Published online Sep 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i35.5848

Revised: July 26, 2013

Accepted: August 4, 2013

Published online: September 21, 2013

Processing time: 156 Days and 16 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the outcomes of patients who underwent laparoscopic repair of intra-thoracic gastric volvulus (IGV) and to assess the preoperative work-up.

METHODS: A retrospective review of a prospectively collected database of patient medical records identified 14 patients who underwent a laparoscopic repair of IGV. The procedure included reduction of the stomach into the abdomen, total sac excision, reinforced hiatoplasty with mesh and construction of a partial fundoplication. All perioperative data, operative details and complications were recorded. All patients had at least 6 mo of follow-up.

RESULTS: There were 4 male and 10 female patients. The mean age and the mean body mass index were 66 years and 28.7 kg/m2, respectively. All patients presented with epigastric discomfort and early satiety. There was no mortality, and none of the cases were converted to an open procedure. The mean operative time was 235 min, and the mean length of hospitalization was 2 d. There were no intraoperative complications. Four minor complications occurred in 3 patients including pleural effusion, subcutaneous emphysema, dysphagia and delayed gastric emptying. All minor complications resolved spontaneously without any intervention. During the mean follow-up of 29 mo, one patient had a radiological wrap herniation without volvulus. She remains symptom free with daily medication.

CONCLUSION: The laparoscopic management of IGV is a safe but technically demanding procedure. The best outcomes can be achieved in centers with extensive experience in minimally invasive esophageal surgery.

Core tip: Migration of the whole stomach in to the chest cavity by rotating its longitudinal or transverse axis, namely “intra-thoracic gastric volvulus’’, is a very rare type of giant hiatal hernias and is associated with catastrophic complications. Laparoscopic repair of this rare condition is the most technically demanding procedure among the benign foregut surgeries. With careful attention the details, such as total excision of the hernia sac, provision of an adequate esophageal length with full mobilization of the esophagus, tensionless hiatoplasty, and a floppy fundoplication, long-term success is possible

- Citation: Toydemir T, Çipe G, Karatepe O, Yerdel MA. Laparoscopic management of totally intra-thoracic stomach with chronic volvulus. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(35): 5848-5854

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i35/5848.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i35.5848

It is difficult to identify the true incidence of hiatal hernia because of the absence of symptoms in a large number of patients. Hiatal hernia is most commonly associated with gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD), and GERD affects millions of people worldwide[1]. Ninety-five percent of hiatal hernias are the small sliding type (type I) and are not associated with life threatening complications. The remaining 5% are classified as paraesophageal and mixed types (types II and III, respectively) both of which are known as giant hiatal hernias.

Landmark articles on giant hernias were published by Skinner et al[2] in 1962 and Hill[3] in 1973. They reported mortality rates exceeding 27% due to catastrophic complications of paraesophageal hernia (PEH) such as obstruction, strangulation, perforation and bleeding. Although still controversial, many surgeons recommend elective surgical repair even in elderly asymptomatic patients with PEH[4].

After Cuschieri et al[5] performed the first laparoscopic PEH repair, many surgeons reported successful results with less than 1% mortality[6,7]. All studies have shown that laparoscopic repair of giant hiatal hernias is a safe but technically demanding procedure. Because of the rarity of this disease and the lack of randomized trials comparing different surgical approaches, controversy exists regarding which surgical approach should be preferred. Choices regarding the type of surgical procedure include trans-abdominal vs trans-thoracic, open vs laparoscopic, hiatal closure with primary suture vs the use of meshes and whether fundoplication is necessary[8,9].

Many previous publications addressed the management of PEH, but there is a distinct subgroup of patients who represent the end stage of all types, which occurs when the whole stomach migrates into the thorax by rotating 180 degrees around its longitudinal or transverse axis, namely “intra-thoracic gastric volvulus (IGV)’’. Surgical repair of this rare disorder is most likely the most technically difficult procedure among the benign foregut diseases, even for experienced foregut surgeons. The present article focuses on this subgroup of patients who have IGV.

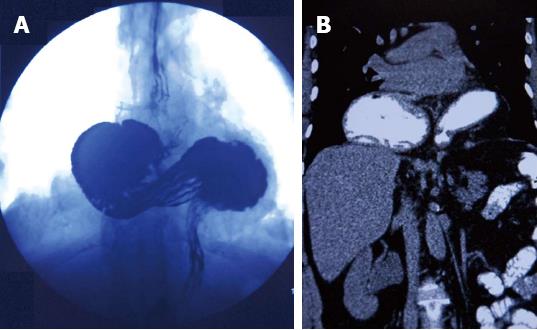

The study was conducted at our anti-reflux therapy center, which is a specialized tertiary referral center for the diagnosis and treatment of GERD. A retrospective review of a prospectively collected database of patient medical records identified 14 patients who underwent laparoscopic repair for a totally intra-thoracic stomach with chronic volvulus. IGV was defined as transmigration of the whole stomach into the thorax by a 180 degree around its longitudinal or transverse axis (Figure 1). Surgical consent was obtained from all patients after detailed information was given by a senior surgeon. The preoperative evaluation included an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, thoraco-abdominal computed tomography (CT) and a barium esophagram. We do not perform a routine 24-h pH study or manometry as the results do not change our treatment strategy in IGV cases. Pulmonary function testing was performed in patients with pulmonary symptoms, such as shortness of breath, to determine whether breathing problems were due to restriction of the lung by an intra-thoracic stomach or to intrinsic lung disease.

All patients were admitted on the day of the surgery and underwent a laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair procedure after an overnight fast. Patients received prophylaxis by subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin administered routinely during the induction of anesthesia in addition to compression stockings.

Patients were placed in the modified lithotomy position with the surgeon between the legs and the assistant on the left side. The first 10-mm optic port was placed using the open Hasson technique in the upper midline approximately one third of the way from the umbilicus to xiphoid. An additional three 10-mm and two 5-mm trocars were placed in the upper abdomen after a pneumoperitoneum was established to a pressure of 13-15 mmHg. Unlike patients who undergo an antireflux surgery, trocar placement was higher in the abdomen and was very similar to the placement in obese GERD patients we previously reported[10].

Following liver retraction, the hiatal hernia was examined. Then the operating room table was placed in reverse Trendelenburg to allow an easier reduction. The herniated stomach was reduced into the abdomen as much as possible with atraumatic graspers in a hand-over-hand fashion. The dissection was started by dividing the gastro-hepatic ligament and exposing of the right crus. If a dominant left hepatic artery larger than 2 mm was seen, the dissection was started just above the vessel. There was no attempt to dissect the hernia sac or to find the esophagus at this stage. The hernia sac was identified at the junction of the left crus and stomach. Finding a fine areolar plane between the sac and surrounding mediastinal tissues was a landmark following the division of the hernia sac. Care was taken to identify the vagal nerves and pleura to avoid any injury during the dissection of the mediastinum. Full division and removal of the sac was performed in all patients.

Following the sac removal, a circumferential dissection of the esophagus to the level of the inferior pulmonary veins was performed to achieve adequate intra-abdominal esophagus length. The final assessment of the esophageal length was conducted after careful dissection of the fat pad of the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) with the operating table in a level position and with a 6-8 mmHg pneumoperitoneum. Collis gastroplasty (CP) was not routinely performed prior to fundoplication.

Once the esophageal dissection was completed, a crural repair with silk sutures was performed. Care was taken to avoid any tension over the crura during the repair, and we aimed to secure the integrity of the muscle. Reinforced hiatoplasty with prosthetic grafts was routinely performed. A U-shaped monofilament polypropylene graft (Prolene; Ethicon, Ltd.) was used for the reinforced hiatoplasty. The mesh was fixed to the diaphragm by a laparoscopic tacker. A fundoplication was performed during the procedure to avoid postoperative acid reflux. A partial posterior fundoplication, namely “Toupet fundoplication”, was the procedure of choice. We believe a better fixation of the gastric fundus is achieved with more sutures to the esophagus and crura using the Toupet procedure. Our partial fundoplication technique was standardized and reported elsewhere[11]. Briefly, the right side of the wrap was fixed to the esophagus using two silk sutures. The left part of the wrap was sutured to the anterior side of the esophagus by two or three sutures, and a single suture was used to fix the upper side of the wrap to the upper edge of the hiatus. There was no attempt to divide the short gastric vessels as the gastric fundus is too mobile due to long-term herniation.

The length of postoperative observation in the intensive care unit depended on patient co-morbidities and the operation length. All patients were discharged on the second postoperative day unless problems occurred. Patients received liquids on the first postoperative day, after an esophagram was obtained. All patients were seen at intervals of 1 wk and 2 mo after surgery and yearly thereafter. A barium esophagram was performed during annual follow-up evaluations.

Fourteen consecutive patients underwent a laparoscopic repair of IGV. There was no mortality, and none of the cases were converted to an open procedure. The duration of follow-up was 29.4 mo. There were 4 male and 10 female patients. The mean age and mean body mass index were 66.7 years and 28.7 kg/m2, respectively. All patients presented with epigastric discomfort and early satiety. Only 2 patients had additional reflux symptoms of heartburn and 2 had shortness of breath. The demographic characteristics of the patients are outlined in the Table 1.

| Age, yr (range) | 66.7 ± 4.7 (61-76) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 4 (28.6) |

| Female | 10 (71.4) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.7 ± 7.6 |

| Symptoms | |

| Early satiety | 14 (100) |

| Postprandial discomfort | 14 (100) |

| Shortness of breath | 2 (14.2) |

| Heartburn | 2 (14.2) |

| Duration of operation (min) | 234.9 ± 59.2 |

| Day of discharge (d) | 2.6 ± 1.4 |

| Minor complication | 4 (28.6) |

| Recurrence | 1 (7.1) |

| Mean follow-up (mo) | 29.4 ± 19 |

The mean operative time was 234.9 min, and the mean length of hospitalization was 2.6 d. There were no intraoperative complications. Four minor complications occurred in three patients. One patient had pleural effusion and subcutaneous emphysema that spontaneously resolved within 2 wk. One patient had postoperative dysphagia that resolved within 6 wk without any intervention. One patient had postoperative delayed gastric empting that began in the first postoperative week. She was treated with medical therapy and her complaints resolved within 6 mo. One patient presented with recurrent heartburn 6 mo postoperatively, and a wrap herniation was diagnosed with gastroscopy and barium swallow studies. She remains symptom free with daily proton pump inhibitor usage.

An IGV is an uncommon entity and it occurs when the entire stomach migrates into the thorax through a giant hiatal defect by rotating around its longitudinal or transverse axis. Whether this rare condition is an extension of a PEH or an evolution of a longstanding sliding hernia is subject to controversy and is beyond the scope of this article. IGV is the end stage of all hiatal hernia types before catastrophic complications occur.

The clinical features of giant hiatal hernias are nonspecific and the majority of patients are asymptomatic. Dysphagia, heartburn, postprandial discomfort and chest pain are the most common presenting symptoms[12]. Patients presenting with chest pain usually undergo a cardiac work-up and a PEH is incidentally found in chest scans. Patients with IGV are usually symptomatic, and in our study all patients presented with early satiety and postprandial discomfort.

We usually start with a gastroscopy in the preoperative work-up. In addition to detecting esophagitis and/or Barrett metaplasia, an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy can reveal other concomitant gastric neoplasias as the majority of patients are over 65 years old with non-specific symptoms. Unfortunately, total gastroscopy cannot be performed in most patients with IGV even under general anesthesia. Following gastroscopy, we obtain a radiographic evaluation with a barium swallow study and thoraco-abdominal CT. We think the barium swallow is very useful in identifying the presence and the type of volvulus, the location of the GEJ and in assessing the length of the esophagus. CT imaging is useful to determine possible associated organ herniation and to rule out of diaphragmatic hernia. Preoperative evaluation of patients with a pH meter and manometry is controversial. Fuller and co-workers reported 60% of patients with a giant hiatal hernia had pathological acid reflux despite the absence of typical symptoms[13]. Schieman et al[14] recommend routine pH meter and manometry to reveal possible concomitant reflux. We do not perform routine pH meter or manometry in our clinical practice as the results do not change our treatment strategy.

In 2013, there remains no consensus among foregut surgeons regarding the optimal surgical approach to giant hiatal hernias. The approaches include trans-abdominal vs trans-thoracic procedures, open vs laparoscopic procedures, hiatal closure with primary suture vs the use of meshes, fundoplication, gastroplasty and total sac excision. Because of the rarity of this disease only small series and case reports exist in the literature (Table 2). As we had extensive experience in more than 1000 anti-reflux operations, a laparoscopic approach was the procedure of choice in our series. Some surgeons advocate the transthoracic approach especially in emergency cases[24]. The improved ability to separate adhesions between the hernia sac and pleura is the main advantage of transthoracic repair. In recent years, successful thoracoscopic repair of intrathoracic stomach has started to appear in the literature[25]. The surgeon’s experience seems to be the most important consideration in choosing the procedure.

| Ref. | n | Presentation | Follow-up | Mesh | Fundoplication procedure | Outcome |

| Inaba et al[15] | 1 | Upper abdominal pain | 4 yr | PTFE | Toupet | Cure |

| Gökcel et al[16] | 7 | - | 5 mo | PTFE | Anterior semi fundoplication | One recurrence without volvulus |

| Salameh et al[17] | 1 | Chest discomfort, inability to belch | 1 yr | None | Nissen | Cure |

| Malik et al[18] | 2 | Epigastric pain, vomiting, bloating | 1 yr | None | Nissen | Cure (PEG tube was placed in one patient and removed after 6 mo) |

| Rathore et al[19] | 1 | Chest pain, shortness of breath | 1 yr | None | None | Cure |

| Golash[20] | 1 | Epigastric pain, inability to eat | 6 mo | Polypropylene | Nissen+ anterior gastropexy | Cure |

| Iannelli et al[21] | 1 | Epigastric pain, vomiting | 18 mo | - | Nissen | Cure |

| Krahanbuhl et al[22] | 3 | Epigastric pain, vomiting | 21 mo | None | Nissen + anterior gastropexy | One recurrence with volvulus |

| Katkhoudan et al[23] | 8 | Epigastric pain, early satiety | 16 mo | None | Nissen | One recurrence without volvulus |

The debate over total excision of the hernia sac is the least controversial issue. Many surgeons believe total excision of the sac eliminates the tension on the GEJ and minimizes the risk of recurrence. Edye et al[26] addressed this issue and reported 20% early period recurrence in patients without sac excision. Although the total excision of the sac decreases the recurrence rates, some surgeons prefer to leave the distal part of the sac as a fail-safe measure to counter difficulties in dissecting nearby pleura and vagal nerves. We believe total excision is the critical step of the operation in patients with IGV, as reducing the volvulus can only be achieved by total excision. It may be very difficult when the vagus is partly adherent to the sac, especially anteriorly, and one of our patients had postoperative delayed gastric emptying after a demanding dissection. Her complaints spontaneously resolved after 6 mo, and we believe vagal injuries may not result in long-term clinical sequelae.

Short esophagus was first described in 1957[27], and since then its pathophysiology, importance and management have remained a subject of clinical debate. Hypothetically, the inflammation of the posterior mediastinum due to the intra-thoracic stomach results in adhesion that causes esophageal shortening. The associated acid reflux can lead to chronic inflammation and fibrosis in the connective tissues that finally results in esophageal shortening. Despite the various attempts, specific criteria allowing surgeons to preoperatively identify short esophagus and to determine which patients will need a CP do not exist[28,29]. Although CP has become a more commonly used procedure in the past decade[30], some surgeons believe that there is no need to perform CP with an adequate esophageal dissection[31]. If a 2.5-3 cm intra-abdominal esophagus can be achieved by mediastinal dissection, there is no need to perform a Collis procedure. There is a tendency to overestimate the esophageal length during a laparoscopy. The pneumoperitoneum elevates the diaphragm and misleads surgeons. Surgeons should keep in mind that these maneuvers can lead to an overestimate of intra-abdominal esophageal length. A CP was not needed in our experience. In one patient, we suspected an esophageal shortening based on a preoperative upper intestinal series. After mobilization of the esophagus and careful dissection of the fat pad over the GEJ, we thought we had achieved an adequate esophageal length. Unfortunately, she was the patient who presented with recurrence.

The use of prosthetic grafts for a reinforced hiatoplasty is another controversial issue in the treatment of giant hiatal hernias. The main point of controversy includes what shape, size and type of mesh should be used, and whether it should be used routinely, or in selected cases. Shamiyeh and co-workers addressed this issue by calculating the mean hiatal surface area (HSA)[32]. The authors found the average HSA was 5.84 cm2 and suggested HSA can be used for the decision to use mesh. Although the use of a prosthetic mesh seems to significantly reduce the risk for recurrence[33,34], it is not free of complications. Erosion into the gastrointestinal organs is the most feared complication when a mesh is used in the hiatus. Until recently, only a few mesh erosions were reported as single cases in the last 15 years[35]. In 2009, Stadlhuber et al[36] reported 28 patients with mesh complications by gathering case data from the expert esophageal surgeons. The authors suggested that the incidence mesh complications may be greater than estimated. Reinforced hiatoplasty has become routine in our early experience, even in GERD patients with small hiatal hernias. U-shaped polypropylene grafts were the preferred type of mesh. We did not observe a mesh complication in more than 700 patients. Because of the fear of mesh erosion, we used grafts more selectively after we read Stadlhuber’s paper.

Adding a fundoplication procedure after the repair of the hiatus is also an issue of debate. Some surgeons recommend its selective application in patients with associated GERD[37]. Others advocate routine application because extensive dissection of the esophagus will result in GERD[38]. Nissen fundoplication is the most commonly used procedure. We routinely performed Toupet fundoplication in the present series. We can provide more fixation of the gastric fundus with more sutures. As the majority of these patients are over 65 years old, they have baseline esophageal dysmotility, and total fundoplication may result in dysphagia[39].

As a result of negative intrathoracic pressure, there is always a tendency for the wrap to migrate back to the thorax following the repair of giant hiatal hernias. Anterior gastropexy was recommended to overcome this problem. Ponsky et al[40] reported a prospective study of 31 patients who underwent laparoscopic PEH repair. The authors did not observe recurrence during the 21 mo follow-up period. We believe gastropexy should not be an option in patients who have IGV, as it may create a new axis that can lead to intra-abdominal volvulus.

In conclusion, laparoscopic management of IGV is a safe procedure and should be the first option in the treatment algorithm. With careful attention the details, such as total excision of the hernia sac, provision of an adequate esophageal length with full mobilization of the esophagus, tensionless hiatoplasty, and a floppy fundoplication, long-term success is possible. This procedure is most likely the most technically demanding procedure among the benign foregut diseases and requires advanced laparoscopic skills. The best outcomes can be achieved by surgeons with extensive experience, especially in laparoscopic anti-reflux surgery, as there is no learning curve for this rare condition.

Giant hiatal hernias are frequently associated with catastrophic complications such as obstruction, perforation and bleeding. Intra-thoracic gastric volvulus (IGV) is the rarest type and represents end stage of giant hiatal hernias before these complications occur.

Minimally invasive approaches for the treatment of foregut diseases are increasing worldwide. Laparoscopic management of IGV is probably most technically demanding procedure among the benign foregut diseases. The authors have focused on technically details and preoperative work-up in the management of this uncommon condition.

Because of the rarity of IGV there is still no prospective randomize study which compares different surgical approaches and controversy exists regarding which surgical approach should be preferred such as; trans-abdominal vs trans-thoracic, open vs laparoscopic, hiatal closure with primary suture vs the use of meshes and the necessity of fundoplication. Laparoscopic approach was the procedure of choice as the authors have extensive experience in laparoscopic anti-reflux surgery. Total sac excision, tensionless hiatoplasty with mesh and Toupet fundoplication were performed in all patients without mortality and minimal morbidity.

With careful attention the details, laparoscopic management of IGV is a safe procedure.

IGV is defined as transmigration of the whole stomach into the thorax by rotating 180 degrees around its longitudinal or transverse axis.

The authors have described their experience well in the management of this rare type of giant hiatal hernia.

| 1. | Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54:710-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1256] [Cited by in RCA: 1272] [Article Influence: 60.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Skinner DB, Belsey RH. Surgical management of esophageal reflux and hiatus hernia. Long-term results with 1,030 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1967;53:33-54. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Hill LD. Incarcerated paraesophageal hernia. A surgical emergency. Am J Surg. 1973;126:286-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Treacy PJ, Jamieson GG. An approach to the management of para-oesophageal hiatus hernias. Aust N Z J Surg. 1987;57:813-817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cuschieri A, Shimi S, Nathanson LK. Laparoscopic reduction, crural repair, and fundoplication of large hiatal hernia. Am J Surg. 1992;163:425-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Priego P, Ruiz-Tovar J, Pérez de Oteyza J. Long-term results of giant hiatal hernia mesh repair and antireflux laparoscopic surgery for gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012;22:139-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Louie BE, Blitz M, Farivar AS, Orlina J, Aye RW. Repair of symptomatic giant paraesophageal hernias in elderly (> 70 years) patients results in improved quality of life. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:389-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Livingston CD, Jones HL, Askew RE, Victor BE, Askew RE. Laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair in patients with poor esophageal motility or paraesophageal herniation. Am Surg. 2001;67:987-991. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Davis SS. Current controversies in paraesophageal hernia repair. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:959-978, vi. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tekin K, Toydemir T, Yerdel MA. Is laparoscopic antireflux surgery safe and effective in obese patients? Surg Endosc. 2012;26:86-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Toydemir T, Tekin K, Yerdel MA. Laparoscopic Nissen versus Toupet fundoplication: assessment of operative outcomes. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2011;21:669-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wo JM, Branum GD, Hunter JG, Trus TN, Mauren SJ, Waring JP. Clinical features of type III (mixed) paraesophageal hernia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:914-916. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Fuller CB, Hagen JA, DeMeester TR, Peters JH, Ritter M, Bremmer CG. The role of fundoplication in the treatment of type II paraesophageal hernia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;111:655-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Schieman C, Grondin SC. Paraesophageal hernia: clinical presentation, evaluation, and management controversies. Thorac Surg Clin. 2009;19:473-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Inaba K, Sakurai Y, Isogaki J, Komori Y, Uyama I. Laparoscopic repair of hiatal hernia with mesenterioaxial volvulus of the stomach. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2054-2057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gockel I, Heintz A, Trinh TT, Domeyer M, Dahmen A, Junginger T. Laparoscopic anterior semifundoplication in patients with intrathoracic stomach. Am Surg. 2008;74:15-19. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Salameh B, Pallati PK, Mittal SK. Incarcerated intrathoracic stomach with antral ischemia resulting in gastric outlet obstruction: a case report. Dis Esophagus. 2008;21:189-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Malik AI, Siddiqui MN, Oke OO. Options in the treatment of totally intrathoracic stomach with volvulus. J Pak Med Assoc. 2007;57:261-263. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Rathore MA, Andrabi SI, Ahmad J, McMurray AH. Intrathoracic meso-axial chronic gastric volvulus: erroneously investigated as coronary disease. Int J Surg. 2008;6:e92-e93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Golash V. Laparoscopic reduction of acute intrathoracic herniation of colon, omentum and gastric volvulus. J Minim Access Surg. 2006;2:76-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Iannelli A, Fabiani P, Karimdjee BS, Habre J, Lopez S, Gugenheim J. Laparoscopic repair of intrathoracic mesenterioaxial volvulus of the stomach in an adult: report of a case. Surg Today. 2003;33:761-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Krähenbühl L, Schäfer M, Farhadi J, Renzulli P, Seiler CA, Büchler MW. Laparoscopic treatment of large paraesophageal hernia with totally intrathoracic stomach. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:231-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Katkhouda N, Mavor E, Achanta K, Friedlander MH, Grant SW, Essani R, Mason RJ, Foster M, Mouiel J. Laparoscopic repair of chronic intrathoracic gastric volvulus. Surgery. 2000;128:784-790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kim HH, Park SJ, Park MI, Moon W. Acute Intrathoracic Gastric Volvulus due to Diaphragmatic Hernia: A Rare Emergency Easily Overlooked. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2011;5:272-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Liem NT, Nhat LQ, Tuan TM, Dung le A, Ung NQ, Dien TM. Thoracoscopic repair for congenital diaphragmatic hernia: experience with 139 cases. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2011;21:267-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Edye M, Salky B, Posner A, Fierer A. Sac excision is essential to adequate laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernia. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1259-1263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lal DR, Pellegrini CA, Oelschlager BK. Laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernia. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:105-118, x. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Mittal SK, Awad ZT, Tasset M, Filipi CJ, Dickason TJ, Shinno Y, Marsh RE, Tomonaga TJ, Lerner C. The preoperative predictability of the short esophagus in patients with stricture or paraesophageal hernia. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:464-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Maziak DE, Todd TR, Pearson FG. Massive hiatus hernia: evaluation and surgical management. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;115:53-60; discussion 61-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Luketich JD, Raja S, Fernando HC, Campbell W, Christie NA, Buenaventura PO, Weigel TL, Keenan RJ, Schauer PR. Laparoscopic repair of giant paraesophageal hernia: 100 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2000;232:608-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Altorki NK, Yankelevitz D, Skinner DB. Massive hiatal hernias: the anatomic basis of repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;115:828-835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Teo YC, Yong FF, Poh CY, Yan YK, Chua GL. Manganese-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of nitrogen nucleophiles with aryl halides in water. Chem Commun (Camb). 2009;6258-6260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Soricelli E, Basso N, Genco A, Cipriano M. Long-term results of hiatal hernia mesh repair and antireflux laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2499-2504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Johnson JM, Carbonell AM, Carmody BJ, Jamal MK, Maher JW, Kellum JM, DeMaria EJ. Laparoscopic mesh hiatoplasty for paraesophageal hernias and fundoplications: a critical analysis of the available literature. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:362-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Carlson MA, Condon RE, Ludwig KA, Schulte WJ. Management of intrathoracic stomach with polypropylene mesh prosthesis reinforced transabdominal hiatus hernia repair. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:227-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Stadlhuber RJ, Sherif AE, Mittal SK, Fitzgibbons RJ, Michael Brunt L, Hunter JG, Demeester TR, Swanstrom LL, Daniel Smith C, Filipi CJ. Mesh complications after prosthetic reinforcement of hiatal closure: a 28-case series. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1219-1226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Myers GA, Harms BA, Starling JR. Management of paraesophageal hernia with a selective approach to antireflux surgery. Am J Surg. 1995;170:375-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Casabella F, Sinanan M, Horgan S, Pellegrini CA. Systematic use of gastric fundoplication in laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernias. Am J Surg. 1996;171:485-489. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Broeders JA, Mauritz FA, Ahmed Ali U, Draaisma WA, Ruurda JP, Gooszen HG, Smout AJ, Broeders IA, Hazebroek EJ. Systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopic Nissen (posterior total) versus Toupet (posterior partial) fundoplication for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1318-1330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 40. | Ponsky J, Rosen M, Fanning A, Malm J. Anterior gastropexy may reduce the recurrence rate after laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1036-1041. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewers Kate V, Vettoretto N S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Ma S