Published online Feb 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i6.874

Revised: October 3, 2012

Accepted: October 19, 2012

Published online: February 14, 2013

Processing time: 164 Days and 16.2 Hours

AIM: To report the largest patient cohort study investigating the diagnostic yield of intraductal ultrasound (IDUS) in indeterminate strictures of the common bile duct.

METHODS: A patient cohort with bile duct strictures of unknown etiology was examined by IDUS. Sensitivity, specificity and accuracy rates of IDUS were calculated relating to the definite diagnoses proved by histopathology or long-term follow-up in those patients who did not undergo surgery. Analysis of the endosonographic report allowed drawing conclusions with respect to the T and N staging in 147 patients. IDUS staging was compared to the postoperative histopathological staging data allowing calculation of sensitivity, specificity and accuracy rates for T and N stages. The endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography and IDUS procedures were performed under fluoroscopic guidance using a side-viewing duodenoscope (Olympus TJF 160, Olympus, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). All procedures were performed under conscious sedation (propofol combined with pethidine) according to the German guidelines. For IDUS, a 6 F or 8 F ultrasound miniprobe was employed with a radial scanner of 15-20 MHz at the tip of the probe (Aloka Co., Tokyo, Japan).

RESULTS: A total of 397 patients (210 males, 187 females, mean age 61.43 ± 13 years) with indeterminate bile duct strictures were included. Two hundred and sixty-four patients were referred to the department of surgery for operative exploration, thus surgical histopathological correlation was available for those patients. Out of 264 patients, 174 had malignant disease proven by surgery, in 90 patients benign disease was found. In these patients decision for surgical exploration was made due to suspicion for malignant disease in multimodal diagnostics (computed tomography scan, endoscopic ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging). Twenty benign bile duct strictures were misclassified by IDUS as malignant while 14 patients with malignant strictures were initially misdiagnosed by IDUS as benign resulting in sensitivity, specificity and accuracy rates of 93.2%, 89.5% and 91.4%, respectively. In the subgroup analysis of malignancy prediction, IDUS showed best performance in cholangiocellular carcinoma as underlying disease (sensitivity rate, 97.6%) followed by pancreatic carcinoma (93.8%), gallbladder cancer (88.9%) and ampullary cancer (80.8%). A total of 133 patients were not surgically explored. 32 patients had palliative therapy due to extended tumor disease in IDUS and other imaging modalities. Ninety-five patients had benign diagnosis by IDUS, forceps biopsy and radiographic imaging and were followed by a surveillance protocol with a follow-up of at least 12 mo; the mean follow-up was 39.7 mo. Tumor localization within the common bile duct did not have a significant influence on prediction of malignancy by IDUS. The accuracy rate for discriminating early T stage tumors (T1) was 84% while for T2 and T3 malignancies the accuracy rates were 73% and 71%, respectively. Relating to N0 and N1 staging, IDUS procedure achieved accuracy rates of 69% for N0 and N1, respectively. Limitations: Pre-test likelihood of 52% may not rule out bias and over-interpretation due to the clinical scenario or other prior performed imaging tests.

CONCLUSION: IDUS shows good results for accurate diagnostics of bile duct strictures of uncertain etiology thus allowing for adequate further clinical management.

- Citation: Meister T, Heinzow HS, Woestmeyer C, Lenz P, Menzel J, Kucharzik T, Domschke W, Domagk D. Intraductal ultrasound substantiates diagnostics of bile duct strictures of uncertain etiology. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(6): 874-881

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i6/874.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i6.874

There is still ongoing debate about adequate diagnostics in bile duct strictures of unknown etiology. The application of endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) is considered to be an essential tool in bile duct strictures in which additional need for intervention is given[1]. The main advantage of ERCP over other imaging modalities is the ability to achieve biliary decompression and to take transpapillary specimens for histological or cytological analysis in the very same session. A large trial on biliary brush cytology, however, described poor results thus indicating the need for further studies in the analysis of appropriate tissue sampling[2]. The use of intraductal ultrasound (IDUS) performed during ERCP enables the investigator to obtain additional information concerning the bile duct wall and the periductal tissue[3]. Specifically, IDUS gives clinically important data by visualizing the wall layers in biliary strictures and estimating the extent of potentially cancerous infiltration, also enabling the investigator to perform targeted biopsies. Thus, IDUS might be instrumental in choosing the appropriate therapeutic approach and may improve our potential to differentiate benign and malignant strictures. In this matter, however, previous studies, although partly of a prospective design, have only investigated limited numbers of patients[4-6]. On the other hand, cholangioscopy is at present time a promising diagnostic technique in diagnosing bile duct strictures of unknown origin. However, so far only limited data evaluating the diagnostic impact of cholangioscopy is available. In a prospective study with 35 patients included, the sensitivity of SpyGlass-directed biopsy of intraductal lesions was 71%[7,8].

In the present large cohort of patients, we aimed to evaluate the diagnostic yield of IDUS in patients scheduled for ERCP due to indeterminate strictures or filling defects of the common bile duct.

At the tertiary referral center of Münster University Hospital, we retrospectively analyzed the data of our patient cohort undergoing ERCP in combination with IDUS for diagnostics of indeterminate strictures of the bile duct during 2002-2009. All patients with bile duct stenosis who had undergone ERCP and IDUS during the study period could be identified by looking for codes K83.1 and procedures 3.055 and 1440.6 according to the International Classification of Diseases. A total of 397 patients were found in our analysis who were referred to the Department of Medicine B at Münster University Hospital. Clinical records of patients were collected and carefully analyzed. Baseline characteristics, diagnostic techniques employed and histopathology were retrieved as shown in Table 1.

| Baseline characteristics | |

| Patients (n) | 397 |

| Age (yr), mean ± SE | 61.43 ± 13 |

| Sex (M/F) | 210/187 |

| IDUS performed (n) | 397 |

| Follow-up (mo), mean ± SE | 39.7 ± 23.1 |

| Follow-up range (mo) | 12-100 |

| Procedures (n) | |

| Clinical follow-up | 95 |

| Surgery | 264 |

| Palliative therapy | 32 |

| Calculus extraction | 6 |

| Localization of stricture (CBD) | |

| Proximal third | 59 |

| Middle third | 46 |

| Distal third | 292 |

| Final diagnosis (n) | |

| Normal bile duct | 25 |

| Benign disease | |

| Papillitis | 30 |

| Ampullary adenoma | 18 |

| Cholangitis | 17 |

| PSC | 8 |

| Mirizzi syndrome | 7 |

| Choledocholithiasis | 14 |

| Pancreatitis | 59 |

| Pseudocyst | 4 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 1 |

| Papilloma of pancreatic duct | 3 |

| Choledochal cyst | 1 |

| Postoperative stenosis | 1 |

| Pancreatic cystadenoma | 2 |

| Caroli’s syndrome | 1 |

| Malignant disease | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 85 |

| Pancreatic carcinoma | 80 |

| Ampullary carcinoma | 26 |

| Gallbladder carcinoma | 9 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 6 |

Patients not having been histopathologically controlled by surgery, forceps biopsy or with an endoscopic follow-up < 1 year in suspected benign biliary stenosis were excluded from this study.

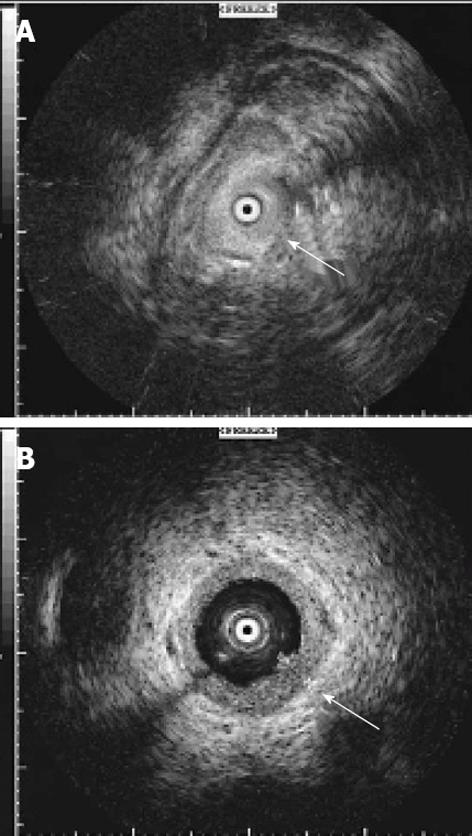

All 397 patients enrolled in the present study underwent ERCP with the additional application of intraductal ultrasound. In our cohort, there was no case in which a positive tissue diagnosis was already known at the time of IDUS investigation. The individual procedure was performed after written informed consent had been obtained from the patients or related persons for the endoscopic procedures. All endoscopic maneuvers were executed by highly experienced investigators according to the generally accepted guidelines with an ERCP case volume above 200/year[9]. The ERCP and IDUS procedures were performed under fluoroscopic guidance using a side-viewing duodenoscope (Olympus TJF 160, Olympus, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). All procedures were performed under conscious sedation (propofol combined with pethidine) according to the German guidelines[10]. For IDUS, a 6 F or 8 F ultrasound miniprobe was employed with a radial scanner of 15-20 MHz at the tip of the probe (Aloka Co., Tokyo, Japan). Thus a radial real-time image of 360° view was possible for optimum investigation of the area surrounding the probe. The visible depth was about 20 mm with a resolution of up to 0.1 mm (Figure 1). Three hundred and twelve IDUS procedures included additional forceps biopsies. Endoscopic transpapillary biopsies (n = 4-8 specimens) were taken out of the biliary strictures by straight or angled endoscopic forceps (MTW Endoscopy, Wesel, Germany). If insertion of the forceps into the stricture was not feasible, biopsies were retrieved from the distal margins of the bile duct stenosis[11]. Patients with eligibility for surgery were transferred to the Department of General Surgery, Münster University Hospital.

Two hundred and sixty-four patients were surgically explored (66% of patients). In 174 cases malignancy was proven, of those 14 patients were initially misdiagnosed by IDUS as benign, thus in these cases uT stages were not available. Thirteen of the 174 patients had surgical exploration but due to extended disease with inoperability T and N stage assessment was not done. Thus, retrospective analysis of the endosonographic report allowed drawing conclusions with respect to the T and N staging in 147 patients. IDUS staging was based on the latest TNM classification system[12]. IDUS classification of N stages was as follows: N0-no regional lymph node metastasis; N1-regional lymph node metastasis. Lymph nodes were considered positive, if at least one of the following criteria could be assessed: lymph node larger than 10 mm, delineated borders, hypoechoic structure resembling the primary tumor, roundish shape.

IDUS staging was compared to the postoperative histopathological staging data allowing calculation of sensitivity, specificity and accuracy rates for T and N stages. Due to the limited penetration depth of IDUS, M staging was not performed.

All patients with suspected benign strictures had routine follow-up the day following intervention as well as every three months the first year, every 6 mo the second year and annually up to the third year after intervention at our department. The follow-up procedure was performed according to a surveillance protocol and included laboratory testing and abdominal ultrasound. In cases of biliary plastic stent insertion, the follow-up procedures included ERCP and where appropriate biliary plastic stent changing.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 17.0 (Chicago, IL, United States). Results were expressed as medians and ranges. For each of the diagnostic measures, sensitivity, specificity and accuracy rates were calculated for each individual T and N stage. In all cases, gold standard was the histopathologic staging of specimens. Comparison of accuracy rates between groups (localization of stricture) was performed by using the Mann-Whitney U test and the χ2 test as appropriate. Differences were considered statistically significant if P < 0.05. For statistical analysis, sensitivity, specificity, pre-test likelihood and accuracy rates were calculated as follows: sensitivity = true positives/(true positives + false negatives); specificity = true negatives/(true negatives + false positives); pre-test likelihood = truly malignant cases/total cases; accuracy = (true positives + true negatives)/total cases.

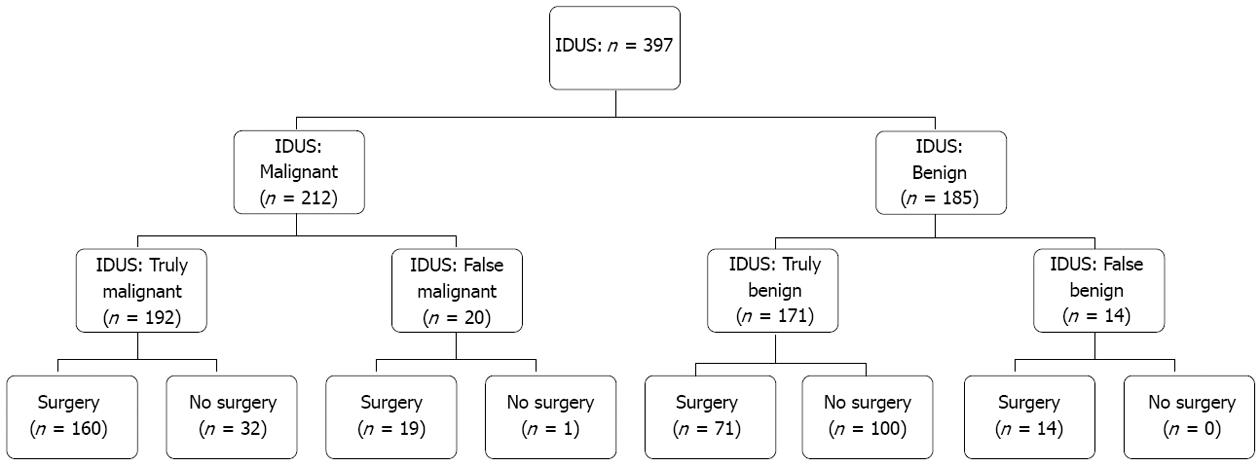

The study cohort included 397 patients (210 men and 187 women; median age 61.4 ± 13 years). Two hundred and sixty-four patients were referred to the department of surgery for operative exploration, thus surgical histopathological correlation was available for those patients. Out of 264 patients, 174 had malignant disease proven by surgery, in 90 patients benign disease was found. In these patients decision for surgical exploration was made due to suspicion for malignant disease in multimodal diagnostics [computed tomography (CT) scan, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)]. A total of 133 patients were not surgically explored. Thirty-two patients had palliative therapy due to extended tumor disease in IDUS and other imaging modalities. In 6 patients calculus extraction was performed due to choledocholithiasis. Ninety-five patients had benign diagnosis by IDUS, forceps biopsy and radiographic imaging and were followed by a surveillance protocol with a follow-up of at least 12 mo; the mean follow-up was 39.7 mo (Table 1). A flow chart showing the enrollment of the study patients with distribution based on IDUS diagnosis is presented in Figure 2.

IDUS was performed in all patients enrolled. Pre-test likelihood for malignant stenosis in our patient cohort of 52% (95%CI: 47%-57%) was calculated. Twenty benign bile duct strictures were initially misclassified by IDUS as malignant while 14 malignant bile duct strictures were initially interpreted by IDUS as benign resulting in sensitivity, specificity and accuracy rates of 93.2%, 89.5% and 91.4%, respectively (Tables 2 and 3). In the subgroup analysis of malignancy prediction, IDUS showed best performance in cholangiocellular carcinoma as underlying disease (sensitivity rate, 97.6%) followed by pancreatic carcinoma (93.8%), gallbladder cancer (88.9%) and ampullary cancer (80.8%) (Tables 2 and 3).

| Final diagnosis according to histopathology or long-term follow-up | |||||||

| Method, classification | Benign lesion | Carcinoma | CCC | Pancreatic CA | Ampullar CA | GB CA | HCC |

| IDUS, benign | 171 | 14 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| IDUS, malignant | 20 | 192 | 83 | 75 | 21 | 8 | 5 |

| Tumor | Sensitivity (95%CI) | Specificity (95%CI) | Accuracy (95%CI) |

| All tumors | 0.93 (0.90-0.97) | 0.89 (0.85-0.94) | 0.91 (0.89-0.94) |

| CCC | 0.98 (0.94-1.0) | 0.98 (0.94-1.0) | 0.92 (0.89-0.95) |

| Pancreatic CA | 0.94 (0.88-0.99) | 0.90 (0.85-0.94) | 0.91 (0.87-0.94) |

| Ampullary CA | 0.81 (0.66-0.96) | 0.90 (0.85-0.94) | 0.89 (0.84-0.93) |

| GB CA | 0.89 (0.68-1.0) | 0.90 (0.85-0.94) | 0.90 (0.85-0.94) |

| HCC | 0.83 (0.54-1.0) | 0.90 (0.85-0.94) | 0.89 (0.85-0.94) |

Accuracy rates of IDUS for malignant stenoses in the proximal, middle or distal third of the common bile duct did not differ statistically in terms of localization (Table 4).

| Localization of stenosis | N | Accuracy (95%CI) | Test for significance | P value |

| Proximal third | 55/59 | 0.93 (0.87-1.0) | Proximal vs middle third | 0.958 |

| Middle third | 43/46 | 0.93 (0.87-1.0) | Proximal vs distal third | 0.280 |

| Distal third | 260/292 | 0.89 (0.85-0.93) | Middle vs distal third | 0.308 |

Overall T and N staging results with the intraductal ultrasound miniprobe are given in Tables 5 and 6. The accuracy rate for discriminating early T stage tumors (T1) was 84% while for T2 and T3 malignancies the accuracy rates were 73% and 71%, respectively (Table 5). Relating to N0 and N1 staging, IDUS achieved accuracy rates of 69% each (Table 6).

| Histopathology | ||||

| IDUS | pT1 | pT2 | pT3/4 | ∑ |

| uT1 | 12 | 9 | 13 | 34 |

| uT2 | 1 | 26 | 24 | 51 |

| uT3 | 1 | 5 | 56 | 62 |

| ∑ | 14 | 40 | 93 | 147 |

| Sensitivity (95%CI) | 0.86 (0.67-1.0) | 0.65 (0.50-0.80) | 0.60 (0.50-0.70) | |

| Specificity (95%CI) | 0.83 (0.77-0.90) | 0.77 (0.69-0.85) | 0.89 (0.81-0.97) | |

| Accuracy (95%CI) | 0.84 (0.78-0.89) | 0.73 (0.66-0.81) | 0.71 (0.63-0.78) | |

| Histopathology | |||

| IDUS | pN0 | pN1 | ∑ |

| uN0 | 44 | 23 | 67 |

| uN1 | 23 | 57 | 80 |

| ∑ | 67 | 80 | 147 |

| Sensitivity (95%CI) | 0.66 (0.61-0.81) | 0.61 (0.57-0.79) | |

| Specificity (95%CI) | 0.61 (0.54-0.77) | 0.66 (0.54-0.77) | |

| Accuracy (95%CI) | 0.69 (0.61-0.76) | 0.69 (0.61-0.76) | |

Endoscopic ultrasound has proved to be an accurate imaging device in the diagnostics and staging of malignant bile duct strictures[13]. However, in previous studies, although partly of a prospective design, only limited numbers of patients were investigated[4-6]. Therefore, in the present to our knowledge largest patient cohort, we aimed to substantiate the diagnostic yield of IDUS.

IDUS has also proved superior to other imaging modalities such as CT and MRI[14-16]. Its limitation, however, is the minor ultrasonic penetration depth. Consequently, intraductal ultrasonography tends to understage tumors of the pancreaticobiliary tract. Therefore, IDUS does not seem useful in extensive lymph node staging[17].

It is consistently accepted that in the bilio-pancreatic tract depiction of tumors by means of ultrasound and CT is difficult, but these tumors can appropriately be represented through endoscopic ultrasound[18] or IDUS[19,20]. Although IDUS is superior to EUS regarding diagnostics of tumor extension in the pancreatic and biliary duct, the use of IDUS has not been taken up widely yet.

A promising diagnostic tool in the differentiation of bile duct strictures is single- operator peroral cholangioscopy (SOC) as it provides direct visualization of the bile duct and facilitates diagnostic procedures and therapeutic intervention. The diagnostic utility of SOC for indeterminate biliary lesions has been the topic of a few recently published studies[21,22].

However, only limited data with smaller patient cohorts exist. Promising results with an accuracy of SOC for diagnosing malignant lesions has been reported to range between 64% and 89%. SOC-guided biopsies have been shown to be adequate in 72% to 82%[21-23]. Therefore, its therapeutic and diagnostic yield in patients with bile duct strictures remains uncertain. A prospective randomized trial comparing various endoscopic imaging and radiographic imaging modalities with each other would be desirable, especially in a multi-center study design.

In our patient cohort of 397 patients with bile duct strictures of initially unknown etiology, using IDUS we observed sensitivity, specificity and accuracy rates of 93%, 89% and 91%, respectively, for discriminating malignant from benign lesions. In previous studies with a limited number of patients, IDUS accuracy rates between 84% and 95% are described as presented in Table 7. IDUS also showed excellent results in regard to localization of biliary stenoses with an accuracy rate of 93% (proximal part of bile duct), 93% (middle) and 89% (distal), respectively (P values not significant) (Table 4). In our study, endoscopic transpapillary biopsies (ETP) were additionally obtained in 312 cases. Out of 226 bile duct strictures initially diagnosed to be benign by ETP, 101 cases eventually turned out as malignancies. There were no false-positive results in forceps biopsy histopathology leading to sensitivity, specificity and accuracy rates of 46%, 100% and 67.6%, respectively[11]. Thus the authors conclude that ETPs are of limited value for detecting additional malignant bile duct strictures.

In matters of tumor entity, IDUS demonstrated best results in cholangiocellular carcinoma (CCC) with accuracy and sensitivity rates of 92% and 98%, respectively. As far as T staging is concerned, upon IDUS the normal bile duct wall appears as either two or three layers. However, in some patients differentiation of the fibromuscular layer from the perimuscular connective tissue can be difficult thus limiting the ability to distinguish CCC stages 1 and 2, although this distinction is usually not clinically relevant with respect to treatment options[24]. According to a study conducted earlier by our group[25], the various layers of the extrahepatic bile duct wall as described by the Union for International Cancer Control 7th tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification[12] are not consistently demonstrable histomorphologically, immunohistochemically or by endosonographic imaging. Domagk et al[25] suggested that difficulties in distinguishing tumor invasion encroaching beyond the bile duct (T2) and into the pancreas (T3) pose problems for the present TNM-classification. A better metric may be to combine T2- and T3-staged tumors into one single class.

T staging of other tumor entities such as pancreatic, ampullary or gallbladder cancer may be limited in miniprobe intraductal ultrasound due to its maximum penetration depth of 20 mm. The T stage, e.g., of pancreatic tumors among other factors relies on tumor size. Further, the assessment of vascular tumor infiltration is restricted due to the technical limitation of penetration depth and absence of potential duplex sonography. In a study by Tamada et al[26,27], vascular infiltration of CCC was assessed: Depiction of the right hepatic artery was possible in 100% of the cases while in less than 20% of the cases depiction of the common hepatic artery or the left hepatic artery succeeded. On that account, the assessment of tumor infiltration into the above mentioned vessels was inaccurate.

In summary, IDUS tends to understage tumors of the pancreaticobiliary tract. Specific analysis of our patient cohort revealed overall T staging accuracy rates as follows: T1 84%, T2 73% and T3/T4 71% as displayed in Table 5. N staging accuracy was calculated as 69% (Table 6).

In recent years, other imaging techniques like magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreatography (MRCP) and multi-detector computed tomography have also been evaluated for their diagnostic sensitivity and specificity in biliary duct tumors. In a first prospective comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of ERCP, MRCP, CT and EUS in biliary duct strictures by Rösch et al[28], 50 patients were analyzed. In their patient cohort, relating to diagnosis of malignancy sensitivity and specificity rates of 85%/75% for ERCP/PTC, 85%/71% for MRCP, 77%/63% for CT, and 79%/62% for EUS were observed. Those authors concluded that although MRCP provides the same imaging information as direct cholangiography, it has only limited specificity for the diagnosis of malignant strictures[28]. A prospective study by our group confirmed superiority of ERCP supplemented by IDUS in differentiating benign from malignant strictures as compared with MRI[29]. Classification of T stages by endolumenal ultrasound was also the topic of an investigation conducted by Menzel et al[15] demonstrating similar accuracy rates (77.7%) for T staging as shown in the present study.

Admittedly, as limitations of the present study the retrospective design and certain bias have to be mentioned. In our cohort, there was no case in which a positive tissue diagnosis was already known at the time of IDUS investigation but our pre-test likelihood of 52% may not rule out bias and over-interpretation due to the clinical scenario or other prior performed imaging tests. Our patient cohort is certainly a highly selected one making the probability of malignant bile duct stricture more obvious. On the one hand, the prevalence of malignancy in our patient cohort was 52% as expressed by the pre-test likelihood. On the other hand, the accuracy of IDUS for detecting malignant bile duct strictures exceeds 91%. Therefore, our analysis of a very large patient cohort shows good results of IDUS with regard to accurate diagnostics of bile duct strictures of uncertain etiology and, thus, allows for adequate further clinical management. In particular, IDUS is suitable for early T stage prediction.

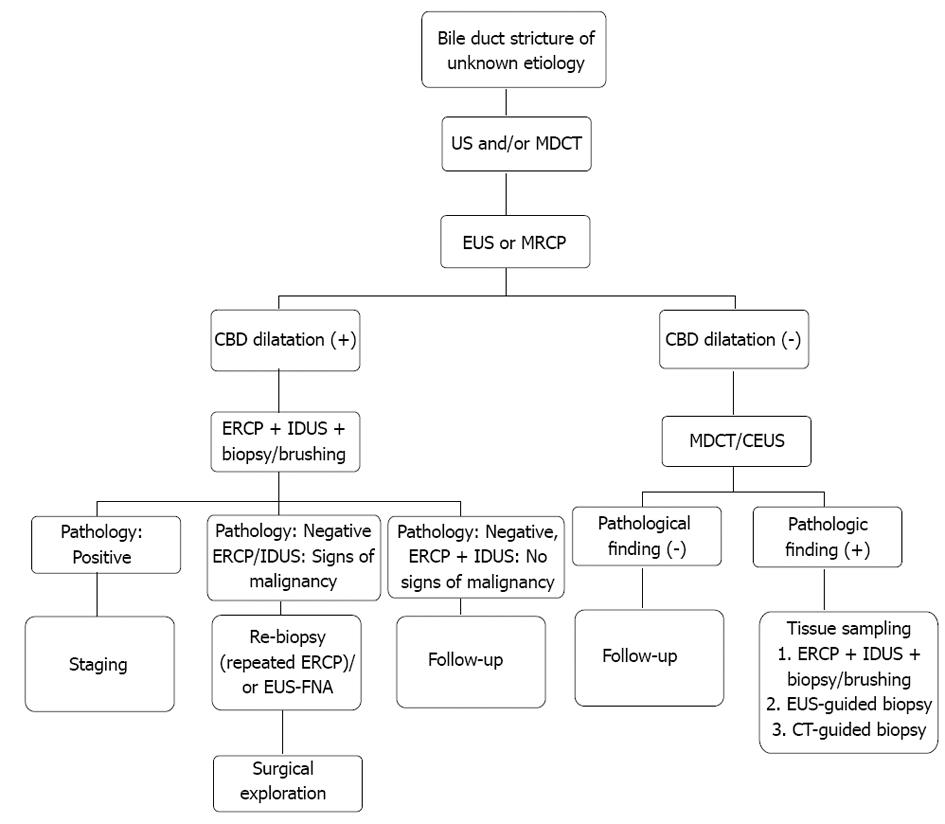

Summing up, we suggest the following algorithm for the evaluation of bile duct strictures of uncertain etiology as displayed in Figure 3.

Thanks to Professor Gary L Powell for helpful and valuable suggestions regarding the manuscript and true friendship for over 25 years.

Adequate diagnostics in bile duct strictures of unknown etiology is still a challenging task. Many different imaging techniques compete with each other. Intraductal ultrasound (IDUS) might be instrumental in choosing the appropriate therapeutic approach and may improve our potential to differentiate benign and malignant strictures.

The authors undertook the largest European retrospective study to evaluate the diagnostic yield of IDUS in patients scheduled for endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography due to indeterminate strictures of the common bile duct.

IDUS shows good results for accurate diagnostics of bile duct strictures of uncertain etiology thus allowing for adequate further clinical management. In particular, IDUS is suitable for early T stage prediction.

By analyzing the accuracy of IDUS in the diagnostics of bile duct strictures of uncertain etiology, the authors contribute to a better diagnostic strategy of this difficult issue. This may lead to an improved patient care with an optimal diagnostic approach to patients with bile duct strictures of uncertain etiology.

IDUS enables the investigation of the common bile duct wall and the periductal tissue with high resolution.

Authors evaluated the role of IDUS in the differential diagnosis of indeterminate biliary strictures. This retrospective study involved such a large number of patients with surgical standards. It is a well-written paper, in which the authors have studied an important issue in hepatobiliary medicine.

| 1. | Choudari CP, Fogel E, Gottlieb K, Sherman S, Lehman GA. Therapeutic biliary endoscopy. Endoscopy. 1998;30:163-173. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Glasbrenner B, Ardan M, Boeck W, Preclik G, Möller P, Adler G. Prospective evaluation of brush cytology of biliary strictures during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Endoscopy. 1999;31:712-717. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Menzel J, Domschke W. Intraductal ultrasonography (IDUS) of the pancreato-biliary duct system. Personal experience and review of literature. Eur J Ultrasound. 1999;10:105-115. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Farrell RJ, Agarwal B, Brandwein SL, Underhill J, Chuttani R, Pleskow DK. Intraductal US is a useful adjunct to ERCP for distinguishing malignant from benign biliary strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:681-687. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Levy MJ, Baron TH, Clayton AC, Enders FB, Gostout CJ, Halling KC, Kipp BR, Petersen BT, Roberts LR, Rumalla A. Prospective evaluation of advanced molecular markers and imaging techniques in patients with indeterminate bile duct strictures. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1263-1273. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Vazquez-Sequeiros E, Baron TH, Clain JE, Gostout CJ, Norton ID, Petersen BT, Levy MJ, Jondal ML, Wiersema MJ. Evaluation of indeterminate bile duct strictures by intraductal US. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:372-379. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Chen YK, Pleskow DK. SpyGlass single-operator peroral cholangiopancreatoscopy system for the diagnosis and therapy of bile-duct disorders: a clinical feasibility study (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:832-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 310] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tamada K, Ushio J, Sugano K. Endoscopic diagnosis of extrahepatic bile duct carcinoma: Advances and current limitations. World J Clin Oncol. 2011;2:203-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Faigel DO, Baron TH, Lewis B, Petersen B, Petrini J. Ensuring competence in endoscopy. Prepared by the ASGE taskforce on ensuring competence in endoscopy and American College of Gastroenterology executive and practice management committees. ASGE policy and procedures manual for gastrointestinal endoscopy: guidelines for training and practice on CD-ROM. ASGE. 2005;1-36. |

| 10. | Riphaus A, Wehrmann T, Weber B, Arnold J, Beilenhoff U, Bitter H, von Delius S, Domagk D, Ehlers A, Faiss S. S3 Guideline: Sedation for gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2009;41:787-815. |

| 11. | Heinzow H, Woestmeyer C, Domschke W, Domagk D, Meister T. Endoscopic transpapillary biopsies are of limited value in the diagnostics of bile duct strictures of unknown etiology - results of a histopathologically controlled study in 312 patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;In press. |

| 12. | Edge S, Byrd D, Compton C, Fritz A, Greene F, Trotti A. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer-Verlag 2010; . |

| 13. | Rösch T, Lorenz R, Braig C, Classen M. Endoscopic ultrasonography in diagnosis and staging of pancreatic and biliary tumors. Endoscopy. 1992;24 Suppl 1:304-308. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Domagk D, Poremba C, Dietl KH, Senninger N, Heinecke A, Domschke W, Menzel J. Endoscopic transpapillary biopsies and intraductal ultrasonography in the diagnostics of bile duct strictures: a prospective study. Gut. 2002;51:240-244. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Menzel J, Poremba C, Dietl KH, Domschke W. Preoperative diagnosis of bile duct strictures--comparison of intraductal ultrasonography with conventional endosonography. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:77-82. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Tamada K, Ido K, Ueno N, Kimura K, Ichiyama M, Tomiyama T. Preoperative staging of extrahepatic bile duct cancer with intraductal ultrasonography. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:239-246. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Menzel J, Domschke W. Gastrointestinal miniprobe sonography: the current status. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:605-616. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Meyer J, Sulkowski U, Preusser P, Bünte H. Clinical aspects and surgical therapy of papillary cancer. Zentralbl Chir. 1987;112:20-26. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Itoh A, Goto H, Naitoh Y, Hirooka Y, Furukawa T, Hayakawa T. Intraductal ultrasonography in diagnosing tumor extension of cancer of the papilla of Vater. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:251-260. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Menzel J, Hoepffner N, Sulkowski U, Reimer P, Heinecke A, Poremba C, Domschke W. Polypoid tumors of the major duodenal papilla: preoperative staging with intraductal US, EUS, and CT--a prospective, histopathologically controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:349-357. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Kalaitzakis E, Webster GJ, Oppong KW, Kallis Y, Vlavianos P, Huggett M, Dawwas MF, Lekharaju V, Hatfield A, Westaby D. Diagnostic and therapeutic utility of single-operator peroral cholangioscopy for indeterminate biliary lesions and bile duct stones. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:656-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Ramchandani M, Reddy DN, Gupta R, Lakhtakia S, Tandan M, Darisetty S, Sekaran A, Rao GV. Role of single-operator peroral cholangioscopy in the diagnosis of indeterminate biliary lesions: a single-center, prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:511-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Siddiqui AA, Mehendiratta V, Jackson W, Loren DE, Kowalski TE, Eloubeidi MA. Identification of cholangiocarcinoma by using the Spyglass Spyscope system for peroral cholangioscopy and biopsy collection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:466-471; quiz e48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tamada K, Kanai N, Ueno N, Ichiyama M, Tomiyama T, Wada S, Oohashi A, Nishizono T, Tano S, Aizawa T. Limitations of intraductal ultrasonography in differentiating between bile duct cancer in stage T1 and stage T2: in-vitro and in-vivo studies. Endoscopy. 1997;29:721-725. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Domagk D, Diallo R, Menzel J, Schleicher C, Bankfalvi A, Gabbert HE, Domschke W, Poremba C. Endosonographic and histopathological staging of extrahepatic bile duct cancer: time to leave the present TNM-classification? Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:594-600. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Tamada K, Ido K, Ueno N, Ichiyama M, Tomiyama T, Nishizono T, Wada S, Noda T, Tano S, Aizawa T. Assessment of hepatic artery invasion by bile duct cancer using intraductal ultrasonography. Endoscopy. 1995;27:579-583. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Tamada K, Ido K, Ueno N, Ichiyama M, Tomiyama T, Nishizono T, Wada S, Noda T, Tano S, Aizawa T. Assessment of portal vein invasion by bile duct cancer using intraductal ultrasonography. Endoscopy. 1995;27:573-578. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Rösch T, Meining A, Frühmorgen S, Zillinger C, Schusdziarra V, Hellerhoff K, Classen M, Helmberger H. A prospective comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of ERCP, MRCP, CT, and EUS in biliary strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:870-876. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Domagk D, Wessling J, Conrad B, Fischbach R, Schleicher C, Böcker W, Senninger N, Heinecke A, Heindel W, Domschke W. Which imaging modalities should be used for biliary strictures of unknown aetiology? Gut. 2007;56:1032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tamada K, Nagai H, Yasuda Y, Tomiyama T, Ohashi A, Wada S, Kanai N, Satoh Y, Ido K, Sugano K. Transpapillary intraductal US prior to biliary drainage in the assessment of longitudinal spread of extrahepatic bile duct carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:300-307. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Domagk D, Wessling J, Reimer P, Hertel L, Poremba C, Senninger N, Heinecke A, Domschke W, Menzel J. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, intraductal ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in bile duct strictures: a prospective comparison of imaging diagnostics with histopathological correlation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1684-1689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewers Sharma M, Mehrabi A, Oh HC S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY