Published online Feb 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i7.1098

Revised: September 4, 2012

Accepted: October 16, 2012

Published online: February 21, 2013

AIM: To study current treatment options for pediatric hepatitis C infection and their associated success rates.

METHODS: We retrospectively reviewed charts of thirty children who had been treated with combination therapy of pegylated interferon alfa plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C infection. Patients had been treated with ribavirin (15 mg/kg per day) and either pegylated interferon alfa 2a (180 mg/m2 once weekly) or pegylated interferon alfa 2b (1.5 mg/kg once weekly). Patients’ follow-up included subjective assessment of complaints, physical examination including weight and height, as well as laboratory evaluations for viral load [before treatment, at 12 wk, and 6 mo following treatment completion, as determined by sustained viral response (SVR)], complete blood count, liver enzymes, alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, renal function tests, and thyroid function tests. For patients not achieving a two log decrease in viral load at treatment week 12, treatment was discontinued and the patient was considered a treatment non-responder.

RESULTS: Thirty children aged 3-18 years were included in the study. Twenty patients (11 males, 9 females) received pegylated interferon alfa 2b and ten patients (6 males, 4 females) received pegylated interferon alfa 2a. Twenty-three patients were infected with genotype 1, six patients were infected with genotype 3, and one patient was infected with genotype 2. Twenty patients (67%) achieved SVR. Treatment success rates were 90% with pegylated interferon alfa 2a vs 55% with pegylated interferon alfa 2b. Although a trend was noted for improved outcomes in the group receiving pegylated interferon alfa 2a, there were no statistically significant outcome differences between the two treatment groups (P = 0.1). Treatment success was 56.5% for patients infected with genotype 1 virus, compared to 100% for patients infected with other genotypes (P = 0.064). There was no difference in treatment response between males and females. A cut-off age of twelve years was used to dichotomize younger vs older participants; however, no difference in treatment response was observed between these groups. Using multivariate regression analysis, we could not determine predictors for achieving SVR from among the variables we examined (age, sex, and viral genotype). Although we noted a trend toward SVR with peginterferon alfa-2a, there was no statistical difference between the two peginterferons. A high incidence of adverse reactions to treatment was noted. Twenty-five patients (83%) suffered from at least one adverse reaction, but most experienced more than one adverse reaction. All patients except one became leukopenic (white blood cell count less than 5500 leukocytes/μL), six (20%) became anemic (hemoglobin less than 110 g/L), and one (3.3%) became thrombocytopenic (platelets less than 100 000/μL).

CONCLUSION: Combination therapy to treat hepatitis C in children is as effective as in adults. There may be a benefit for treatment with pegylated interferon alfa 2a.

- Citation: Rosen I, Kori M, Adiv OE, Yerushalmi B, Zion N, Shaoul R. Pegylated interferon alfa and ribavirin for children with chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(7): 1098-1103

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i7/1098.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i7.1098

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is relatively uncommon in the pediatric population. Populations at risk of HCV infection are infants born to infected mothers who acquire the infection vertically, and children with chronic diseases who acquire the virus through infected blood products[1]. Vertical transmission is the predominant source for new pediatric HCV infections. Estimated transmission rates are 2%-5% when the mother is viremic during pregnancy[1,2]. Mothers with greater than 106 copies/mL of HCV RNA are more likely to transmit the infection to their infants compared to mothers with lower levels of viremia. Chronic hepatitis C (CHC) develops in 55%-80% of infected children[2,3]. The prevalence of HCV in children in developed countries ranges from 0.1% to 0.4%[4-6]. Treatment is contraindicated for patients less than three years of age because of safety concerns and to allow for spontaneous viral clearance. After age four, spontaneous viral clearance is unlikely[7]. The rate of viral clearance in children with CHC who acquired the infection vertically is 20%[8]. Most children who clear the virus do so during the first five years of follow-up.

In most cases, HCV infection in children is asymptomatic. Histological findings are minor and severe complications are uncommon. However, chronic hepatic inflammation from HCV infection can progress to advanced liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in four percent to six percent of infected children[9,10]. The risk of developing cirrhosis is approximately 20% and the risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma is 2%-5%[11]. Hepatocellular carcinoma has been reported in adolescents with CHC[12].

The current treatment of choice for CHC in children, as in the adult population[13,14], is combination pegylated interferon alfa plus ribavirin. We have been prescribing this treatment regimen for the last seven years. We retrospectively reviewed charts of patients who had been treated for CHC with pegylated interferon alfa plus ribavirin in several Israeli Pediatric Gastroenterology Centers.

Complete data were available for a total of thirty children with chronic HCV infection who were treated between 2003 and 2010. Chronic HCV infection was diagnosed by the presence of anti-HCV antibodies and HCV RNA positivity. Additional available information included: alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels during the three mo prior to treatment, laboratory studies during follow-up, and, for some patients, liver biopsy specimens showing evidence of CHC or Actitest and Fibrotest results.

Ten patients were treated with pegylated interferon alfa 2a (180 mg/m2 once weekly) plus ribavirin 15 mg/kg per day and 20 patients were treated with pegylated interferon alfa 2b (1.5 mg/kg once weekly) plus ribavirin (15 mg/kg per day). The decision for which peginterferon was prescribed depended on the patient’s medical insurance. Length of treatment was 24 wk for patients with genotypes 2 or 3 (seven patients) and 48 wk for patients with genotype 1 (twenty-three patients). Patient follow-up included assessment of subjective complaints, physical examination with weight and height, and laboratory workup which included viral load [before treatment, at 12 wk, and 6 mo following treatment completion, as determined by sustained viral response (SVR)], complete blood count, liver enzymes, alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, renal function tests, and thyroid function tests. In patients not achieving a two log10 IU/mL decrease in their viral loads at week 12, treatment was discontinued and the patient was considered a treatment non-responder.

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software package version 15 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States).The normality of quantitative variables was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Because most of the quantitative variables were not normally distributed, the Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyze differences between SVR groups. Fisher’s exact test was used to determine the relationship between SVR groups and categorical variables (gender, treatment type, genotype). Logistic regression was performed to predict relationships between SVR groups and several independent variables. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Thirty patients (13 girls and 17 boys) aged three to eighteen years were included in this study. Patients’ characteristics and results are shown in Table 1. Twelve acquired HCV vertically, eleven through blood products, one by needle stick, and six patients had no identifiable source of infection.

| Non-responders (n = 10) | Gained SVR (n = 20) | P value | |

| Male | 6 (60) | 11 (55) | 1.00 |

| Age ≥ 12 yr | 7 (70) | 14 (70) | 1.00 |

| Peginterferon alfa-2a treatment | 1 (10) | 9 (45) | 0.1 |

| Genotype 1 | 10 (100) | 13 (65) | 0.065 |

| WBC (cells/μL)1 | 3422.22 ± 839.47 | 3296.500 ± 834.57 | 0.39 |

| HGB (g/L)1 | 110.99 ± 9.1 | 110.26 ± 10 | 0.07 |

| ALT (U/L)1 | 52.33 ± 16.42 | 77.85 ± 41.98 | 0.08 |

| AST (U/L)1 | 43.90 ± 19.31 | 55.65 ± 31.39 | 0.54 |

| Weight (kg)1 | 48.66 ± 23.76 | 51.62 ± 21.96 | 0.66 |

| Median viral load | 747 000 | 332 500 | 0.49 |

It should be noted that several patients had underlying comorbidities: one patient had Becker Muscular Dystrophy, one patient had proctitis, one had Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia, one had human immunodeficiency virus infection, and one had Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Twenty-three patients were infected with HCV genotype 1 (genotype 1b in twenty patients and genotype 1a in three patients). Six patients had genotype 3a, and one patient had genotype 2. Viral loads prior to treatment ranged from 134 000 to 26 200 000 copies/mL. ALT levels prior to treatment ranged from 24 to 183 U/L (mean 69.93 ± 37.64 U/L).

Liver histology ranged from mild chronic portal inflammation to moderate portal inflammation with fibrous expansion. Fibrotest scores ranged from 0 to 3 and activity ranged from 0 to 3 on the Actitest. Twenty-six patients were interferon-naïve, three patients were non-responders to previous interferon monotherapy, and one patient was a non-responder to previous pegylated interferon alfa 2a therapy (and had also been treated with pegylated interferon alfa 2b).

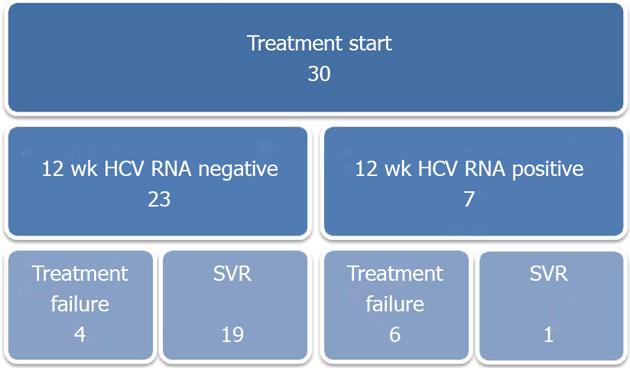

Viral load at 12 wk was undetectable in twenty-two patients, slightly positive in one patient, and positive in six patients. For one patient, viral load examination was delayed and was not tested until six months after treatment initiation, at which time it was negative (Figure 1). SVR six months following treatment completion was achieved in twenty patients, for an overall treatment success rate of 67%.

Among twenty-three patients with undetectable HCV RNA [as measured by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)] following 12 wk of treatment, 19 achieved SVR. Only one of seven patients who were positive for HCV RNA at 12 wk achieved SVR. This patient’s viral load had decreased greater than two log10 IU/mL at 12 wk compared to baseline (Figure 1).

Forty-three percent (10/23) of those with genotype 1 did not achieve SVR; of those, four responded to treatment after twelve weeks, and six were non-responders. One patient who failed to respond was non-compliant with ribavirin, and another patient stopped ribavirin due to serious headaches and rash.

Twenty patients (eleven males, nine females) received pegylated interferon alfa 2b and ten patients (six males, four females) received pegylated interferon alfa 2a. The success rate was 90% (9/10) for those receiving pegylated interferon 2a combined with ribavirin (six patients with genotype 1b, three with genotype 1a, and one with genotype 3a). The success rate for those with genotype 1b was 83% (5/6).

Fifty-five percent (11/20) of patients receiving pegylated interferon alfa 2b and ribavirin treatment (fourteen patients with genotype 1b, five patients with genotype 3a, and one patient with genotype 2) achieved SVR. Only 36% (5/14) of patients with genotype 1b achieved SVR with this treatment. Although a trend was noted in favor of pegylated interferon alfa 2a, there were no significant differences between the two treatment groups (P = 0.1). The treatment success rate was 56.5% in patients infected with genotype 1 virus, compared to 100% in patients infected with non-1 genotypes (P = 0.064).

There was no statistical difference in response to treatment between males and females. A cut-off age of twelve years was used to compare response to treatment between younger and older patients; no statistical difference was observed. Treatment failure occurred only among those infected with genotype 1 HCV.

We could not determine predictors for achieving SVR from among the variables examined (age, sex, and viral genotype) in our multivariate regression analysis. We did observe a trend toward greater SVR when using peginterferon alfa-2a, but this difference between the two peginterferons was not statistically significant, most likely due to our small sample.

Adverse events were common, occurring in 83% of patients (25/30) and including flu-like symptoms, malaise, headaches, fever, lymphadenopathy, anorexia, weight loss, hair loss, myalgia, fat necrosis, somnolence, sleep disturbance, anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, oral aphthae and aseptic meningitis (following treatment completion). No patient experienced severe bone marrow suppression (Table 2).

| Adverse reaction | Peginterferon-alfa 2a (n = 10) | Peginterferon-alfa 2b (n = 20) | Total |

| None | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Flu-like symptoms | 4 | 5 | 9 |

| Weight loss | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Hair loss | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Headache | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Aseptic meningitis | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| GI symptoms | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| Oral aphthae | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Pruritus | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Fat necrosis | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Sleep disturbance | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Absolute neutropenia | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Anemia (HGB < 110 g/L) | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Thrombocytopenia (platelets < 100 000 cells/μL) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Direct hyperbilirubinemia (mg/dL) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Indirect hyperbilirubinemia (mg/dL) | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Leukocyte counts before treatment ranged from 3630 to 11400 cells/μL (mean ± SD, 7540.69 ± 1950.3 cells/μL) and from 1750 to 5770 cells/μL (mean ± SD, 3335.5 ± 823 cells/μL) during treatment. The Mann-Whitney U test showed a significant difference between leukocyte levels before and during treatment (P < 0.001). Hemoglobin levels also decreased, from 116 to 169 g/L (mean ± SD, 135.3 ± 12.8 g/L) before treatment to 95 to 139 g/L (mean ± SD, 115 ± 10.2 g/L) during treatment, as determined by t-test (P < 0.001).

Only one patient experienced direct hyperbilirubinemia of 15 mg/L, with a total bilirubin level of 18 mg/L. Another patient had indirect hyperbilirubinemia of 26 mg/L during treatment. All patients had normal gamma-glutamyl transferase levels and renal function throughout treatment. One patient developed hypothyroidism which subsequently resolved.

Combination therapy of pegylated interferon alfa plus ribavirin for chronic HCV infection in children was found to be as effective as in adults. Fifty-seven percent of children infected with genotype 1 achieved SVR and children infected with other HCV genotypes achieved 100% SVR. The success rates are similar to success rates reported in other pediatric studies[13,15].

Treatment strategies for CHC have evolved over the years, from interferon monotherapy to combination interferon alfa plus ribavirin[16] to combination pegylated interferon alfa plus ribavirin[14,15,17,18]. This latter combination is currently the treatment of choice for CHC in children, as in adults[13,14]. Schwarz et al[15] reported that combination ribavirin plus peginterferon alfa is superior to peginterferon alfa and placebo for children and adolescents with CHC. Two options exist for pegylated interferon alfa therapy: pegylated interferon alfa 2a and pegylated interferon alfa 2b[19-23]. The main treatment goal is to achieve an SVR, defined as undetectable serum HCV RNA for six months following cessation of treatment. Treatment outcomes depend on HCV genotype and viral load at the beginning of treatment[13,17,24]. The genotype is a key predictor of treatment response[24]. Wirth et al[14] found that patients infected with genotype 1 experienced 53% SVR, compared to patients with genotypes 2 or 3 who had 93% SVR, and patients with genotype 4 who had 80% SVR. Baseline viral load is the main response predictor for patients infected with HCV genotype 1. SVR may be more likely in patients who have lower viral loads[14]. In a systematic review, Hu et al[13] reported that SVR rates in children with CHC ranged from 30% to 100%, comparable to those seen among adults.

Combination treatment causes high rates of adverse reactions, with almost all children suffering from transient flu-like symptoms. Other adverse reactions are diverse. In our study, 83% of patients suffered from adverse reactions, but almost all patients remained compliant with therapy. Indeed, in most studies, the treatment is tolerated and compliance is good[24,25]. The treatment protocol has been associated with significant changes in body weight, linear growth and body composition (loss of fat mass); however, these effects seem reversible[26].

In adults, HCV RNA PCR results after twelve weeks of treatment predict treatment outcomes. Failure to respond (a less than two log10 drop from baseline HCV RNA levels) is associated with non-response to treatment, and the therapy should be discontinued. It is unknown whether this rule applies to pediatric patients as well[13]. However, this rule does fit with our current findings.

All treatment failures in our study occurred in patients infected with genotype 1, which was also the most frequent genotype among our patients. SVR rates depend on genotype, as in the adult population, and success rates are significantly better (greater than 90%) in patients infected with genotypes 2 and 3 compared to patients infected with genotype 1 or 4 (approximately 50%)[14].

Although both pegylated interferon alfa regimens have similar safety profiles, success rates differ. In a systematic review of twelve randomized clinical trials including 5008 patients, Awad et al[20] concluded that peginterferon alfa-2a is associated with higher SVR than peginterferon alfa-2b. We have also noted different success rates between the two pegylated interferon alfa products, as reported in previous studies[19,20,22,23]. With caution and consideration of our small sample size, our results show the trend by which combination treatment with pegylated interferon alfa 2a may be superior to pegylated interferon alfa 2b. Such a trend has been shown previously only in adult studies[19,20,22].

The main weakness of the study is its retrospective nature and relatively small number of patients. Nevertheless, our results are consistent with previous studies in children and adults and our study is the first to compare the two pegylated interferon products in children. Further prospective studies are highly encouraged.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a virus that chronically infects the liver. Infection by this virus is a known risk factor for liver disease, liver failure and its complications, and even cases of liver tumors (hepatocellular carcinoma). There are limited publications about experience in treating children, recommendations for a preferred regimen, and data on treatment success rates. In this study, thirty children with chronic hepatitis C had been treated with combination therapy of peginterferon alfa plus ribavirin (as is recommended in adults). Ten of them had been given peginterferon alfa 2a, twenty of them had been given peginterferon alfa 2b, since there is no accepted preference of either of these drugs.

This paper introduces the Israeli experience in treatment of children with chronic HCV infection, including success rates and adverse reactions.

The study found that success rates in children are very similar to those reported in adults. Although no significant superiority of either of the drugs was found, (most probably due to small group size), a trend for better results was noted with peginterferon alfa 2a. Even though side effects were very common during the treatment regimen, children were found to be very compliant, and most of them completed the treatment course.

The study results suggest that success rates of treatment are similar to those noted in adults, and that treatment with combination peginterferon alfa 2a plus ribavirin may be superior.

Peginterferon alfa: A pegylated interferon drug that is given in a subcutaneous manner once a week, as opposed to previous treatment with interferon, which was given by injections 3 times a week. Treatment success: Achieving sustained viral response means that six months after treatment completion there is no detectable HCV RNA in the blood.

Data on HCV therapy in pediatric patients are limited, thus this paper adds important information.

| 1. | Guido M, Rugge M, Jara P, Hierro L, Giacchino R, Larrauri J, Zancan L, Leandro G, Marino CE, Balli F. Chronic hepatitis C in children: the pathological and clinical spectrum. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1525-1529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chang MH, Ni YH, Hwang LH, Lin KH, Lin HH, Chen PJ, Lee CY, Chen DS. Long term clinical and virologic outcome of primary hepatitis C virus infection in children: a prospective study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:769-773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Vogt M, Lang T, Frösner G, Klingler C, Sendl AF, Zeller A, Wiebecke B, Langer B, Meisner H, Hess J. Prevalence and clinical outcome of hepatitis C infection in children who underwent cardiac surgery before the implementation of blood-donor screening. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:866-870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 358] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Hepatitis C virus infection. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Infectious Diseases. Pediatrics. 1998;101:481-485. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Ades AE, Parker S, Walker J, Cubitt WD, Jones R. HCV prevalence in pregnant women in the UK. Epidemiol Infect. 2000;125:399-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gerner P, Wirth S, Wintermeyer P, Walz A, Jenke A. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in children admitted to an urban hospital. J Infect. 2006;52:305-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bortolotti F, Verucchi G, Cammà C, Cabibbo G, Zancan L, Indolfi G, Giacchino R, Marcellini M, Marazzi MG, Barbera C. Long-term course of chronic hepatitis C in children: from viral clearance to end-stage liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1900-1907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | European Paediatric Hepatitis C Virus Network. Three broad modalities in the natural history of vertically acquired hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:45-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Goodman ZD, Makhlouf HR, Liu L, Balistreri W, Gonzalez-Peralta RP, Haber B, Jonas MM, Mohan P, Molleston JP, Murray KF. Pathology of chronic hepatitis C in children: liver biopsy findings in the Peds-C Trial. Hepatology. 2008;47:836-843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Guido M, Bortolotti F, Leandro G, Jara P, Hierro L, Larrauri J, Barbera C, Giacchino R, Zancan L, Balli F. Fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C acquired in infancy: is it only a matter of time? Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:660-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Freeman AJ, Dore GJ, Law MG, Thorpe M, Von Overbeck J, Lloyd AR, Marinos G, Kaldor JM. Estimating progression to cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2001;34:809-816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 440] [Cited by in RCA: 425] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | González-Peralta RP, Langham MR, Andres JM, Mohan P, Colombani PM, Alford MK, Schwarz KB. Hepatocellular carcinoma in 2 young adolescents with chronic hepatitis C. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:630-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hu J, Doucette K, Hartling L, Tjosvold L, Robinson J. Treatment of hepatitis C in children: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wirth S, Ribes-Koninckx C, Calzado MA, Bortolotti F, Zancan L, Jara P, Shelton M, Kerkar N, Galoppo M, Pedreira A. High sustained virologic response rates in children with chronic hepatitis C receiving peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin. J Hepatol. 2010;52:501-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Schwarz KB, Gonzalez-Peralta RP, Murray KF, Molleston JP, Haber BA, Jonas MM, Rosenthal P, Mohan P, Balistreri WF, Narkewicz MR. The combination of ribavirin and peginterferon is superior to peginterferon and placebo for children and adolescents with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:450-458.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wirth S, Lang T, Gehring S, Gerner P. Recombinant alfa-interferon plus ribavirin therapy in children and adolescents with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36:1280-1284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 17. | Davison SM, Kelly DA. Management strategies for hepatitis C virus infection in children. Paediatr Drugs. 2008;10:357-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Palumbo E. Treatment for chronic hepatitis C in children: a review. Am J Ther. 2009;16:446-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ascione A, De Luca M, Tartaglione MT, Lampasi F, Di Costanzo GG, Lanza AG, Picciotto FP, Marino-Marsilia G, Fontanella L, Leandro G. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin is more effective than peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for treating chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:116-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Awad T, Thorlund K, Hauser G, Stimac D, Mabrouk M, Gluud C. Peginterferon alpha-2a is associated with higher sustained virological response than peginterferon alfa-2b in chronic hepatitis C: systematic review of randomized trials. Hepatology. 2010;51:1176-1184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Jansen PL, Reesink HW. Antiviral effect of peginterferon alfa-2b and alfa-2a compared. J Hepatol. 2006;45:172-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rumi MG, Aghemo A, Prati GM, D’Ambrosio R, Donato MF, Soffredini R, Del Ninno E, Russo A, Colombo M. Randomized study of peginterferon-alpha2a plus ribavirin vs peginterferon-alpha2b plus ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:108-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zeuzem S. Do differences in pegylation of interferon alfa matter? Gastroenterology. 2010;138:34-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wirth S, Kelly D, Sokal E, Socha P, Mieli-Vergani G, Dhawan A, Lacaille F, Saint Raymond A, Olivier S, Taminiau J. Guidance for clinical trials for children and adolescents with chronic hepatitis C. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:233-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wirth S, Pieper-Boustani H, Lang T, Ballauff A, Kullmer U, Gerner P, Wintermeyer P, Jenke A. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin treatment in children and adolescents with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2005;41:1013-1018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Jonas MM, Balistreri WF, Gonzalez-Peralta RP, Haber B, Mohan P, Molleston JP, Murray KF, Narkewicz M, Rosenthal P, Schwarz KB. Changes in body mass index and body composition in children treated with peginterferon for chronic hepatitis C in the PEDS-C trial. Hepatology. 2009;50:636a-637a. |

P- Reviewer Tacke F S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L