Published online Jul 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8617

Revised: March 10, 2014

Accepted: April 21, 2014

Published online: July 14, 2014

Processing time: 184 Days and 2.4 Hours

AIM: To investigate the need for pancreatic stenting after endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) in patients with difficult biliary cannulation.

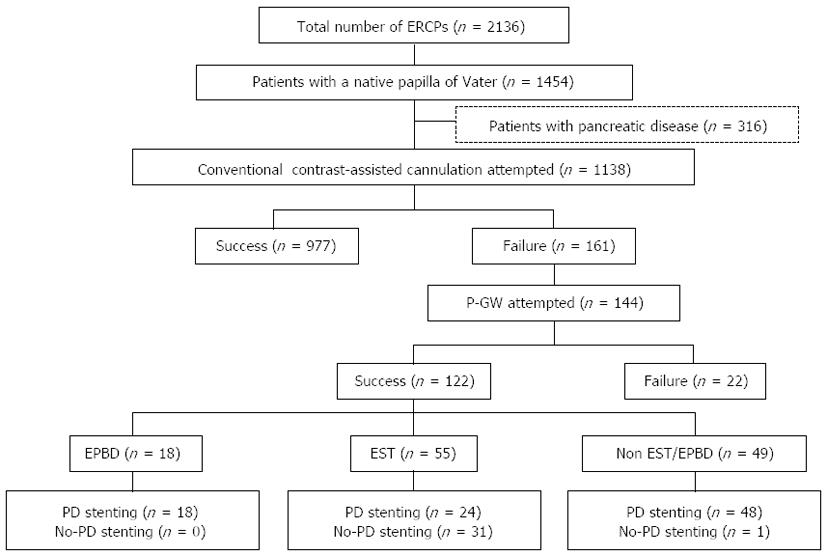

METHODS: Between April 2008 and August 2013, 2136 patients underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)-related procedures. Among them, 55 patients with difficult biliary cannulation who underwent EST after bile duct cannulation using the pancreatic duct guidewire placement method (P-GW) were divided into two groups: a stent group (n = 24; pancreatic stent placed) and a no-stent group (n = 31; no pancreatic stenting). We retrospectively compared the two groups to examine the need for pancreatic stenting to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) in patients undergoing EST after biliary cannulation by P-GW.

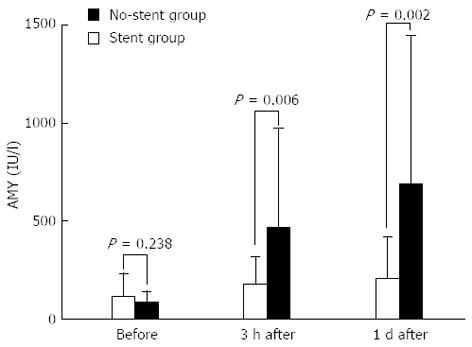

RESULTS: No differences in patient characteristics or endoscopic procedures were observed between the two groups. The incidence of PEP was 4.2% (1/24) and 29.0% (9/31) in the Stent and no-stent groups, respectively, with the no-stent group having a significantly higher incidence (P = 0.031). The PEP severity was mild for all the patients in the stent group. In contrast, 8 had mild PEP and 1 had moderate PEP in the no-stent group. The mean serum amylase levels (means ± SD) 3 h after ERCP (183.1 ± 136.7 vs 463.6 ± 510.4 IU/L, P = 0.006) and on the day after ERCP (209.5 ± 208.7 vs 684.4 ± 759.3 IU/L, P = 0.002) were significantly higher in the no-stent group. A multivariate analysis identified the absence of pancreatic stenting (P = 0.045; odds ratio, 9.7; 95%CI: 1.1-90) as a significant risk factor for PEP.

CONCLUSION: In patients with difficult cannulation in whom the bile duct is cannulated using P-GW, a pancreatic stent should be placed even if EST has been performed.

Core tip: We retrospectively examined the need for pancreatic stenting after endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) in patients with difficult biliary cannulation in whom the bile duct was cannulated using the pancreatic duct guidewire placement method (P-GW). The incidences of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis (PEP) were 4.2% and 29.0% in the Stent and no-stent groups, respectively, with the no-stent group having a significantly higher incidence (P = 0.031). A multivariate analysis identified the absence of pancreatic stenting as a significant risk factor for PEP. Therefore, in patients with difficult cannulation in whom the bile duct is cannulated using P-GW, a pancreatic stent should be placed even if EST has been performed.

- Citation: Nakahara K, Okuse C, Suetani K, Michikawa Y, Kobayashi S, Otsubo T, Itoh F. Need for pancreatic stenting after sphincterotomy in patients with difficult cannulation. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(26): 8617-8623

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i26/8617.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8617

While various causes of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis (PEP) have been noted, the most common cause is obstruction to the outflow of pancreatic juice due to edema of the papilla of Vater[1,2]. In recent years, many randomized controlled trials have shown the usefulness of pancreatic stenting for preventing the development of PEP[1-5].

Endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) is also considered an effective procedure for preventing PEP because it enables the outflow of pancreatic juice[6-8]. Thus, it is still unclear whether there is an additional need for pancreatic stenting to prevent PEP in patients who undergo EST. Because the pancreatic duct orifice remains patent after EST, the placement of a pancreatic spontaneous dislodgement stent without flaps for the prevention of PEP often results in the premature dislodgement of the stent.

Thus, in this study, we examined the additional need for pancreatic stenting to prevent PEP in patients undergoing EST. Patients with difficult biliary cannulation who underwent EST after selective biliary cannulation by the pancreatic duct guidewire placement method (P-GW)[9-11] were divided into two groups according to whether pancreatic stenting had occurred, and we compared the treatment outcomes and incidence of complications between the two groups. A multivariate analysis was performed to identify risk factors for the development of PEP in patients undergoing EST after biliary cannulation by P-GW.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)-related procedures were performed in 2136 cases at the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology of the St. Marianna University School of Medicine Hospital between April 2008 and August 2013. In our department, biliary cannulation is first attempted using the conventional contrast-assisted cannulation (CC) method. However, in cases where bile duct cannulation is difficult to perform using CC but in which a guidewire can be placed in the pancreatic duct, P-GW is employed as the procedure of first choice to achieve biliary cannulation. A second cannula was passed into the same working channel of the scope alongside the guidewire using the two-devices-in-one-channel method[12], and biliary cannulation was attempted.

Of the 2136 patients who underwent ERCP-related procedures during the study period, 1454 had a native papilla. After 316 patients who did not undergo biliary cannulation or who had pancreatic diseases were excluded, 1138 patients remained. Biliary cannulation was achieved using CC in 977 of these patients. Then, among the 161 patients who experienced difficult biliary cannulation using CC, P-GW was attempted in 144, and successful biliary cannulation was achieved in 122 patients. Among these 122 patients with successful biliary cannulation using P-GW, EST was performed in 55, endoscopic papillary balloon dilation (EPBD) was performed in 18, and no papillary procedure was performed in 49 patients. EST was performed using an electrosurgical generator in the 120-Watt Endocut mode (ICC 200: ERBE Corp., Tuebingen, Germany). Following EST, a pancreatic duct stent was placed in 24 patients (stent group), whereas no pancreatic stenting was performed in the remaining 31 cases (no-stent group) (Figure 1). The pancreatic duct stents used were all 5-Fr, 3-cm-long spontaneous dislodgement stents with a single duodenal pigtail (Pit-stent, Gadelius Medical, Tokyo, Japan).

Decisions regarding whether pancreatic stenting was necessary were left to the discretion of the endoscopist performing each procedure. All the procedures were supervised by a single expert, who performs approximately 500-600 ERCPs per year. Because our hospital is an educational institution, trainees performed approximately half of the procedures. However, when deep cannulation of the bile duct was not achieved within 15 min, the expert took over the procedure. In all cases, 600 mg of gabexate mesilate was administered on the day of the procedure to prevent PEP. The patients’ serum amylase levels (normal range: 37-124 IU/L) were measured prior to, 3 h after, and 1 d after the ERCP procedure.

The stent group (n = 24), in which pancreatic stenting was performed after EST, and the no-stent group (n = 31), in which no pancreatic duct stent was placed after EST, were retrospectively compared in terms of patient characteristics (age, sex, primary disease, history of pancreatitis, and peripapillary diverticulum), endoscopic procedures (diameter of the pancreatic duct guidewire, range of EST incision, biliary maneuver, and procedure time), incidence of PEP, complication rate, and serum amylase levels. Moreover, univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify the risk factors for PEP in patients undergoing EST after biliary cannulation by P-GW.

The ranges of the EST incisions were defined as follows: an incision up to the hooding fold was considered a small incision, an incision up to the upper border of the oral protrusion was a large incision, and an incision with a range between those of small and large incisions was an intermediate incision. The diagnosis of pancreatitis and the determination of its severity were based on consensus guidelines proposed by Cotton et al[13]. Moreover, complications, such as bleeding, perforation, and cholangitis, were also diagnosed according to the consensus guidelines proposed by Cotton et al[13].

The statistical analysis was performed using Fisher’s exact test or Welch’s t-test, as appropriate. To identify risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis, variables found to be possibly significant (P < 0.2) by univariate analysis were entered into a multiple logistic regression model. P values < 0.05 were regarded as denoting significance. The statistical analysis was performed using the Prism 5 program (GraphPad Software, Inc., CA, United States) and SPSS (version 19; SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States).

No significant differences in age, sex, distribution of primary diseases, history of pancreatitis, or presence/absence of peripapillary diverticulum were observed between the Stent and no-stent groups (Table 1). Moreover, the analysis of endoscopic procedure-related variables revealed no significant differences in the diameter of the pancreatic duct guidewire, range of EST incision, biliary maneuver, or procedure time between the Stent and no-stent groups (Table 2).

| Stent group (n = 24) | No-stent group (n = 31) | P-value | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 70.8 ± 12.8 | 72.4 ± 10.0 | 0.631 |

| Sex (male/female) | 11/13 | 16/15 | 0.788 |

| History of pancreatitis | 0 | 0 | |

| Periampullary diverticulum | 10 | 13 | 1.000 |

| Choledocholithiasis | 15 | 21 | 0.778 |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 4 | 7 | 0.739 |

| Acute cholecystitis | 3 | 3 | 1.000 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 2 | 0 | 0.186 |

| Gallbladder carcinoma | 1 | 1 | 1.000 |

| Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction | 1 | 1 | 1.000 |

| Liver metastasis | 0 | 1 | 1.000 |

| Stent group (n = 24) | No-stent group (n = 31) | P-value | |

| Pancreatic guidewire diameter (0.025 inch or 0.035 inch) | 12/12 | 16/15 | 1.000 |

| Incision range of EST | |||

| Small | 3 | 4 | 1.000 |

| Medium | 21 | 26 | 1.000 |

| Large | 0 | 1 | 1.000 |

| Endoscopic biliary stenting | 14 | 11 | 0.109 |

| Bile duct stone removal | 10 | 19 | 0.180 |

| Intraductal ultrasonography | 7 | 10 | 1.000 |

| Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage | 3 | 6 | 0.716 |

| Biopsy of the bile duct | 2 | 7 | 0.271 |

| Cytology of the bile juice | 3 | 6 | 0.716 |

| Endoscopic naso-gallbladder drainage | 3 | 2 | 0.643 |

| Peroral cholangioscopy | 0 | 3 | 0.249 |

| Procedure time (min, mean ± SD) | 59.3 ± 19.0 | 66.4 ± 21.6 | 0.207 |

The incidence of PEP was 4.2% (1/24) in the stent group and 29.0% (9/31) in the no-stent group, with the no-stent group having a significantly higher incidence (P = 0.031) (Table 3). The PEP severity was mild for all the patients in the stent group. In contrast, among the 9 PEP patients in the no-stent group, 8 had mild PEP and 1 had moderate PEP. Intermediate EST incisions were performed in all the patients in the stent group with PEP, whereas among the 9 patients in the no-stent group with PEP, 3 received small incisions, 5 received intermediate incisions, and 1 received a large incision. Conservative therapy without additional endoscopic procedures resulted in improvement in all the patients.

| Stent group (n = 24) | No-stent group (n = 31) | P-value | |

| Overall complications | 3 (12.5) | 11 (35.5) | 0.067 |

| Pancreatitis | 1 (4.2) | 9 (29.0) | 0.031 |

| Bleeding | 2 (8.3) | 2 (6.5) | 1.000 |

| Perforation | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Cholangitis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

With regard to complications other than PEP, bleeding was observed in 2 patients each in the stent group (2/24; 8.3%) and the no-stent group (2/31; 6.5%), with no significant difference in incidence between the two groups (P = 1.000). No other complications, such as perforation or cholangitis, were observed in either group. The overall complication rate, including PEP, was 12.5% (3/24) in the stent group and 35.5% (11/31) in the no-stent group. Although the difference was not significant, the rate tended to be higher in the no-stent group (P = 0.067) (Table 3).

The serum amylase levels (means ± SD) in the stent group were 118 ± 116.9 IU/L before ERCP, 183.1 ± 136.7 IU/L 3 h after ERCP, and 209.5 ± 208.7 IU/L one day after ERCP; the corresponding values in the no-stent group were 85.5 ± 56.0, 463.6 ± 510.4 and 684.4 ± 759.3 IU/L, respectively. Although no significant difference in the serum amylase levels before ERCP was observed between the Stent and no-stent groups (P = 0.238), the levels 3 h after and one day after ERCP were significantly higher in the no-stent group (P = 0.006 and P = 0.002, respectively) (Figure 2).

The univariate analysis identified the absence of pancreatic duct stenting (P = 0.031; OR, 9.4; 95%CI: 1.1-81) and the incidence of endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (P = 0.047; OR, 5.3; 95%CI: 1.1-26) as significant risk factors for PEP (Table 4). The multivariate analysis identified the absence of pancreatic stenting (P = 0.045; OR, 9.7; 95%CI: 1.1-90) as the only significant risk factor (Table 5).

| Univariate analysis | Pancreatitis (+) (n = 10) | Pancreatitis (-) (n = 45) | P-value | OR (95%CI) |

| Age (< 60 yr) | 2 | 9 | 1.000 | 1.0 (0.18-5.5) |

| Female gender | 5 | 23 | 1.000 | 0.96 (0.24-3.8) |

| Periampullary diverticulum | 3 | 20 | 0.494 | 0.54 (0.12-2.3) |

| Pancreatic guidewire (0.035 inch) | 4 | 23 | 0.729 | 0.64 (0.16-2.6) |

| EST incision range (small) | 3 | 4 | 0.104 | 4.4 (0.80-24) |

| No pancreatic duct stenting | 9 | 22 | 0.031 | 9.4 (1.1-81) |

| Endoscopic biliary stenting | 3 | 22 | 0.318 | 0.45 (0.10-2.0) |

| Bile duct stone removal | 5 | 24 | 1.000 | 0.88 (0.22-3.5) |

| Intraductal ultrasonography | 4 | 13 | 0.479 | 1.6 (0.40-6.8) |

| Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage | 4 | 5 | 0.047 | 5.3 (1.1-26) |

| Biopsy of the bile duct | 3 | 6 | 0.340 | 2.8 (0.56-14) |

| Cytology of the bile juice | 3 | 6 | 0.340 | 2.8 (0.56-14) |

| Endoscopic naso-gallbladder drainage | 1 | 4 | 0.220 | 3.5 (0.50-24) |

| Peroral cholangioscopy | 1 | 2 | 0.459 | 2.4 (0.20-29) |

| Procedure time (> 60 min) | 5 | 19 | 0.733 | 1.4 (0.35-5.4) |

| Multivariate analysis | P-value | OR (95%CI) |

| Incision range of EST ( ≤ small) | 0.150 | 4.7 (0.57-40) |

| No pancreatic duct stenting | 0.045 | 9.7 (1.1-90) |

| Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage | 0.101 | 4.6 (0.74-29) |

The precut[14] and P-GW techniques[9-11,15,16] have been employed for patients with difficult biliary cannulation. The precut technique is difficult to perform and is reported to be associated with a high incidence of complications, such as bleeding, perforation, and pancreatitis[17]. Therefore, we perform P-GW as a first choice for patients in whom a guidewire can be placed in the pancreatic duct. Previous studies of the efficacy of P-GW have reported varied results, with the success rate of biliary cannulation ranging from 43.8% to 92.6%[9-11,15,16]. However, the studies reporting low success rates (in the 40% range) for biliary cannulation also included patients for whom the placement of a guidewire in the pancreatic duct was unsuccessful; such patients are not considered suitable candidates for P-GW[15,16]. When such cases are excluded, the success rate of biliary cannulation using P-GW is high, ranging from 72.6% to 92.6%[10,11].

Another advantage of P-GW, if the procedure can be completed with the guidewire placed in the pancreatic duct, is the ease of placing a pancreatic stent at the end of the procedure. Difficult biliary cannulation is considered a procedure-related risk factor for PEP[18]. It is critical to conduct additional research into the prevention of PEP in patients with difficult biliary cannulation who require P-GW.

In recent years, a number of randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the usefulness of pancreatic stenting for the prevention of PEP[1-5]. Ito et al[4] reported the usefulness of pancreatic stenting for preventing PEP in patients with difficult biliary cannulation for whom bile duct cannulation was achieved using P-GW. According to their results, the success rate of pancreatic stenting after biliary cannulation with P-GW was 92.9% (26/28 patients), and the 22.9% incidence of PEP in the group without pancreatic stent placement was significantly higher than the 2.9% incidence in the group that underwent pancreatic stent placement (relative risk, 0.13; 95%CI: 0.016-0.95). Thus, in addition to improving the success rate of biliary cannulation in patients with difficult biliary cannulation, the use of P-GW results in a higher success rate of pancreatic stenting and facilitates the prevention of PEP.

EST is also considered effective for the prevention of PEP because EST reduces the obstruction of the pancreatic juice outflow[6-8]. However, it remained unclear whether additional pancreatic stenting might also be necessary for preventing PEP in patients undergoing EST. Because the pancreatic duct remains patent after EST, the placement of a pancreatic spontaneous dislodgement stent without flaps to prevent PEP often results in the premature dislodgement of the stent. There have also been concerns that the stents may not be sufficiently effective.

However, in our study, the incidence of PEP in the no-stent group was 29.0%, which was significantly higher than the 4.2% incidence in the stent group. The serum amylase levels after ERCP were also significantly higher in the no-stent group compared with the stent group. The multivariate analysis identified the absence of pancreatic duct stenting as the only significant risk factor for PEP. Thus, these findings support that in patients with difficult biliary cannulation for whom P-GW is used to achieve bile duct cannulation, a pancreatic duct stent should be placed to prevent PEP even if EST has been performed.

The need for pancreatic stenting after EST is presumed to be due to the insufficient opening of the pancreatic duct orifice by EST and the potential obstruction of the free outflow of pancreatic juice by the thermocoagulation degeneration of the pancreatic duct orifice. Furthermore, because pancreatography was performed in all of the patients in this study, the increased internal pressure of the pancreatic duct compared with the opening of the pancreatic duct orifice might have influenced the results. Additionally, this study included patients with difficult cannulation in whom edema of the papilla of Vater may have spread extensively.

Theoretically, creating a large EST incision by applying electric discharges for a brief period of time will open the pancreatic duct without causing electrosurgical current-induced edema, thereby preventing PEP. However, according to the results of this study, PEP occurred in only one patient in the no-stent group, who received a large incision. Moreover, neither the univariate nor the multivariate analysis identified a small EST incision as a risk factor for PEP. Thus, the association between the range of the incision and the incidence of PEP remains unclear. However, because PEP occurred in 3 of the 4 patients in the no-stent group who received a small EST incision, a small incision cannot be excluded as a risk factor for PEP. Further studies with larger sample sizes would be needed to clarify this issue.

In conclusion, in patients with difficult biliary cannulation who undergo successful biliary cannulation using P-GW, it appears that a pancreatic duct stent should be placed to prevent PEP even if EST is performed. However, because of the limitations of our study, including the small sample size and the retrospective design, further prospective studies using larger sample sizes will be needed to confirm our findings.

The pancreatic duct guidewire placement method is reported to be effective in patients with difficult biliary cannulation. However, difficult biliary cannulation is associated with a high incidence of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis (PEP).

The efficacy of pancreatic stenting to prevent PEP in patients with difficult cannulation has been reported. However, endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) is also considered effective for preventing PEP because it facilitates the outflow of pancreatic juice.

The authors examined the incidence of PEP in patients with difficult cannulation for whom the bile duct was cannulated using P-GW with or without pancreatic stenting. The incidence of PEP was 4.2% and 29.0% in the stent and no-stent groups, respectively, with the incidence in the no-stent group being significantly higher. A multivariate analysis identified the absence of pancreatic stenting as a significant risk factor for PEP.

In patients with difficult cannulation for whom the bile duct is cannulated using P-GW, a pancreatic stent should be placed even if EST has been performed.

The authors report the incidence of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)-pancreatitis in patients with difficult ERCP undergoing the pancreatic duct guidewire placement method of biliary cannulation with or without a PD stent. This is an interesting study.

| 1. | Tarnasky PR, Palesch YY, Cunningham JT, Mauldin PD, Cotton PB, Hawes RH. Pancreatic stenting prevents pancreatitis after biliary sphincterotomy in patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1518-1524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fazel A, Quadri A, Catalano MF, Meyerson SM, Geenen JE. Does a pancreatic duct stent prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis? A prospective randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:291-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sofuni A, Maguchi H, Itoi T, Katanuma A, Hisai H, Niido T, Toyota M, Fujii T, Harada Y, Takada T. Prophylaxis of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis by an endoscopic pancreatic spontaneous dislodgement stent. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1339-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Obana T, Horaguchi J, Takasawa O, Koshita S, Kanno Y, Ogawa T. Can pancreatic duct stenting prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis in patients who undergo pancreatic duct guidewire placement for achieving selective biliary cannulation? A prospective randomized controlled trial. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1183-1191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kawaguchi Y, Ogawa M, Omata F, Ito H, Shimosegawa T, Mine T. Randomized controlled trial of pancreatic stenting to prevent pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1635-1641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Simmons DT, Petersen BT, Gostout CJ, Levy MJ, Topazian MD, Baron TH. Risk of pancreatitis following endoscopically placed large-bore plastic biliary stents with and without biliary sphincterotomy for management of postoperative bile leaks. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1459-1463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nakai Y, Isayama H, Togawa O, Kogure H, Tsujino T, Yagioka H, Yashima Y, Sasaki T, Ito Y, Matsubara S. New method of covered wallstents for distal malignant biliary obstruction to reduce early stent-related complications based on characteristics. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:49-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jeong YW, Shin KD, Kim SH, Kim IH, Kim SW, Lee KA, Jeon BJ, Lee SO. [The safety assessment of percutaneous transhepatic transpapillary stent insertion in malignant obstructive jaundice: regarding the risk of pancreatitis and the effect of preliminary endoscopic sphincterotomy]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009;54:390-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dumonceau JM, Devière J, Cremer M. A new method of achieving deep cannulation of the common bile duct during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Endoscopy. 1998;30:S80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Maeda S, Hayashi H, Hosokawa O, Dohden K, Hattori M, Morita M, Kidani E, Ibe N, Tatsumi S. Prospective randomized pilot trial of selective biliary cannulation using pancreatic guide-wire placement. Endoscopy. 2003;35:721-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Obana T, Horaguchi J, Takasawa O, Koshita S, Kanno Y. Pancreatic guidewire placement for achieving selective biliary cannulation during endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5595-600; discussion 5599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Kimura K, Yago A. ERCP for intradiverticular papilla: two-devices-in-one-channel method. Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:517-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1890] [Cited by in RCA: 2087] [Article Influence: 59.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Huibregtse K, Katon RM, Tytgat GN. Precut papillotomy via fine-needle knife papillotome: a safe and effective technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 1986;32:403-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Xinopoulos D, Bassioukas SP, Kypreos D, Korkolis D, Scorilas A, Mavridis K, Dimitroulopoulos D, Paraskevas E. Pancreatic duct guidewire placement for biliary cannulation in a single-session therapeutic ERCP. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1989-1995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Herreros de Tejada A, Calleja JL, Díaz G, Pertejo V, Espinel J, Cacho G, Jiménez J, Millán I, García F, Abreu L. Double-guidewire technique for difficult bile duct cannulation: a multicenter randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:700-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1704] [Article Influence: 56.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 18. | Freeman ML, DiSario JA, Nelson DB, Fennerty MB, Lee JG, Bjorkman DJ, Overby CS, Aas J, Ryan ME, Bochna GS. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:425-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 801] [Cited by in RCA: 853] [Article Influence: 34.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewers: Shehata MMM, Sofi A S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN