INTRODUCTION

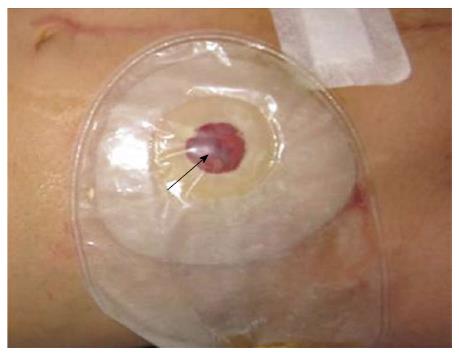

Varices are a common complication of liver cirrhosis with portal hypertension. Typically, they are found in the gastro-esophageal region. Ectopic varices are rare, and can arise along the entire gastrointestinal tract, including the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, colon and rectum, but seldom at the umbilicus, in the peritoneum and stomas[1,2]. Ectopic varices can present with hemorrhage, accounting for up to 5% of all variceal bleeding[1]. However, due to the difficulty in their diagnosis and treatment, the mortality secondary to their initial bleeding is up to 40%[3]. Currently, reports on ectopic variceal bleeding are mostly located in the gut, especially in the duodenum and rectum. Variceal bleeding from a stoma, especially from an ileal conduit stoma, has rarely been reported[4]. Here, we present a case of ectopic variceal bleeding from an ileal conduit stoma (Figure 1) which was successfully managed by endovascular embolization via the transjugular transhepatic approach.

Figure 1 The bluish ectopic varices at the ileal conduit stoma (black arrow).

CASE REPORT

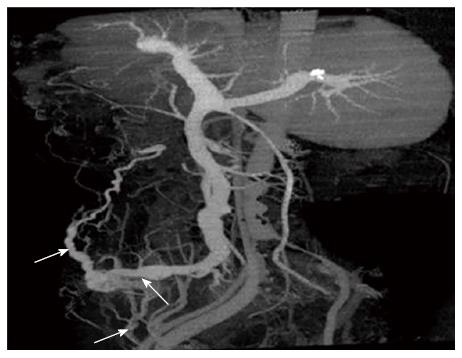

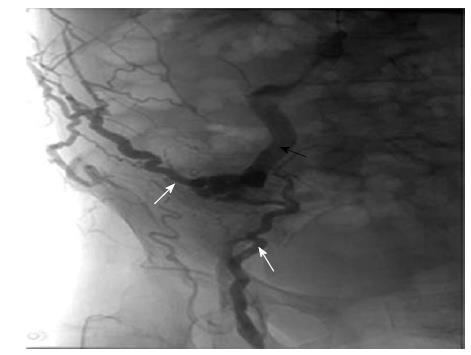

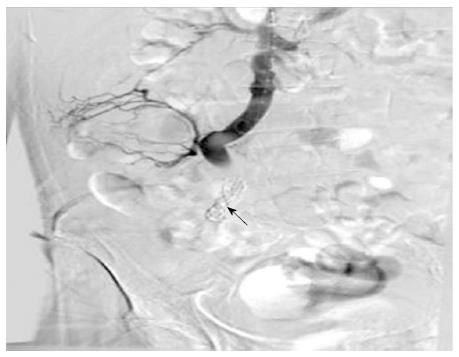

A 70-year-old woman, who had undergone cystectomy and an ileal conduit due to interstitial cystitis two years before, presented with chronic bleeding from the ileal conduit stoma after the operation. The patient also had drug-induced liver cirrhosis and a history of two episodes of hepatic encephalopathy. The bleeding was first considered to be wound bleeding and was treated with homeostatic drugs. However, the hemorrhage persisted, and an enhanced multislice computed tomography (CT) scan and 3-dimensional (3D) reconstruction imaging showed ectopic varices fed by the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) and communicated to the paraumbilical vein and femoral vein at the ileal conduit ostomy (Figure 2). The hemorrhage could be paused by local compression. Two weeks previously, with the bleeding worsening, local compression and vasoactive therapy (Octreotide 50 mg/h) failed to achieve hemostasis. A wound resuture was then performed, however, the result was disappointing. Three days before, massive hemorrhage had occurred and the patient developed hemorrhagic shock (systolic blood pressure 88 mmHg, heart rate 103/min) and became severely anemia (hemoglobin 57 g/L, red blood cell 2.14 × 1012/L). The platelets, prothrombin time and international normalized ratio were 78 × 109/L, 18.6 s, and 1.18, respectively. Considering her hepatic function [Child-Pugh B (9 score)], abundant ascites and her history of recurrent hepatic encephalopathy, an emergency transjugular transhepatic embolization was planned. Portal venography and peripheral superior mesenteric venography demonstrated varices arising from the SMV with retrograde flow toward the stoma and communicated to the paraumbilical vein and femoral vein (Figure 3). The portal-pressure gradient measured during surgery was 18 cmH2O. Ectopic varices embolization with a stainless steel coil was then performed. The portal-pressure gradient measured after the operation was 19 cmH2O, and postoperative opacification showed that the varices had disappeared (Figure 4). The patient had no complications following the procedure and received conservative medical therapy with Propranolol after the operation. Follow-up at 4 mo showed no focal bleeding.

Figure 2 Three-dimensional reconstruction showed the ectopic varices (black arrow) at the ileal conduit stoma fed by the superior mesenteric vein (white arrow) and communicated to the paraumbilical vein (white arrow) and femoral vein (white arrow).

Figure 3 Opacification showed the varices fed by the superior mesenteric vein (black arrow) and communicated to the paraumbilical vein and femoral vein (white arrows).

Figure 4 Opacification showed disappearance of the ileal conduit stoma varices and colis (black arrow) in the ectopic varices.

DISCUSSION

Reports on the hemorrhage of ectopic varices are limited, and most are of digestive tract bleeding or umbilical vein bleeding[5-9]. Abdominal intestinal ostomy may result in the formation of collateral vessels at the stoma, such as the development of ileostomy stomal varices after ileal conduit ostomy and ileostomy in several case reports[4,10,11]. The patient in this study developed ileal conduit stomal variceal bleeding. Due to persistent hemorrhage, a contrast enhanced multislice CT scan and 3D reconstruction imaging were performed which revealed ectopic varices fed by the SMV and communicated to the paraumbilical vein and femoral vein at the stoma. The correct diagnosis of variceal bleeding with portal hypertension was made.

The standard therapy for ectopic variceal bleeding has not yet been determined, and a recent review[12] recommended that management should include medical conservative therapy, endoscopic therapy, interventional therapy, surgical shunt or liver transplantation. Similar to variceal bleeding from the esophageal-gastric region, sclerotherapy or band ligation of the varices are theoretically feasible. However, because of potential necrosis and perforation following sclerotherapy, and a high risk of massive hemorrhage following sloughing of the occluded varices after band ligation, and persistence of portal hypertension, the results of this treatment modality were disappointing[13], especially in stomal variceal bleeding[11]. Our patient was treated with ectopic varices suture ligation, however, bleeding did not stop. As transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt (TIPS) alone or in combination with variceal embolization has demonstrated effectiveness for the hemostasis of ectopic variceal bleeding in patients with portal hypertension in some studies[14,15], it seemed appropriate that our patient should be treated with this modality. However, the current common understanding of TIPS shunt creation for hemostasis is that it increases the incidence of hepatic encephalopathy and damages liver function. Our patient had a history of recurrent hepatic encephalopathy, thus, the TIPS shunt was not applicable in this patient. Surgical shunts have been shown to be effective in preventing hemorrhage recurrence, but are associated with mortality ranging from 1% to 50%, and many patients are not healthy enough to endure the operation[11]. Our patient had hemorrhagic shock, therefore it was clearly unwise to choose this treatment modality. Thus, embolization of the ectopic varices was the best choice for this patient. Usually, varices embolization can be managed via the percutaneous transhepatic[16-18] or transjugular transhepatic route[4]. Hemoperitoneum is the most common complication of percutaneous transhepatic embolization[18], other complications include bile leak, liver trauma, and portal thrombosis[17]. As the patient had abundant ascites and we had successfully performed thousands of TIPS procedures, endovascular embolization of the stomal varices via the transjugular transhepatic route for hemostasis was the appropriate therapy in this case. The varices were occluded after the procedure and no complications occurred during the procedure. No focal bleeding was observed after four months of follow-up.

In conclusion, although rare, when a patient with ileal conduit stoma presents with persistent stomal bleeding, ectopic variceal bleeding from the ileal conduit should be considered. Endovascular embolization via the transjugular transhepatic approach is a reasonable choice in patients with stomal variceal bleeding which failed conservative therapy and local resuture, especially in an emergency situation.