Published online Apr 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i13.3649

Revised: November 19, 2013

Accepted: January 2, 2014

Published online: April 7, 2014

Processing time: 261 Days and 0 Hours

AIM: To investigate the prevalence and characteristics of uninvestigated dyspepsia among college students in Zhejiang Province.

METHODS: Young adult students attending undergraduate (within the 4-year program) and graduate (only first-year students) colleges in Zhejiang Province were recruited between November 2010 and March 2011 to participate in the self-report survey study. The questionnaire was designed to collect data regarding demographics (sex and age), general health [weight and height, to calculate body mass index (BMI)], and physical episodes related to gastrointestinal disorders. Diagnosis of dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) was made according to the Rome III criteria. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) was defined by episodes of heartburn and/or acid reflux that occurred at least once a week, according to the Montreal definition.

RESULTS: Of 2520 students recruited for survey participation, only 1870 (males: 967; age range: 17-32 years, mean age: 21.3 years) returned a completed questionnaire. One hundred and eight (5.67%) of the student participants fit the criteria for dyspepsia diagnosis. Stratification analysis of dyspepsia and non-dyspepsia cases showed no statistically significant differences in age or BMI; however, the prevalence of dyspepsia was significantly higher in women than in men (7.53% vs 4.14%, P < 0.05). Stratification analysis of dyspepsia by grade level showed that year 4 undergraduate students had a significantly higher prevalence of dyspepsia (10.00% vs undergraduate year 1: 5.87%, year 2: 3.53% and year 3: 7.24%, and graduate year 1: 3.32%). Nearly all (95.37%) students with dyspepsia reported symptoms of postprandial distress syndrome, but only a small portion (4.63%) reported symptoms suggestive of abdominal pain syndrome. The students with dyspepsia also showed significantly higher rates of IBS (16.67% vs non-dyspepsia students: 6.30%, P < 0.05) and GERD (11.11% vs 0.28%, P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION: Although the prevalence of dyspepsia among Zhejiang college students is low, the significantly higher rates of concomitant IBS and GERD suggest common pathophysiological disturbances.

Core tip: This college-based population survey aimed to determine the prevalence and investigate the characteristics of uninvestigated dyspepsia (UD, according to Rome III criteria) in Zhejiang Province, China. The overall prevalence of UD was relatively low (5.67% in 1870 students), but female sex and senior (year 4) undergraduate status were represented more frequently among the UD cases. In addition, UD cases were more likely to have concomitant irritable bowel syndrome or gastroesophageal reflux disease, suggesting the existence of common etiologies or molecular mechanisms among these gastrointestinal disorders.

- Citation: Li M, Lu B, Chu L, Zhou H, Chen MY. Prevalence and characteristics of dyspepsia among college students in Zhejiang Province. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(13): 3649-3654

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i13/3649.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i13.3649

The gastroduodenal symptoms of dyspepsia are relatively non-specific, and include general abdominal discomfort, early satiety, and bloating. Patients often ignore the condition and not present to clinic until more severe symptoms manifest, such as belching, heartburn, nausea, vomiting, and pain. While untreated dyspepsia is not associated with an increased risk of death, its pathology can put the individual at greater risk of secondary tissue injury, such as mucosal erosion by gastric reflux leading to a chronic inflammation state, or may mask symptoms of other gastrointestinal diseases. Epidemiological surveys have estimated the global prevalence of uninvestigated dyspepsia (UD) to be as low as 7% and as high as 45%[1].

Results from clinical investigations are used to classify the dyspepsia diagnosis as functional dyspepsia (FD) or organic dyspepsia. For both dyspepsia types, some readilymodifiable factors have been identified as potential etiologies, including diet and gastrointestinal infection [mainly Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)]; in addition, clinical management of a co-existing organic disease may help to reduce or eliminate the dyspeptic condition[2]. The lack of an effective targeted therapy, however, means that many patients suffer from chronic dyspepsia and an accompanying detrimental impact on quality of life[3].

Demographic and national factors may play a role in the development and progression of dyspepsia. Epidemiologic studies of dyspepsia in Asian countries have reported incidence rates between 8% and 30%[2], and have suggested that variable symptom profiles of the evaluated subjects and inconsistent diagnostic criteria used by the researchers and healthcare providers may explain this wide range. One survey in Malaysia demonstrated that the economic impact of dyspepsia is greater in urban settings, compared to rural settings[4], in conjunction with the greater disease prevalence in the former. A key differential feature of urban and rural settings is the socio-economic status, which affects nearly every aspect of life from living conditions and diet to working conditions and stress levels. Within Asian urban settings, university students represent a unique population of advanced and productive society members, living in a high stress environment with relatively better access to and understanding of healthcare than their rural counterparts.

Adolescents and young adults, between the ages of 14 and 29 years, account for roughly one-fourth of China’s population and a large portion of city dwellers (State Statistical Bureau of the People’s Republic of China, 2009). The Zhejiang Province, located at the heart of the Yangtze River Delta, is one of the fastest developing urban areas in China and is facing the challenge of establishing a healthcare system adequately equipped and staffed to address the healthcare needs of its expanding population. Considerations for such an endeavor include the particularly high rates of gastric diseases in China, such as gastric cancer and H. pylori infection (although the reported correlation with dyspepsia was relatively weak)[5]; however, the epidemiological characteristics of dyspepsia among urban-dwelling populations of Chinese young adults remain largely unknown. The current study was designed as a self-report survey of college students in the Zhejiang Province to determine the prevalence of UD and investigate its relation to various demographic and physical parameters as well as other common gastrointestinal disorders.

Study recruitment was conducted at two college campuses in the Zhejiang Province between November 2010 and March 2011. Matriculated students in the undergraduate (within the 4-year program) and graduate (only first-year students) programs were included in the study. A total of 2520 students (48% males; mean age: 22.6 ± 3.0 years) were interviewed and offered the survey questionnaire for self-completion. Unreturned or incomplete questionnaires were excluded from the study.

The questionnaire was designed to collect data regarding demographics (sex and age), general health [weight and height, to calculate body mass index (BMI)], and physical episodes related to gastrointestinal disorders. Data related to dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) were chosen according to the ROME III criteria[9]. An individual was classified as having UD if they reported experiencing at least one of the following symptoms during the previous 3 mo, with the first instance occurring at least 6 mo earlier: (1) bothersome postprandial fullness; (2) early satiety; (3) epigastric pain; or (4) epigastric burning. Classification of IBS was made according to report of abdominal pain or discomfort persisting for at least 3 d at least once a month during the previous 3 mo and accompanied by at least two of the following symptoms: (1) relief of pain or discomfort attained after defecation; (2) onset of pain or discomfort associated with a change in stool frequency; or (3) onset of pain or discomfort associated with a change in stool appearance. Data related to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) were chosen according to the Montreal definition for the diagnosis of GERD in population-based studies[10]. Individuals were classified as having GERD if they reported experiencing frequent (at least once weekly) episodes of heartburn or acid regurgitation. For each of the gastrointestinal disorders, the survey questions were translated from the original source into Chinese language by the authors. Any individual classified with two or more of the above disorders was categorized as “GI symptom complex overlap.” Individuals not meeting the criteria for any of the above disorders were categorized as “no functional GI disorder.” Finally, individuals were categorized as having postprandial distress syndrome if they reported bothersome postprandial fullness experienced after an ordinary-sized meal and/or early satiety that prevented from finishing the meal.

Data are expressed as frequency or mean with SD. Normally distributed data were analyzed by the t test, and categorical data were analyzed by the χ2 test. A P value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were carried out with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences v15 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

Of the 2520 students recruited into the study, 315 declined participation and 335 failed to return or returned an incomplete questionnaire. Therefore, the study population consisted of 1870 students in total; the demographic data are summarized in Table 1. The male to female ratio was nearly 1:1. The mean age was 21.3 ± 2.6 years, and the average BMI was 22.28 ± 4.27. Only 5.67% of the total students met the criteria for UD diagnosis. The UD group had a statistically significant predominance of females (P < 0.05) and students in the final year of the 4-year undergraduate program (vs undergraduate years 1, 2 and 3, and graduate year 1, P < 0.05 for all). The mean age and BMI of the UD group were statistically similar to those of the non-UD group.

| UD | Non-UD | Total | P | |

| (n = 108) | (n = 1762) | (n = 1870) | ||

| Sex | < 0.051 | |||

| Male | 40 (4.14) | 927 | 967 | |

| Female | 68 (7.53) | 835 | 903 | |

| Age, yr | 20.96 ± 2.87 | 21.72 ± 1.97 | 21.34 ± 2.56 | |

| BMI | 22.59 ± 3.79 | 21.97 ± 4.76 | 22.28 ± 4.27 | |

| College program and year | < 0.052 | |||

| Undergraduate | ||||

| Year 1 | 16 (5.67) | 266 | 282 | |

| Year 2 | 16 (3.53) | 437 | 453 | |

| Year 3 | 56 (7.24) | 718 | 774 | |

| Year 4 | 12 (10.00) | 108 | 120 | |

| Graduate | ||||

| Year 1 | 8 (3.32) | 233 | 241 | |

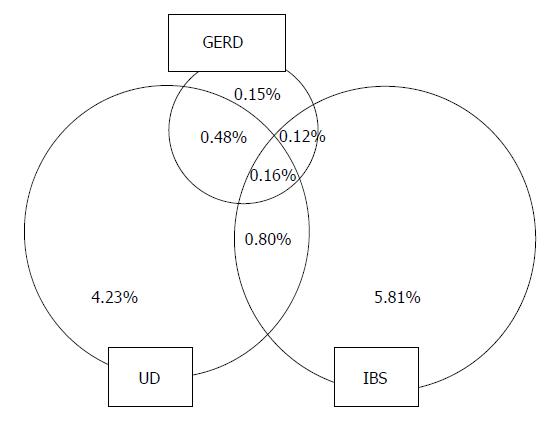

Among the total study population, there were 17 (0.9%) and 129 (6.9%) students who met the criteria for GERD and IBS diagnoses, respectively. Nearly all (95.4%) of the students in the UD group had postprandial distress syndrome. The least frequently reported dyspepsia-related symptoms were intermittent pain or burning localized to the epigastric area (4.6% in the UD group). Twenty-nine of the students had GI symptom complex overlap, with UD + IBS in 18 students (1.0%) and UD + GERD in 12 (0.6%) (Figure 1). The rates of both IBS and GERD were significantly higher in the UD group than in the non-UD group (IBS: 16.7% vs 6.3% and GERD: 11.1% vs 0.3%, P < 0.05 for both). Conversely, the rate of UD was significantly lower in non-IBS students (6.4% vs IBS: 14.0%, P < 0.05) and non-GERD students (0.3% vs GERD: 70.6%, P < 0.05).

Studies of UD prevalence in Asian populations have yielded varied results. Using the Rome I criteria, a study from Hong Kong found a rate of 18.4%[11], while a cross-sectional community study from Singapore that defined UD by the presence of upper abdominal pain found a rate of 7.9%[12]; however, studies from Korea and Malaysia that both used the Rome II criteria found similar rates of UD (approximately 14%)[13,14]. The limited numbers of these studies, though, precludes the ability to definitively conclude if the true rates of UD are associated with national/ethnic differences or the different criteria used to diagnose the condition. Nonetheless, these studies have provided insights into possible etiologic factors of UD in Asians, including age (predominance in older (> 40 years) subjects)[15]. In addition, several Asian studies have evaluated the rate of UD among college students, who represent a unique stress-heavy lifestyle model consisting of long hours of focused physical and cognitive activity under significant social-competitive pressure. As with the studies conducted in the general population, the rates of UD among college students have varied widely by country and study design. A study of college students in Japan found a UD rate of 6.7% using the Rome II criteria[16], while the frequency of dyspepsia found in students from Beijing using Rome III and Anhui using Rome II was 1.6% and 8.3%, respectively[17,18].

The general clinical observation of gastrointestinal symptoms increasing with age has been confirmed by population-based studies[19,20] and associated with diminished sensory responses of the gut tissues[21]. In addition, socioeconomic factors, such as gross domestic product (GDP), have been shown to be inversely associated with dyspepsia[22]. The college students assessed in the current survey resided in an economically developed region; the relatively younger age, higher GDP, and features of the modern urban lifestyle (including high levels of internet connectivity) that characterize college life in Zhejiang Province may contribute to the relatively low rate of dyspepsia detected in our survey (5.8%). In addition, regular smoking was identified as a risk factor of dyspepsia in North Americans (i.e., United States and Canada)[23,24], and regular alcohol intake as a risk factor of UD in Asia-Pacific populations[15,25]. It is possible that the college students surveyed in the current study may have a generally healthier lifestyle, with lower rates of smoking and alcohol consumption than the general population. Another potential explanation for the lower rate detected in the current study, compared to other studies, may be the ROME III diagnostic criteria applied to UD diagnosis[26].

The college students in the current study also showed a predominance of UD in females. In general, functional gastrointestinal disorders have a higher prevalence in women[27], possibly because women are more likely to present for diagnosis and undertake clinical management of such functional disorders, as was shown by a study of IBS and globus hystericus[28]; however, that same study showed no difference in the prevalence of FD between men and women[28]. Studies of individual dyspeptic symptoms have demonstrated sex-related differences in prevalence, as well as in gastric emptying and visceral sensitivity[1,29]. The female-predominant prevalence of UD observed in the current survey may be related to sex-related symptom profiles that were not evaluated in our study. Another key finding of the current study was the significantly higher levels of dyspeptic symptoms in senior level undergraduates (in year 4 of the program); it is possible that this result was related to an increased stressful environment, as these students are facing a rapidly approaching significant lifestyle change (from college matriculation to employment).

Dyspepsia, GERD, and IBS are common gastrointestinal conditions both in China and worldwide. The different prevalence rates of these three disorders observed in the current population of college students may also reflect the different strengths of associations with stress-related factors. For example, a study of the relation between psychological disorders and IBS, FD and non-erosive reflux disorder showed that anxiety was significantly more common in patients with IBS[30]. College students are at a higher risk of psychological disorders, such as anxiety[31]. However, the current study population showed a remarkably lower prevalence of GERD (< 1%) compared to the most recent worldwide estimates, which range between 10% and 20%[10]. The lower rate may be associated with the particularly younger age of the current study population and/or the lower BMI[22]. The rate of dyspepsia overlapping with GERD was higher, and closer to that previously reported from a Japanese cohort of college students[16].

Several case reports of dyspepsia, IBS and GERD overlap exist[32-34]. In the same Japanese cohort, the prevalence of dyspepsia + IBS was significantly higher than that of dyspepsia + GERD[16], which was similar to the findings in the current study of Chinese college students (1.0% and 0.6%, respectively). Collected data in the literature suggest that GERD is a common occurrence in dyspepsia, with rates of 22% to 50% being reported[35-38]. Similarly, some studies have suggested that the occurrence of IBS in dyspeptic patients is not uncommon; the current study population showed a rate of dyspepsia + IBS that fell within the range of prevalence rates previously reported for Asian populations[16,39-40]. While the precise mechanisms underlying such overlap in gastrointestinal disorders remain unknown, it is likely that pathophysiological factors shared between the three, such as altered motility, visceral hypersensitivity, brain-gut dysfunction or psychological distress, play key roles[41-44]. In addition, the significant overlap of symptoms among dyspepsia, IBS and GERD raises the question of whether the functional gastrointestinal disorders actually represent multiple separate disorders or a single clinical entity.

Though dyspepsia is not fatal, it is associated with substantial impairment of quality of life and poses a significant burden on society, with sufferers experiencing higher rates of work absenteeism, reduced productivity, and higher reliance on healthcare resources than the general population[45,46]. For college students, the symptoms associated with dyspepsia may have a marked impact on the individual’s study habits, ability to concentrate or attend classes, and performance on tests. To the best of our knowledge, no Chinese universities currently have a student outreach program to enhance their students’ knowledge of digestive health; by providing campus-wide health lectures, which would include symptoms and management of common stress-related psychological and physical disorders, the rates of gastrointestinal disorders, such as dyspepsia, may be reduced.

Although this investigation provides new insights into the prevalence and characteristics of UD in Chinese college students, it relied solely on data gathered from a self-report questionnaire; thus, the physical- and disease-related data may have been underreported or exaggerated. In addition, the questionnaire was newly developed according to the objectives of the current study. Since the questionnaire has not been validated, its test-retest reliability and validity are unknown. Moreover, the focus of questions to determine specific symptoms of dyspepsia, GERD and IBS precludes the ability of this study to analyze organic gastrointestinal diseases.

In conclusion, the prevalence of UD in college students from the Zhejiang Province was low (5.7%), possibly due to the young age and low BMI of this population[47]. The UD rates were highest in students who were female and in the senior year of a 4-year undergraduate program. Nearly all of the students who fit the criteria for UD diagnosis also reported symptoms suggestive of postprandial distress syndrome and there was a remarkable portion of dyspepsia cases with concomitant IBS or GERD, suggesting the existence of common etiologies or molecular mechanisms among these gastrointestinal disorders.

Epidemiological studies suggest that uninvestigated dyspepsia (UD) is a common gastrointestinal disorder worldwide. However, there is little data on the prevalence of UD and its overlap with other gastrointestinal diseases in China, particularly among college students who represent a unique population of young adults living in urban settings under particularly high stress conditions.

Using a questionnaire with validated Chinese language Rome III diagnostic criteria included, this study surveyed undergraduate (4-year program) and graduate (in year 1) students residing in the Zhejiang Province to determine prevalence and characteristics of UD.

According to Rome III criteria, the prevalence of UD in college students from the Zhejiang Province was 5.7%. The symptoms of dyspepsia were most frequently reported by females and senior level (year 4) undergraduate students, suggesting sex- and/or stress-related components. There was a remarkable portion of dyspepsia cases with concomitant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), suggesting the existence of common etiologies or molecular mechanisms among these gastrointestinal disorders.

While the reasons for the relatively low prevalence rate of UD among college students from the Zhejiang Province remain to be fully elucidated, the data indicate that this condition is not infrequent among this population and deserves attention to promote both diagnosis and clinical management that may prevent potential damage caused by a chronic condition.

This is a cross-sectional survey of 2520 Chinese college students in the Zhejiang Province of China that examined the prevalence and characteristics of UD, including overlap with IBS and GERD. This study provides novel insights into the current epidemiologic state of UD in this population that represents a group of individuals living a modern urban lifestyle and under significant stress.

| 1. | Mahadeva S, Goh KL. Epidemiology of functional dyspepsia: a global perspective. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2661-2666. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Ghoshal UC, Singh R, Chang FY, Hou X, Wong BC, Kachintorn U. Epidemiology of uninvestigated and functional dyspepsia in Asia: facts and fiction. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17:235-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | El-Serag HB, Talley NJ. Health-related quality of life in functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:387-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mahadeva S, Yadav H, Everett SM, Goh KL. Economic impact of dyspepsia in rural and urban malaysia: a population-based study. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;18:43-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Shi R, Xu S, Zhang H, Ding Y, Sun G, Huang X, Chen X, Li X, Yan Z, Zhang G. Prevalence and risk factors for Helicobacter pylori infection in Chinese populations. Helicobacter. 2008;13:157-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lin JT, Wang JT, Wang TH, Wu MS, Lee TK, Chen CJ. Helicobacter pylori infection in a randomly selected population, healthy volunteers, and patients with gastric ulcer and gastric adenocarcinoma. A seroprevalence study in Taiwan. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993;28:1067-1072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lin DB, Nieh WT, Wang HM, Hsiao MW, Ling UP, Changlai SP, Ho MS, You SL, Chen CJ. Seroepidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection among preschool children in Taiwan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:554-558. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Wang LY, Lin JT, Cheng YW, Chou SJ, Chen CJ. Seroepidemiology of Helicobacter pylori among adolescents in Taiwan. Zhonghua Minguo Weisheng Wuji Mianyixue Zazhi. 1996;29:10-17. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Drossman DA. The functional gastrointestinal disorders and the Rome III process. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1377-1390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1467] [Cited by in RCA: 1493] [Article Influence: 74.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-1920; quiz 1943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2368] [Cited by in RCA: 2518] [Article Influence: 125.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Hu WH, Wong WM, Lam CL, Lam KF, Hui WM, Lai KC, Xia HX, Lam SK, Wong BC. Anxiety but not depression determines health care-seeking behaviour in Chinese patients with dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome: a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:2081-2088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ho KY, Kang JY, Seow A. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in a multiracial Asian population, with particular reference to reflux-type symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1816-1822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jeong JJ, Choi MG, Cho YS, Lee SG, Oh JH, Park JM, Cho YK, Lee IS, Kim SW, Han SW. Chronic gastrointestinal symptoms and quality of life in the Korean population. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6388-6394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mahadeva S, Yadav H, Rampal S, Goh KL. Risk factors associated with dyspepsia in a rural Asian population and its impact on quality of life. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:904-912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shah SS, Bhatia SJ, Mistry FP. Epidemiology of dyspepsia in the general population in Mumbai. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2001;20:103-106. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Hori K, Matsumoto T, Miwa H. Analysis of the gastrointestinal symptoms of uninvestigated dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome. Gut Liver. 2009;3:192-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hu J, Yang YS, Peng LH, Sun G, Guo X, Wang WF. Investigation of the risk factors of FD in Beijing university students. Disan Junyi Daxue Xuebao. 2009;31:1498-1501. |

| 18. | Wang QM, Wu ZX, Yin BS, Zheng BH, Zhang KG, Ding XP, Zhang ML. Epidemiological survey of functional dyspepsia among students of college in Hefei. Zhongguo Linchuang Baojian Zazhi. 2005;8:205-207. |

| 19. | Nocon M, Keil T, Willich SN. Prevalence and sociodemographics of reflux symptoms in Germany--results from a national survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1601-1605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ruigómez A, García Rodríguez LA, Wallander MA, Johansson S, Graffner H, Dent J. Natural history of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease diagnosed in general practice. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:751-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Gururatsakul M, Holloway RH, Adam B, Liebregts T, Talley NJ, Holtmann GJ. The ageing gut: diminished symptom response to a standardized nutrient stimulus. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:246-e77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Haag S, Andrews JM, Gapasin J, Gerken G, Keller A, Holtmann GJ. A 13-nation population survey of upper gastrointestinal symptoms: prevalence of symptoms and socioeconomic factors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:722-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Shaib Y, El-Serag HB. The prevalence and risk factors of functional dyspepsia in a multiethnic population in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2210-2216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tougas G, Chen Y, Hwang P, Liu MM, Eggleston A. Prevalence and impact of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in the Canadian population: findings from the DIGEST study. Domestic/International Gastroenterology Surveillance Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2845-2854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Haque M, Wyeth JW, Stace NH, Talley NJ, Green R. Prevalence, severity and associated features of gastro-oesophageal reflux and dyspepsia: a population-based study. N Z Med J. 2000;113:178-181. [PubMed] |

| 26. | van Kerkhoven LA, Laheij RJ, Meineche-Schmidt V, Veldhuyzen-van Zanten SJ, de Wit NJ, Jansen JB. Functional dyspepsia: not all roads seem to lead to rome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:118-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lydiard RB. Increased prevalence of functional gastrointestinal disorders in panic disorder: clinical and theoretical implications. CNS Spectr. 2005;10:899-908. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, Temple RD, Talley NJ, Thompson WG, Whitehead WE, Janssens J, Funch-Jensen P, Corazziari E. U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1569-1580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1502] [Cited by in RCA: 1434] [Article Influence: 43.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 29. | Talley NJ, Verlinden M, Jones M. Can symptoms discriminate among those with delayed or normal gastric emptying in dysmotility-like dyspepsia? Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1422-1428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hartono JL, Mahadeva S, Goh KL. Anxiety and depression in various functional gastrointestinal disorders: do differences exist? J Dig Dis. 2012;13:252-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Axelson DA, Birmaher B. Relation between anxiety and depressive disorders in childhood and adolescence. Depress Anxiety. 2001;14:67-78. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 32. | Jung HK, Halder S, McNally M, Locke GR, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ. Overlap of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and irritable bowel syndrome: prevalence and risk factors in the general population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:453-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Lee SY, Lee KJ, Kim SJ, Cho SW. Prevalence and risk factors for overlaps between gastroesophageal reflux disease, dyspepsia, and irritable bowel syndrome: a population-based study. Digestion. 2009;79:196-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kaji M, Fujiwara Y, Shiba M, Kohata Y, Yamagami H, Tanigawa T, Watanabe K, Watanabe T, Tominaga K, Arakawa T. Prevalence of overlaps between GERD, FD and IBS and impact on health-related quality of life. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1151-1156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 35. | Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ. Onset and disappearance of gastrointestinal symptoms and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:165-177. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Talley NJ, Piper DW. The association between non-ulcer dyspepsia and other gastrointestinal disorders. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1985;20:896-900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Agréus L, Svärdsudd K, Nyrén O, Tibblin G. Irritable bowel syndrome and dyspepsia in the general population: overlap and lack of stability over time. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:671-680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 459] [Cited by in RCA: 451] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Crean GP, Holden RJ, Knill-Jones RP, Beattie AD, James WB, Marjoribanks FM, Spiegelhalter DJ. A database on dyspepsia. Gut. 1994;35:191-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Ghoshal UC, Abraham P, Bhatt C, Choudhuri G, Bhatia SJ, Shenoy KT, Banka NH, Bose K, Bohidar NP, Chakravartty K. Epidemiological and clinical profile of irritable bowel syndrome in India: report of the Indian Society of Gastroenterology Task Force. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2008;27:22-28. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Okumura T, Tanno S, Ohhira M, Tanno S. Prevalence of functional dyspepsia in an outpatient clinic with primary care physicians in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:187-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Abrahamsson H. Gastrointestinal motility in patients with the irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1987;130:21-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Corsetti M, Caenepeel P, Fischler B, Janssens J, Tack J. Impact of coexisting irritable bowel syndrome on symptoms and pathophysiological mechanisms in functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1152-1159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Iovino P, Azpiroz F, Domingo E, Malagelada JR. The sympathetic nervous system modulates perception and reflex responses to gut distention in humans. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:680-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Kennedy TM, Jones RH, Hungin AP, O’flanagan H, Kelly P. Irritable bowel syndrome, gastro-oesophageal reflux, and bronchial hyper-responsiveness in the general population. Gut. 1998;43:770-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Lu CL, Lang HC, Chang FY, Chen CY, Luo JC, Wang SS, Lee SD. Prevalence and health/social impacts of functional dyspepsia in Taiwan: a study based on the Rome criteria questionnaire survey assisted by endoscopic exclusion among a physical check-up population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:402-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 46. | Moayyedi P, Mason J. Clinical and economic consequences of dyspepsia in the community. Gut. 2002;50 Suppl 4:iv10-iv12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Richter JE. Dyspepsia: organic causes and differential characteristics from functional dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1991;182:11-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewers: Dang SS, Mahadeva S, Qin JM S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Liu XM