Published online Aug 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i31.5131

Revised: June 3, 2013

Accepted: July 18, 2013

Published online: August 21, 2013

Processing time: 134 Days and 23.1 Hours

AIM: To establish the frequency and clinical features of connective tissue diseases (CTDs) in a cohort of Chinese patients with primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC).

METHODS: Three-hundred and twenty-two Chinese PBC patients were screened for the presence of CTD, and the systemic involvement was assessed. The differences in clinical features and laboratory findings between PBC patients with and without CTD were documented. The diversity of incidence of CTDs in PBC of different countries and areas was discussed. For the comparison of normally distributed data, Student’s t test was used, while non-parametric test (Wilcoxon test) for the non-normally distributed data and 2 × 2 χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests for the ratio.

RESULTS: One-hundred and fifty (46.6%) PBC patients had one or more CTDs. The most common CTD was Sjögren’s syndrome (SS, 121 cases, 36.2%). There were nine cases of systemic sclerosis (SSc, 2.8%), 12 of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE, 3.7%), nine of rheumatoid arthritis (RA, 2.8%), and 10 of polymyositis (PM, 3.1%) in this cohort. Compared to patients with PBC only, the PBC + SS patients were more likely to have fever and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), higher serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels and more frequent rheumatoid factor (RF) and interstitial lung disease (ILD) incidences; PBC + SSc patients had higher frequency of ILD; PBC + SLE patients had lower white blood cell (WBC) count, hemoglobin (Hb), platelet count, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase and immunoglobulin M levels, but higher frequency of renal involvement; PBC + RA patients had lower Hb, higher serum IgG, alkaline phosphatase, faster ESR and a higher ratio of RF positivity; PBC + PM patients had higher WBC count and a tendency towards myocardial involvement.

CONCLUSION: Besides the common liver manifestation of PBC, systemic involvement and overlaps with other CTDs are not infrequent in Chinese patients. When overlapping with other CTDs, PBC patients manifested some special clinical and laboratory features which may have effect on the prognosis.

Core tip: This study demonstrated that primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a complicated disease that not only involves the liver but also often coexists with other connective tissue diseases (CTDs). Evaluation of our cohort of 322 Chinese PBC patients showed that Sjögren's syndrome was the CTD that most frequently coexisted with PBC. In addition, it was also shown that when CTDs coexist with PBC, the clinical features and the disease course are different from those in patients with PBC alone. Our collective results suggest that Chinese patients with PBC may benefit from assessment of systemic involvement and screening for CTDs through detection of autoantibodies.

- Citation: Wang L, Zhang FC, Chen H, Zhang X, Xu D, Li YZ, Wang Q, Gao LX, Yang YJ, Kong F, Wang K. Connective tissue diseases in primary biliary cirrhosis: A population-based cohort study. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(31): 5131-5137

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i31/5131.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i31.5131

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), which predominantly affects middle-aged women, is histologically characterized by chronic non-suppurative destructive cholangitis. Although the liver is the chief target, PBC may involve multiple systems, such as interstitial lung disease (ILD)[1,2], pulmonary artery hypertension (PAH)[3], and nephritis[4]. PBC is also associated with other connective tissue diseases (CTDs) and autoimmune disorders, such as Sjögren’s syndrome (SS), systemic sclerosis (SSc), and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

These co-existing conditions frequently increase the difficulty in making a diagnosis and treating the disease. They may also change the natural course and prognosis of PBC. We have established a database of PBC patients admitted to our hospital during the past ten years, to serve as a resource of data for studies of PBC features and outcomes. In this report, we describe our analysis of these patients’ data to determine the frequencies of extrahepatic lesions and association of CTDs.

Chinese patients with PBC (294 women, 28 men; age mean: 53 years, range: 20-81 years old), who attended our hospital during 2002-2012, were prospectively entered into our collective database and retrospectively analyzed in this study. PBC diagnosis was made according to the criteria published in the guidelines of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases[5,6]. The majority (91.9%) of the patients resided in northern China, with 23.6% of those individuals being from Beijing.

Diagnosis of SS was made if the patient fulfilled the 2002 European diagnostic criteria[7]. Diagnosis of SSc (including scleroderma) was made according to the 1980 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria[8]. Diagnosis of SLE was made according to the 1997 revised ACR criteria[9] and the 2009 Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinic revision of the ACR classification criteria for SLE[10]. Diagnosis and classification of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) were made according to the 1987 revised ACR[11] and 2010 ACR/European League Against Rheumatism criteria[12]. Diagnoses of polymyositis (PM) or dermatomyositis (DM) were made according to the criteria reported by Bohan and Peter[13], and diagnosis of mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) was made according to the 1987 Alarcon-Segovia criteria[14].

Renal involvement was defined by persistent protein urea of > 0.5 g/d, and/or glomerular haematuria, and/or cellular casts[15]. Cardiac involvement was defined by the presence of cardiomyopathy, pericarditis, or arrhythmia.

SPSS version 11.5 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) was used for statistical analysis of the data. Main results were presented as mean ± SD. According to the type and distribution of the data, the statistical significance was estimated by Student’s t test, Wilcoxon test, or 2 × 2 χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests. P values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Of the 322 PBC patients enrolled in the study, the mean time from onset of symptoms to diagnosis was 5.8 years. Anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) was present in 87.0% of the patients, while anti-mitochondrial antibody (AMA) was present in 90.9% of the patients, among which 90.3% were also positive for the M2 subtype of AMA (AMA-M2). Seventy-two (22.4%) of the total patients underwent liver biopsy (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Cohort representation |

| Sex, female/male | 294/28 |

| Age (yr) | 53 ± 12 |

| Duration of disease (yr) | 5.8 ± 3.5 |

| Mayo risk score | 4.5 ± 1.1 |

| Positive ANA | 275/316 (87.0) |

| Positive AMA | 290/319 (90.9) |

| Positive AMA-M2 | 262/290 (90.3) |

| Titers of AMA-M2 (IU/mL) | 139.6 ± 107.9 |

| Liver biopsy | 72 (22.4) |

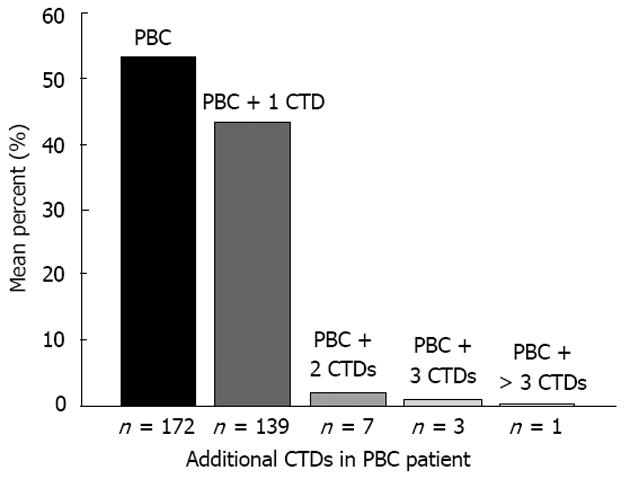

One-hundred and fifty (46.6%) of the patients had CTDs, 11 (3.4%) of which had two or more CTDs (Figure 1). SS (121 cases, 36.2%) was the most frequent CTD represented. There were nine cases of SSc (2.8%), 12 of SLE (3.7%), 9 of RA (2.8%), and 10 of PM (3.1%) in this cohort. no DM or MCTD coexisted with PBC.

The incidence of PBC + SS in the current study was significantly higher than that reported in either the United Kingdom study[16] (37.6% vs 25.0%, P = 0.006) or the Italy study[17] (37.6% vs 3.5%, P = 0.000), while the frequency of PBC + SSc was much lower (2.8% vs 8.0%, P = 0.017; 2.8% vs 12.3%, P = 0.000). The frequency of RA in the current study was less than that in the UK study (2.8% vs 17.0%, P = 0.000) but about the same as in the Italy study. The frequencies of PBC + SLE, + PM and + MCTD were not different between the three studies (Table 2).

| Wang et alChina | Watt et al[16]United Kingdom | Marasini et al[17]Italy | |

| PBC | 322 | 160 | 170 |

| CTDs in PBC | 150 (46.6) | 84 (53.0) | 62 (36.5) |

| PBC + SS | 121 (37.6) | 40 (25.0)a | 6 (3.5)a |

| PBC + SSc | 9 (2.8) | 12 (8.0)a | 21 (12.3)a |

| PBC + SLE | 12 (3.7) | 2 (1.3) | 3 (1.8) |

| PBC + RA | 9 (2.8) | 27 (17.0)a | 3 (1.8) |

| PBC + PM | 10 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) |

| PBC + MCTD | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) |

There were no significant differences between PBC patients with and without CTDs in terms of sex, age, incidences of Raynaud’s phenomenon (RP) or PAH, or levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), ANA, AMA, or AMA-M2 (Table 3).

| PBC (n =172) | PBC + SS (n =121) | PBC + SSc (n = 9) | PBC + SLE (n =12) | PBC + RA (n = 9) | PBC + PM (n = 10) | |

| Female/male | 153/19 | 112/9 | 9/0 | 12/0 | 7/2 | 7/3 |

| Age (yr) | 53 ± 11 | 53 ± 12 | 51 ± 61 | 50 ± 91 | 59 ± 121 | 53 ± 81 |

| Fever | 11 (6.4) | 19 (15.7)a | 0 (0) | 3 (25.0) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (10.0) |

| RP | 32 (18.6) | 23 (19.0) | 4 (44.4) | 5 (41.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Arthralgia | 37 (21.5) | 31 (25.6) | 2 (22.2) | 4 (33.3) | 9 (100)a | 1 (10) |

| ILD | 13 (7.6) | 27 (22.3)a | 3 (33.3)a | 0 (0) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (20) |

| PAH | 11 (6.4) | 13 (10.7) | 2 (22.2) | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Cardiac | 5 (2.9) | 3 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (40.0)a |

| Renal | 9 (5.2) | 8 (6.6) | 1 (11.1) | 4 (33.3)a | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| WBC (109/L) | 5.7 ± 2.6 | 5.0 ± 2.9 | 5.7 ± 2.81 | 4.0 ± 1.11a | 5.7 ± 2.41 | 7.9 ± 3.41a |

| Hb (g/L) | 126 ± 20 | 118 ± 18 | 120 ± 231 | 102 ± 201a | 110 ± 111a | 127 ± 161 |

| PLT (109/L) | 189 ± 82 | 135 ± 69 | 190 ± 103 | 96 ± 75a | 247 ± 142 | 206 ± 91 |

| ALT (U/L) | 79 ± 76 | 91± 75 | 76 ± 621 | 69 ± 721 | 56 ± 461 | 73 ± 561 |

| AST (U/L) | 76± 62 | 90 ± 64 | 96 ± 411 | 69 ± 551 | 79 ± 521 | 73 ± 331 |

| ALP (U/L) | 250 ± 221 | 287 ± 224 | 291 ± 1661 | 173 ± 981 | 487 ± 4111a | 153 ± 981 |

| γ-GT (U/L) | 320 ± 340 | 309 ± 290 | 344 ± 3461 | 207 ± 1531a | 239 ± 1661 | 264 ± 2751 |

| IgG (g/L) | 17.1 ± 6.2 | 21.0 ± 12.4a | 17.3 ± 5.81 | 15.8 ± 5.21 | 22.2 ± 5.11a | 16.4 ± 4.41 |

| IgM (g/L) | 4.5 ± 4.7 | 4.3 ± 3.9 | 3.4 ± 1.81 | 1.9 ± 1.21a | 4.2 ± 3.61 | 5.4 ± 3.11 |

| ESR (mm/1h) | 41 ± 28 | 57 ± 38a | 47 ± 341 | 47 ± 251 | 76 ± 301a | 48 ± 201 |

| RF+ | 31/156 (19.9) | 92/120 (76.7)a | 4/8 (50.0) | 5/11 (45.5) | 9/9 (100)a | 4/10 (40.0) |

| ANA | 142/169 (84.0) | 111/119 (93.3) | 9/9 (100) | 12/12 (100) | 8/9 (88.9) | 10/10 (100) |

| AMA | 153/171 (89.5) | 109/120 (90.8) | 8/9 (88.9) | 11/12 (91.7) | 8/9 (88.9) | 10/10 (100) |

| AMA- M2 (IU/mL) | 147± 125 | 130 ± 105 | 119 ± 1151 | 160 ± 1161 | 139 ± 1181 | 172 ± 1381 |

Compared with PBC patients, the PBC + SS patients had significantly higher incidence of fever (6.4% vs 15.7%, P = 0.010) and ILD (7.6% vs 22.3%, P = 0.000), while the PBC + RA patients had significantly higher incidence of arthralgia (21.5% vs 100%, P = 0.000) and the PBC + SSc patients also had significantly higher incidence of ILD (7.6% vs 33.3%, P = 0.035). Patients with PBC + PM were likely to have cardiac involvement, most frequently cardiomyopathy (40% vs PBC patients: 2.9%, P = 0.001), and renal involvement was more common in patients with PBC + SLE (33.3% vs PBC patients: 5.2%, P = 0.006).

The most common disease coexisting with PBC was SS. Compared to PBC patients without SS, the PBC + SS patients had higher serum level of immunoglobulin G (IgG; 17.1 ± 6.2 g/L vs 21.0 ± 12.4 g/L, P = 0.004), faster erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR; 41 ± 28 mm/h vs 57 ± 38 mm/h, P = 0.032), and higher rates of positivity for rheumatoid factor (RF; 19.9% vs 76.7%, P = 0.000). There were no significant differences in the clinical characteristics of patients who had PBC + SSc and those with PBC alone.

Compared to PBC patients, the PBC + SLE patients had lower white blood cell count (WBC; 5.7 ± 2.6 × 109/L vs 4.0 ± 1.1 × 109/L, P = 0.005), level of hemoglobin (Hb; 126 ± 20 g/L vs 102 ± 20 g/L, P = 0.003), platelet count (PLT; 189 ± 82 × 109/L vs 96 ± 75 × 109/L, P = 0.001), serum levels of γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GT; 320 ± 340 U/L vs 207 ± 153 U/L, P = 0.048), and IgM (4.5 ± 4.7 g/L vs 1.9 ± 1.2 g/L, P = 0.001). Compared to PBC patients without RA, patients with PBC + RA had lower Hb (126 ± 20 g/L vs 110 ± 11 g/L, P = 0.001), but higher levels of serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP, 250 ± 221 U/L vs 487 ± 411 U/L, P = 0.047) and IgG (17.1 ± 6.2 g/L vs 22.2 ± 5.1 g/L, P = 0.004), ESR (41 ± 28 mm/h vs 76 ± 30 mm/h, P = 0.004), and ratio of positive RF (19.9% vs 100.0%, P = 0.009). Compared to PBC patients, patients with PBC + PM had higher WBC count (5.7 ± 2.6 × 109/L vs 7.9 ± 3.4 × 109/L, P = 0.048).

Autoimmune diseases exhibit an increased immune response to self-antigens, occur predominantly in females, and share some similar pathogenic pathways or genetic etiologies[18,19]. Consequently, it is common for more than one autoimmune condition to occur in a single patient. For instance, the classic model of SS shows its secondary nature to SLE[20] and SSc overlapping with PM[21]. Similarly PBC often overlaps with other autoimmune diseases and conditions, thereby causing not only liver damage but also extrahepatic injury.

An epidemiological study from United States showed that one-third of 1032 patients with PBC were affected by another autoimmune disease, most commonly SS, RP, autoimmune thyroid disease, scleroderma, or SLE[22]. Yet another United States-based study reported that about 72% of the PBC patients also had SS, and 20% of PBC patients had joint disease[23]. Similarly, a previous study of the United Kingdom showed that 53% of the PBC patients had at least one additional autoimmune condition, with the most common being SS, autoimmune thyroid disease, RA, and SSc[16]. None of these patients had concomitant PM or DM. An Italian-based study of 170 PBC cases showed that the highest-frequency CTD was SSc (21 cases, 12.3%)[17].

The data from the current study showed that SS was the most common CTD that coexisted with PBC. The frequency was higher compared to rates reported in Europe[16,17]. SS and PBC are both characterized by immune-mediated progressive destruction of the epithelial tissues, with SS mainly affecting the salivary and lacrimal glands and PBC mainly affecting the small bile ducts[24]. Clinically, many PBC patients also present with dry eyes or mouth (47%-73%), and focal lymphocytic infiltration of labial glands (26%-93%)[25-27]. Nevertheless, in these PBC patients, anti-SSA or anti-SSB antibodies were rarely detected, and sequelae were milder than in the primary SS patients. They were also found to express lower levels of human leukocyte antigen-B8, DR3, and DRW52 compared to the primary SS patients[24]. Perhaps, only PBC patients who met the criteria of SS and also had exact anti-SSA or anti-SSB antibodies had really overlapping SS. In the current study, all of the PBC patients who met the criteria of SS were included[7], regardless of whether specific antibodies were present or not, which likely explains the particularly high number of PBC + SS patients in the current study’s cohort. Compared to patients with PBC only, the PBC + SS patients were more likely to have fever and elevated ESR, suggesting that the inflammatory reaction may have been more severe in the concomitant cases. The PBC + SS cases also showed higher serum IgG levels and more frequent RF and ILD incidences; thus, treatment with glucocorticoids or immunosuppressive agents, in addition to ursodesoxycholic acid, might be beneficial for these cases.

SSc was the first reported CTD to coexist with PBC[28]. Although the known molecular targets of SSc and PBC are distinct, the two diseases share similar outcomes: sclerosis in the case of SSc and cirrhosis in the case of PBC. As both conditions result in fibrogenesis, there may be some similar epitopes or sequences in the target antigens of the two diseases that are involved in the effects on the fibrogenic pathway. According to the data from the Italian-based study[17], SSc was the most frequent comorbidity in PBC; moreover, a future study suggested that this rate might be underestimated[29]. In the Chinese-based study, the frequency of PBC + SSc was much lower than that of PBC + SS. In China, SSc cases with only skin involvement usually consult a dermatologist for diagnosis and treatment, instead of a rheumatologist. It is likely that many cases of PBC with SSc remain undiagnosed. On the other hand, prevalence of SSc has been reported to be much higher in North America and Australia than in Japan, another Asian country[30]. The exact epidemiologic data for SSc in China is not available, but considering the similarity in genetic backgrounds of Asian ethnicities it is possible that the incidence and prevalence of SSc in China may be close to that in Japan, and lower than that in Europe. Such a situation may partially explain the observed low frequency of PBC + SSc in our Chinese cohort. Recent study from United Kingdom have demonstrated that patients affected by both PBC and SSc manifested a less aggressive form of liver disease, suggesting an active interaction between the two conditions[31]. Such characteristics were not observed in the current study’s Chinese cohort. Specifically, there were no significant differences in the results of laboratory tests from the PBC patients and the PBC + SSc patients; however, the latter had higher frequency of ILD due to the existence of SSc.

PBC mostly affects middle-aged women, while the majority of SLE cases occur in women of childbearing age[32]. Therefore, the likelihood of co-existence of PBC and SLE is theoretically low. In fact, the reported frequencies of PBC + SLE in PBC are 1.25%-1.80%[16,17] and in SLE are 1.4%-7.5%[33-35]. In the current Chinese cohort, the frequency of PBC + SLE was 3.7%, which was higher than that of PBC + SSc (2.8%). Compared to patients with PBC alone, the PBC + SLE patients had lower WBC count, Hb, and PLT, and higher frequency of renal involvement, all of which are distinctive features of SLE. The coexistence of SLE in PBC patients appeared to be associated with much less extensive liver damage, as reflected by lower γ-GT and IgM levels. These finding suggest that SLE may protect against progression of PBC by inducing a slower progression to cirrhosis and delaying the need for liver transplantation[36,37].

Arthralgia is a non-specific symptom, which is very common in CTD, and inflammation of multiple joints with arthralgia is characteristic of RA. A study from the United States indicated that the rate of prevalence of RA in PBC patients did not differ from that in healthy controls[22]. However, the incidence of RA in PBC patients in the current study (2.8%) was higher than the incidence of 0.5%-1.0%[38] reported worldwide, but less than that reported in the United Kingdom study[16]. In the current cohort, the PBC + RA patients had lower Hb levels but higher serum levels of IgG, faster ESR and a higher ratio of RF positivity. They also had elevated serum ALP level, from which we conclude that coexistence of RA maybe a negative-prognosis factor for PBC[36,37].

Regarding the overlap of PBC and PM/DM, the current data did not confirm that it was as rare as reported in the previous studies in the literature. Interestingly, no cases of PBC + DM were detected. In contrast, there have been several case reports of PBC complicated by PM[39-41], and many of these cases have been asymptomatic or showing mild (early) histological changes. Higher WBC count meant more severe inflammation in PBC + PM. The PBC + PM patients in our Chinese cohort showed a tendency towards myocardial involvement, and that rate was much higher than that in the PM/DM patients[42]. It is unclear why the heart is particularly involved in PBC complicated with PM. Treatment with high-dose steroids or even pulse therapy is a particularly effective strategy[43] and has been shown to decrease mortality[44]. It is intriguing to consider that the pathogenesis of this syndrome might be related to the presence of various subtypes of AMA[45]; however, further studies are necessary to investigate whether the preferential myocardial involvement is a diagnostic finding in patients with PBC and PM.

There are several limitations inherent to the current study’s design, which may have affected the results. Less than one-fourth of the patients underwent liver biopsy, which precluded our ability to perform statistical analyses of the differential pathologic features in patients with CTDs and those without CTDs. In addition, the retrospective and descriptive nature of the study restricted our investigations to only the fundamental relationship between PBC and CTDs. Future studies should be designed to investigate the relation with genetics and immune regulator factors to help identify common and distinct pathways involved in pathogeneses of the various CTDs. Finally, the follow-up was relatively short, and longer-term follow-up will help to determine the differential prognosis and mortality profiles of the various CTDs.

In conclusion, many CTDs coexist with PBC, which suggests that PBC and CTDs may share similar pathogenic mechanisms. When various CTDs coexist with PBC, different manifestations and some specific organ involvement may appear. PBC is a systemic autoimmune disease and not organ-specific. Clinicians should screen for CTDs in PBC patients, especially those who have RP, renal manifestation, or signs of involvement of other organ systems. Detailed medical history should be obtained, and laboratory examination of autoantibodies, such as ANA, should be performed to screen for co-existing CTDs and PBC.

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is often thought of as an organ-specific autoimmune disease which mainly targets the liver. However, accumulating evidence has indicated that PBC may involve multiple systems and may be associated with other connective tissue diseases (CTDs). It remains unknown whether these complicated PBC cases have distinctive clinical features and/or prognoses, especially in ethnic Chinese.

The current study assessed the frequency of extrahepatic lesions and the association of CTDs in a cohort of 322 Chinese patients with PBC. In addition, the clinical and laboratory features were compared between the subsets of PBC patients with and without various CTDs.

According to some studies from Europe, systemic sclerosis is the CTD that most frequently coexists with PBC. However, in the current study of a Chinese cohort, Sjögren’s syndrome was the CTD that most frequently coexisted with PBC. This report is the first retrospective cohort study to investigate the differences in the clinical features and extrahepatic involvement between PBC patients with and without CTDs.

PBC is a systemic autoimmune disease and without organ-specificity. It is necessary to evaluate CTDs in PBC patients, especially those with Raynaud phenomenon, renal manifestation, and signs of involvement of multiple organ systems. Detailed collection of medical history and laboratory examination of related autoantibodies should be performed to help diagnose cases of coexisting CTDs and PBC.

PBC is characterized by chronic non-suppurative destructive cholangitis and presence of anti-mitochondrial antibody. It ultimately progresses to cirrhosis and hepatic failure. PBC is an autoimmune liver disease that may involve multiple systems and may be associated with other CTDs.

This is a descriptive study in which the authors analyzed the frequency and clinical features of CTDs in a cohort of 322 Chinese patients with PBC. The results showed that there were some interesting manifestations in the PBC patients with other CTDs and suggest that assessment of systemic involvements and examination of associated autoantibodies may be beneficial for patients with PBC.

| 1. | Shen M, Zhang F, Zhang X. Primary biliary cirrhosis complicated with interstitial lung disease: a prospective study in 178 patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:676-679. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Liu B, Zhang FC, Zhang ZL, Zhang W, Gao LX. Interstitial lung disease and Sjögren’s syndrome in primary biliary cirrhosis: a causal or casual association? Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:1299-1306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shen M, Zhang F, Zhang X. Pulmonary hypertension in primary biliary cirrhosis: a prospective study in 178 patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:219-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sakamaki Y, Hayashi M, Wakino S, Fukuda S, Konishi K, Hashiguchi A, Hayashi K, Itoh H. A case of membranous nephropathy with primary biliary cirrhosis and cyclosporine-induced remission. Intern Med. 2011;50:233-238. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Heathcote EJ. Management of primary biliary cirrhosis. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases practice guidelines. Hepatology. 2000;31:1005-1013. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Lindor KD, Gershwin ME, Poupon R, Kaplan M, Bergasa NV, Heathcote EJ. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2009;50:291-308. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Jonsson R, Moutsopoulos HM, Alexander EL, Carsons SE, Daniels TE, Fox PC, Fox RI, Kassan SS. Classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:554-558. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Subcommittee for scleroderma criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:581-590. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcón GS, Gordon C, Merrill JT, Fortin PR, Bruce IN, Isenberg D, Wallace DJ, Nived O. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2677-2686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2816] [Cited by in RCA: 3707] [Article Influence: 264.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, Healey LA, Kaplan SR, Liang MH, Luthra HS. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315-324. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO, Birnbaum NS, Burmester GR, Bykerk VP, Cohen MD. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2569-2581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6830] [Cited by in RCA: 6463] [Article Influence: 403.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 13. | Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1975;292:344-347. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Alarcón-Segovia D, Villareal M. Classification and diagnostic criteria for mixed connective tissue disease. Mixed connective tissue disease and antinuclear antibodies. Amsterdam: Elsevier 1987; 33-40. |

| 15. | Hahn BH, McMahon MA, Wilkinson A, Wallace WD, Daikh DI, Fitzgerald JD, Karpouzas GA, Merrill JT, Wallace DJ, Yazdany J. American College of Rheumatology guidelines for screening, treatment, and management of lupus nephritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken. ). 2012;64:797-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1040] [Cited by in RCA: 1051] [Article Influence: 75.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Watt FE, James OF, Jones DE. Patterns of autoimmunity in primary biliary cirrhosis patients and their families: a population-based cohort study. QJM. 2004;97:397-406. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Marasini B, Gagetta M, Rossi V, Ferrari P. Rheumatic disorders and primary biliary cirrhosis: an appraisal of 170 Italian patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:1046-1049. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Peeva E. Reproductive immunology: a focus on the role of female sex hormones and other gender-related factors. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2011;40:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dieudé P, Boileau C, Allanore Y. Immunogenetics of systemic sclerosis. Autoimmun Rev. 2011;10:282-290. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Baer AN, Maynard JW, Shaikh F, Magder LS, Petri M. Secondary Sjogren’s syndrome in systemic lupus erythematosus defines a distinct disease subset. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1143-1149. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Kubo M, Ihn H, Kuwana M, Asano Y, Tamaki T, Yamane K, Tamaki K. Anti-U5 snRNP antibody as a possible serological marker for scleroderma-polymyositis overlap. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2002;41:531-534. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Gershwin ME, Selmi C, Worman HJ, Gold EB, Watnik M, Utts J, Lindor KD, Kaplan MM, Vierling JM. Risk factors and comorbidities in primary biliary cirrhosis: a controlled interview-based study of 1032 patients. Hepatology. 2005;42:1194-1202. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Bach N, Odin JA. Primary biliary cirrhosis: a Mount Sinai perspective. Mt Sinai J Med. 2003;70:242-250. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Selmi C, Meroni PL, Gershwin ME. Primary biliary cirrhosis and Sjögren’s syndrome: autoimmune epithelitis. J Autoimmun. 2012;39:34-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kaplan MJ, Ike RW. The liver is a common non-exocrine target in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a retrospective review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2002;2:21. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Tsianos EV, Hoofnagle JH, Fox PC, Alspaugh M, Jones EA, Schafer DF, Moutsopoulos HM. Sjögren’s syndrome in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1990;11:730-734. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Uddenfeldt P, Danielsson A, Forssell A, Holm M, Ostberg Y. Features of Sjögren’s syndrome in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. J Intern Med. 1991;230:443-448. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Sherlock S, Scheuer PJ. The presentation and diagnosis of 100 patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1973;289:674-678. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Norman GL, Bialek A, Encabo S, Butkiewicz B, Wiechowska-Kozlowska A, Brzosko M, Shums Z, Milkiewicz P. Is prevalence of PBC underestimated in patients with systemic sclerosis? Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:762-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ranque B, Mouthon L. Geoepidemiology of systemic sclerosis. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:A311-A318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Rigamonti C, Shand LM, Feudjo M, Bunn CC, Black CM, Denton CP, Burroughs AK. Clinical features and prognosis of primary biliary cirrhosis associated with systemic sclerosis. Gut. 2006;55:388-394. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Tsokos GC. Systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2110-2121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1845] [Cited by in RCA: 2141] [Article Influence: 142.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Chowdhary VR, Crowson CS, Poterucha JJ, Moder KG. Liver involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus: case review of 40 patients. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:2159-2164. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Takahashi A, Abe K, Yokokawa J, Iwadate H, Kobayashi H, Watanabe H, Irisawa A, Ohira H. Clinical features of liver dysfunction in collagen diseases. Hepatol Res. 2010;40:1092-1097. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Efe C, Purnak T, Ozaslan E, Ozbalkan Z, Karaaslan Y, Altiparmak E, Muratori P, Wahlin S. Autoimmune liver disease in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a retrospective analysis of 147 cases. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:732-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Corpechot C, Abenavoli L, Rabahi N, Chrétien Y, Andréani T, Johanet C, Chazouillères O, Poupon R. Biochemical response to ursodeoxycholic acid and long-term prognosis in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2008;48:871-877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 451] [Cited by in RCA: 498] [Article Influence: 27.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 37. | Zhang LN, Shi TY, Shi XH, Wang L, Yang YJ, Liu B, Gao LX, Shuai ZW, Kong F, Chen H. Early biochemical response to ursodeoxycholic acid and long-term prognosis of primary biliary cirrhosis: Results of a 14-year cohort study. Hepatology. 2013;58:264-272. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Gabriel SE. The epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2001;27:269-281. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Bondeson J, Veress B, Lindroth Y, Lindgren S. Polymyositis associated with asymptomatic primary biliary cirrhosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1998;16:172-174. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Honma F, Shio K, Monoe K, Kanno Y, Takahashi A, Yokokawa J, Kobayashi H, Watanabe H, Irisawa A, Ohira H. Primary biliary cirrhosis complicated by polymyositis and pulmonary hypertension. Intern Med. 2008;47:667-669. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Kurihara Y, Shishido T, Oku K, Takamatsu M, Ishiguro H, Suzuki A, Sekita T, Shinagawa T, Ishihara T, Nakashima R. Polymyositis associated with autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, and autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura. Mod Rheumatol. 2011;21:325-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Tong SQ, Zhou XF, Zhang FC. The clinical analysis of cardiac manifestation in polymyositis or dermatomyositis. Zhonghua Fengshibingxue Zazhi. 2005;9:605-608. |

| 43. | Matsumoto K, Tanaka H, Yamana S, Kaneko A, Tsuji T, Ryo K, Sekiguchi K, Kawakami F, Kawai H, Hirata K. Successful steroid therapy for heart failure due to myocarditis associated with primary biliary cirrhosis. Can J Cardiol. 2012;28:515.e3-515.e6. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Marie I. Morbidity and mortality in adult polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2012;14:275-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Varga J, Heiman-Patterson T, Muñoz S, Love LA. Myopathy with mitochondrial alterations in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis and antimitochondrial antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36:1468-1475. [PubMed] |

P- Reviewers Lai Q, Roeb E, Seo YS S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY