Published online Jun 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i21.6675

Revised: December 11, 2013

Accepted: February 20, 2014

Published online: June 7, 2014

Processing time: 202 Days and 14.1 Hours

Deep infiltrating endometriosis is an often-painful disorder affecting women during their reproductive years that usually involves the structures of the pelvis and frequently the gastrointestinal tract. We present the case of a 37-year-old female patient with an endometrial growth on the sigmoid colon wall causing pain, diarrhea and the presence of blood in the feces. The histology of the removed specimen also revealed the involvement of the utero-vesical fold, the recto-vaginal septum and a pericolic lymph node, which are all quite uncommon findings. To identify the endometrial cells, we performed immunohistochemical staining for CD10 and the estrogen and progesterone receptors.

Core tip: We present the case of a 37-year-old female patient with an endometrial growth on the sigmoid colon wall causing pain, diarrhea and the presence of blood in the feces associated with the involvement of the utero-vesical fold, the recto-vaginal septum and a pericolic lymph node, which are quite uncommon findings. We also reviewed the literature to examine the behavior of deep infiltrating endometriosis, analyzing the risk of recurrence related to the possible treatments.

- Citation: Cacciato Insilla A, Granai M, Gallippi G, Giusti P, Giusti S, Guadagni S, Morelli L, Campani D. Deep endometriosis with pericolic lymph node involvement: A case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(21): 6675-6679

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i21/6675.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i21.6675

Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent inflammatory dysfunction first described by Rokitansky in 1860 and characterized by the presence of glands and stroma that histologically resemble functional endometrial tissue but are located outside of the uterus[1,2].

Endometriosis occurs in an estimated 1% to 20% of asymptomatic women, 10% to 25% of sterile patients and 60% to 70% of women with chronic pelvic pain. Different manifestations of this disorder have been described, such as endometriosis genitalis externa, adenomyosis externa, endometriosis extra-genitalis and deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE)[3].

Within the abdomen, endometriosis can be divided into intra- and extra-peritoneal disease. In decreasing order of frequency, the prevalent intra-peritoneal locations are the ovaries (30%), the utero-sacral and large ligaments (18%-24%), the fallopian tubes (20%), the pelvic peritoneum, Douglas’ pouch, the appendix and the small and large intestines. In contrast, it is uncommon to find endometriosis in an extra-peritoneal structure, such as the cervix (0.5%), vagina and recto-vaginal septum, the round ligament and inguinal hernia sac (0.3%-0.6%), the navel (1%), abdominal scars resulting from gynecological surgery (1.5%) and the abdominal rectus muscle (0.5%). Finally, endometriosis rarely affects extra-abdominal organs, such as the lungs, urinary system, skin and central nervous system[2].

Gastrointestinal involvement of endometriosis has been found in 3% to 37% of women, most commonly in the sigmoid colon, rectum, and terminal ileum[2,4]. Although bowel endometriosis may cause severe gastrointestinal symptoms, these disturbances are not often adequately investigated at the time of gynecologic evaluation[1]. As a result, bowel endometriosis may be an unexpected finding at the time of surgery.

Lymph node involvement in endometriosis is usually considered to be uncommon. However, some studies[5] emphasize that lymph node involvement in endometriosis might just be an underestimated event related to the minimal removal of tissues by surgeons.

We report a case of DIE with recto-sigmoid and paracolic lymph node involvement and compare our remarks with the current literature.

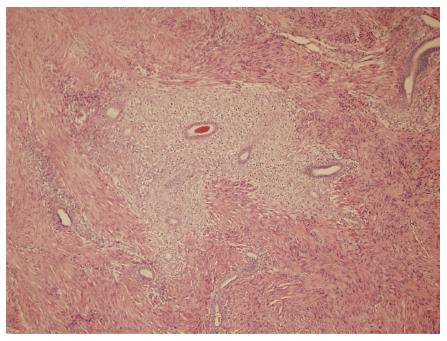

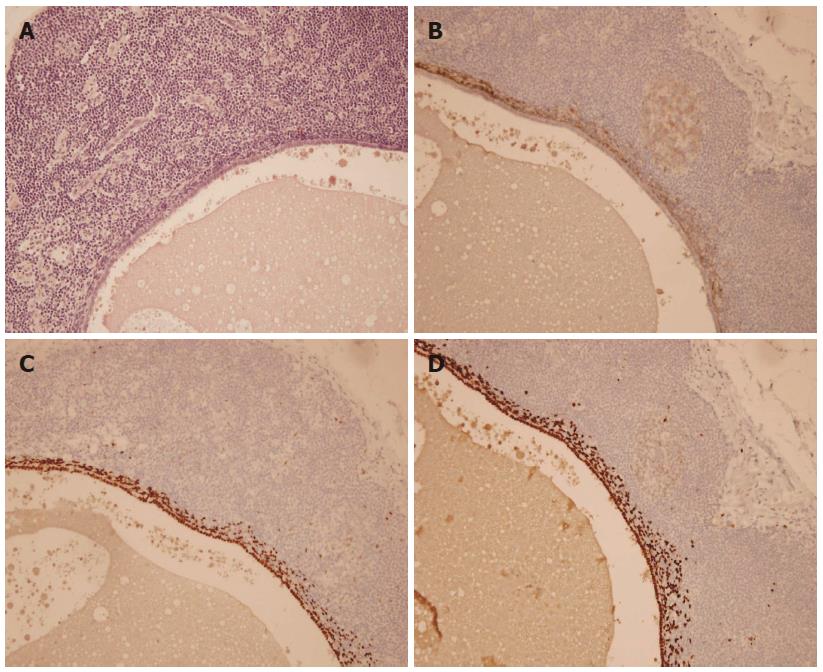

A nulliparous 37-year-old woman was referred to the general surgery department of our hospital in April 2012 for widespread abdominal pain associated with diarrhea and bloody stools. The patient had started to complain about the pain seven months earlier, in September 2011. Episodes of pain relapsed regularly every month, approximately three days after menstruation. Initially, the pain did not match the diarrhea and presence of blood in the feces, which both appeared only two months later (November 2011). In 2004, the patient had undergone exploratory laparoscopy with the removal of some endometrial cysts from both ovaries, the extra-pelvic abdominal peritoneum and the pouch of Douglas, resulting in a diagnosis of stage four endometriosis. A forced menopause via treatment with a GnRH agonist (Decapeptyl) was induced for one year. Between 2005 and 2011, the patient had four IVF attempts to become pregnant, all unsuccessful. During these attempts, she satisfactorily contained the symptomatology with an estroprogestinic pill. At the worsening of symptoms in November 2011, she consulted her gynecologist and underwent an abdominal ultrasound examination, revealing the presence of a 3 cm diameter node on the surface of the sigmoid colon suspected for endometriosis growth. A subsequent double-contrast barium enema highlighted a stenosis of the proximal tract of the sigmoid colon with an extrinsic compression on the medial wall, approximately 35 cm in length (Figure 1). An abdominal-pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), performed on January 31st, 2012, confirmed the presence of a node infiltrating the sigmoid colon wall approximately 17 cm from the pectinate line. MRI examination also revealed the presence of an adhesion between the sigmoid colon and an adjacent intestinal loop; a secondary subcentimetric nodule at the level of the recto-vaginal septum was also identified, with the same radiological aspects as the largest nodule. Finally, on April 6th, a colonoscopy performed to refine the diagnosis revealed the presence of an inflamed and hyperemic mucosa roughly 20 cm from the anus. Due to the stenosis, the examination was unable to reach the ileocecal valve. The biopsy only revealed the presence of inflammatory cells and edema. The physical examination prior to the operation showed mild diffuse abdominal tenderness and negative Blumberg’s sign. Auscultation detected normal bowel sounds and peristaltic rushes. Laboratory analysis revealed values of white blood cell 4.58 K/uL, hemoglobin 13.2 g/dL, carbohydratic antigen (CA)125 29.7 U/mL, CA15.3 14.3 U/mL, CA19.9 7.3 U/mL, and carcinoembryonic antigen 0.4 mg/mL; metabolic panel and liver function tests were within normal limits. The patient underwent laparoscopic surgery on May 2nd, 2012 during which a minimal left hemicolectomy was performed with the resection of only 7 cm of the sigmoid colon. Both radiologically described nodes were detected and removed during the surgical procedure. Another 1.5 cm node was revealed at the level of the utero-vesical fold during the operation (Figure 2). There was no evidence of adhesion between the sigmoid colon and the near intestinal loops as documented by MRI. The post-operative course was uneventful, and the patient left the hospital 5 d later. The evaluation of the excised specimen showed endometriosis involving the removed sigmoid colon tract and causing its convoluted course. Histological analysis revealed infiltration of the bowel wall (Figure 3), but the mucosa was not ulcerated. Endometriosis was evident in the serosa, the subserosa, the entire thickness of the muscularis propria and focally within the submucosa. The submucosa also showed diffuse congestion, fibrosis and focal clusters of hemosiderin-laden macrophages. All of the removed nodes were diagnosed as endometrial growths. Endometrial involvement, with a cystic glandular pattern, was also detected in a pericolic lymph node measuring 3 mm, as confirmed by immunohistochemical staining for CD10 and the estrogen and progesterone receptors (Figure 4). Approximately one year after the surgical operation (July 2013), the patient referred to her physician for an episode of constipation and pain associated with defecation. A transvaginal ultrasound examination performed in September 2013 revealed the presence of a cystic structure around the rectum and in the utero-vesical fold, strongly suspected for a relapse of the disease.

Endometriosis is a common condition that affects women during the reproductive years. It occurs when normal tissue from the uterine lining, the endometrium, attaches to other organs and starts to grow. This displaced endometrial tissue causes irritation in the pelvis, which may lead to pain and infertility. Experts do not understand why some women develop endometriosis. Although we know the factors potentially involved in the etiology and pathogenesis of endometriosis, the exact mechanism by which this disease develops, with its associated signs and symptoms, remains obscure. Nevertheless, it is recognized that three separate entities exist (peritoneal, ovarian, and recto-vaginal endometriosis) based on the different locations, possible origins, appearances and hormone responsiveness of all these lesions[6]. Several theories been developed to account for the pathogenesis of different implants, which can be divided into implants originating from the uterine endometrium and those arising from tissues other than the uterus[7,8]. The most widely accepted theory is the retrograde menstruation theory proposed by Sampson in 1920[8]. According to this theory, endometrial tissue refluxes through the fallopian tubes during menstruation, in turn implanting and growing on the serosal surface of the abdominal and pelvic organs. The usual anatomic distribution of endometriotic lesions also favors the retrograde menstruation theory[8]. Some authors[6,8,9] sustain that this theory is not sufficient to explain the origin of the so-called “deep endometriosis,” which includes recto-vaginal and infiltrative lesions involving vital structures such as the bowel, ureters, and bladder. Koninckx and Martin[9] were the first to define deep endometriosis, having distinguished posterior cul-de-sac and recto-vaginal lesions in three different subgroups: type I, conically shaped, developed from infiltration; type II, deeply located, covered by extensive adhesions, most likely formed by retraction; and type III, the most severe, having one or more spherical nodules located in the recto-vaginal septum with the largest size under the peritoneum, possibly to be considered as adenomyosis externa. As a matter of fact, these latter endometriosis growths should be considered a different entity than peritoneal endometriosis, likely with another pathogenesis. Since 1997, it has been suggested that these growths could correspond to an adenomyotic nodule originating from mullerian rests through a metaplastic process[7]; however, this hypothesis remains very disputed and is not universally shared[10]. Endometriosis usually occurs in the pelvic organs and peritoneum but rarely in the rectum, colon, small intestine, kidney, ureter, appendix, external female genital organs, lymphatic nodules or the surrounding area of the anus. Endometriosis infiltrates the bowel with a frequency of 5% to 37%[11] in the following order: rectum, sigmoid colon, appendix, ileum and cecum. Clinical symptoms of endometriosis include dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia and infertility, but the clinical presentation is often non-specific. DIE, especially if it involves the bowel, is often also associated with constipation or diarrhea, abdominal bloating, bowel movements and occasionally bloody stools. Symptoms are often cyclical but may become permanent when the lesion progresses. Furthermore, the symptoms are not always the same in each woman, and in some women with endometriosis, they are totally absent.

The status of the lymph nodes in endometriosis remains obscure or, more likely, underestimated. The greatest limit to their identification is that dissection is not usually performed for benign diseases. Noël et al[5] carefully studied 26 cases of recto-sigmoid endometriosis, finding lymph node involvement in 42.3% of the cases and demonstrating that lymph node involvement in the recto-sigmoid endometriosis should not be considered an uncommon occurrence. A shared hypothesis is that lymph node endometriosis represents a lymphatic drainage from endometriotic tissue. Similar to true malignant tumors, DIE, in particular the recto-sigmoid endometriosis, has an aggressive potential and ability to invade the adjacent tissue extensively with probable lymphovascular invasion. Endometriosis is considered a benign disease, but it occasionally becomes severe and progressive with a high rate of recurrence: endometriotic and cancer cells have similar characteristics, such as responsiveness to growth factors, resistance to antiproliferative factors, decreased apoptosis, the promotion of neoangiogenesis and metastatic potential[12].

Finally, there are numerous reported cases of malignancy arising from endometriotic deposits and substantial histologic evidence according to which endometriosis is associated with endometrioid carcinoma and clear cell carcinoma of the ovary[13]. At the present moment, there are many controversies regarding the therapeutic approach to DIE, in particular if bowel involvement is associated. In our case, the sigmoid resection was necessary due to the deep infiltration of the wall by the endometriosis lesion and the heavy symptomatology of the patient. Despite the fact that bowel resection has become a popular treatment modality, even with the improved operative laparoscopy techniques, many authors emphasize that an aggressive surgery for DIE involving a bowel resection is rarely justified[14]. In their studies on DIE, Acién et al[14] strongly suggest that the efficacy of an aggressive surgery may be lower than that of medical treatment. For instance, in the case of widespread disease with bowel involvement, nonaggressive sharing (NAS), with or without a hysterectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy (HBSO), followed by hormone replacement therapy may be considered a valid alternative to intestinal surgery. Indeed, it has been proven that surgery associated with post-operative hormone therapy can provide better results than an exclusively surgical or pharmacological treatment[15]. In general, these studies show that patients who undergo an aggressive operation have a worse outcome than those treated with NAS and/or HBSO. Nevertheless, these studies also underline the fact that NAS is deeply associated with a higher risk of recurrences and reoperations over the years: approximately 55% of patients experience a recurrence ,with approximately 38% needing a more extensive operation, versus patients treated with HBSO who experienced a follow-up free of recurrences[14]. In our case, the detection of the involved lymph node has been an infrequent event, proving, however, the existence of some possible endometriosis foci beyond the obvious ones. If the aim of surgery is to remove all areas of endometriosis, then it could appear irrational to remove only all visible foci when there is a high risk of associated lymph node involvement and/or of recurrence[5,16].

After these considerations, a more conservative type of surgery aimed at removing all visible endometriosis foci followed by pharmacological therapy could be the best choice to have a positive outcome, but it does not appear as good at reducing the risk of recurrence as a wide surgical operation. Only randomized studies of medical treatments with or without conservative surgery versus HBSO, alone or with bowel resection, will allow us to determine which option provides the best balance between patient satisfaction and the risk of disease recurrence.

A 37-year-old female with a history of deep infiltrating endometriosis presented with abdominal pain, diarrhea and blood in her feces.

Diffuse abdominal tenderness and negative Blumberg’s sign, auscultation with normal bowel sounds and peristaltic rushes.

Endometriosis, inflammatory bowel disease, cancer.

Double-contrast barium enema highlighted a stenosis of the proximal tract of the sigmoid colon, and abdominal-pelvic magnetic resonance imaging confirmed the presence of a node infiltrating the sigmoid colon wall previously detected by ultrasound examination and also revealed a secondary subcentimetric nodule at the level of the recto-vaginal septum.

All specimens surgically removed were diagnosed as endometriosis foci, with one of them infiltrating the sigmoid wall.

CD10, estrogen and progesterone receptors are immunohistochemical markers typically expressed by the endometrial stromal cells.

Conservative surgical treatment of only visible endometriosis foci, even followed by pharmacological therapy, might expose the patient to a higher risk of disease recurrence.

Based on the belief that finding a lymph node involved in endometriosis is uncommon, we reflected on the relevance of leaving undetected endometriosis foci behind after a surgical operation.

| 1. | Nezhat C, Hajhosseini B, King LP. Laparoscopic management of bowel endometriosis: predictors of severe disease and recurrence. JSLS. 2011;15:431-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | De Ceglie A, Bilardi C, Blanchi S, Picasso M, Di Muzio M, Trimarchi A, Conio M. Acute small bowel obstruction caused by endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3430-3434. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Mechsner S, Weichbrodt M, Riedlinger WF, Bartley J, Kaufmann AM, Schneider A, Köhler C. Estrogen and progestogen receptor positive endometriotic lesions and disseminated cells in pelvic sentinel lymph nodes of patients with deep infiltrating rectovaginal endometriosis: a pilot study. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:2202-2209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Insabato L, Pettinato G. Endometriosis of the bowel with lymph node involvement. A report of three cases and review of the literature. Pathol Res Pract. 1996;192:957-961; discussion 962. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Noël JC, Chapron C, Fayt I, Anaf V. Lymph node involvement and lymphovascular invasion in deep infiltrating rectosigmoid endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:1069-1072. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Nap AW, Groothuis PG, Demir AY, Evers JL, Dunselman GA. Pathogenesis of endometriosis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;18:233-244. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Nisolle M, Donnez J. Peritoneal endometriosis, ovarian endometriosis, and adenomyotic nodules of the rectovaginal septum are three different entities. Fertil Steril. 1997;68:585-596. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Burney RO, Giudice LC. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:511-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 995] [Cited by in RCA: 1090] [Article Influence: 77.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Koninckx PR, Ussia A, Adamyan L, Wattiez A, Donnez J. Deep endometriosis: definition, diagnosis, and treatment. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:564-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 272] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vercellini P, Frontino G, Pietropaolo G, Gattei U, Daguati R, Crosignani PG. Deep endometriosis: definition, pathogenesis, and clinical management. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2004;11:153-161. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Namkung J, Kim SJ, Kim JH, Kim J, Hur SY. Rectal endometriosis with invasion into lymph nodes. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37:1117-1121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bourdel N, Durand M, Gimbergues P, Dauplat J, Canis M. Exclusive nodal recurrence after treatment of degenerated parietal endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:2074.e1-2074.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Thomas EJ, Campbell IG. Evidence that Endometriosis Behaves in a Malignant Manner. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2000;50:2-10. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Acién P, Núñez C, Quereda F, Velasco I, Valiente M, Vidal V. Is a bowel resection necessary for deep endometriosis with rectovaginal or colorectal involvement? Int J Womens Health. 2013;5:449-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Alkatout I, Mettler L, Beteta C, Hedderich J, Jonat W, Schollmeyer T, Salmassi A. Combined surgical and hormone therapy for endometriosis is the most effective treatment: prospective, randomized, controlled trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20:473-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Abrao MS, Podgaec S, Dias JA, Averbach M, Garry R, Ferraz Silva LF, Carvalho FM. Deeply infiltrating endometriosis affecting the rectum and lymph nodes. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:543-547. [PubMed] |

P- Reviewers: Rubello D, Vinh-Hung V S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH