Published online Oct 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i39.6679

Revised: August 3, 2013

Accepted: August 16, 2013

Published online: October 21, 2013

Processing time: 154 Days and 14.7 Hours

Lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage presents a common indication for hospitalization and account for over 300000 admissions per year in the United States. Multimodality imaging is often required to aid in localization of the hemorrhage prior to therapeutic intervention if endoscopic treatment fails. Imaging includes computer tomography angiography, red blood cell tagged scintigraphy and conventional angiography, with scintigraphy being the most sensitive followed by computer tomography angiography. Aberrant celio-mesenteric supply occurs in 2% of the population; however failure to identify this may result in failed endovascular therapy. Computer tomography angiography is sensitive for arterial hemorrhage and delineates the anatomy, allowing the treating physician to plan an endovascular approach. If at the time of conventional angiography, the active bleed is not visualized, but the site of bleeding has been identified on computer tomography angiography, provocative angiography can be utilized in order to stimulate bleeding and subsequent targeted treatment. We describe a case of lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage at the splenic flexure supplied by a celio-mesenteric branch in a patient and provocative angiography with tissue plasminogen activator utilized at the time of treatment to illicit the site of hemorrhage and subsequent treatment.

Core tip: In this article, the authors describe a case of lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage at the splenic flexure supplied by a celio-mesenteric branch in a patient and provocative angiography with tissue plasminogen activator utilized at the time of treatment to illicit the site of hemorrhage and subsequent treatment.

- Citation: Wu M, Klass D, Strovski E, Salh B, Liu D. Aberrant celio-mesenteric supply of the splenic flexure: Provoking a bleed. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(39): 6679-6682

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i39/6679.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i39.6679

Lower gastrointestinal (LGI) hemorrhages present a common indication for hospitalization and account for over 300000 admissions per year in the United States[1]. In the majority of these events, modern imaging and endoscopic techniques such as upper and/or lower endoscopy, tagged red blood cell scintigraphy, and visceral angiography can be used to localize the source of an acute hemorrhage[2]. Predictors on the ability to find a bleeding source include: (1) being visible on multidetector computed tomography angiography (CTA); (2) visible on tagged red blood cell scintigraphy; or (3) patient hemodynamic instability. Yet, in as many as 65% of cases, standard diagnostic evaluation will not identify the source of a bleed and these patients may present with recurrent bleeds from an obscure origin[3]. Modern radiologic studies require an active bleed and a minimal rate of bleeding in order to be detected. Since LGI hemorrhages can frequently resolve before imaging is performed, these studies may have difficulty in finding a source of the bleed[4]. If the bleeding vessel is not visualized angiographically, a provocative maneuver can be performed using heparin or tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) at the suspected site. This technique is based on the premise that these pharmacologic agents will incite an acute hemorrhage that can then be viewed angiographically. Once visualized, the source may be treated appropriately by embolization to occlude the vessel or by providing visual cues to assist a surgical procedure[5].

In this letter, we discuss the utility of a multidetector CTA scan in the setting of a LGI bleed that revealed the presence of an aberrant vessel supplying the splenic flexure responsible for the hemorrhage. With this information, we describe the use of provocative maneuvers to localize and successfully embolize the source of the bleed.

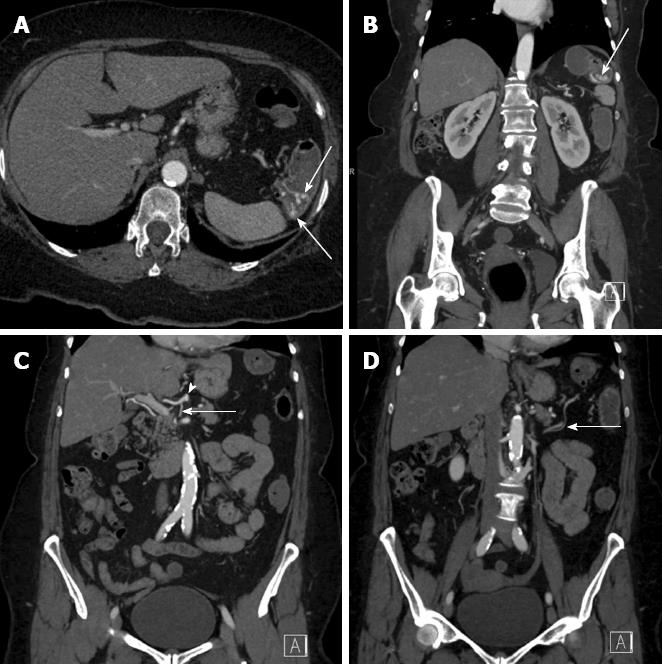

A 65-year-old female presented with the passage of bright red blood per rectum, the patient was not hemodynamically unstable (Blood pressure 110/60, pulse 78, saturation on room air 98%). Endoscopy was felt likely to be unhelpful due to the amount of blood passed per rectum and therefore decision was taken to proceed to CT. A subsequent arterial phase CT scan demonstrated an acute hemorrhage at the site of the splenic flexure (Figure 1A and B). Furthermore, a single aberrant vessel was seen arising from the proximal common hepatic artery (CHA) to supply the splenic flexure (Figure 1C and D). The patient was hemodynamically stable and transferred to the angiography suite for therapy.

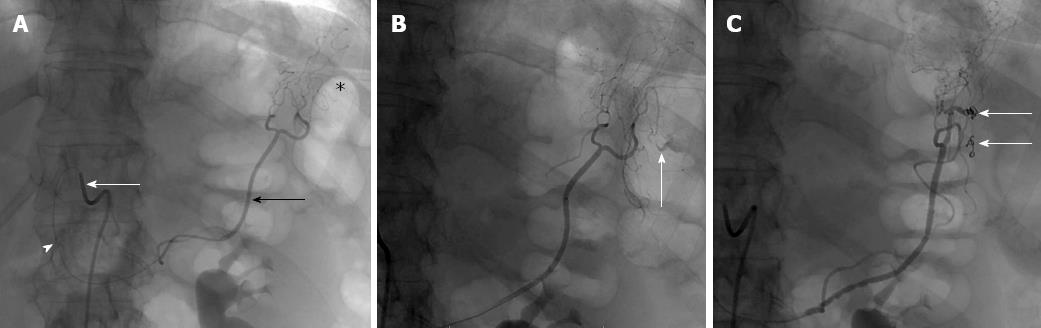

A celiac angiogram was initiated through the right common femoral artery using a 5-Fr sheath. Access was obtained via a Sim 1 catheter (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN) that extended to the celiac axis. As previously established on CTA, an aberrant celio-mesenteric branch extending from the CHA to the splenic flexure was confirmed. The Sim 1 catheter was engaged further and a Renegade STC catheter (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) was used to cannulate the vessel supplying the splenic flexure (Figure 2A and B).

Serial angiograms were performed in this area but no acute hemorrhage was visualized (Figure 2B). Decision was made to perform a tPa provocation test. Two milligram of tPA was dissolved in 10ccs of saline. One milligram of tPA was injected selectively through the catheter into the vessel supplying the splenic flexure. This resulted in brisk bleeding in the area of the splenic flexure from the aberrant vessel of the CHA (Figure 2C). At this point, the catheter was advanced and three 3 mm × 3.3 mm Vortex coils were injected in order to close the proximal and distal sites of the bleed. Further selective angiography did not demonstrate any acute contrast extravasation (Figure 2D).

The patient remained hemodynamically stable during the procedure and the blood pressure normalized at approximately 150/70 mmHg following embolization.

Patients with a gastrointestinal bleed of unknown origin present as a challenging population since typical investigations such as CT imaging, red blood cell scintigraphy and endoscopic procedures are unable to find a source to the bleed. Without a known source, these patients are usually subjected to increased risks from repeat bleeding events, invasive investigations, and blood transfusions[6]. Pharmacologic agents can be used to incite an acute, local bleed in order to visualize the source of the hemorrhage on CT scan. Although provocative angiography has yet to be a common diagnostic tool, the literature available through case reports and series has shown this to be an effective yet safe technique[2,4-8].

In this particular case, the inclusion of a CT angiogram in the setting of a GI bleed was invaluable in locating the source of the hemorrhage as the patient demonstrated aberrant vasculature from the CHA to the splenic flexure. The presence of variant vessels supplying the descending colon has been well documented and, although uncommon, would be important information in order to guide the management of a bleeding patient[9-11]. CTA provides excellent delineation of the arterial anatomy and is more sensitive than conventional angiography in identifying arterial bleeding[12].

The anastomosis between the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) at the splenic flexure is normally considered a watershed region with dual arterial supply from the SMA and IMA allowing collateral circulation. This region however is more susceptible to damage in ischemic disease.

In relatively rare cases, this point in the large bowel may receive blood supply from a celio-mesenteric branch. The anastomosis of atypical coeliac branches represents a rare case for consideration. Awareness of the possibility of embryological variants will assist in minimizing the risk of complications in angiographic procedures. Failure to identify this branch supplying the splenic flexure may lead to an incorrect assessment of the mesenteric vasculature, particularly at the time of angiography. It also provides comprehensive detail of the arterial anatomy and allows the radiologist to assess both access and potential target vessels for treatment.

We propose that in patients with a GI bleed that is difficult to locate, an arterial phase CT scan is a tool that can provide valuable information such as the ability to reveal variant vasculature that would have otherwise gone unnoticed. The protocol does not require oral contrast. Furthermore, if one is confident that there is a bleed but is unable to view angiographically, then a challenge with tPa or heparin may be a useful adjunctive diagnostic approach.

| 1. | Billingham RP. The conundrum of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:241-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bloomfeld RS, Smith TP, Schneider AM, Rockey DC. Provocative angiography in patients with gastrointestinal hemorrhage of obscure origin. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2807-2812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Zuckerman GR, Prakash C, Askin MP, Lewis BS. AGA technical review on the evaluation and management of occult and obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:201-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 339] [Cited by in RCA: 322] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kim CY, Suhocki PV, Miller MJ, Khan M, Janus G, Smith TP. Provocative mesenteric angiography for lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: results from a single-institution study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21:477-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Suhocki PV. Provocative Angiography for Obscure Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Techniques in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2003;5:121-126. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ryan JM, Key SM, Dumbleton SA, Smith TP. Nonlocalized lower gastrointestinal bleeding: provocative bleeding studies with intraarterial tPA, heparin, and tolazoline. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:1273-1277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Johnston C, Tuite D, Pritchard R, Reynolds J, McEniff N, Ryan JM. Use of provocative angiography to localize site in recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:1042-1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Malden ES, Hicks ME, Royal HD, Aliperti G, Allen BT, Picus D. Recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding: use of thrombolysis with anticoagulation in diagnosis. Radiology. 1998;207:147-151. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Yíldírím M, Celik HH, Yíldíz Z, Tatar I, Aldur MM. The middle colic artery originating from the coeliac trunk. Folia Morphol (Warsz). 2004;63:363-365. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Michels NA, Siddharth P, Kornblith PL, Parke WW. The variant blood supply to the descending colon, rectosigmoid and rectum based on 400 dissections. Its importance in regional resections: a review of medical literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 1965;8:251-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Manoharan B, Aland RC. Atypical coeliomesenteric anastomosis: The presence of an anomalous fourth coeliac trunk branch. Clin Anat. 2010;23:904-906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Laing CJ, Tobias T, Rosenblum DI, Banker WL, Tseng L, Tamarkin SW. Acute gastrointestinal bleeding: emerging role of multidetector CT angiography and review of current imaging techniques. Radiographics. 2007;27:1055-1070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewer Walter MA S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Ma S