CASE REPORT

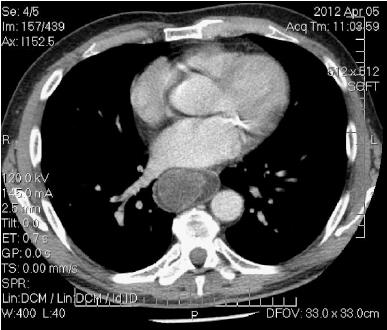

A 60-year-old man, with a negative medical history, was admitted to another hospital eight months ago for anemia and underwent colonoscopy (findings: negative), gastroscopy (findings: esophageal neoformation of the lower third of the esophagus), and computed tomography (CT) (findings: submucosal esophageal neoformation capturing contrast medium, extending from the cervical to the cardiac esophagus). After transfusion therapy, the patient refused any surgical treatment. He enjoyed good health until another episode of anemia occurred (hemoglobin 8.6 g/dL) and he presented at our facility. The patient underwent a gastroscopy (findings: esophageal stenosis for submucosal neoformation arising from the cervical esophagus, occupying approximately 50% of the esophageal lumen, with mucosal integrity, and protrusion of a neoformation with erosion of its apex into the gastric cavity). He also underwent a contrast CT (findings: bulky neoformation jutting into the esophageal lumen extending from the cervical to the distal esophagus with a maximum diameter of 35 mm × 46 mm, associated with increased esophageal diameter) (Figure 1). The patient then underwent an endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) (findings: thickening of the esophageal wall due to a solid, hypoechoic, neoformation, with hyperechoic areas and a vascular network, originating from the submucosa of the cervical esophagus, which affected the esophagus from cardiac portion to the upper esophageal sphincter) (Figure 2). At the conclusion of the procedure, during the extraction of the echoendoscope, the patient began retching and regurgitated the polyp, without experiencing respiratory distress (Figure 3). The patient was taken to the operating room and, under general anesthesia, a gastroscopy was repeated. It revealed that the origin of the polyp was not at the upper esophageal sphincter (UES), as previously diagnosed by CT, EUS, and the first gastroscopy; rather, it originated in the hypopharynx below the left arytenoid cartilage, with a stalk of about 3 cm in length. The patient underwent a left cervicotomy and polyp dissection via a pharyngotomy. The removal of the polyp was performed with a stapler (Endogia 45, Ethicon®). At the conclusion of the procedure, a dual lumen nasogastric tube was placed. On the seventh postoperative day the patient underwent a radiological evaluation with water-soluble contrast medium, which imaged good transit in the absence of extraluminal spillage. The patient began a semi-liquid diet and was discharged on the 10th postoperative day. A gastroscopic evaluation 45 d postoperatively was normal.

Figure 1 Computed tomography (mediastinal window setting) shows bulky neoformation jutting into the esophageal lumen.

Figure 2 Endoscopic ultrasound shows a solid, hypoechoic, neoformation, with hyperechoic areas and a vascular network.

Figure 3 Giant, regurgitated hypopharyngeal polyp.

DISCUSSION

Benign esophageal/hypopharyngeal tumors are rare and represent less than 1% of esophageal/hypopharyngeal neoplasms, e.g., Moersch and Harrington[3] discovered 44 (0.59%) benign esophageal tumors in 7459 consecutive autopsies at the Mayo Clinic. Most of these tumors are intramural, represented by leiomyomas, neurofibromas, and hemangiomas; the intraluminal lesions are represented by fibrolipomas, fibromixomas, hamartomas, fibromas, and lipomas[4]. These tumors are globally ranked by the World Health Organization as fibrovascular polyps. Histologically, giant esophageal polyps are covered by squamous epithelium with a fibrovascular axis, consisting of adipose and connective tissue to varying degrees, and a well-developed vascular network. Despite the rarity of these tumors, interest in giant esophageal polyps derives from their degree of growth (characterized by slow growth into the esophageal lumen) and their mobility. In fact, if regurgitation occurs, they can ascend into the oral cavity and be aspirated into the airways, with potentially lethal consequences. They are more frequent in males (male:female ratio = 3:1)[4], and are usually diagnosed in the sixth or seventh decade of life; however, fibrovascular polyps have been reported in childhood[5]. About 85% are located in the upper third of the esophagus, close to the UES, and originate as small mucosal tumors, extending into the esophageal lumen due to the constant downward thrust by food ingestion and peristalsis. In the present case, the polyp was attached in an unusual site, at the level of the left anterolateral hypopharyngeal wall immediately below the ipsilateral arytenoid cartilage, with dimensions of 18 cm × 5.4 cm × 4 cm. Fibrovascular polyps usually occur as solitary lesions; however, some authors have reported synchronous polyps[6]. Due to progressive tumor growth, most patients report progressive dysphagia, initially with solid food and then with liquids. The second most frequent symptom is the regurgitation of the polyp into the hypopharynx or oral cavity with the risk of aspiration into the airways, resulting in asphyxia[7-10]. In a small percentage of patients, aspiration of the polyp may be the presenting symptom. Other symptoms include pharyngeal globus, weight loss, odynophagia, pharyngodynia, vomiting, abdominal pain, gastroesophageal reflux, hiccups, melena, and anemia[4,11]. The latter two symptoms are a result of ulceration of the apical part of the polyps due to gastric acidity or reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus. Malignant degeneration of these polyps is rare.

Fibrovascular polyps can be detected by either a barium esophagogram or gastroscopy. The former may reveal a dilated esophagus, with a gross intraluminal defect usually arising in proximity to the UES. However the examination may be entirely negative especially if the polyp remains in contact with the esophageal wall. The diagnosis, however, by gastroscopy, sometimes may be difficult or impossible because the fibrovascular polyp can completely or partially occupy the esophageal lumen, move against the esophageal wall and thus present a similar appearance to the mucosa. Diagnostic suspicion can be confirmed with a rear view, because if the terminal part of the polyp protrudes into the gastric cavity, it may image as a “clapper of a bell”; thus illustrating the circumferential space between the two walls. EUS may be useful for diagnosis because it clearly highlights the fibrovascular axis of the polyp, the echogenic aspect of adipose tissue, and the presence of anechoic areas due to its vascular network. Finally, this imaging procedure can help in a diagnosis via a needle aspiration. CT and magnetic resonance (MR) can be useful in confirming diagnostic suspicion and in deciding the proper surgical approach. In particular, MR with axial coronal and sagittal scans, allows a precise identification of the stalk, an essential requirement for proper treatment. Despite a careful diagnostic process, fibrovascular polyps can be confused with intramural lesions; thus, identification of the stalk can be difficult and incorrect. In a review by Caceres et al[2], 22% of barium esophagograms and 33% of gastroscopies yielded false negative results. Due to the potentially disastrous complications, removal of benign esophageal and hypopharyngeal polyps is strongly recommended. This can be achieved using a transoral, transcervical, transthoracic, or endoscopic approach, depending on the location and size of the polyp.

Two field approaches (abdominal and cervical) have also been described in patients with unusually large polyps[12]. It is clear that the correct diagnosis is essential to avoid unnecessary intervention and especially to choose the type of the intervention: surgical or endoscopic. For example, Oh et al[13] reported some difficulty in removing a cervical esophageal fibrovascular polyp through a right thoracotomy. Most polyps are surgically removed, especially those with a large, vascularized stalk; however, it has been performed endoscopically by dissection of the peduncle by ligature, electrocoagulation, or laser[14,15]. Generally, the removal of the polyp is curative and recurrence after resection is rare; however, some authors have reported a recurrence[16,17].

In conclusion, giant esophageal polyps are extremely rare, benign tumors, whose removal is recommended because of the possibility of fatal consequences, bleeding and malignant transformation (rare). An adequate preoperative evaluation to identify the correct origin of the stalk is mandatory for a successful endoscopic or surgical treatment. In addition to the removal of the giant polyp, all mucosal redundancy must be evaluated and possibly removed to avoid recurrences, which are rare but possible.