Published online Apr 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i13.3698

Revised: December 10, 2013

Accepted: January 14, 2014

Published online: April 7, 2014

Processing time: 155 Days and 18 Hours

Ischemic colitis is the most common form of intestinal ischemia. It is a condition that is commonly seen in the elderly and among individuals with risk factors for ischemia. Common predisposing conditions for ischemic colitis are major vascular occlusion, small vessel disorder, shock, some medications, colonic obstructions and hematologic disorders. Ischemic colitis following colonoscopy is rare. Here, we report two cases of ischemic colitis after a routine screening colonoscopy in patients without risk factors for ischemia.

Core tip: Ischemic colitis following colonoscopy is rare and is predominantly involved at the sigmoid colon and splenic flexure. However, our two cases were found on the right side of the colon after a routine screening colonoscopy in patients without risk factors for ischemia. We believe these cases are interesting and instructive for gastroenterologists.

- Citation: Lee SO, Kim SH, Jung SH, Park CW, Lee MJ, Lee JA, Koo HC, Kim A, Han HY, Kang DW. Colonoscopy-induced ischemic colitis in patients without risk factors. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(13): 3698-3702

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i13/3698.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i13.3698

Ischemic colitis is the most common form of intestinal ischemia and accounts for 1 in 1000 hospitalizations[1]. Although more frequent in the elderly, younger patients may also be affected[2]. Clinically, ischemic colitis manifests as a spectrum of injuries from transient self-limited ischemia involving the mucosa and submucosa, which has a good prognosis, to acute fulminant ischemia with transluminal infarction, which may progress to necrosis and death. Colon ischemia was first described as being caused by the ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery during aortic reconstruction or colon resection[3,4], but it is now recognized to have many potential causes. Common predisposing conditions for ischemic colitis are major vascular occlusion, small vessel disorder, shock, some medications, colonic obstructions and hematologic disorders. However, very few cases have been reported following endoscopic examinations thus far[5,6]. Here, we present two cases of ischemic colitis following a routine screening colonoscopy in young patients with no risk factors.

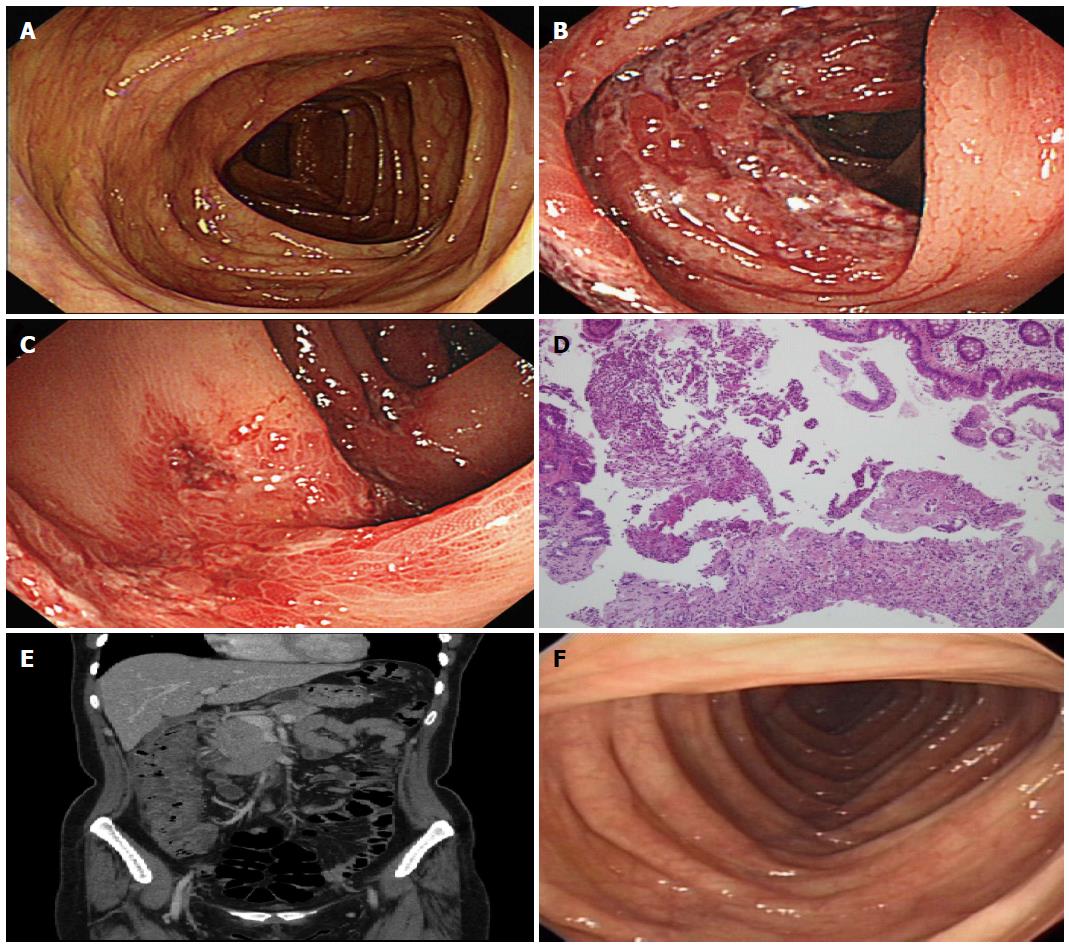

A 47-year-old woman presented to the emergency room complaining of abdominal pain with hematochezia 7 h after a routine screening colonoscopy in the primary clinic. She had no history of coagulopathy or embolic risk factors and a body mass index (BMI) of 22.3 kg/m2. The screening colonoscopic findings were normal (Figure 1A) except for a single colonic polyp in the transverse colon, which was removed by a forceps biopsy. The patient was prepared for the colonoscopy with a 4 L split-dose of polyethylene glycol, and the procedure itself had been uneventful with insufflations of room air during 13’36”. On admission, her initial blood pressure was 130/80 mmHg, and her heart rate was 70 beats per minute. Her abdomen was soft to palpation, with some tenderness on the right lower quadrant but no sign of peritonitis. The initial laboratory data showed elevated WBC 14.0 k/μL, but all other levels were normal, including HGB 13.2 g/dL and CRP 0.15 mg/dL. Stool cultures were negative, as was the hypercoagulable work-up. We believed minor bleeding had occurred at the biopsy site, but the bleeding quickly stopped. Therefore, we closely observed her conditions and vital signs with bowel rest, intravenous fluids and empirical antibiotics. Despite these measures, her abdominal pain and hematochezia persisted. On the next day, another colonoscopy showed severe submucosal hemorrhages with mucosal edema and longitudinal ulcers in the ascending colon (Figure 1B and C). The biopsy was compatible with findings of ischemic colitis and showed erosions and hemorrhages (Figure 1D). The possibility of bleeding from the forcep biopsy site was excluded by a complete colonoscopic examination. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans showed diffuse wall thickening of the ascending colon and fluid collection around the ascending colon (Figure 1E). The patient was managed supportively and resumed her diet on the 5th hospital day. She recovered uneventfully and was discharged on the 9th hospital day without complications. We performed a follow up colonoscopy after 6 mo and observed totally normal colonoscopic findings (Figure 1F).

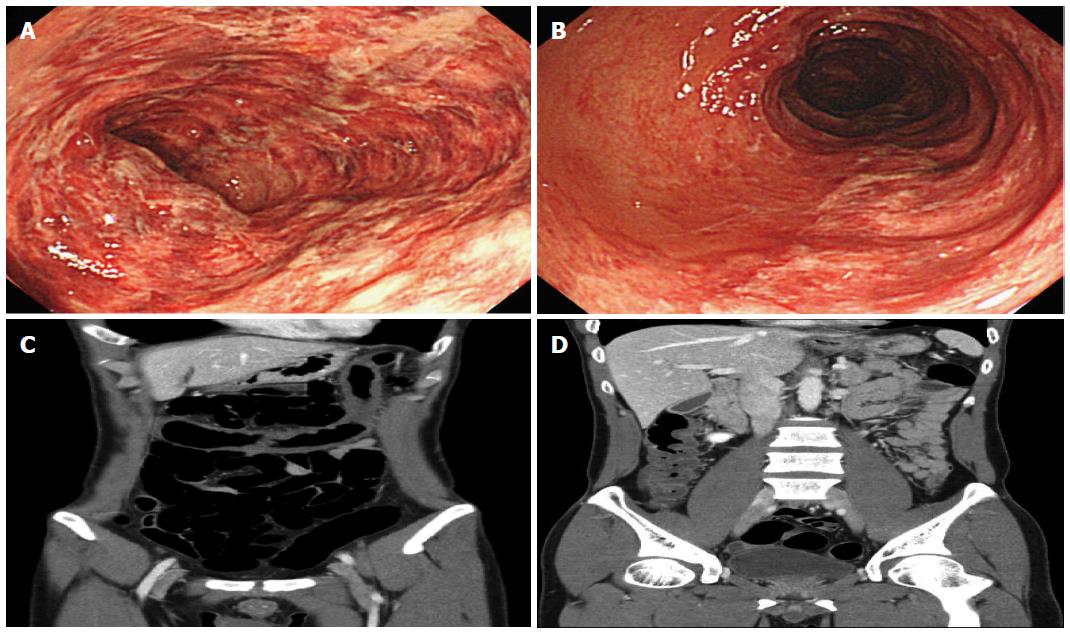

A 40-year-old man presented to the emergency room complaining of hematochezia with diffuse abdominal pain 18 hours after a routine screening colonoscopy in the primary clinic. He had no history of coagulopathy or embolic risk factors and a BMI of 19.8 kg/m2. The screening colonoscopic findings were normal. The patient was prepared for the colonoscopy with a 4 L split-dose of polyethylene glycol, and the procedure itself had been uneventful with insufflations of room air during 15’20”. On admission, his blood pressure was 130/80 mm/Hg, and his heart rate was 75 beats per minute. His abdomen was soft to palpation with moderate tenderness on the whole abdomen; however, there was no sign of peritonitis. The initial laboratory data showed an elevated WBC 17.43 k/μL and CRP 1.61 mg/dL, but all other data were normal, including HGB 14.8 g/dL. The stool cultures were negative, and a hypercoagulable work-up was not performed. We decided to perform a colonoscopy, but not above the distal transverse colon due to the patient’s pain and very friable colonic mucosa. Therefore, no biopsies were performed either. The colonoscopy showed diffuse edematous mucosal inflammations, submucosal hemorrhages, erosions and longitudinal ulcers with friability in the distal transverse colon and proximal sigmoid colon (Figure 2A and B). Abdomen CT scans showed submucosal edematous changes and decreased enhancement of thickened colonic wall from the ascending colon to the distal transverse colon (Figure 2C and D). The patient was also treated supportively with bowel rest, intravenous fluids and empirical antibiotics. He recovered without complications and was discharged on the 9th hospital day. We followed up in the outpatient department, and he complained of no symptoms.

Ischemic colitis is the most common form of intestinal ischemia. Although the incidence of ischemic colitis is increased in the elderly and among those with many with risk factors for vascular disease, an index lesion on angiography is unusual[2]. When present, abnormalities may include the narrowing of the small vessels and tortuosity of the long colic arteries[7]. Rather than a specific vascular lesion, there appears to be an acute, self-limited compromise in intestinal blood flow, which is inadequate for meeting the metabolic demands of the colon[8]. The colon is predisposed to ischemia by its relatively low blood flow compared with the rest of the gastrointestinal tract[9,10]. Experimental distension has been found to increase intraluminal pressure, reduce total blood and reduce the arteriovenous oxygen gradient in the colonic wall[11]. This most likely resembles the mechanism for the rare occurrence of ischemic colitis during colonoscopy or barium enema[6,12]. There are numerous conditions that predispose patients to ischemic colitis. The most common mechanism is hypotension from sepsis or impaired left ventricular function and hypovolemia from dehydration or hemorrhage, producing a compromise in systemic perfusion and triggering a reflex mesenteric vasoconstriction[2]. Numerous medications may produce colonic ischemia by a similar mechanism. The most common drugs are antihypertensive agents, diuretics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, digoxin, oral contraceptives, pseudoephedrine, cocaine and alosetron[2]. Predisposing factors for colonic ischemia in young adults include vasculitis, abdominal surgery, use of cocaine, oral contraceptive pills and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, hypercoagulable states, colonic obstruction and marathon running[13]. None of these risk factors were present in our cases.

Most patients present with the acute onset of mild, crampy abdominal pain and tenderness over the affected bowel. Within 24 h, there is usually passage of bright red or maroon blood often mixed with stool. Usually blood loss is minimal, without hemodynamic deterioration or the need for transfusion[2,9].

Any part of the colon may be affected, but (different pont size) the left colon is the predominant location in approximately 75% of patients[10]. Splenic flexure may be the most common site, as it is involved in one-quarter of patients[10], and isolated right colon ischemia occurs in approximately 10% of cases[13]. Because the rectosigmoid junction and splenic flexure may be vulnerable in systemic low-flow states due to the watershed area called Sudeck’s point, where the sigmoidal artery meets the superior colic artery, and Griffith’s point, where the mid-colic artery meets the left colic artery[14]. In our two cases, right colon ischemia developed. This incidence may be explained by the potentially increased vulnerability of the right colon to a systemic low-flow state, as the marginal artery of Drummond is poorly developed at this location in 50% of the population[15].

The diagnosis of ischemic colitis depends on characteristic findings in the appropriate clinical setting. Laboratory markers for ischemia, such as serum lactate, lactate dehydrogenase, alkaline phosphatase and metabolic acidosis, may be present, but they are uncommon. Plain abdominal films are insensitive and nonspecific, but they are important when excluding other disorders. A barium enema may show findings suggestive of ischemic colitis, such as thumbprinting, but this procedure is nonspecific and is present in many other infective or inflammatory colitis[16]. Abdominal computed tomography may show suggestive findings of ischemic colitis in up to 89% of patients. The most common finding is segmental circumferential wall thickening of affected colon[2].

Colonoscopy has largely supplanted the barium enema as the diagnostic modality of choice because of its higher sensitivity for detecting mucosal changes and its ability to obtain biopsy specimens if necessary. However, as there are no specific endoscopic findings for ischemic colitis, the clinical situations must be considered. Findings that favor ischemic colitis rather than inflammatory bowel disease are in segmental areas of injury, abrupt transition between normal and affected mucosa, rectal sparing and rapid resolution of mucosal changes on serial colonoscopy[2].

Treatment varies with the severity of the ischemia. In the absence of gangrene or perforation, supportive care is sufficient. Patients need bowel rest, intravenous fluid and often empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics to minimize bacterial translocation and sepsis.

Ischemic colitis following colonoscopy is comparatively rare. There have been 5 domestic cases of ischemic colitis after colonoscopy[14]. However, relatively young patients with no risk factors or those who prepare their bowels with polyethylene glycol was first noticed in this report. The causes of developing ischemic colitis following colonoscopy are damage to microvasculatures, mechanical compression, increased intraluminal pressure and hyperextension[17]. If the colonic intraluminal pressure rises up to 30-40 mmHg, reversible circulatory compromises may occur; however, if the intraluminal pressure rises above 50 mmHg, irreversible damages may occur[18]. In these cases, approximately 15 min encompassed the whole colonoscopic procedure, and no hyperextension or hyperinflation were performed. Ischemic colitis as a complication of colonoscopy is rare, but the incidence can increase when a prior history of intra-abdominal surgery, tortuous colon, longer procedure time or other risk factors of ischemia is present. Thus, we need to pay more attention to reducing colonoscopic procedure time, hyperinflation and hyperextension. Further, we should check the risk factors for ischemia and supply sufficient fluid to prevent the risk of ischemia before bowel preparation.

A 47-year-old woman and 40-year-old man without prior medical history presented with abdominal pain with hematochezia.

Their abdomen were soft to palpation, with tenderness on right lower quadrant (case 1) and whole abdomen (case 2) but no sign of peritonitis.

Infectious colitis, Inflammatory bowel disease, Diverticulitis, Colon cancer.

In the case 1, WBC 14.0 k/μL; HGB 13.2 g/dL; CRP 0.15 mg/dL and In case 2, WBC 17.43 k/μL; HGB 14.8 g/dL ; CRP 1.61 mg/dL; stool cultures were negative.

Abdominal computed tomography scans showed diffuse wall thickening of ascending colon and fluid collection around ascending colon (case 1) and submucosal edematous changes and decreased enhancement of thickened colonic wall from ascending colon to distal transverse colon (case 2).

Colonoscopic biopsy in case 1 was compatible with findings of ischemic colitis, showing erosions and hemorrhages.

The patients were treated supportively with bowel rest, intravenous fluids and empirical antibiotics.

It is unclear how colonoscopy induces ischemic colitis and our cases have right sided ischemic colitis and they do not have ischemic risk factors.

It is rare that ischemic colitis following colonoscopy is occurred in patients without risk factors of ischemia.

Awareness of the risk of this potential complication following colonoscopy in patients without risk factors of ischemia may lead to prompt diagnosis and effective treatment with improved outcome.

| 1. | Theodoropoulou A, Koutroubakis IE. Ischemic colitis: clinical practice in diagnosis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:7302-7308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Green BT, Tendler DA. Ischemic colitis: a clinical review. South Med J. 2005;98:217-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | SHAW RS, GREEN TH. Massive mesenteric infarction following inferior mesenteric-artery ligation in resection of the colon for carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1953;248:890-891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | SMITH RF, SZILAGYI DE. Ischemia of the colon as a complication in the surgery of the abdominal aorta. Arch Surg. 1960;80:806-821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Church JM. Ischemic colitis complicating flexible endoscopy in a patient with connective tissue disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:181-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cremers MI, Oliveira AP, Freitas J. Ischemic colitis as a complication of colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 1998;30:S54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Binns JC, Isaacson P. Age-related changes in the colonic blood supply: their relevance to ischaemic colitis. Gut. 1978;19:384-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tendler DA. Acute intestinal ischemia and infarction. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 2003;14:66-76. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Reinus JF, Brandt LJ, Boley SJ. Ischemic diseases of the bowel. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1990;19:319-343. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Gandhi SK, Hanson MM, Vernava AM, Kaminski DL, Longo WE. Ischemic colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:88-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Boley SJ, Agrawal GP, Warren AR, Veith FJ, Levowitz BS, Treiber W, Dougherty J, Schwartz SS, Gliedman ML. Pathophysiologic effects of bowel distention on intestinal blood flow. Am J Surg. 1969;117:228-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Versaci A, Macrì A, Scuderi G, Bartolone S, Familiari L, Lupattelli T, Famulari C. Ischemic colitis following colonoscopy in a systemic lupus erythematosus patient: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:866-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Brandt LJ, Boley SJ. Colonic ischemia. Surg Clin North Am. 1992;72:203-229. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Lee KW, Han KH, Kang JW, Lee JH, Jang KH, Kim YD, Kang GH, Cheon GJ. Two cases of ischemic colitis after colonoscopy. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;41:364-367. |

| 15. | Elder K, Lashner BA, Al Solaiman F. Clinical approach to colonic ischemia. Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76:401-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Iida M, Matsui T, Fuchigami T, Iwashita A, Yao T, Fujishima M. Ischemic colitis: serial changes in double-contrast barium enema examination. Radiology. 1986;159:337-341. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Lee BO, Choi H, Kang IJ, Kim KY, Lee HI, Kim JP, Lee BI, Kim BW, Cho SH, Choi KY. A case of ischemic colitis following colonoscopy. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;27:162-165. |

| 18. | Park JE, Moon W, Nam JH, Kim NH, Kim SH, Park MI, Park SJ, Kim KJ. [A case of ischemic colitis presenting as bloody diarrhea after normal saline enema]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2007;50:126-130. [PubMed] |

P- Reviewers: Iijima H, Meucci G, Naito Y S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH