheld gastrocardiac syndrome”, in which an oesophago-gastric stimulus was able to induce arrhythmia-related symptoms[13].

Several observational studies have shown that GERD and especially esophagitis could determine and perpetuate paroxysmal AF. However, up to the present, the mechanism of AF as a consequence of gastroesophageal reflux remains unknown, with inflammation and vagal stimulation playing a possible role in the development of these disorders. These studies raise arguments regarding a possible reciprocal relationship between these two entities. Several studies have shown that proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) could represent an alternative to the standard antiarrhythmic treatment by improving symptoms related to AF and by facilitating conversion to sinus rhythm, with the advantage of being less expensive and with fewer side effects.

In 2003, Weigl et al[14] conducted a study on 89 patients with reflux esophagitis of which 18 (6 women, aged 39-69 years) had lone AF. The diagnosis of GERD was based on gastroscopy. Lone AF was defined if the patients had at least two episodes of AF alternating with sinus rhythm documented on electrocardiography within 3 mo before endoscopy. Patients with chronic AF were excluded. Once the patients were diagnosed with reflux esophagitis, they received PPIs therapy in standard doses for at least 2 mo. Under this treatment, both gastrointestinal and AF related symptoms improved in 14 patients (78%), these patients having a sinus rhythm on the electrocardiogram (ECG). In these patients, the doses of the antiarrhythmic drugs were not increased and there was no need for administering another one. Furthermore, in 5 patients antiarrhythmic drugs were interrupted. The conclusion of this study was that in a subset of patients with AF, adequate treatment of esophagitis could be beneficial, with fewer side effects than standard therapy. This study had several limitations, including the small group of patients investigated, the retrospective design, the absence of a control group and the impossibility to rule out the placebo effect.

In 2006, Cuomo et al[15] studied the relationship between the presence of acid reflux in the esophagus and neurocardiac function of patients with GERD and arrhythmias and the efficacy of PPIs on symptoms of GERD and arrhythmias. In this case-control study, 32 patients (13 females, mean age 47.0 ± 2.2 years) with GERD and arrhythmia-related symptoms, and 9 patients with GERD only (5 females, mean age 53.0 ± 2.0 years) were included. Validated questionnaires and endoscopy were used to establish the diagnosis of GERD. Holter ECG was performed for each patient, during esophageal manometry, acid perfusion and 24-h pH monitoring. For further evaluation of the relationship between acid reflux and neurocardiac function, a full dose of PPIs was administrated to all patients for 3 mo. The results showed that in 56% of patients with GERD and arrhythmias a statistically significant correlation between the esophageal pH and heart rate variability was achieved. PPIs therapy was also efficient in these patients with a significant reduction of cardiac symptoms (13/16 vs 4/11 of patients, P < 0.01). The authors concluded that in patients with GERD and arrhythmias, in whom esophageal acid stimulus induced cardiac autonomic reflexes, acid suppression seemed to improve both GERD and arrhythmia-related symptoms. The limitations of this study were the evaluation of cardiac symptoms with a simple questionnaire, without a thorough cardiologic assessment during and after PPIs treatment, and the lack of a control group treated with placebo.

In 2008, Bunch et al[16] published a prospective observational study on 5288 subjects conducted between 1988 and 1994, using a self-report questionnaire. Their aim was to assess the presence of GERD in this population and the long-term risk of developing AF. Diagnosis of AF was based on medical records, ECG database, and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9 codes). Of the total patients surveyed, 741 (14%) developed AF over a follow up period of approximately 11 years. Male gender, age, the presence of hypertension, congestive heart failure, and esophagitis were associated with the risk of developing AF. After adjustment for other risk factors (HR = 0.81, 95%CI: 0.68-0.96, P = 0.014), an inverse relationship between GERD and AF was found. A borderline statistical significance was obtained in patients with daily symptoms of GERD, vs patients with less frequent GERD-related symptoms. The presence of esophagitis increased the risk of AF, but this correlation was not present when other risk factors were taken into account (P = 0.72). However, patients with esophagitis were more likely to develop AF. The limitations of this study were the fact that the presence of GERD was assessed using a subjective tool (a self-report questionnaire), the diagnosis of AF being based upon ICD-9 codes, ECG database and medical records and thus possibly missing asymptomatic episodes of AF, and incomplete information provided about AF subtypes.

Two other retrospective studies performed recently, one in 2009 by Kunz et al[17] and the second by Shimazu et al[18] in 2011 have concluded that GERD is associated with an increased risk of developing AF. In the study conducted by Kunz et al[17], 163627 ambulatory patients from the National Capitol Area military health care system, were evaluated between January 2001 and October 2007. The diagnoses of GERD and AF were established using the ICD-9 codes. Of 163627 subjects, 7992 (5%) had AF. The results showed that GERD was associated with an increased risk of developing AF (RR: 1.39, 95%CI: 1.33-1.45). This relationship persisted (RR: 1.19, 95%CI: 1.13-1.25) after adjustment for other risk factors (age, male sex, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, smoking). In the study by Shimazu et al[18], 188 outpatients (78 females) with a mean age 60.4 ± 0.9 years were included. Patients were classified upon the frequency scale (F scale), a formulated questionnaire used in Japan, for identifying symptoms of GERD. Eighty six (46%) patients had AF, of which 25 had paroxysmal AF and 61 permanent AF. Two of 25 patients with paroxysmal AF and 10 of 61 patients with permanent AF showed valvular AF. Total scores on F-scale were significantly higher in patients with AF (87%) compared with those with lower scores (42%) (P = 0.019). The reflux and total score did not differ between patients with paroxysmal AF and permanent forms (P = 0.609,P = 0.677). The univariate analysis demonstrated a significant correlation between AF and GERD (P < 0.001). The main limitation of this study was that the questionnaire responses were not correlated with endoscopic findings and thus the pathophysiological relationship between these two entities could be erroneous.

In 2012, Huang et al[19] performed a prospective study on 29688 patients with GERD selected from a 1000000 person cohort dataset from the Taiwan National Health Insurance database. This group was compared with a control group which included 29597 subjects without history of GERD or arrhythmias. The patients with GERD were diagnosed using ICD-9 codes and the presence of AF was confirmed using the ICD-9-CM code, ECG and Holter monitors. Patients included in this study were followed up for three years. During this period, AF occurred in 184 (0.62%) of the patients with GERD and in 167 (0.56%) of the control group. Results showed that the incidence of AF was significantly higher in patients with GERD compared to those without GERD (P = 0.024). Taken independently, GERD was associated with a higher risk of AF (HR = 1.31; 95%CI: 1.06-1.61, P = 0.013). Furthermore, the investigators analyzed the impact of PPI therapy in patients with GERD and AF, and the results showed that the patients who received PPI therapy had an increased risk of developing AF (HR = 1.46; 95%CI: 1.15-1.86, P = 0.002). However, patients with GERD not treated with PPIs did not have an increased risk of AF. A possible explanation for this finding was the fact that patients who received PPIs had more severe GERD-related symptoms and the severity of the disease determined and increased risk of AF, not the administration of PPIs per se. Nevertheless, there are some concerns about the possible pro-arrhythmic effect of PPIs[20], which makes the interpretation of the results more difficult.

Recently, Reddy et al[21] studied the role of radiofrequency catheter ablation of AF in patients with GERD and/or irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). In this prospective, case-control matched study, 30 patients with AF and definitive clinical diagnosis of GERD and/or IBS and 30 patients with AF only were enrolled. All patients underwent the ablation procedure during which vagal response was evaluated (sinus bradycardia, asystole, atrioventricular block or hypotension). Pre- and post ablation, the patients were questioned about their gastrointestinal symptoms using a symptom-based questionnaire. The patients were followed up at 3, 6 and 12 mo. Compared to patients with AF only, patients with GERD and/or IBS had a positive vagal response during the AF ablation procedure (60% vs 13%, P < 0.001). A greater number of these patients had self-reported AF triggers (defecation, abdominal bloating, alcohol carbonated beverages, cold water and greasy food consumption) compared to the other group (20/67 vs 7/23%, P = 0.007). However, interpretation of these data must be proceeded with caution, due to the relatively small number of patients included, the observational nature of the study and the lack of evaluation of heart rate variability.

Another study, published in 2013 by Kubota et al[22], analyzed the relationship between nonvalvular AF and GERD in 201 outpatients and 278 participants of a community-based annual health screening program. For the diagnosis of GERD, the F-scale was used. Sixty one patients had permanent AF and 25 paroxysmal AF. The results showed that the incidence of GERD was significantly increased in patients with AF (P = 0.004). The multivariate analysis demonstrated that nonvalvular AF was an independent risk factor for symptomatic GERD (Wilks’ lambda = 0.983, P = 0.004). However, the patients included in the study lacked endoscopic examination and the follow up period was short.

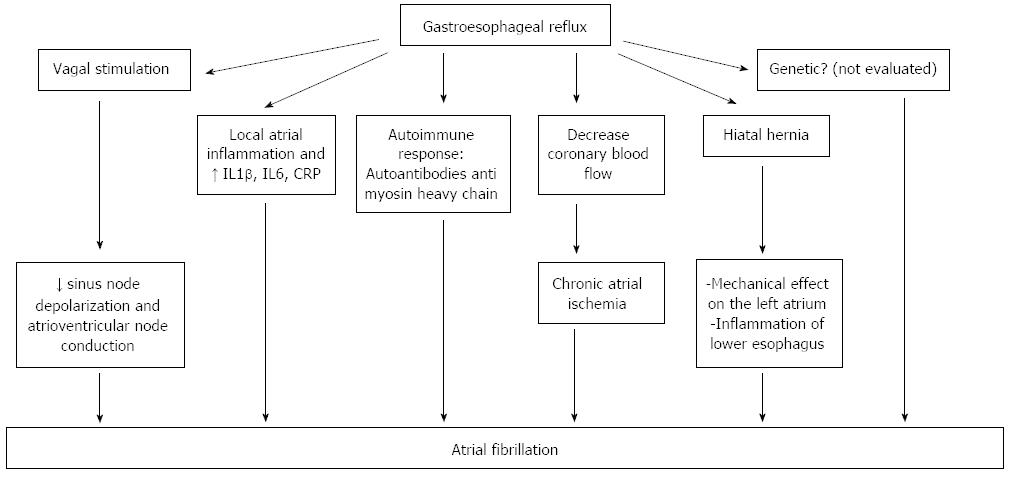

The mechanism by which esophageal reflux determines AF is currently unknown. The mechanisms which are presumably involved derive from several observational studies.

A number of studies draw attention on an imbalance of the autonomic nervous system that could initiate or maintain AF. In patients with structural heart diseases, often seen in elderly, the stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system initiates AF, while in young people, lone AF is more common, due to a higher parasympathetic system tone. This type of lone AF, vagally mediated, appears especially at night, during rest and postprandial. However, adrenergically mediated AF also exists, occurring during daytime, under stress and during exercise. Both types of lone AF may coexist in the same patient.

Heart rate variability analysis is an accurate and non-invasive method used for the evaluation of cardiac autonomic function[23], and the studies using this tool have shown that chemical, electrical and mechanical stimulation of the esophagus may modify the sympatho-vagal balance[24]. In a group of 28 patients with non-cardiac chest pain, using the Bernstein test, Tougas et al[25] demonstrated that only symptomatic patients (patients who experienced angina-like symptoms during acid infusion, also named acid sensitive patients), had an increased vagal tone. The esophageal acid reflux may induce vagal system overstimulation that could be a trigger of AF by slowing the sinus node depolarization rate and atrioventricular node conduction[26]. Swanson[27] showed that young athletes are more predisposed to experience AF, due to an increased vagal tone. Young subjects have an increased atrial vulnerability demonstrated in electrophysiological studies, which correlates with a shorter atrial effective refractory period[28]. Esophageal reflux is induced by exercise, increases with exercise intensity and duration and worsens postprandial or in a state of dehydration[27] (Figure 3).

Another mechanism that may explain the link between GERD and AF is the local atrial inflammation seen in patients with esophagitis, because of the proximity of the esophagus to the left atrium. Performing right atrial septal biopsies, Frustaci et al[29] demonstrated the presence of atrial lymphomononuclear infiltrates in 8 of 12 patients with lone atrial fibrillation. Esophageal reflux may also release inflammatory mediators such as IL1β, IL6[30] and highly sensitive C-reactive protein which correlates with the incidence[31], defibrillation efficacy[32], recurrence[33] and prognosis of AF[34]. These inflammatory mediators play an important role in the pathogenesis of AF[35,36].

Thirdly, GERD may induce an autoimmune response that may be implied in the pathogenesis of AF. In patients with lone AF, autoantibodies against myosin heavy chain have been detected[37].

Another hypothesis is that acid esophageal reflux may decrease coronary blood flow in patients with ischemic heart disease[38], thus causing chronic atrial ischemia which could be a trigger for initiation of AF[39].

Genetic factors may also play a role in the pathophysiology of lone AF, as recently suggested[40]. However, a link between genetic factors, gastroesophageal reflux and initiation of AF has not been studied so far.

Hiatal hernia may favor the occurrence of GERD or may aggravate pre-existing GERD in some patients. Atrial tachyarrhythmia associated with GERD was reported for the first time by Landmark et al[41] in 1979, but the mechanism by which hiatal hernia-GERD provokes arrhythmias has not yet been elucidated. There are two possible explanations: first, a large hiatal hernia may have a mechanical effect on the left atrium[42] compressing and irritating it. The second hypothesis is the presence of inflammation of the lower esophagus related to acid reflux favored by hiatal hernia.

The studies reviewed in this article have an intense inhomogeneity regarding inclusion criteria, study type (e.g., retrospective/prospective), choice of statistical analysis method (Cox regression, Fisher exact test, etc.), and most importantly, the outcome of the trials (incidence of AF over time/correlation between GERD and AF/multivariate AF prediction model validation). Therefore neither fixed nor random effects’ statistics could be performed. The systematic review structure is far beyond the purpose of the present study. With these data, we could only structure our work as a simple, non-systematic, comprehensive review. The present article is a preliminary step for future systematic reviews and randomized trials.

In conclusion, Data from the literature indicate that GERD may play a role in the initiation and perpetuation of AF. Several mechanisms have been proposed in the attempt to explain this finding, but robust evidence is still lacking. Identifying these mechanisms and their influence on different types of AF could contribute to a better understanding of the pathophysiology of AF in such patients.

In the subset of patients with AF and concomitant GERD, there is weak evidence that PPIs administration could improve AF related symptoms and facilitate conversion to sinus rhythm.

Large randomized clinical studies are required for a more profound understanding of the relationship between GERD and AF.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and atrial fibrillation (AF) are two diseases frequently encountered in clinical practice, with a global impact on the state of health and quality of life for a significant part of the population. Several isolated papers have reported a possible link between these two entities.

Epidemiological data provided by the observational studies analyzed in this article show that the presence of AF in patients with GERD, particular in those with more severe GERD-related symptoms, is higher compared to those without GERD. Treatment with proton pomp inhibitors (PPIs) may improve symptoms related to AF and facilitate conversion to sinus rhythm.

The present article is a comprehensive review of the data published on AF in patients with GERD in adults. Data from the literature indicate that GERD may play a role in the initiation and perpetuation of AF. Several mechanisms have been proposed in the attempt to explain this finding, but robust evidence is still lacking. In the subset of patients with AF and concomitant GERD, there is weak evidence that PPIs administration could improve AF related symptoms.

One of the mechanisms implied in the pathophysiology of AF encountered in patients with GERD is the sympatho-vagal imbalance. The esophageal acid reflux may induce vagal system overstimulation, which acts as a trigger for AF. Treatment with PPIs may improve symptoms related to AF and by facilitating conversion to sinus rhythm with the advantage of being less expensive and with fewer side effects than antiarrhythmic drugs.

GERD and especially esophagitis could initiate and perpetuate paroxysmal AF. Up to the present time, the mechanism of AF as a consequence of gastroesophageal reflux remains unknown, with inflammation and vagal stimulation playing a possible role in the development of these disorders. PPIs therapy could represent an alternative to the standard antiarrhythmic treatment in the subset of patients with AF related to GERD.

This article analyzes the existing data regarding AF in patients with GERD. In the subset of patients with AF and concomitant GERD, there is weak evidence that PPIs administration could improve AF related symptoms and facilitate conversion to sinus rhythm. The present article is a preliminary step for future systematic reviews and randomized trials.

| 1. | Shaheen NJ, Hansen RA, Morgan DR, Gangarosa LM, Ringel Y, Thiny MT, Russo MW, Sandler RS. The burden of gastrointestinal and liver diseases, 2006. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2128-2138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 449] [Cited by in RCA: 479] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Goh KL. Changing epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease in the Asian-Pacific region: an overview. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19 Suppl 3:S22-S25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Vakil N. Disease definition, clinical manifestations, epidemiology and natural history of GERD. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:759-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Friedenberg FK, Xanthopoulos M, Foster GD, Richter JE. The association between gastroesophageal reflux disease and obesity. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2111-2122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Moki F, Kusano M, Mizuide M, Shimoyama Y, Kawamura O, Takagi H, Imai T, Mori M. Association between reflux oesophagitis and features of the metabolic syndrome in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1069-1075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pace F, Bazzoli F, Fiocca R, Di Mario F, Savarino V, Vigneri S, Vakil N. The Italian validation of the Montreal Global definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:394-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-1920; quiz 1943. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Kahrilas PJ, Shaheen NJ, Vaezi MF. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1392-1413, 1413.e1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 438] [Cited by in RCA: 399] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 9. | Lloyd-Jones DM, Wang TJ, Leip EP, Larson MG, Levy D, Vasan RS, D’Agostino RB, Massaro JM, Beiser A, Wolf PA. Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2004;110:1042-1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1411] [Cited by in RCA: 1505] [Article Influence: 68.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Issac TT, Dokainish H, Lakkis NM. Role of inflammation in initiation and perpetuation of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review of the published data. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2021-2028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 415] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Gami AS, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Olson EJ, Nykodym J, Kara T, Somers VK. Obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, and the risk of incident atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:565-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 713] [Cited by in RCA: 789] [Article Influence: 41.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ettinger PO, Wu CF, De La Cruz C, Weisse AB, Ahmed SS, Regan TJ. Arrhythmias and the “Holiday Heart”: alcohol-associated cardiac rhythm disorders. Am Heart J. 1978;95:555-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 431] [Cited by in RCA: 391] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jervell O, Lødøen O. The gastrocardiac syndrome. Acta Med Scand. 1951;142 Suppl:595-599. |

| 14. | Weigl M, Gschwantler M, Gatterer E, Finsterer J, Stöllberger C. Reflux esophagitis in the pathogenesis of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: results of a pilot study. South Med J. 2003;96:1128-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cuomo R, De Giorgi F, Adinolfi L, Sarnelli G, Loffredo F, Efficie E, Verde C, Savarese MF, Usai P, Budillon G. Oesophageal acid exposure and altered neurocardiac function in patients with GERD and idiopathic cardiac dysrhythmias. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:361-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bunch TJ, Packer DL, Jahangir A, Locke GR, Talley NJ, Gersh BJ, Roy RR, Hodge DO, Asirvatham SJ. Long-term risk of atrial fibrillation with symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease and esophagitis. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:1207-1211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kunz JS, Hemann B, Edwin Atwood J, Jackson J, Wu T, Hamm C. Is there a link between gastroesophageal reflux disease and atrial fibrillation? Clin Cardiol. 2009;32:584-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shimazu H, Nakaji G, Fukata M, Odashiro K, Maruyama T, Akashi K. Relationship between atrial fibrillation and gastroesophageal reflux disease: a multicenter questionnaire survey. Cardiology. 2011;119:217-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Huang CC, Chan WL, Luo JC, Chen YC, Chen TJ, Chung CM, Huang PH, Lin SJ, Chen JW, Leu HB. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and atrial fibrillation: a nationwide population-based study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Marcus GM, Smith LM, Scheinman MM, Badhwar N, Lee RJ, Tseng ZH, Lee BK, Kim A, Olgin JE. Proton pump inhibitors are associated with focal arrhythmias. J Innovations Card Rhythm Manage. 2010;1:85-89. |

| 21. | Reddy YM, Singh D, Nagarajan D, Pillarisetti J, Biria M, Boolani H, Emert M, Chikkam V, Ryschon K, Vacek J. Atrial fibrillation ablation in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease or irritable bowel syndrome-the heart to gut connection! J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2013;37:259-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kubota S, Nakaji G, Shimazu H, Odashiro K, Maruyama T, Akashi K. Further assessment of atrial fibrillation as a risk factor for gastroesophageal reflux disease: a multicenter questionnaire survey. Intern Med. 2013;52:2401-2407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Circulation. 1996;93:1043-1065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9482] [Cited by in RCA: 9263] [Article Influence: 308.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tougas G, Kamath M, Watteel G, Fitzpatrick D, Fallen EL, Hunt RH, Upton AR. Modulation of neurocardiac function by oesophageal stimulation in humans. Clin Sci (Lond). 1997;92:167-174. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Tougas G, Spaziani R, Hollerbach S, Djuric V, Pang C, Upton AR, Fallen EL, Kamath MV. Cardiac autonomic function and oesophageal acid sensitivity in patients with non-cardiac chest pain. Gut. 2001;49:706-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hou Y, Scherlag BJ, Lin J, Zhang Y, Lu Z, Truong K, Patterson E, Lazzara R, Jackman WM, Po SS. Ganglionated plexi modulate extrinsic cardiac autonomic nerve input: effects on sinus rate, atrioventricular conduction, refractoriness, and inducibility of atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:61-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 252] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Swanson DR. Running, esophageal acid reflux, and atrial fibrillation: a chain of events linked by evidence from separate medical literatures. Med Hypotheses. 2008;71:178-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Brembilla-Perrot B, Houriez P, Beurrier D, Claudon O, Burger G, Vançon AC, Mock L. Influence of age on the electrophysiological mechanism of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardias. Int J Cardiol. 2001;78:293-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Frustaci A, Chimenti C, Bellocci F, Morgante E, Russo MA, Maseri A. Histological substrate of atrial biopsies in patients with lone atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 1997;96:1180-1184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 912] [Cited by in RCA: 1011] [Article Influence: 34.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Rieder F, Cheng L, Harnett KM, Chak A, Cooper GS, Isenberg G, Ray M, Katz JA, Catanzaro A, O’Shea R. Gastroesophageal reflux disease-associated esophagitis induces endogenous cytokine production leading to motor abnormalities. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:154-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Chung MK, Martin DO, Sprecher D, Wazni O, Kanderian A, Carnes CA, Bauer JA, Tchou PJ, Niebauer MJ, Natale A. C-reactive protein elevation in patients with atrial arrhythmias: inflammatory mechanisms and persistence of atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2001;104:2886-2891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 963] [Cited by in RCA: 1057] [Article Influence: 42.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Liu T, Li L, Korantzopoulos P, Goudevenos JA, Li G. Meta-analysis of association between C-reactive protein and immediate success of electrical cardioversion in persistent atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:1749-1752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Malouf JF, Kanagala R, Al Atawi FO, Rosales AG, Davison DE, Murali NS, Tsang TS, Chandrasekaran K, Ammash NM, Friedman PA. High sensitivity C-reactive protein: a novel predictor for recurrence of atrial fibrillation after successful cardioversion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1284-1287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Korantzopoulos P, Kalantzi K, Siogas K, Goudevenos JA. Long-term prognostic value of baseline C-reactive protein in predicting recurrence of atrial fibrillation after electrical cardioversion. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2008;31:1272-1276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Yamashita T, Sekiguchi A, Iwasaki YK, Date T, Sagara K, Tanabe H, Suma H, Sawada H, Aizawa T. Recruitment of immune cells across atrial endocardium in human atrial fibrillation. Circ J. 2010;74:262-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Osmancik P, Peroutka Z, Budera P, Herman D, Stros P, Straka Z. Changes in cytokine concentrations following successful ablation of atrial fibrillation. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2010;21:278-284. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Maixent JM, Paganelli F, Scaglione J, Lévy S. Antibodies against myosin in sera of patients with idiopathic paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1998;9:612-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Chauhan A, Mullins PA, Taylor G, Petch MC, Schofield PM. Cardioesophageal reflex: a mechanism for “linked angina” in patients with angiographically proven coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:1621-1628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Nishida K, Qi XY, Wakili R, Comtois P, Chartier D, Harada M, Iwasaki YK, Romeo P, Maguy A, Dobrev D. Mechanisms of atrial tachyarrhythmias associated with coronary artery occlusion in a chronic canine model. Circulation. 2011;123:137-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Ellinor PT, Yoerger DM, Ruskin JN, MacRae CA. Familial aggregation in lone atrial fibrillation. Hum Genet. 2005;118:179-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Landmark K, Storstein O. Ectopic atrial tachycardia on swallowing. Report on favourable effect of verapamil. Acta Med Scand. 1979;205:251-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Schilling RJ, Kaye GC. Paroxysmal atrial flutter suppressed by repair of a large paraesophageal hernia. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1998;21:1303-1305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewer: Contini S, Hoff DAL, Kim GH, Pacifico L S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN