Published online Oct 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i40.6928

Revised: July 31, 2013

Accepted: August 17, 2013

Published online: October 28, 2013

Processing time: 160 Days and 6.7 Hours

Collagenous sprue (CS) is a pattern of small-bowel injury characterized histologically by marked villous blunting, intraepithelial lymphocytes, and thickened sub-epithelial collagen table. Clinically, patients present with diarrhea, abdominal pain, malabsorption, and weight loss. Gluten intolerance is the most common cause of villous blunting in the duodenum; however, in a recent case series by the Mayo Clinic, it has been reported that olmesartan can have a similar effect. In this case report, a 62-year-old female with a history of hypothyroidism and hypertension managed for several years with olmesartan presented with abdominal pain, weight loss, and nausea. Despite compliance to a gluten-free diet, the patient’s symptoms worsened, losing 20 pounds in 3 wk. Endoscopy showed thickening, scalloping, and mosaiform changes of the duodenal mucosa. The biopsy showed CS characterized by complete villous atrophy, lymphocytosis, and thickened sub-epithelial collagen table. After 2 mo cessation of olmesartan, the patient’s symptoms improved, and follow-up endoscopy was normal with complete villous regeneration. These findings suggest that olmesartan was a contributing factor in the etiology of this patient’s CS. Clinicians should be aware of the possibility of drug-induced CS and potential reversibility after discontinuation of medication.

Core tip: Collagenous sprue (CS) is a pattern of small-bowel injury characterized histologically by marked villous blunting, intraepithelial lymphocytes, and thickened sub-epithelial collagen table. Clinically, patients present with diarrhea, abdominal pain, malabsorption, and weight loss, which raises suspicion of celiac disease. Clinicians should be aware of the possibility of drug-induced CS and potential reversibility after discontinuation of medication.

- Citation: Nielsen JA, Steephen A, Lewin M. Angiotensin-II inhibitor (olmesartan)-induced collagenous sprue with resolution following discontinuation of drug. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(40): 6928-6930

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i40/6928.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i40.6928

Collagenous sprue (CS) is a pattern of small-bowel injury characterized histologically by marked villous blunting, increased intraepithelial lymphocytes, and thickened collagen table. Clinically, patients present with diarrhea, abdominal pain, malabsorption, and subsequent weight loss. Gluten intolerance is the most common cause of villous blunting in the duodenum; however, in contrast to celiac disease, many patients with CS do not respond to a gluten-free diet[1]. Recently, the Mayo Clinic reported in a series of 22 cases that olmesartan can cause a similar severe spruelike enteropathy[2]. We report one such case of a woman who had been managing her hypertension with olmesartan for the previous couple years.

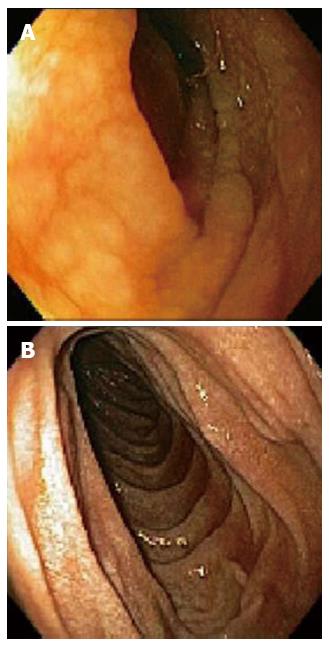

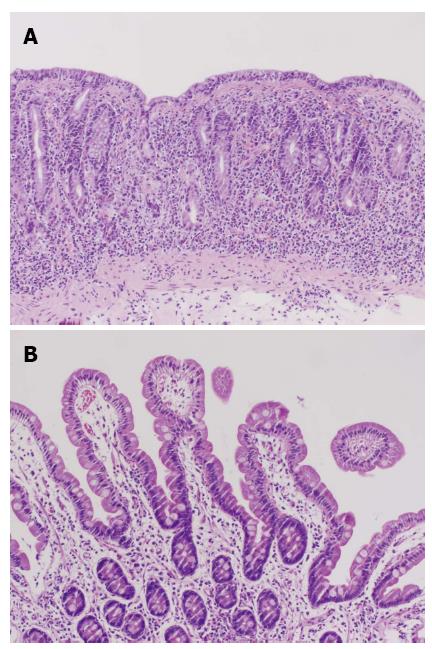

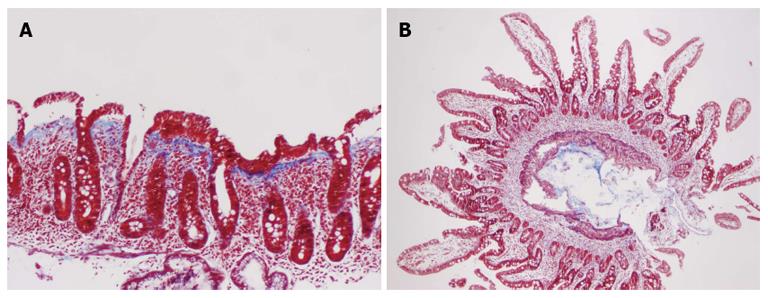

A 62-year-old female with a history of hypothyroidism and hypertension presented with abdominal pain, weight loss, change in bowel habits, nausea, and increased bloating/gas; she denied any new medications or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs use. Initial endoscopy was normal; however, the histologic findings showed a CS characterized by complete villous atrophy, up to 100 intraepithelial lymphocytes per 100 epithelial cells, and focally thickened sub-epithelial collagen table. Immunohistochemical stains showed prevalent CD3 positive intraepithelial lymphocytes with no evidence of lymphoma. Celiac markers and anti-enterocyte antibodies were negative; however, histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DQ2 was present. Despite compliance to a gluten-free diet, the patient’s symptoms worsened, losing 20 pounds in 3 wk. A second esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) showed thickening and scalloping of duodenal mucosa (Figure 1A). Subsequent histology revealed increased thickness of the collagen band, compared to the previous biopsies, persistent complete villous blunting, and intra-epithelial lymphocytosis (Figures 2A and 3A). A few days later, the patient was admitted to the Emergency Department for bloody stools and advised to discontinue taking olmesartan because her blood pressure was “normotensive”. After cessation of olmesartan the patient’s symptoms improved, and 3 mo later EGD (Figure 1B) and biopsy findings were normal, with histologic examination demonstrating complete villous regeneration in the duodenum (Figures 2B and 3B). These findings suggest that olmesartan was a contributing factor in the etiology of this patient’s CS.

Many authors still regard CS as a part of the spectrum of celiac disease and designate non-responsive patients as being a “refractory sprue”[3]. Both infectious agents and allergic reactions are speculated to be involved in the mucosal injury for a CS, but the etiology and pathogenesis are still unknown[4]. Previous accounts of non-gluten sensitivity-related small bowel villous flattening have been reported. In one case series, seven patients all experienced symptoms suggestive of gluten sensitivity and had morphologically-similar mucosal injury in their small bowel biopsy specimens. Regardless of their gluten consumption, all patients experienced clinical improvement and mucosal regeneration. The cause and resolution of their injury is unknown, demonstrating that celiac sprue is not the only disease which can cause villous blunting[4].

In a recent study at Mayo Clinic, 22 patients with unexplained chronic diarrhea and enteropathy and no response to treatments for celiac disease experienced clinical improvement after suspension of olmesartan. All patients had either partial or total duodenal villous atrophy, 6 of which showed a thickened collagen table. Additionally, 7 patients had collagenous or lymphocytic gastritis, and 5 patients had microscopic colitis. Many of these patients were on olmesartan for months or even years before onset of symptoms. Follow-up biopsy confirmed histologic improvement of the duodenum in 18 patients with sprue-like changes[2], demonstrating that CS can be induced by an autoimmune response to drugs and that morphologic pattern of injury is not necessarily indicative of underlying, specific etiology. As in our patient, 68% of these patients had HLA-DQ2, which is significantly higher than the prevalence reported in the general population of 25%-30%[2].

In conclusion, we report a clear case of an angiotensin-II inhibitor that caused villous blunting of the duodenum and gastrointestinal symptoms similar to those of celiac disease. Clinicians should be aware of the possibility of olmesartan-induced CS, with potential reversibility after discontinuation of the drug.

| 1. | Freeman HJ. Update on collagenous sprue. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:296-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rubio-Tapia A, Herman ML, Ludvigsson JF, Kelly DG, Mangan TF, Wu TT, Murray JA. Severe spruelike enteropathy associated with olmesartan. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:732-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 319] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Robert ME, Ament ME, Weinstein WM. The histologic spectrum and clinical outcome of refractory and unclassified sprue. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:676-687. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Goldstein NS. Non-gluten sensitivity-related small bowel villous flattening with increased intraepithelial lymphocytes: not all that flattens is celiac sprue. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:546-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewer Bian ZX S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor A E- Editor Ma S