CASE REPORT

First case: laparoscopic segmental resection of the ascending colon for a cystic lesion with a fast growth speed

A 36-year-old female patient visited our department with a one-year history of mild intermittent abdominal pain at the right lower quadrant. Five years prior, she had been examined at a local hospital with a complaint of chronic constipation; at the time, colonoscopy revealed a 1.5 cm × 1.0 cm submucosal cystic mass at the ascending colon. The patient received conservative management coupled with endoscopic yearly follow-up, and the cystic lesion had recently become enlarged. There was no significant family history or other medical history. The patient was 170 cm in height and weighed 65 kg (BMI, 22 kg/m2); the ASA grade was 1. She appeared well, and physical examination revealed no remarkable abdominal abnormalities. Laboratory tests, including those measuring tumour markers (CEA, CA125 and AFP), were all within normal limits. Radiographies of the chest and abdomen were normal. Colonoscopy revealed a round, semi-transparent submucosal lesion with a gentle slope and smooth surface at the middle ascending colon (Figure 1A). An abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) scan showed a 4 cm × 4 cm sized, low-density, non-enhancing cystic mass located submucosally at the ascending colon (Figure 2). Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) (EUS2000, Olympus, Japan) revealed a 3.9 cm × 3.5 cm lesion visible as an echo-free cyst in the third (submucosal) layer without blood flow. The lesion had a positive cushion (pillow) sign (Figure 3A). The patient underwent laparoscopic segmental resection of the ascending colon.

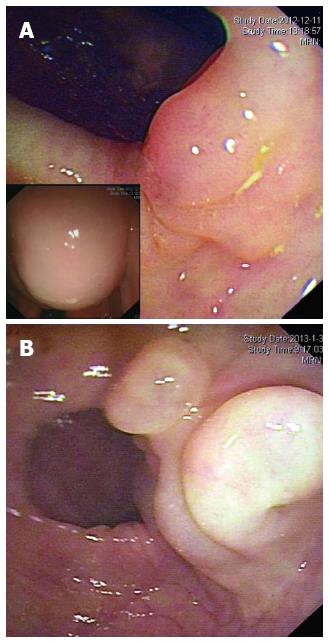

Figure 1 Endoscopic findings for the two cases.

A round, semi-transparent and wide-based submucosal lesion at the ascending colon in Case 1 (A) and a sharply marginated, lobular submucosal lesion at the sigmoid colon in Case 2 (B) with gentle slopes and smooth surfaces are noted. Left bottom of Figure 1A shows that when the patient's position was altered, the shape of the mass changed and was fluctuant on palpation.

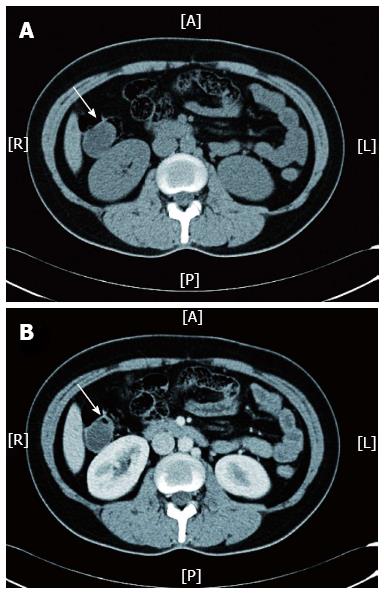

Figure 2 Abdominopelvic computed tomography scan for Case 1 revealed a cystic mass (indicated by white arrow) located at the ascending colon, which was visible in a non-contrast scan (A) and was not enhanced after the arterial phase (B).

A: Anterior; R: Right; L: Left; P: Posterior.

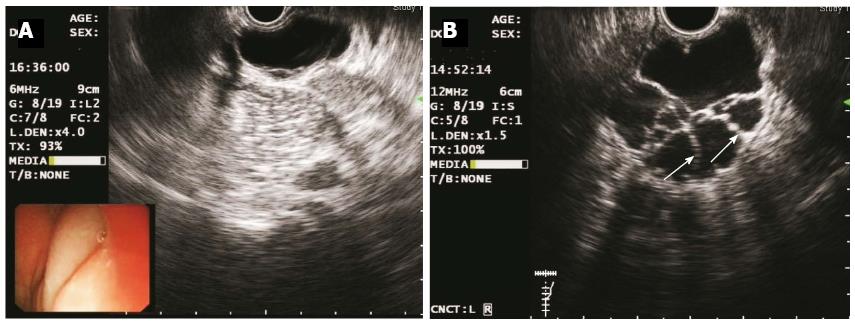

Figure 3 Endoscopic ultrasonography images of the two cases obtained using a catheter EUS probe.

A: Elevated lesions as echo-free, homogenous cysts in Case 1 (frequency 6 MHz); B: Multiple septal walls (indicated by white arrows) in Case 2 (frequency 12 MHz); EUS revealed that both lesions were located in the third (submucosal) layer.

In brief, five ports were made, with two 12 mm and three 5 mm cannulas placed as previously described[6]. The ascending mesocolon was mobilised using a lateral-to-medial approach. The ileocolic pedicle was resected, and the right flexure taken down. The ascending colon was freed and the specimen was extracted through an incision extended from the supraumbilical port site. A segment of involved colon approximately 6-7 cm in length was resected and an side-to-side anastomosis was accomplished extracorporeally using a linear-cutter (Proximate®, Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH, United States). The patient had an uneventful recovery and was discharged seven days post-operation. Pathological analysis identified the mass as a submucosal macrocystic lymphangioma (Figure 4A). Annual endoscopic follow-up for 3 years was recommended for the patient.

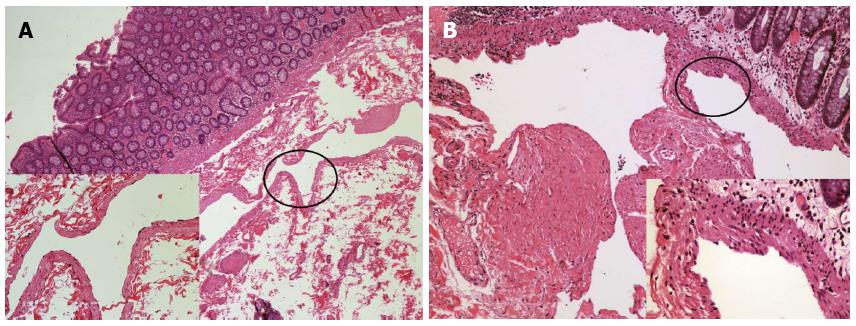

Figure 4 Histopathological examination of the two cases after hematoxylin and eosin stain (at × 40 magnification for low power field images).

A: Case 1 revealed a dilated submucosal cyst lined with a single layer of endothelial cells [left bottom, hematoxylin and eosin (HE) stain, × 200]; B: Case 2 displayed lymphatic vessels of varied sizes, which were covered by a flattened layer of lymphatic epithelium. The smooth muscle layer of the vessels is also noted (right bottom, HE stain, × 400).

Second case: laparoscopic segmental sigmoidectomy for the cystic mass with concurrent polyps

A 50-year-old male patient with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus was admitted for an incidental finding of a lobulated cystic mass at the sigmoid colon. The patient had a history of colorectal polyps and had undergone endoscopic polypectomy 2 years prior. He was asymptomatic and appeared well with a BMI of 22 kg/m2 and ASA grade 2. Blood chemistry and normal tumour maker (CEA, AFP, CA50 and CA125) tests were normal. Abdominal CT did not show significant abnormality due to bowel flatulence. Colonoscopy revealed that in addition to four sessile polyps ranging from 0.3 to 0.5 cm in diameter, the patient had an extra 3.0 cm × 3.5 cm lobular submucosal lesion located 20-25 cm above the anal verge. The lesion colour did not differ from that of the surrounding normal mucosa, and there were no ulcerations or erosions on the smooth surface (Figure 1B). Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS2000, Olympus, Japan) revealed multiple internal submucosal septa (Figure 3B). In order to remove the section affected by the cystic lesion and polyps, the patient underwent laparoscopic segmental sigmoidectomy. In brief, five ports were made with two 12 mm and three 5 mm cannulas placed as previously described[7]. The inferior mesenteric artery was identified and resected. The descending and sigmoid mesocolon was mobilised, and the specimen was extracted through an incision extending from the suprapubic port. A segment of sigmoid colon, approximately 8 cm in length, was resected extracorporeally. The distal colon was reintroduced into the abdominal cavity after the anvil of the circular stapler was introduced and fixed inside. Pneumoperitoneum was reestablished and a double-stapled anastomosis between the distal colon and the proximal rectal stump was accomplished intra-abdominally. An uncomplicated postoperative recovery was achieved, and the patient was discharged at the sixth day post-operation. The pathologic features were diagnostic of macrocystic lymphangioma (Figure 4B). Annual endoscopic follow-up for at least 3 years was recommended.

DISCUSSION

Lymphangioma may be developmentally malformed or malpositioned lymphatic tissue, and, though its exact aetiology remains unclear, genetic abnormalities might also play a role[8]. We herein discuss the pathology, diagnostic modality and treatment options for this unusual lymphatic malformation of the colon based on the cases described above.

Macroscopically, colonic lymphangiomas can be classified as one of the following three types: simple (capillary), cavernous and cystic. The cystic type is the most frequently reported[5]. Cystic lymphangiomas are yellow, greyish, or yellow-pink in colour, and they often appear as multiple cysts or spongy masses with cavities containing watery or milky fluids[9]. Cystic lymphangiomas may be classified into microcystic, macrocystic, and mixed subtypes according to the cyst volume (2 cm3 is used as the cutoff value)[10]. Both of our cases were classified as colonic macrocystic lymphangioma. Microscopically, as shown in Figure 4, the macrocystic mass is characterised by thin-walled spaces, which are frequently surrounded by lymph and/or lymphocytes, and is lined by flattened endothelium. The mass is also situated in close proximity to collagenous elastic tissue and smooth muscle[11].

Colonic lymphangiomas usually present as submucosal polypoid lesions without any symptomatic presentation. Some patients may experience episodic constipation with vague abdominal distress, diarrhea or other nonspecific symptoms[9,12]. Haemorrhage or anaemia[13,14] and protein-losing enteropathy[5,15] are always associated with surface ulceration or erosion. Acute abdomen obstruction of the volvulus, intussusceptions and bowel may occur when a mass is sufficiently enlarged[16-18]. Abdominal pain may mimic acute appendicitis[12,19].

Most colonic lymphangiomas are preoperatively diagnosed as submucosal tumours using colonoscopy, which is the most commonly used diagnostic modality. Lymphangioma appears as a well-defined, submucosal cystic lesion, typically with a smooth, pinkish, translucent surface[20]. Endoscopic ultrasonography is useful for diagnosing colonic lymphangioma. When using EUS, the characteristic features of colonic lymphangioma are lesions localised at the submucosal layer with a homogenous echo pattern and multilocular cysts that are echo-free or contain septal structures[21]. Endoscopic aspiration for cytology evaluation or biopsy often has no diagnostic value and may result in an efflux of lymphatic fluid[20] or even local infection[22]. Abdominal CT may detect non-enhancing submucosal cystic masses and can be recommended to rule out coexisting intraperitoneal co-morbid lesions[5]. Both of the cases described here underwent these routine diagnostic modalities, which revealed the characteristic features mentioned above.

Management of colonic lymphangiomas is dependent on their size, growth speed, symptoms and degree of suspected malignancy[17]. Malignant transformation of colonic lymphangiomas does not occur[11]. Therefore, close endoscopic surveillance can be considered and spontaneous resolution may occur[13,23]. With respect to sclerotherapy for lymphangiomas, agents such as Bleomycin, sodium tetradecyl sulphate, or OK-432 (lyophilised incubation mixture of group A streptococcus pyogenes of human origin) are routinely used. Macrocystic lesions, but not microcystic lesions, respond well to OK-432 injections[24]. Most of the reported cases of lymphangioma have occurred in the head and neck of children[1,25-27]. To the best of our knowledge, the use of endoscopic sclerotherapy to treat colonic lesions has not previously been reported. The complications resulting from the use of this therapy, which include local infection, perforation and bleeding, should be considered[28]. Other non-surgical therapy, including steroids, fibrin glue, or Ethibloc, has not been established as superior to surgery[29,30].

Colonic lymphangioma can be complicated by concurrent colon cancer or adenoma[12]. The mass might form secondarily as a result of lymphatic obstruction and inflammatory processes due to various causes[13,30-32]. Additionally, the potential to grow and invade adjacent structures introduce risks of life-threatening complications[17], and, as a result, surgical interventions may be required. In the current cases, they were implicated to surgical intervention for the reason of relatively large and fast growing lesion or lesion with concurrent polyps.

Endoscopic resection has been recommended for intraluminal tumours with a maximum diameter 2.5 cm or smaller[12,21]. Matsuda et al[12] reviewed 279 Japanese cases of colorectal lymphangiomas. Of them, 104 (37.4%) patients underwent endoscopic resection. Removing the entire lesion as completely as possible, rather than using mere puncture and drainage, was the most important factor for reducing the risk of recurrence[20,33-35].

In 1996, Kenney et al[36] reported the first case of laparoscopic excision of a cystic lymphangioma from the mesentery of the proximal jejunum. Ryu et al[37] reported two cases of huge mesenteric cystic lymphangioma (13 and 11 cm in diameter), both of which were treated laparoscopically, with partial aspiration of the cysts using a spinal needle. Hoffmann et al[38] reported a 4.5 cm cystic lesion in the cecal region. The cyst, including its base and a portion of the colon, was resected laparoscopically. However, these cases were all lymphangiomas originating from the mesentery, which is the most commonly involved intra-abdominal site[20].

In both of our cases, it was difficult to find the masses laparoscopically because they were located at the submucosal layer. Additionally, both masses were relatively large and could not be removed either laparoscopically or endoscopically while preserving the involved colon. It is critical to preoperatively identify and locate masses using endoscopic staining[39]. According to our experience, neither technique makes it challenging nor time consuming to remove the specimen and facilitate anastomosis with a small incision (approximately 4 cm in length). Compared to traditional open approaches, laparoscopic surgery has various advantages, including less intraoperative blood loss, decreased postoperative pain, a shorter hospital stay, minimal scarring, and a faster return to normal activities[40].

COMMENTS

Case characteristics

A 36-year-old female (Case 1) and another 40-year-old male (Case 2) presented with mild intermittent abdominal pain and without specific symptoms, respectively; initially, cystic lesions at the colon were accidentally found using colonoscopy.

Clinical diagnosis

An enlarged submucosal cystic mass at the middle ascending colon for Case 1 and a lobular submucosal lesion coupled with four polyps located at the sigmoid colon for Case 2.

Differential diagnosis

Other submucosal tumours, such as leiomyoma, lipoma or other cystic lesions, such as enteric duplication cysts and colitis cystica profunda as well as carcinoid tumours or mucocele, should be considered as the differential diagnoses.

Laboratory diagnosis

In both cases, the blood chemistry and tumour marker level tests were all within normal limits.

Imaging diagnosis

In Case 1, colonoscopy revealed a round semi-transparent submucosal lesion (4 cm × 4 cm), abdominal CT revealed a non-enhancing submucosal cystic mass and EUS revealed an echo-free cyst in the third layer without blood flow. In Case 2, colonoscopy revealed a lobular submucosal lesion (3.0 cm × 3.5 cm) coupled with four polyps (0.3-0.5 cm in diameter) at 20-25 cm above the anal verge; EUS revealed multiple submucosal internal septa.

Pathological diagnosis

Pathological analysis revealed the colonic masses in both cases to be macrocystic lymphangiomas.

Treatment

Laparoscopic segmental ascending colectomy and sigmoidectomy were performed on Case 1 and Case 2, respectively.

Related reports

Both cases had uneventful postoperative recoveries.

Term explanation

A laparoscopic segmental colectomy is a minimally invasive procedure that involves removing a portion or segment of the colon.

Experiences and lessons

This report not only represents two unusual cases of colonic cystic lymphangiomas, it also suggests that surgical intervention is required in some situations and that the laparoscopic approach is an attractive option for this rare benign malformation.

Peer review

This article describes a minimally invasive surgical alternative for managing an unusual condition compared to an endoscopic approach or open surgery. This definitive surgical resection offers more success than endoscopic excision in terms of the relapse rate.