Published online Apr 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i14.4110

Revised: December 25, 2013

Accepted: January 20, 2014

Published online: April 14, 2014

Processing time: 215 Days and 20.7 Hours

Behçet’s disease is a chronic, relapsing, systemic vasculitis of unknown aetiology. Patients present manifestations of gastrointestinal complications, including mouth lesions, small and large intestinal lesions, and vascular lesions in the abdomen. In some cases, the intestinal ulcers of patients with Behçet’s disease are indistinguishable from those of Crohn’s disease, tuberculosis, vasculitis and other diseases. In this article, we present a case of atypical Behçet’s disease with a complicated medical history and multisystem damage, for the purpose of better management of this disease.

Core tip: Behçet’s disease is systemic inflammatory vasculitis of unknown aetiology. Its clinical manifestation of gastrointestinal complications varies greatly. Diagnosis is mainly based on typical clinical findings: no specific serum markers or pathological features are available. However, in clinical practice, it is often challenging to make a prompt and correct diagnosis when gastroenteropathy is presented as the initial or predominant manifestation in Behçet’s disease patients. The disease is sometimes misdiagnosed as inflammatory bowel disease or other disorders. We present a case of atypical Behçet’s disease with a complicated medical history and multisystem damage, for the purpose of better management of this disease.

- Citation: Yang XN, Ye ZS, Fan YY, Hu YQ. Prolonged small vessel vasculitis with colon mucosal inflammation as first manifestations of Behçet’s disease. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(14): 4110-4114

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i14/4110.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i14.4110

Behçet’s disease is systemic inflammatory vasculitis of unknown aetiology, characterized by a relapsing episode of oral aphthous ulcers, genital ulcers, cutaneous and ocular lesions, and other manifestations, including vascular, neurological, and gastrointestinal involvement[1].

The clinical manifestation of gastrointestinal complications also varies greatly, from mild symptoms to life-threatening complications, including perforation, infarction and massive bleeding resulting from vasculitis and/or thrombosis[2]. Prompt treatment with corticosteroids plus immunosuppressive agents, rather than surgery, can alleviate the clinical symptoms and improve the prognosis of Behçet’s disease patients. The diagnosis of Behçet’s disease is mainly based on typical clinical findings: no specific serum markers or pathological features are available. However, in clinical practice, it is often challenging to make a prompt and correct diagnosis when gastroenteropathy is presented as the initial or predominant manifestation of Behçet’s disease. The disease is sometimes misdiagnosed as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or other disorders. In this paper, we present a case of atypical Behçet’s disease with a complicated medical history and multisystem damage, for the purpose of better management of this disease.

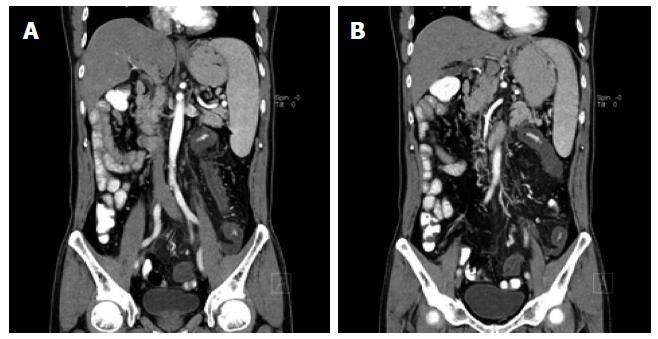

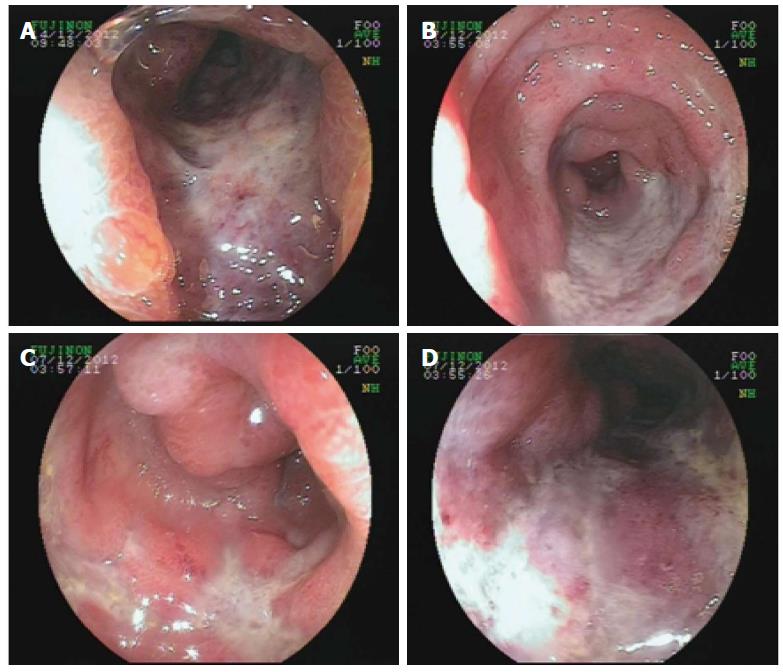

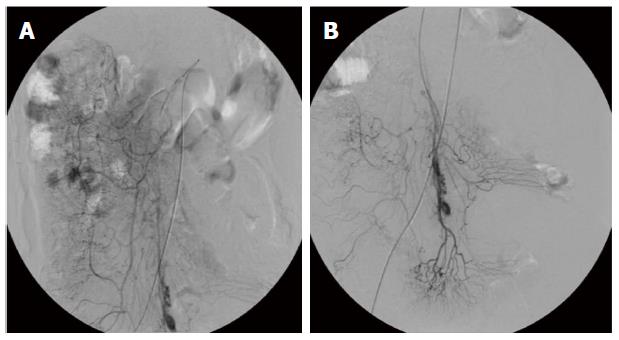

A 56-year-old Asian male presented to the department of gastroenterology complaining of acute-onset bloody diarrhoea for 2 h and generally feeling unwell, with abdominal pain accompanied by mushy stool for the last 3 mo. He described symptoms including pressure in the belly or abdominal pain, stool with mucous (over 10 times each day), progressive fatigue and dizziness. He had no fever, sweating, nausea, vomiting, rash, mucosal lesions, musculoskeletal problem or oral ulcer. Approximately 2 mo before admission, when the abdominal mass appeared, he was evaluated at the hospital. Laboratory findings were as follows: increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (22 mm/h); C-reactive protein (132 mg/dL); D-dimer (1972 mg/L); and CA19-9 (130.7 U/mL). Abnormal protein patterns in blood serum were found by serum protein electrophoresis (albumin 58%, α-globulin 3.6%, β-globulin 18.7%). Additional tests, including anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA), tuberculosis antibody and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), were within normal limits and the stool bacterial culture was negative. Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging revealed stenosis of the mesenteric inferior artery branch and thickening of the mesenteric inferior artery branch walls (Figure 1). A diffuse lesion of the left colon associated with inflammatory changes was also observed. A diagnosis of ischaemic bowel disease was made. He went to another hospital where colonoscopy was performed, which was suggestive of stenosis and stiffness of the left colon (Figure 2). Digital subtraction angiography of the superior mesenteric artery confirmed vascular malformation (Figure 3). An ultrasound scan of the scrotal sac showed changes consistent with hydrocele of the tunica vaginalis and epididymo-orchitis. He was given various diagnoses including congenital mesenteric vascular malformation, ischaemic bowel disease and herpes zoster. The patient was treated empirically to improve his circulation and with antivirus therapy, followed by treatment for nutritional support, which achieved remission of his symptoms. Two hours before admission, with acute-onset bloody diarrhoea, the patient came to our hospital and was admitted.

The patient had a history of surgery 6 years previously. On that occasion, he had complained of abdominal pain and haemafaecia. Acute intestinal obstruction was diagnosed; therefore, a partial resection of the ileum and anastomosis were performed. He had also received surgery for an ankle cyst and wrist tenosynovitis a few years ago. There was a family history of immune system diseases. His daughter has Mediterranean anaemia and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

Physical examination revealed a male in mild distress. Vital signs were normal and the lungs were clear to auscultation. A cardiac examination revealed normal heart sounds and no murmurs. The abdomen was soft. Other significant physical examination findings included a healed surgical scar at the site of previous abdominal operation on the midline, and on the left wrist and ankle for operations for ankle cyst and wrist tenosynovitis, respectively. There was a mass (3 cm × 4 cm) on deep palpation in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen. There was no lymph node enlargement and no oral, respiratory, cardiovascular, abdominal, neurological, musculoskeletal or genital abnormalities. The remainder of the examination was normal.

Initial studies included a general laboratory investigation, chest X-ray and electrocardiography (ECG). A blood test was normal except for platelet counts (57 × 109/L). Urinalysis showed a positive occult blood test and positive urobilinogen. Routine stool analysis found pus cells (0-1/Hp), red blood cells (1/Hp), and a defecate occult blood test was positive. Serological tests were performed and showed an increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (48 mm/h), C-reactive protein (12.2 mg/dL), and hyperbilirubinemia (TBIL: 23.4 μmol/L, DBIL: 7.2 μmol/L, IBIL: 16.2 μmol/L). Additional tests, including ANA, ENA, and ANCA antibodies, complement levels, human immunodeficiency virus antibodies, and hepatitis B and C serology, were within normal limits. The results of radiography of the chest and ECG were normal.

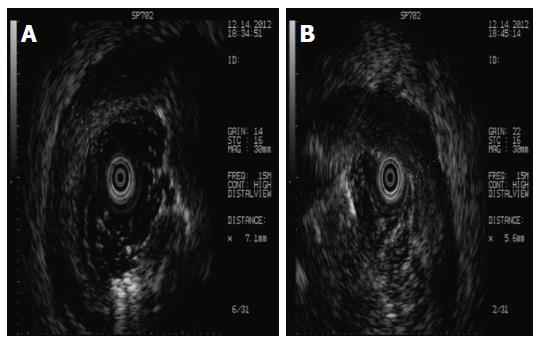

His bloody diarrhoea had diminished the following day, whereas his abdominal pain remained. Considering the history of recurrence of bloody diarrhoea, the colonoscopy was repeated. The endoscopic features, such as deep ulcer lesion, granulated tissue and lumenal stenosis in the sigmoid colon and rectum, raised suspicion of IBD. At this point, a differential diagnosis of intestinal ulcerations including infectious causes such as herpes simplex virus (HSV), tuberculosis, and acute HIV infection and non-infectious causes such as lymphoma, IBD, chronic deep tissue infection, occult solid organ malignancy, vasculitis, developing connective tissue disease, and Behçet’s disease was considered. Further investigation included ultrasound colonoscopy (Figure 4), which did not reveal any focal uptake. Sigmoid colon mucosal punch biopsy was performed, which demonstrated formation of granulated tissue, lymphoid hyperplasia, and infiltration of plasma cells, neutrophils, and monocytes into the mucosa. Increased blood vessels with hyaline degeneration and thickening vessel walls were observed. Lymphocytes surrounded the wall of the submucosal venules, especially in the deeper parts. Surgical pathological section of the partial resection of the ileum and anastomosis 6 years ago was studied again and the findings were similar to the present ones, which indicated vascular disruption and damage by neutrophil infiltration. These findings were consistent with vasculitis (Figure 5).

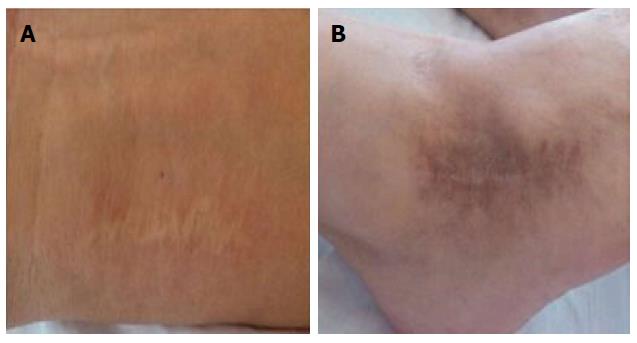

Until this point, progression of the patient’s symptoms was consistent with prolonged intestinal ischaemia and vascular damage. Biopsies confirmed the presence of vasculitis and, given the clinical context, he was diagnosed with Behçet’s disease, albeit without some typical features, such as oral and genital ulcers. We considered vascular inflammation to be related to vascular immune complex deposits, though small-vessel vasculitis could not be completely ruled out. Asking for the patient’s medical history, the wrist and ankle surgery also hinted at the patient having rheumatoid immune disease (Figure 6). The patient was given peroral methylprednisolone 40 mg and leflunomide 10 mg once daily, with quick resolution of his symptoms and disappearance of his abdominal mass.

Two months later, he was hospitalised with acute abdominal pain. A spontaneous sigmoid perforation was diagnosed and sigmoid resection with proximal colostomy was performed. When the use of glucocorticoids was discontinued, recurrent genital ulceration appeared. The patient was finally diagnosed with atypical Behçet’s disease and is now being treated with intravenous methylprednisolone at a dose of 20 mg and small doses of gamma globulin. The patient had a complicated hospital stay but responded well to intravenous glucocorticoids and was discharged in a stable condition.

Behçet’s disease is an inflammatory disorder of unknown cause, characterised by recurrent oral aphthous ulcers, genital ulcers, uveitis and skin lesions. All these common manifestations are self-limiting, except for the ocular attacks. Repeated attacks of uveitis can cause blindness. Behçet’s disease is not a chronic, persistent inflammatory disease, but rather comprises recurrent attacks of acute inflammation. Involvement of the gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system and large vessels is less frequent, although it can be life-threatening[3]. Susceptibility to Behçet’s disease is strongly associated with the presence of the HLA-B51 allele[3]. Environmental factors, such as infectious agents, have also been implicated in its pathogenesis.

Vascular injuries, hyperfunction of neutrophils and autoimmune responses are characteristic of Behçet’s disease. There are two forms of intestinal involvement: small vessel disease with mucosal inflammation causing ulcers; and large vessel disease resulting in intestinal ischaemia and infarction[4]. Mucosal ulceration is most commonly seen in the ileocaecal region, and was found in about 88% of patients in a recent study[4], usually on the antimesenteric side, followed by involvement of other parts of the colon, but rarely the rectum or anus. The ulcers may be aphthous or, alternatively, deep and round with a punched-out appearance. Longitudinal ulcers are rare.

Behçet’s disease does not have any pathognomonic symptoms or laboratory findings; therefore, diagnosis is made on the basis of the criteria proposed by the International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease in 2013[5]. According to the criteria, recurrent oral ulceration must be present, as well as at least two of the following: recurrent genital ulceration, eye lesions, skin lesions, and a positive pathergy test. The lesions recur and usually leave scars. The joints most frequently affected are the knees, followed by the wrists, ankles and elbows. Crohn’s disease (CD), tuberculosis, vasculitis and other diseases should be excluded before a diagnosis of Behçet’s disease is established[6]. Like CD, Behçet’s disease manifests as discrete ulcers and discontinuous bowel involvement with relative sparing of the rectum. The two diseases share extraintestinal manifestations, such as uveitis and arthritis. Unlike CD, Behçet’s disease is characterised by vasculitis of the small veins and venules, with deep ulcerations, generally without granulomas or cobblestoning. However, both diseases may have chronic nonspecific inflammation with normal intervening mucosa. Perforation is more common in Behçet’s disease than in CD, as the latter is characterised by intense fibrosis[7]. Scalloping, ulceronodular patterns and abscess formation are not observed in Behçet’s disease[7]. HLA typing may also be helpful in the differential diagnosis.

The choice of treatment depends on the patient’s clinical manifestations. Treatment is largely empirical because the heterogeneity of the disease and the unpredictable course with exacerbation and remission make well-controlled studies difficult to conduct. Therefore, there is a lack of evidence-based treatment recommended for the management of Behçet’s disease. Agents such as corticosteroids, sulphasalazine, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, tumour necrosis factor α antagonist, or thalidomide should be tried first before surgery, except in an emergency[8,9].

In conclusion, we describe a patient with gastrointestinal symptoms as primary manifestations of Behçet’s disease. Our case highlights the need for clinicians to broaden consideration of differential diagnoses, with particular attention to atypical features of Behçet’s disease.

P- Reviewers: Griglione N, Kane S, Vermeire S S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: Stewart G E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Sakane T, Takeno M, Suzuki N, Inaba G. Behçet’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1284-1291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1288] [Cited by in RCA: 1246] [Article Influence: 46.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Wu QJ, Zhang FC, Zhang X. Adamantiades-Behcet’s disease-complicated gastroenteropathy. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:609-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Mizuki N, Inoko H, Ohno S. Pathogenic gene responsible for the predisposition of Behçet’s disease. Int Rev Immunol. 1997;14:33-48. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Choi IJ, Kim JS, Cha SD, Jung HC, Park JG, Song IS, Kim CY. Long-term clinical course and prognostic factors in intestinal Behçet’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:692-700. [PubMed] |

| 5. | International Team for the Revision of the International Criteria for Behçet’s Disease (ITR-ICBD), Davatchi F, Assaad-Khalil S, Calamia KT, Crook JE, Sadeghi-Abdollahi B, Schirmer M, Tzellos T, Zouboulis CC, Akhlagi M, Al-Dalaan A, Alekberova ZS, Ali AA, Altenburg A, Arromdee E, Baltaci M, Bastos M, Benamour S, Ben Ghorbel I, Boyvat A, Carvalho L, Chen W, Ben-Chetrit E, Chams-Davatchi C, Correia JA, Crespo J, Dias C, Dong Y, Paixão-Duarte F, Elmuntaser K, Elonakov AV, Graña Gil J, Haghdoost AA, Hayani RM, Houman H, Isayeva AR, Jamshidi AR, Kaklamanis P, Kumar A, Kyrgidis A, Madanat W, Nadji A, Namba K, Ohno S, Olivieri I, Vaz Patto J, Pipitone N, de Queiroz MV, Ramos F, Resende C, Rosa CM, Salvarani C, Serra MJ, Shahram F, Shams H, Sharquie KE, Sliti-Khanfir M, Tribolet de Abreu T, Vasconcelos C, Vedes J, Wechsler B, Cheng YK, Zhang Z, Ziaei N. The International Criteria for Behçet’s Disease (ICBD): a collaborative study of 27 countries on the sensitivity and specificity of the new criteria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:338-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 670] [Cited by in RCA: 956] [Article Influence: 73.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kobayashi K, Ueno F, Bito S, Iwao Y, Fukushima T, Hiwatashi N, Igarashi M, Iizuka BE, Matsuda T, Matsui T. Development of consensus statements for the diagnosis and management of intestinal Behçet’s disease using a modified Delphi approach. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:737-745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Korman U, Cantasdemir M, Kurugoglu S, Mihmanli I, Soylu N, Hamuryudan V, Yazici H. Enteroclysis findings of intestinal Behcet disease: a comparative study with Crohn disease. Abdom Imaging. 2003;28:308-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hatemi G, Silman A, Bang D, Bodaghi B, Chamberlain AM, Gul A, Houman MH, Kötter I, Olivieri I, Salvarani C. EULAR recommendations for the management of Behçet disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1656-1662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 570] [Cited by in RCA: 470] [Article Influence: 26.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Hatemi G, Silman A, Bang D, Bodaghi B, Chamberlain AM, Gul A, Houman MH, Kötter I, Olivieri I, Salvarani C. Management of Behçet disease: a systematic literature review for the European League Against Rheumatism evidence-based recommendations for the management of Behçet disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1528-1534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |