Published online Apr 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i13.3663

Revised: January 27, 2014

Accepted: February 26, 2014

Published online: April 7, 2014

Processing time: 221 Days and 0.2 Hours

AIM: To study statements and recommendations on psychosocial issues as presented in international evidence-based guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD).

METHODS: MEDLINE, guidelines International Network, National Guideline Clearing House and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence were searched from January 2006 to June 30, 2013 for evidence-based guidelines on the management of IBD.

RESULTS: The search yielded 364 hits. Thirteen guidelines were included in the review, of which three were prepared in Asia, eight in Europe and two in the United States. Eleven guidelines made statements and recommendations on psychosocial issues. The guidelines were concordant in that mental health disorders and stress do not contribute to the aetiology of IBD, but that they can influence its course. It was recommended that IBD-patients should be screened for psychological distress. If indicated, psychotherapy and/or psychopharmacological therapy should be recommended. IBD-centres should collaborate with mental health care specialists. Tobacco smoking patients with Crohn’s disease should be advised to quit.

CONCLUSION: Patients and mental health specialists should be able to participate in future guideline groups to contribute to establishing recommendations on psychosocial issues in IBD. Future guidelines should acknowledge the presence of psychosocial problems in IBD-patients and encourage screening for psychological distress.

Core tip: A search of the literature found 13 evidence-based guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). Three guidelines were prepared in Asia, eight in Europe and two in the United States. Mental health care specialists participated in establishing six guidelines and representatives of patient support groups participated in establishing seven guidelines. Eleven guidelines made statements and recommendations on psychosocial issues. The guidelines were concordant in that mental health disorders and stress do not contribute to the aetiology of IBD, but they can influence its course. IBD-patients should be screened for psychological distress. If indicated, psychotherapy and/or psychopharmacological therapy should be recommended.

- Citation: Häuser W, Moser G, Klose P, Mikocka-Walus A. Psychosocial issues in evidence-based guidelines on inflammatory bowel diseases: A review. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(13): 3663-3671

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i13/3663.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i13.3663

Psychosocial issues are a significant dimension of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), chronic conditions of the gastrointestinal tract with an unknown aetiology and unpredictable course. Two main subtypes of IBD are Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). A systematic review of qualitative studies exploring the phenomenon of living with IBD demonstrated a highly negative impact of the disease on the overall quality of life[1]. In the European Federation of Crohn’s and Ulcerative Colitis Associations (EFCCA) patient survey (n = 5576 participants), 75% of patients reported that symptoms affected their ability to enjoy leisure activities and 69% felt that symptoms affected their ability to perform at work[2]. In a survey of the French association of IBD patients (n = 1663), 12% of IBD patients reported depression and 41% reported anxiety[3]. Other studies reported that as many as 75% of IBD patients believe that stress is a major contributor to the development of their disease and up to 90% of patients believe that stress triggers flares of their disease[4-6]. In the recent study, 30% of patients (of n = 302) expressed the need for psychological interventions[7] while in another paper it was demonstrated that 60% of IBD patients did not receive adequate help for their psychological problems[8].

The importance of psychosocial issues as perceived by individual patients is also supported by cohort studies with IBD populations. There is a strong evidence for the high comorbidity of anxiety and depression with IBD, indicating also that the symptoms of these mental health conditions are more severe during periods of active IBD and that the course of the disease worsens in depressed patients[9]. Health-related quality life in IBD-patients is not only negatively affected by disease activity but also by depression[10] and psychological distress has been found to be associated with non-adherence to medical treatment[11]. A recent systematic review demonstrated that 13 of 18 prospective studies reported significant relationships between stress and adverse outcomes in IBD[12].

Evidence-based guidelines gain growing recognition in providing patients and physicians with recommendations on diagnosis and treatment of the most frequent clinical situations based on the best available knowledge. Given the importance of psychosocial issues in IBD for the disease prognosis and management, this systematic review aims to assess the role of psychosocial issues in the course of IBD and explore the recommendations on the diagnosis and treatment of psychosocial problems as presented in the recent international evidence-based guidelines on the management of IBD.

Methods of the analysis and the inclusion criteria for the present study were specified in advance. The review followed the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration for systematic reviews of systematic reviews[13].

Types of guidelines: We selected evidence-based guidelines on the management of IBD (UC and/or CD) which included: (1) a systematic search and analysis of the literature; and (2) a structured consensus (informal and/or Delphi process and/or consensus development conference and/or nominal group technique) to build recommendations.

We excluded evidence-based guidelines which: (1) focussed on single diagnostic (e.g., screening for colorectal cancer) or therapeutic procedures (e.g., biologicals) or special situations (e.g., severe ulcerative colitis); and (2) were only based on expert consensus and/or a narrative search of the literature.

Types of outcome measures: We included any statements and recommendations on psychosocial issues in IBD. The following psychosocial issues were considered to be relevant: psychological distress (anxiety, depression), stress (daily hassles, major life events), coping, health-related quality of life, psychological diagnostics, psychological therapies, psychotherapy, psychopharmacological therapies. We assessed whether the evidence level (EL) of statements or recommendations was reported by the guidelines.

The electronic bibliographic databases screened included MEDLINE, guidelines International Network, National Guideline Clearing House and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) from January 2006 to June 30, 2013. We did not search for guidelines published before 2006, because evidence-based guidelines need to be updated regularly and this review was concerned with the most up-to-date evidence. The search strategy for MEDLINE followed the recommendation of the Association of the Medical Scientific Societies in Germany to identify evidence-based guidelines[14]. The search strategy for PubMed is outlined in Table 1. The search strategy was adapted for each database if necessary. No language restrictions were made. In addition, reference sections of evidence-based guidelines on the management of IBD were screened manually.

| To locate guidelines |

| 1 "Practice guidelines as topic"[MESH] |

| 2 "Practice guideline"[Publication type] |

| 3 "Consensus development conferences as topic"[MESH] |

| 4 "Consensus development conferences, NIH as topic"[MESH] |

| 5 "Consensus development conference, NIH "[Publication type] |

| 6 "Consensus development conference "[Publication type] |

| 7 or 1-6 |

| To locate IBD |

| 8 “Inflammatory bowel disease [MESH]” |

| 9 “Colitis, ulcerative [MESH]” |

| 10 “Crohn Disease [MESH]” |

| 11 or 8-9 |

| 12, 7 and 11 |

Two authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of potentially eligible studies identified by the search strategy detailed above (WH, AMW). The full text articles were then examined independently by two authors to determine if they met the inclusion criteria (WH, AMW). Discrepancies were rechecked and consensus achieved by discussion. If needed, a third author reviewed the data to reach a consensus (GM).

Two authors independently extracted the data using standard extraction forms (WH, AMW). Discrepancies were rechecked and consensus achieved by discussion. If needed, a third author reviewed the data to reach a consensus (GM).

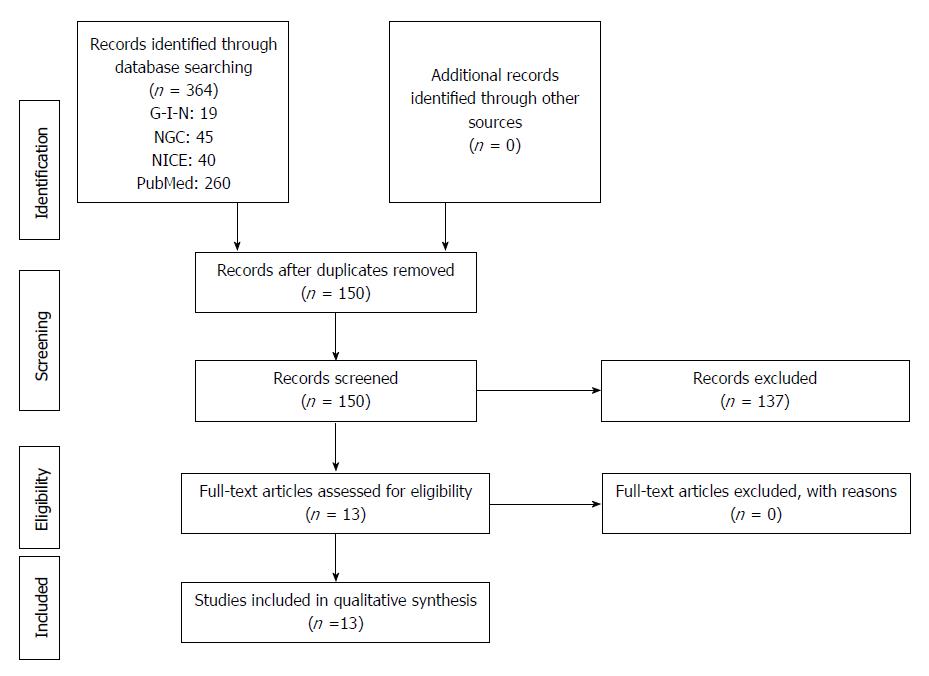

The search of the literature yielded 364 hits. One hit (guideline of the Finnish Society of Gastroenterology) was not available by libraries or the website of the Finnish Society of Gastroenterology. Thirteen guidelines were included into the review after screening of full papers (Figure 1). Three guidelines were prepared in Asia, eight in Europe and two in the United States. Three guidelines were on IBD and five each on UC and CD. The composition of the guidelines groups are outlined in Table 2. The methods used in the guideline process are outlined in Table 3.

| Organization | Country/continent | Year | Type of IBD | Guideline group (number of persons, specialties) |

| Asia Pacific Working Group on inflammatory bowel diseases | Asia | 2013 | IBD | Number not reported: Gastroenterologist, pathologist, colorectal surgeon, pharmacist, nurse, patient support group representative |

| NICE | United Kingdom | 2013 | UC | 13: Gastroenterologist, surgeon, pharmacist, nurse, general practitioner, psychiatrist, patient support group representative |

| ECCO | Europe | 2013 | UC | 35: Gastroenterologist, surgeon, psychosomatic medicine |

| Japanese Society of Gastroenterology | Japan | 2013 | CD | 18: Gastroenterologist, surgeon, general internal medicine |

| NICE | United Kingdom | 2012 | CD | 19: Gastroenterologist, colorectal surgeon, pharmacist, nurse, dietician, health economist, patient support group representative |

| British Society of Gastroenterology | United Kingdom | 2011 | IBD | 11: Gastroenterologist, surgeon, pediatrist |

| Asia Pacific Working Group on IBD | Asia and Australia | 2010 | UC | 28: Gastroenterologist, colorectal surgeon, pathologist, pharmacist, nurse practitioners, patient support group representatives |

| German Society of Gastroenterology | Germany | 2011 | UC | 71: Gastroenterologist, colorectal surgeon, pathologist, dietician, psychosomatic medicine, patient support group representative |

| Dutch Society for Gastroenteroolgy | 2010 | Number not reported: Gastroenterologist, general practitioner, psychologist, internist, dietician, pharmacist, occupational medicine, surgery, gynecologist, pathologist, radiologist, nurses, patients | ||

| American College of Gastroenterology | USA | 2010 | UC | No detailed information |

| American College of Gastroenterology | USA | 2010 | CD | 30: No detailed information |

| German Society of Gastroenterology | Germany | 2011 | CD | 49: Gastroenterologist, colorectal surgeon, pathologist, dietician, psychosomatic medicine, patient support group representative |

| ECCO | Europe | 2007 | CD | 25: Gastroenterologist, surgeon, psychosomatic medicine |

| Organization | Country/continent | Year | Type of IBD | Databases used | Searches until | Type of consensus |

| Asia Pacific Working Group on inflammatory bowel diseases | Asia | 2013 | IBD | English language publications in MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Trials Register in human subjects. All national and international guidelines on Ulcerative Colitis were solicited | Not reported | Modified Delphi process Canadian task force Grade A-E |

| NICE | United Kingdom | 2013 | UC | MEDLINE, Embase, Cinahl and the Cochrane Library | 15th November 2012 | Meta-analyses, grading the quality of evidence Evidence tables Formal consensus |

| ECCO | Europe | 2013 | UC | Medline, Central | December, 2010 | Delphi process and structured consensus |

| Japanese Society of Gastroenterology | Japan | 2013 | CD | MEDLINE, the Cochrane Library, and the Japan Medical Abstracts Society | Up to 2007 | Delphi process and structured consensus |

| NICE | United Kingdom | 2012 | CD | MEDLINE, Embase, Cinahl and The Cochrane Library | 13th March 2012 | Meta-analyses, grading the quality of evidence Evidence tables Formal consensus |

| British Society of Gastroenterology | United Kingdom | 2011 | IBD | PubMed, Medline and the Cochrane database | No details reported | Informal committee consensus |

| German Society of Gastroenterology | Germany | 2011 | UC | Medline, Central, PsycInfo | Until May 2009 | Structured consensus process |

| Asia Pacific Working Group on IBD | Asia and Australia | 2010 | UC | English language publications in MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Trials Register in human subjects. All national and international guidelines on Ulcerative Colitis were solicited | No details reported | Modified Delphi process |

| Dutch Society for Gastroenterology | 2010 | Central, Medline, PsychInfo | 2007 | Modified Delphi process | ||

| American College of Gastroenterology | United States | 2010 | UC | Medline | No details reported | Informal consensus |

| American College of Gastroenterology | United States | 2010 | CD | Medline | No details reported | Informal consensus |

| German Society of Gastroenterology | Germany | 2011 | CD | Medline, Central, PsycInfo | Until April 2007 | Structured consensus process |

| ECCO | Europe | 2007 | CD | Medline, Central | No details reported | Delphi process and structured consensus |

We present the statements and recommendations of the guidelines in the chronological order.

NICE guidelines on UC published in 2013 gave two recommendations on information provided to patients which should include impact of IBD on sexual functions, lifestyle, psychological wellbeing and sources of support and advice to be given before and after surgery (no EL reported). The NICE guidelines did not comment on psychological therapies in the summary of the topics which the guideline does not cover[15].

European Crohn’s Colitis Organization (ECCO) guidelines on UC published in 2013 included three statements on the impact of psychosocial factors on the disease, three recommendations on psychosocial diagnostics and two statements on psychological treatment (Table 4)[16].

| 1 There is no conclusive evidence for anxiety, depression and psychosocial stress contributing to risk for UC onset (EL2) |

| 2 Psychological factors may have an impact on the course of UC. Perceived psychological stress (EL2) and depression (EL2) are risk factors for relapse of the disease. Depression is associated with low health-related quality of life (EL3). Anxiety is associated with non adherence with treatment (EL4) |

| 3 Psychological distress and mental disorder are more common in patients with active ulcerative colitis than in population-based controls, but not in patients in remission (EL3) |

| 4 Clinicians should particularly assess depression among their patients with active disease and those with abdominal pain in remission (EL2) |

| 5 The psychosocial consequences and health- related quality of life of patients should be taken into account in clinical practice at regular visits (EL3). Patients' disease control can be improved by combining selfmanagement and patient-centred consultations (EL1b) |

| 6 Physicians should screen patients for anxiety, depression and need for additional psychological care and recommend psychotherapy if indicated (EL2). Patients should be informed of the existence of patient associations (EL 5) |

| 7 Psychotherapeutic interventions are indicated for psychological disorders and low quality of life (EL1) |

| 8 The choice of psychotherapeutic method depends on the psychological disturbance and should best be made by specialists (Psychotherapist, Specialist for Psychosomatic Medicine, Psychiatrist). Psychopharmaceuticals should be prescribed for defined indications (EL5) |

The Japanese guidelines on CD published in 2013 made one statement on HRQOL and gave three recommendations on life style modification: (1) in the active phase of the disease, patients face restrictions of social activities, such as school or work, due to treatment or hospitalization (no EL reported); (2) upon diagnosis, the patient with CD should quit smoking (EL3); (3) patients should be advised to avoid irregular lifestyle and eating habits, and to refrain from excessive alcohol drinking (no EL reported); and (4) patients should be advised to adopt a lifestyle without excessive mental stress, to have as little stress as possible (no EL reported)[17].

NICE guidelines on CD published in 2012 gave two recommendations on treatment decisions including psychosocial issues. If appropriate, age-appropriate multidisciplinary (gastroenterologist, surgeon, IBD-nurse specialist) support to deal with any concerns about the disease and its treatment, including concerns about body image, living with a chronic illness, and attending school and higher education should be offered. If appropriate, information, advice and support in line with published NICE guidance on smoking cessation and patient experience should be given. No levels of evidence were reported for these recommendations. The guidelines did mention psychological therapies in the summary of the topics which the guideline does not cover. However, mental health specialists were not mentioned in the context of the multidisciplinary team[18].

British Society of Gastroenterology Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults published in 2011 included two statements and three recommendations on psychosocial issues (Table 5)[19].

| 1 The essential supporting services to which the IBD team should have access should include a psychologist/counsellor (no EL reported) |

| 2 Stress and adverse life events do not appear to trigger the onset of Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, but most reports indicate that they may be involved in triggering relapse of IBD. Furthermore, behaviour limiting exposure to stressful situations is associated with reduced symptomatic relapse, at least in Crohn’s disease (no EL reported) |

| 3 Evidence indicates that psychosocial support is useful, particularly in adolescents. There is no definitive evidence that psychological interventions improve the course of IBD itself but they do usually improve patients’ quality of life and wellbeing (no EL reported) |

| 4 Psychological support should be available to patients with IBD (no EL reported) |

The German Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on UC published in 2011 included three statements on the impact of psychosocial factors on the disease, three recommendations on psychosocial diagnostics and two statements on psychological treatment (Table 6)[20].

| 1 Adverse life events, psychological stress and mental health disorders are not aetiologically linked to the onset of UC (EL2) |

| 2 Subjective stress and affective disorders may have a negative impact on the course of UC |

| 3 High disease activity is associated with high psychological symptom burden EL2) |

| 4 Mental health disorders have a negative impact on the course of the disease and quality of life EL2) |

| 5 Patients with persistent abdominal pain or diarrhea which cannot be explained by disease activity or complications of the disease should be assessed for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or depressive disorder. If IBS or depressive disorder is diagnosed, these disorders should be treated according to guideline recommendations (EL2) |

| 6 Psychosocial co-morbidities and health- related quality of life (accounting for gender differences) should be taken into account in clinical practice at regular visits (EL2) |

| 7 Care should involve cooperations with specialists in psychotherapy or psychosomatic medicine (EL2) |

| 8 Physicians should inform patients about IBD self-help organisations (EL5) |

| 9 In the case of a mental health disorder, psychotherapy is recommended (EL2) |

| 10 Psychosocial support should be offered to children and adolescents (EL1) |

The Asia-Pacific consensus statements on UC published in 2010 did not include any statement or recommendations on psychosocial issues[21].

The American College of Gastroenterology ulcerative colitis practice guidelines published in 2010 did not include any statements or recommendations on psychosocial issues[22].

The Dutch practice guidelines on Diagnostics and treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases for adults published in 2010 gave three statements on the impact of psychosocial factors on the disease and five statements on psychological treatment (Table 7)[23].

| 1 Personality traits do not contribute to the aetiology of IBD1 |

| 2 Psychosocial factors such as stress, depression/anxiety and coping have an impact on the course of IBD1 |

| 3 Health-related quality of life is influenced by disease activity but also by stress, anxiety/depression, social support and quality of treatment1 |

| 4 A positive relationship between patients and health care professionals characterized by mutual respect, communication, education and emotional support for patients and families is recommended1 |

| 5 Psychosocial problems associated with the disease should be treated by psychological interventions, e.g., stress management training, self-empowerment, cognitive-behavioural therapy1 |

| 6 Anxiety and depression should be treated according to appropriate guidelines |

| 7 IBD-patients who smoke should be advised to quit smoking1 |

ECCO guidelines on CD published in 2010 included three statements on the impact of psychosocial factors on the disease, three recommendations on psychosocial diagnostics and two statements on psychological treatment (Table 8)[24].

| 1 Psychological disturbances seem to be a consequence of the illness rather than the cause or specific to Crohn’s disease (EL1). The degree of psychological distress correlates with the disease severity (EL2) |

| 2 An association between psychological factors and the aetiology of Crohn’s disease is unproven (EL3), but there is a moderate influence on the course of the disease (EL1) |

| 3 Depression and perceived chronic distress seem to represent further risk factors for relapse of the disease (EL1). It remains unclear whether acute life events trigger relapses (EL1). Most patients consider stress to have an influence on their illness (EL2) |

| 4 Physicians should assess the patient’s psychosocial status and request additional psychological care and psychotherapy if indicated. Integrated psychosomatic care should be provided in IBD centres (EL2) |

| 5 Patients should be informed of the existence of patient associations (EL5) |

| 6 The psychosocial consequences and health related quality of life of patients should be taken into account in clinical practice at regular visits (EL1) |

| 7 Psychotherapeutic interventions are indicated for psychological disorders, such as depression, anxiety, reduced quality of life with psychological distress, as well as maladaptive coping with the illness (EL1) |

| 8 The choice of psychotherapeutic method depends on the psychological disturbance and should best be made by specialists (psychotherapist, specialist in psychosomatic medicine, psychiatrist). Psycho-pharmaceuticals should be prescribed for defined indications (EL5) |

The American College of Gastroenterology Crohn’s disease practice guidelines published in 2009 included one statement on psychosocial issues: Although many patients (and family members) are convinced that stress is an important factor in the onset or course of illness, it has not been possible to correlate the development of disease with any psychological predisposition to or exacerbations of stressful life events. No levels of evidence were reported for this statement[25].

The German Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on CD published in 2008 included three statements on the impact of psychosocial factors on the disease, three recommendations on psychosocial diagnostics and three statements on psychological treatment (Table 9)[26].

| 1 Mental health disorders are the sequelae rather than the cause of CD. Psychological distress is correlated with disease activity and has an impact on health-related quality of life and course of the disease (EL2) |

| 2 Psychosocial factors (personality traits, adverse life events, daily hassles) do not contribute to the etiology of CD (EL4) |

| 3 Depression, anxiety and perceived stress are risk factors for flares. It is not certain whether acute adverse life events trigger flares (EL3). Most patients believe that stress has an impact on the disease (EL4) |

| 4 The psychosocial consequences and health- related quality of life of patients (accounting for gender differences) should be taken into account in clinical practice at regular visits (EL5) |

| 5 Physcians should assess the psychosocial status of patients and their need for psychotherapy. If indicated, psychotherapy should be provided. IBD-centers should provide an integrated psychosomatic care EL2) |

| 6 Patients should be informed on the existence of patient organisations and selfhelp groups (EL5) |

| 7 Psychotherapy is indicated in the case of mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression, reduced health-related quality of life with psychological distress and maladaptive coping (EL2) |

| 8 The choice of a psychotherapeutic method depends on the psychological disturbance and should best be made by a psychotherapist. The choice of psychopharmacotherapy should be at the discretion of a psychiatrist specialist in the case of comorbid mental health disorders (e.g., depression and anxiety) (EL5) |

| 9 The increased risk of a mental health disorder is associated with an early manifestation of the disease. If needed, psychosocial support should be offered to the patient and their families (EL5) |

| 10 Patients using tobacco products should be encouraged to quit smoking (EL2) |

There is a growing body of evidence demonstrating the role of stress, anxiety and depression in IBD presentation and progression[9,12,27,28]. Evidence-based guidelines are increasingly becoming the major source of recommendations on diagnosis and treatment not only in IBD but also in other conditions and that is why it is important that problems of clinical significance (such as the role of psychosocial issues in IBD management) are included and commented on in the guidelines. This is the first review which has summarised current guidelines on the management of IBD with respect to psychosocial issues.

The most striking observation arising from this review was that as many as 10 out of 13 guidelines provided comments on the psychosocial issues demonstrating the recognition of their importance in IBD management. However, the published guidelines differed in the inclusion of psychosocial topics, particularly between Asia/Pacific, Europe and the United States, with European guidelines more likely to discuss the issue. In the cases where psychosocial issues were included in the guidelines, the statements and recommendations were similar between the countries. ECCO[16,24], Dutch[23] and German guidelines[20,26] made the most extensive statements and recommendations on psychosocial issues. In contrast, three guidelines[15,21,22] did not include any statements or recommendations on psychosocial issues. Seven guidelines included patient representatives[15,17,18,20,21,26]. However, the composition of the guidelines group (i.e., types of professionals involved and/or inclusion of patients) did not affect the role of psychosocial issues in the guideline. Importantly, only six guidelines included comments regarding mental health specialists[15,16,20,23,24,26].

The major statements and recommendations on psychosocial issues were as follows: (1) psychosocial factors such as mental disorders or stress do not play a role in the aetiology of IBD[15,19,20,23-26]; (2) psychosocial factors such as mental health disorders or stress may have a negative impact on the course of IBD[15,19,20,23,24,26]; (3) physicians should screen IBD-patients for psychological distress and the psychological care recommended when required[15,19,24,26]; (4) if indicated, psychosocial care (psychotherapy, psychopharmacotherapy) should be offered[15,19,20,23,24,26]; (5) IBD-centres should collaborate with mental health specialists[15,19,20,24,26]; and (6) smoking CD-patients should be advised to quit[17,18,23,26].

The major statements and recommendations included in the guidelines were in line with the recent systematic reviews demonstrating that the role of psychological distress and personality as predisposing factors for the development of IBD remains controversial. Attempts to investigate the role of psychological factors in IBD exhibited rather conflicting results. Among the studies concerning the effects of stress or depression on the course of IBD, the majority suggest that stress worsens IBD, the rest produce either negative or inconclusive results[29]. Eighteen randomized controlled studies (19 papers) were included in a review on psychological therapies in IBD. Psychotherapy was found to have minimal effect on measures of anxiety, depression, quality of life and disease progression although showed promise in reducing pain, fatigue, relapse rate and hospitalisation, and improving medication adherence. It may also be cost effective[30]. Smoking remains the most important environmental factor in IBD. Active smoking increases the risk of developing CD. Moreover, CD patients who start or continue smoking after disease diagnosis are at risk for poorer outcomes such as higher therapeutic requirements and disease-related complications, as compared to those patients who quit smoking or who never smoked[31].

Psychosocial issues are discussed in the majority (10/13) of recently published evidence-based guidelines, supporting their important role in IBD management. There is a need for interdisciplinary evidence-based guidelines in Asia and the United States to provide specific recommendations on the aetiology and management of psychosocial issues in IBD. Patients and mental health specialists should be able to participate in guideline groups to contribute perspectives on psychosocial issues to the guidelines.

There is strong evidence on co-morbidity of IBD with mental disorders which have been shown to impact the disease course. Future guidelines should acknowledge the presence of psychosocial problems in IBD-patients and encourage screening for psychological distress. The best treatment of psychosocial problems of IBD-patients is yet to be determined.

| 1. | Kemp K, Griffiths J, Campbell S, Lovell K. An exploration of the follow-up up needs of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e386-e395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ghosh S, Mitchell R. Impact of inflammatory bowel disease on quality of life: Results of the European Federation of Crohn’s and Ulcerative Colitis Associations (EFCCA) patient survey. J Crohns Colitis. 2007;1:10-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nahon S, Lahmek P, Durance C, Olympie A, Lesgourgues B, Colombel JF, Gendre JP. Risk factors of anxiety and depression in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2086-2091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hisamatsu T, Inoue N, Yajima T, Izumiya M, Ichikawa H, Hibi T. Psychological aspects of inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42 Suppl 17:34-40. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Robertson DA, Ray J, Diamond I, Edwards JG. Personality profile and affective state of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1989;30:623-626. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Moser G, Genser D, Tribl B, Vogelsang H. Psychological stress and disease activity in ulcerative colitis: a multidimensional cross-sectional study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1904. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Miehsler W, Weichselberger M, Offerlbauer-Ernst A, Dejaco C, Reinisch W, Vogelsang H, Machold K, Stamm T, Gangl A, Moser G. Which patients with IBD need psychological interventions? A controlled study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1273-1280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Bennebroek Evertsz’ F, Thijssens NA, Stokkers PC, Grootenhuis MA, Bockting CL, Nieuwkerk PT, Sprangers MA. Do Inflammatory Bowel Disease patients with anxiety and depressive symptoms receive the care they need? J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:68-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Graff LA, Walker JR, Bernstein CN. Depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease: a review of comorbidity and management. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1105-1118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Janke KH, Klump B, Gregor M, Meisner C, Haeuser W. Determinants of life satisfaction in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:272-286. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Nahon S, Lahmek P, Saas C, Durance C, Olympie A, Lesgourgues B, Gendre JP. Socioeconomic and psychological factors associated with nonadherence to treatment in inflammatory bowel disease patients: results of the ISSEO survey. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1270-1276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cámara RJ, Ziegler R, Begré S, Schoepfer AM, von Känel R, Swiss Inflammatory Bowel Disease Cohort Study (SIBDCS) group. The role of psychological stress in inflammatory bowel disease: quality assessment of methods of 18 prospective studies and suggestions for future research. Digestion. 2009;80:129-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. 2011; Available from: http://handbook.cochrane.org. |

| 14. | Deutsches Cochrane-Zentrum, Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften- Institut für Medizinisches Wissensmanagement, Ärztliches Zentrum für Qualität in der Medizin. Manual: Systematic search of literature for guidelines. Version 1.0, May 10, 2013. Available from: http://www.cochrane.de/de/webliographie-litsuche. |

| 15. | National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Ulcerative colitis: management in adults, children and young people. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13301/62378/62378.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2013. |

| 16. | Van Assche G, Dignass A, Bokemeyer B, Danese S, Gionchetti P, Moser G, Beaugerie L, Gomollón F, Häuser W, Herrlinger K. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis part 3: special situations. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:1-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 381] [Cited by in RCA: 344] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Ueno F, Matsui T, Matsumoto T, Matsuoka K, Watanabe M, Hibi T, Guidelines Project Group of the Research Group of Intractable Inflammatory Bowel Disease subsidized by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan and the Guidelines Committee of the Japanese Society of Gastroenterology. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for Crohn's disease, integrated with formal consensus of experts in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:31-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Crohn’s disease: management in adults, children and young people. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13936/61001/61001.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2013. |

| 19. | Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, Ahmad T, Arnott I, Driscoll R, Mitton S, Orchard T, Rutter M, Younge L, Lees C, Ho GT, Satsangi J, Bloom S, IBD Section of the British Society of Gastroenterology. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2011;60:571-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1045] [Cited by in RCA: 966] [Article Influence: 64.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dignass A, Preiss JC, Aust DE, Autschbach F, Ballauff A, Barretton G, Bokemeyer B, Fichtner-Feigl S, Hagel S, Herrlinger KR. [Updated German guideline on diagnosis and treatment of ulcerative colitis, 2011]. Z Gastroenterol. 2011;49:1276-1341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ooi CJ, Fock KM, Makharia GK, Goh KL, Ling KL, Hilmi I, Lim WC, Kelvin T, Gibson PR, Gearry RB, Ouyang Q, Sollano J, Manatsathit S, Rerknimitr R, Wei SC, Leung WK, de Silva HJ, Leong RW, Asia Pacific Association of Gastroenterology Working Group on Inflammatory Bowel Disease. The Asia-Pacific consensus on ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:453-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kornbluth A, Sachar DB, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults: American College Of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:501-523; quiz 524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 899] [Cited by in RCA: 955] [Article Influence: 59.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Dijkstra G, Derijks LJ, Houwert GJ, Wolf H, van Bodegraven AA, CBO-werkgroep ‘IBD bij volwassenen’. [Guideline ‘Diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease in adults’. II. Special situations and organisation of medical care]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2010;154:A1900. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Dignass A, Van Assche G, Lindsay JO, Lémann M, Söderholm J, Colombel JF, Danese S, D’Hoore A, Gassull M, Gomollón F. The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: Current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:28-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1118] [Cited by in RCA: 1041] [Article Influence: 65.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Lichtenstein GR, Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Practice Parameters Committee of American College of Gastroenterology. Management of Crohn's disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:465-483; quiz 464, 484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 619] [Cited by in RCA: 596] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hoffmann JC, Preiss JC, Autschbach F, Buhr HJ, Häuser W, Herrlinger K, Höhne W, Koletzko S, Krieglstein CF, Kruis W. [Clinical practice guideline on diagnosis and treatment of Crohn’s disease]. Z Gastroenterol. 2008;46:1094-1146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Bernstein CN, Singh S, Graff LA, Walker JR, Miller N, Cheang M. A prospective population-based study of triggers of symptomatic flares in IBD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1994-2002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 295] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Langhorst J, Hofstetter A, Wolfe F, Häuser W. Short-term stress, but not mucosal healing nor depression was predictive for the risk of relapse in patients with ulcerative colitis: a prospective 12-month follow-up study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:2380-2386. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Triantafillidis JK, Merikas E, Gikas A. Psychological factors and stress in inflammatory bowel disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;7:225-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | McCombie AM, Mulder RT, Gearry RB. Psychotherapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a review and update. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:935-949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Nos P, Domènech E. Management of Crohn’s disease in smokers: is an alternative approach necessary? World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3567-3574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewers: Lakatos PL, Ohkusa T, Rocha R, Torres MI, Zippi M S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S