INTRODUCTION

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is characterized by venous or arterial thrombosis or pregnancy morbidity, in the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL). A venous thrombosis is the most common presenting complication of APS[1]. Long-term anticoagulation therapy is recommended for the secondary prevention of thromboembolism.

Warfarin is a widely used anticoagulant prescribed for patients with venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, chronic atrial fibrillation, and prosthetic heart valves. Interindividual differences in drug responses, a narrow therapeutic range and the risk of bleeding render warfarin difficult to use clinically. During treatment with oral anticoagulants, the risk of severe bleeding has been estimated to be 0.6%-1.0% per treatment year[2,3]. In a retrospective study of hemorrhagic complications in 184 patients, gastrointestinal bleeding was the most common complication, and liver or splenic hemorrhage was identified in only 3 patients[4]. Only a few cases of liver hematomas have been reported in the literature following anticoagulant therapy[5]. We report a woman with primary APS who presented with a simultaneous intraparenchymal hemorrhagic complication in the liver and a subgaleal hematoma with anticoagulation treatment, without any risk factors of bleeding or an elevated international normalized ratio (INR). This type of condition has not been previously described.

CASE REPORT

An 18-year-old woman visited Dong-A University Hospital with swelling and tenderness of the left lower leg in March 2004. She had no past history of serious illness. Doppler ultrasonography (US) of her lower legs showed deep vein thromboses (DVT) in the left popliteal vein and the right common femoral vein. She received anticoagulation treatment with warfarin for 2 years. After 2 years, a follow-up US showed nearly complete improvement of the DVT, and anticoagulation therapy was stopped.

She returned four months later, in November 2006, with edema and tenderness of the right lower leg. US of her lower legs showed a chronic DVT in the right popliteal vein. We reexamined her for other conditions leading to a hypercoagulable state. The clinical lab values were as follows: white blood cell count (WBC) 4570/mm3, segmental neutrophils 29%, hemoglobin (Hb) 11.9 g/dL, platelets (PLT) 91000/mm3, prothrombin time (PT) 13.9 s, INR 1.23 and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) 31.3 s. Tests for antinuclear antibodies were positive (at 1:40 dilution), and the particular types of immunofluorescence pattern were negative. An anti-double-stranded DNA antibody enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay test was moderately positive (326.7 WHO unit/mL). Anti-Smith antibody and anti-ribonucleoprotein antibody test were negative. Immunoglobulin (Ig)G anti-β2-glycoprotein I (anti-β2 GPI) was positive (98.8 GPL), and IgM anti-β2-GPI was positive (95.5 GPL). IgG anticardiolipin antibodies (aCL) were highly positive (95.6 GPL), and IgM aCL was positive (37.9 MPL). Lupus anticoagulant testing (diluted russell viper venom test, DRVVT) was positive (185.5 s). The patient was diagnosed with primary APS according to the revised Sapporo criteria for APS diagnosis[6,7], and oral anticoagulation treatment was initiated.

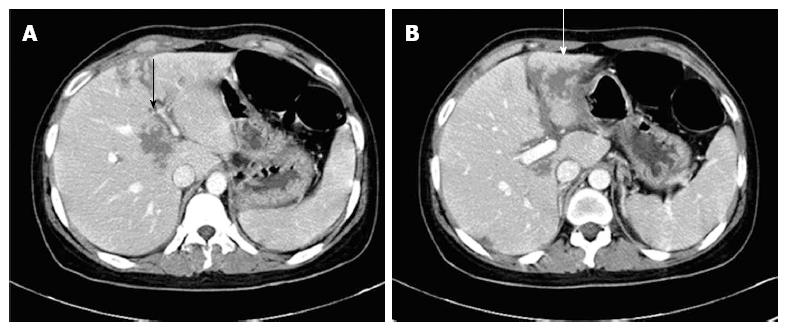

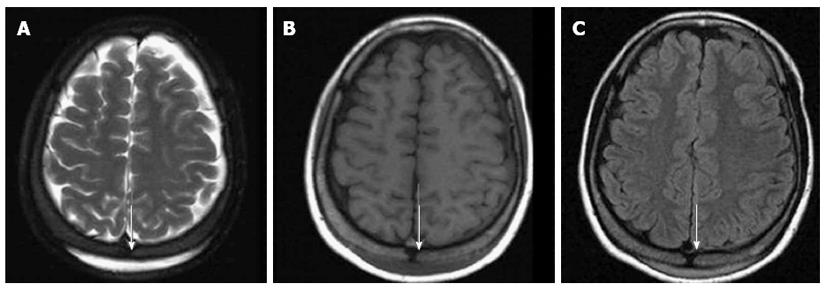

After forty months of anticoagulation therapy, the patient was admitted in April 2010 with epigastric pain, headache, fever and chills. On physical examination, she had epigastric tenderness and body temperature of 38.2 °C. The laboratory findings were: WBC 17111/mm3, segmental neutrophils 82.9%, Hb 9.7 g/dL, PLT 136000/mm3, C-reactive protein (CRP) 8.38 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase 211 I/U, PT INR 1.82 and aPTT 31.4 s. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed multiple low attenuated lesions without peripheral enhancement and perilesional edema of the liver on contrast-enhanced image (Figure 1). A brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a crescentic high signal in the posterior parietal scalp on the T2 weighted image, a low signal on the T1 weighted image and mild enhancement on the contrast-enhanced scan images (Figure 2). We suspected intraparenchymal hemorrhage in the liver and a subgaleal hematoma in the posterior parietal scalp because of bleeding complications from anticoagulation. We stopped the warfarin treatment and administered antibiotics because there was the potential for an infected intrahepatic hemorrhage. After 2 wk of supportive care, a follow-up US on day 16 showed resolution of a previous hepatic lesion. We decided to restart warfarin because of her recurrent thrombotic episodes.

Figure 1 Intraparenchymal hemorrhage in the liver (arrows).

An abdominal computed tomography showed multiple low attenuated lesions without peripheral enhancement (A) and perilesional edema of the liver on the contrast-enhanced image (B).

Figure 2 Subgaleal hematoma at the posterior parietal scalp (arrows).

A brain magnetic resonance imaging showed a crescentic high signal in the posterior parietal scalp on the T2 weighted image (A), a low signal on the T1 weighted image (B) and mild enhancement on the contrast-enhanced image (C).

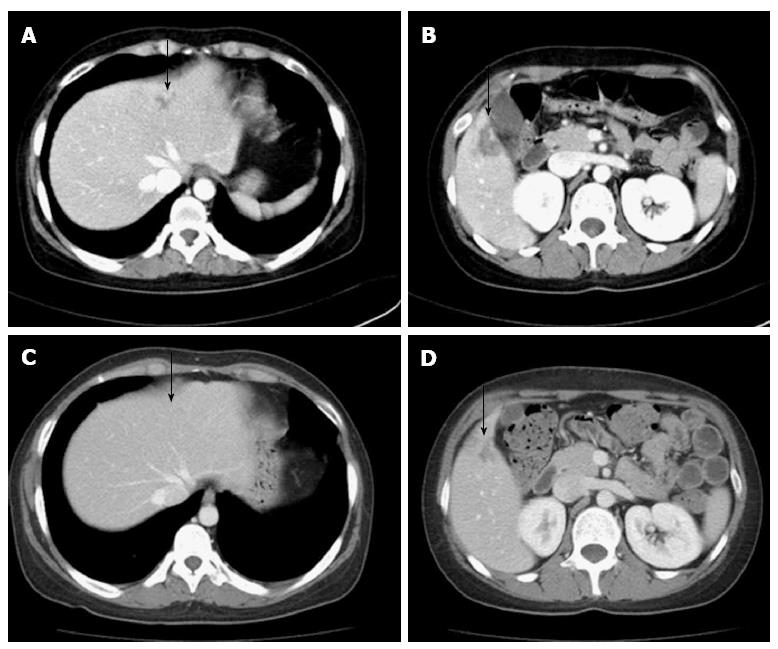

She was readmitted in June 2010 with right flank pain. On physical examination, she had abdominal tenderness in the right upper quadrant and her body temperature was normal. The WBC was 13250/mm3, the segmental neutrophils were 80.8%, the Hb was 10.2 g/dL and the PLT were 88000/mm3. The CRP was 7.93 mg/dL. The PT INR was 1.53, and the aPTT was 29.8 s. Liver and kidney function tests were unremarkable. An abdominal CT showed a low attenuated lesion in the S2/4 and S5 segments of the liver on the contrast-enhanced image (Figure 3A and B). We diagnosed the patient with intraparenchymal hemorrhage of the liver from the anticoagulation therapy and stopped warfarin treatment. Follow-up CT scanning on day 17 showed nearly complete improvement of intraparenchymal hemorrhage in the S2/4 and S5 segments of the liver (Figure 3C and D). After 1 mo, a follow-up US showed the previous intrahepatic lesions were completely resolved. We decided to initiate clopidogrel and hydroxychloroquine instead of warfarin. Subsequently, the patient has not developed recurrent thrombotic episodes or bleeding complications.

Figure 3 Recurrent and nearly complete resolution intraparenchymal hemorrhage in the liver (arrows).

A, B: An abdominal computed tomography showed a low attenuated lesion (arrow) in the S2/4 (A) and S5 segments (B) of the liver on the contrast-enhanced image; C, D: An abdominal computed tomography showed resolution of the parenchymal hemorrhage in S2/4 (C) and the healing process in S5 (D) of the liver.

DISCUSSION

APS is characterized by the occurrence of venous or arterial thromboses or by specific pregnancy morbidity in the presence of laboratory evidence of aPL. According to the revised Sapporo criteria[6,7], definite APS is considered if at least one of the clinical criteria and at least one of the laboratory criteria are satisfied. APS occurs either as a primary or secondary condition in the setting of an underlying disease, usually systemic lupus erythematosus. In the largest prospective cohort study of patients with APS, venous thromboembolism was the most common presenting complication, including DVT (31.7%), pulmonary embolism (9.0%), and superficial thrombophlebitis (9.1%)[1]. Warfarin is the standard of care for the chronic management of patients with APS who are not pregnant.

Warfarin is an oral anticoagulant used in a variety of clinical settings. The anticoagulant effect of warfarin is mediated through inhibition of the vitamin K-dependent gamma-carboxylation of coagulation factors II, VII, and X. Warfarin is among the top 10 drugs with the largest number of serious adverse event reports submitted to the United States Food and Drug Administration, because it has a high incidence of adverse effects as well as variable interactions with diet or medications through a mechanism of altered platelet function, altered vitamin K synthesis in the gastrointestinal tract and interference with vitamin K metabolism[8-11]. In a prospective observational study, life-threatening bleeding occurred in 32 of 1999 patients. The gastrointestinal tract was the most common site, with bleeding occurring in 21 (66%) of the 32 patients[12]. In another study of hemorrhagic complications in 184 patients, gastrointestinal bleeding was the most common complication and unusual hemoperitoneum and/or soft tissue bleeding were reported[4]. Liver hemorrhage following anticoagulation therapy has been rarely reported in the literature[5,13-15]. It is sometimes difficult to distinguish hepatic hemorrhage from a liver abscess. Liver abscesses appear as low attenuated lesions with peripheral enhancement or perilesional edema[16,17]. We diagnosed a patient with an intrahepatic hemorrhage because these characteristics were not observed in our patient. We discussed the possibility of a microaneurysm in the liver and brain with radiology specialists who said that it was very unlikely.

There are many risk factors associated with bleeding complications following the use of vitamin K antagonist. These risk factor have been associated with a significantly increased risk of bleeding in one or more multivariate analyses: old age, diabetes mellitus, the presence of malignancy, hypertension, acute or chronic alcoholism, liver disease, severe chronic kidney disease, elevated creatinine, anemia, the presence of bleeding lesions or episodes, a bleeding disorder, concomitant use of aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiplatelet agents, antibiotics, amiodarone, statins or fibrates, and instability of the INR (INR > 3.0, pre-treatment INR > 1.2)[18,19].

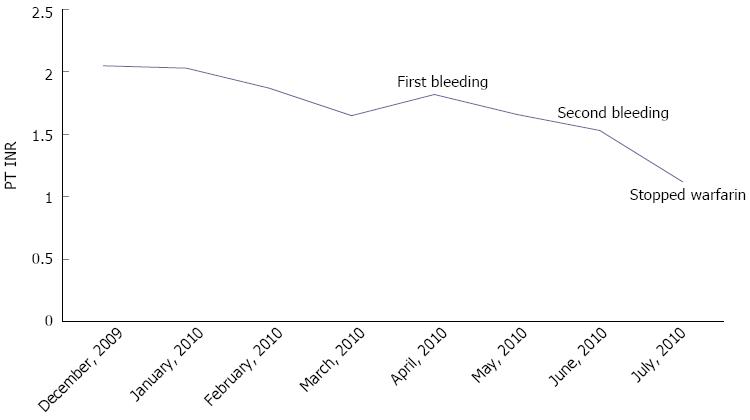

In previously reported spontaneous liver hemorrhages, Erichsen et al[14] addressed the severe drug interaction between warfarin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Dizadji et al[13] and Roberts et al[15] showed the two risk factors of old age and high INR at the time of admission. Behranwala et al[5] suggested multiple risk factors, including; old age, hypertension, instability of INR control, and drug interactions with statins and omeprazole. Our patient had a simultaneous intraparenchymal hemorrhage in the liver and subgaleal hematoma despite the absence of risk factors for bleeding and a therapeutic range of warfarin with a PT INR of 1.53 (Figure 4). This type of case has not been previously reported.

Figure 4 Extended follow-up data for the prothrombin time international normalized ratio.

PT INR: Prothrombin time international normalized ratio.

One study suggested risk factors that could be used in estimating the probability of major bleeding in outpatients treated with warfarin. The risk factors include the following; age ≥ 65 years, history of stroke, history of gastrointestinal bleeding, and one or more the following (recent myocardial infarction, hematocrit < 30%, serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL, and diabetes mellitus[20]. The cumulative incidence of major bleeding at 48 mo in the low (no risk factor), intermediate (1 to 2), and high (3 or more) risk groups was 3%, 12% and 53% respectively. Our patient belonged to the low risk group with a cumulative incidence of only 3%. Some recent reports showed that APS could be correlated to a transient hemorrhagic event without anticoagulation therapy[21,22]. Lupus anticoagulant-hypoprothrombinemia syndrome is a rare clinical entity that can occur in association with systemic lupus erythematosus. It is characterized by prolongation of the coagulation test that is not corrected by normal fresh plasma because of non-neutralizing antibodies against Factor II. Our patient did not have this abnormal laboratory finding.

There are very few randomized studies comparing the treatment options for patients with an elevated INR and/or bleeding complications following the use of warfarin. If significant or life-threatening bleeding occurs, rapid reversal of excessive anticoagulation should be undertaken at any degree of anticoagulation[23-26]. Warfarin should be stopped, and 10 mg of vitamin K should be administered by a slow intravenous infusion, supplemented by fresh frozen plasma for less urgent situations. For more urgent situations, recombinant human factor VIIa or prothrombin complex concentrate may be used. If needed, angiography may help with embolization in cases of severe major bleeding. In the majority of cases, bleeding is improved by stopping warfarin and conservative care. Restarting of warfarin is not recommended, and changing the drug used for maintaining long-term anticoagulation is suggested[5].

In studies of the bleeding risk during antithrombotic therapy, the odds ratio is generally lower for clopidogrel than warfarin, and we decided to start clopidogrel instead of warfarin[27,28]. We added hydroxychloroquine because limited data showed that it might be useful for thrombosis in patients with APS although there were no randomized controlled trials[29,30]. After starting clopidogrel and hydroxychloroquine, our patients did not experience additional bleeding complications or recurrent thromboses.

Our patient had a simultaneous intrahepatic hemorrhage and a subgaleal hematoma despite the absence of risk factors and a therapeutic range of warfarin. This is the first case with simultaneous bleeding in the liver and brain in an APS patient treated with warfarin.

Patients with intrahepatic bleeding might experience right upper quadrant or epigastric pain and pain that radiates into the shoulder or flank. Fever might develop when an infection accompanies the intrahepatic hemorrhage. If a patient experience pain and/or fever during anticoagulation therapy, we should consider the possibility of abdominal bleeding such as an intrahepatic hemorrhage in any patient receiving oral anticoagulants, even though this circumstance remains unlikely. CT or US should be adopted for early diagnosis.