Published online Aug 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i31.5103

Revised: February 8, 2013

Accepted: March 15, 2013

Published online: August 21, 2013

Processing time: 340 Days and 1.2 Hours

AIM: To compare the efficacy of different doses of sodium phosphate (NaP) and polyethylenglicol (PEG) alone or with bisacodyl for colonic cleansing in constipated and non-constipated patients.

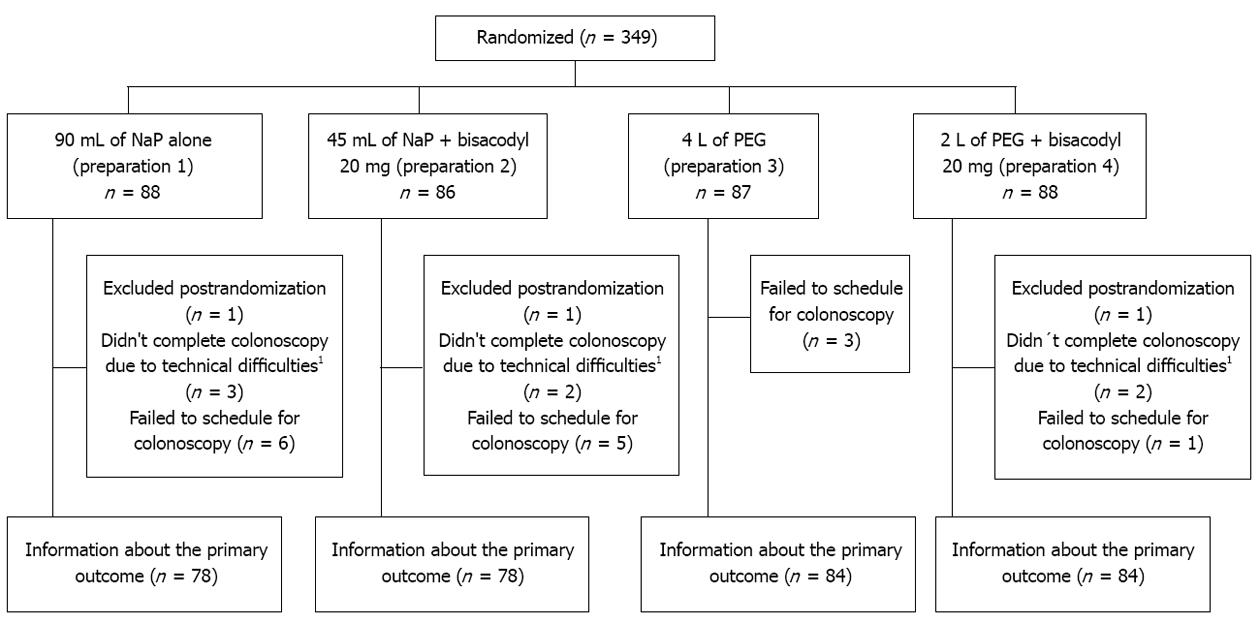

METHODS: Three hundred and forty-nine patients, older than 18 years old, with low risk for renal damage and who were scheduled for outpatient colonoscopy were randomized to receive one of the following preparations (prep): 90 mL of NaP (prep 1); 45 mL of NaP + 20 mg of bisacodyl (prep 2); 4 L of PEG (prep 3) or 2 L of PEG + 20 mg of bisacodyl (prep 4). Randomization was stratified by constipation. Patients, endoscopists, endoscopists’ assistants and data analysts were blinded. A blinding challenge was performed to endoscopist in order to reassure blinding. The primary outcome was the efficacy of colonic cleansing using a previous reported scale. Secondary outcomes were tolerability, compliance, side effects, endoscopist perception about the necessity to repeat the study due to an inadequate colonic preparation and patient overall perceptions.

RESULTS: Information about the primary outcome was obtained from 324 patients (93%). There were no significant differences regarding the preparation quality among different groups in the overall analysis. Compliance was higher in the NaP preparations being even higher in half-dose with bisacodyl: 94% (prep 1), 100% (prep 2), 81% (prep 3) and 87% (prep 4) (2 vs 1, 3 and 4, P < 0.01; 1 vs 3, 4, P < 0.05). The combination of bisacodyl with NaP was associated with insomnia (P = 0.04). In non-constipated patients the preparation quality was also similar between different groups, but endoscopist appraisal about the need to repeat the study was more frequent in the half-dose PEG plus bisacodyl than in whole dose NaP preparation: 11% (prep 4) vs 2% (prep 1) (P < 0.05). Compliance in this group was also higher with the NaP preparations: 95% (prep 1), 100% (prep2) vs 80% (prep 3) (P < 0.05). Bisacodyl was associated with abdominal pain: 13% (prep 1), 31% (prep 2), 21% (prep 3) and 29% (prep 4), (2, 4 vs 1, 2, P < 0.05). In constipated patients the combination of NaP plus bisacodyl presented higher rates of satisfactory colonic cleansing than whole those PEG: 95% (prep 2) vs 66% (prep 3) (P = 0.03). Preparations containing bisacodyl were not associated with adverse effects in constipated patients.

CONCLUSION: In non-constipated patients, compliance is higher with NaP preparations, and bisacodyl is related to adverse effects. In constipated patients NaP plus bisacodyl is the most effective preparation.

Core tip: Colonoscopy has become the standard procedure for the diagnosis and treatment of colon diseases. Adequate bowel cleansing is essential for a high-quality effective and safe colonoscopy. In non-constipated patients, compliance is higher with sodium phosphate (NaP) preparations, and bisacodyl is related to adverse effects. In constipated patients NaP plus bisacodyl is the most effective preparation.

- Citation: Pereyra L, Cimmino D, González Malla C, Laporte M, Rotholtz N, Peczan C, Lencinas S, Pedreira S, Catalano H, Boerr L. Colonic preparation before colonoscopy in constipated and non-constipated patients: A randomized study. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(31): 5103-5110

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i31/5103.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i31.5103

Colonoscopy has become the standard procedure for the diagnosis and treatment of colon diseases[1]. An adequate colonic cleansing is necessary for a proper evaluation of the entire colonic mucosa and therefore for achieving a high quality colonoscopy[2]. Sodium phosphate (NaP) is a small volume hyperosmotic solution that provides effective colonic cleansing in preparation for colonoscopy. In the past years the popularity of orally administered NaP has increased because of its superior tolerance by patients compared with large-volume cleansing agents such as polyethylene glycol electrolyte solutions[3-5]. Although it presents a safety profile similar to other colonic cleansing agents, serious adverse events have been reported when administered in high volume or in patients with contraindications to NaP[6]. Polyethylenglicol (PEG) solutions are the most commonly used laxatives for colonic cleansing because of their safety profile and lack of contraindication. However, unpleasant taste and large volume of PEG lead to poor compliance and result in patient dissatisfaction. The two aforementioned agents are the most frequently used for colonic cleansing in many countries and despite the significant heterogeneity between different studies comparing them for colonic preparation, a systematic review showed similar adequate preparation rates, 75% for NaP and 71% for PEG[7,8]. Numerous clinical trials have also assessed prokinetic (metoclopramide, cisapride and tegazerod)[9-13] and laxative agents (magnesium citrate and bisacodyl)[14-16] associated with standard or lower volumes of this colon cleansing agents. Sharma et al[14] found that pretreatment with magnesium citrate or bisacodyl in addition to half-dose of PEG was associated with better preparation quality and patient satisfaction than full-dose of PEG. To our best knowledge, there is no study directly comparing whole and half-dose of PEG and NaP alone or in combination with bisacodyl in constipated and non-constipated patients. The aim of this study was to compare the efficacy and tolerability of whole doses of NaP and PEG and half-doses of those agents in combination with bisacodyl for colonic cleansing in constipated and non-constipated patients.

This was a randomized, double-blind, four-arm study stratified by constipation. The study was carried out in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. All patients included in the study signed an informed consent form. The human ethics committee from our institution approved the protocol.

All patients older than 18 years old who were scheduled for an elective outpatient’s colonoscopy were eligible for participating in the study and were randomized in a 6-mo period (June-December 2011). As safety issues about NaP solutions have emerged, we only included healthy patients following the United States Food and Drug Administration recommendation to avoid renal damage. Patients were excluded if they presented one or more of the following characteristics: age younger than 18 years old, were hospitalized for any reason, hypersensibility to any of the components of PEG, NaP or bisacodyl, were under more than one antihypertensive medication, presented history of diarrhea (more than 3 bowel movements a day), acute or chronic renal failure, cardiovascular disease (history of myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, unstable angina pectoris, unstable hypertension and/or cardiac arrhythmia), ascites, electrolite inbalance (hiponatremia, hipokalemia, hipocalcemia, hipomagnesemia or hyperphosphatemia), inflammatory bowel disease, partial or subtotal colectomy, ileus or suspected intestinal obstruction and pregnancy or breastfeeding, childbearing potential without contraception.

Patients who met all the inclusion criteria and no exclusion criteria were randomly assigned to receive one of the four colonic preparations according to a computer-generated randomization list. Randomization was stratified by constipation in order to make a subgroup analysis of constipated and non-constipated patients at the end of the study. Constipation was defined according to Thompson et al[17] criteria. Allocation was concealed using same color, size and weight closed boxes. The nurses that provided the patients with colonic preparation, the endoscopy assistant that evaluated the preparation compliance, tolerance and adverse reactions, the data analysts; and the endoscopists who evaluated bowel cleansing quality were blinded. If the patients had doubts about the preparation they could make a telephone call to a physician that was not blinded, was not present during colonoscopy nor participated in the endoscopic quality assessment, tolerability questionnaire, or statistical analysis. To reassure that endoscopists were blinded, a blinding challenge was performed after finishing the colonoscopy by asking them which of the four different colonic cleansing agents they thought the patients had received. A kappa coefficient of agreement was used for this purpose. A kappa under 0.3 and a non-significant P value was considered as an adequate blinding.

Prep 1 consisted of 90 mL of NaP alone (Gadolax®, Gador Laboratory, Argentina) 45 mL with four glasses of water at 4:00 pm and the other 45 mL at 8:00 pm of the day before the study. Prep 2 consisted of 45 mL of NaP with four glasses of water and 20 mg of bisacodyl at 4:00 pm the day before the study. Prep 3 consisted of 4 L of PEG (Barex®, Dominguez Laboratory, Argentina) alone starting at 4:00 pm the day before the study at a rate of 250 mL every 15 min until finishing the solution.

Prep 4 consisted of 2 L of PEG starting at the same time and with the same rate as mentioned before for prep 3 plus 20 mg of bisacodyl. Patients in all groups were encouraged to go through the same low fiber diet during the three days before the study and to adhere to a clear liquid diet from 8:00 am to midnight on the day before colonoscopy. Before colonoscopy the patients were asked to answer a questionnaire to assess patient satisfaction, tolerability, and compliance to the preparation. The questionnaire included yes/no responses for tolerance, preparation completed, and specific symptoms (nausea, vomiting, abdominal or chest pain, dizziness, bloating, and poor sleep). Before entering the Endoscopy Unit patients were asked not to reveal their assigned preparation to the Endoscopy Unit staff. Colonoscopies were done by four colonoscopists from the Endoscopic Unit and all studies were done between 7:30 am and 1:00 pm. All studies were performed using the same Storz Videocolonoscope. The quality of colonic cleansing was graded according to a previously reported scale[13] (Table 1). All endoscopists were trained on the scale using previously selected videos of colonoscopy with different colonic cleansing quality. Endoscopists were also asked if they thought there was a need to repeat the study due to inadequate preparation.

| Excellent | No fecal matter or nearly none in the colon, small-to-moderate amounts of clear liquids |

| Good | Small amounts of thin liquid fecal matter seen and easily suctioned, mainly distal to splenic flexure, small lesions may be missed, > 90% mucosa seen |

| Fair | Moderate amounts of thick liquid to semisolid fecal matter seen and suctioned, included proximal to splenic flexure, small lesions may be missed, 90% mucosa seen |

| Poor | Large amounts of solid fecal matter found, precluding a satisfactory study, unacceptable preparation; < 90% mucosa seen |

Statistical analysis were performed using statistical software SPSS for windows 10.0. Knowing that 70% of colonic cleansings are excellent or very good[1-3], a sample size of 88 patients in each group was calculated to detect a 20% difference in primary outcome with 80% of power at a standard level of significance α = 0.05. Categorical variables were compared using the Fisher exact test or χ2 test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Results were analyzed according to the intention-to-treat principle. Handling of loss to follow-up: We evaluated different assumptions about the incidence of events among participants lost to follow-up and the impact of those assumptions on the estimate of effect for the primary outcome. For this purpose, we used the RILTFU/FU as proposed by Akl et al[18]. The RILTFU/FU is defined as the event incidence among those lost to follow-up relative to the event incidence among those followed up. The assumptions we evaluated by combining a range of RILTFU/FU values (1, 1.5, 2, 3.5 and 5) in the intervention group and control group.

A total of 349 patients scheduled for outpatient colonoscopy participated in the study and were randomized to receive one of the four colonic cleansing preparations. Three patients were excluded post-randomization because they met one or more exclusion criteria, 15 patients failed to present to the procedure and 7 presented incomplete colonoscopy because of fixed angulations (4 patients) or colonic neoplasia (3 patients). Finally, of the 346 randomized patients, information about the primary outcome was obtained from 324 patients (93%) (Figure 1). There were no significant differences among the four preparation groups with respect to: age, sex, cecal intubation, and constipation (Table 2).

| Characteristics | Prep 1 | Prep 2 | Prep 3 | Prep 4 | P value |

| Patients | 78 | 78 | 84 | 84 | |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 59 ± 13.2 | 57 ± 11.1 | 60 ± 13.8 | 59 ± 10.9 | NS |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 37 (47) | 40 (51) | 41 (49) | 45 (53) | NS |

| Female | 41 (53) | 38 (49) | 43 (51) | 39 (47) | NS |

| Constipation | 21 (27) | 16 (21) | 15 (12) | 24 (29) | NS |

| Successful cecal intubation | 78 (100) | 78 (100) | 84 (100) | 84 (100) | NS |

There was no significant concordance between the endoscopists presumption and the colonic preparation group that the patients had been assigned to (P = 0.56, κ = 0.019). This observation reassures that the endoscopists were unaware of the assigned groups (blinding).

We obtained information about this outcome for 93% of patients. The quality of colonoscopic visualization was similar in the four different groups (Figure 2A).

Results were dichotomized into satisfactory colonic cleansing (excellent and good) and unsatisfactory (fair and poor). Satisfactory preparations were achieved in similar proportion in the different groups: prep 1, 82%, prep 2, 80%, prep 3, 79% and prep 4, 78% (P > 0.05) (Figure 2B). Endoscopists thought that only 6% of all the patients in this study needed to repeat the study because of inadequate colonic preparation. This was also similar between different preparations: prep 1, 3.4%, prep 2, 4.7%, prep 3, 6.8% and prep 4, 6.8% (P > 0.05) (Figure 2C).

We conducted a separate analysis of constipated and non-constipated patients. In the non-constipated patients, we didn´t find differences in the quality of colonic cleansing (Figure 2B) but the necessity to repeat colonoscopy was more frequent in prep 4 compared to prep 1 (11% vs 2%, P < 0.05) (Figure 2C). In constipated patients, NaP plus bisacodyl preparation (prep 2) achieved higher rate of satisfactory colonic cleansing than those receiving whole dose of PEG (prep 3): 95% vs 66% (P = 0.03) (Figure 2B).

Both preparations containing NaP, presented better compliance than those containing PEG. Preparation was completed by 94% of the patients in prep 1, 100% of patients in prep 2, 81% of the patients in prep 3 and 87% of the patients in prep 4. Therefore, half-dose of NaP plus bysacodyl achieved the highest compliance (prep 2 vs 1, 3 and 4, P < 0.01) followed by full-dose of NaP (prep 1 vs 3 and 4, P < 0.05) (Figure 2D). In non-constipated patients, compliance was also higher in those preparations containing NaP compared to full-dose PEG: 95% (prep 1), 100 % (prep 2) vs 80% (prep 3) (P < 0.05) (Figure 2D). In constipated patients compliance was similar between different preparations.

The preparation was reported as tolerable in 77% of the patients in prep 1, 81% in prep 2, 82% in prep 3 and in 84% in the prep 4, there was no significant difference between the different preparations (P > 0.05). There was also no significant difference in tolerability between preparations in constipated and non-constipated patients (Table 3).

| Adverse effects | Prep 1 | Prep 2 | Prep 3 | Prep 4 | P value | ||||||||||

| Overall | Non-constipated (n = 59) | Constipated (n = 22) | Overall | Non-constipated (n = 58) | Constipated (n = 20) | Overall | Non-constipated (n = 69) | Constipated (n = 15) | Overall | Non-constipated (n = 65) | Constipated (n = 20) | Overall | Non-constipated | Constipated | |

| Tolerability | 62 (77) | 47 (80) | 15 (68) | 63 (81) | 47 (81) | 16 (80) | 69 (82) | 57 (83) | 12 (80) | 71 (84) | 53 (82) | 18 (90) | NS | NS | NS |

| Nausea | 27 (33) | 17 (29) | 10 (13) | 30 (38) | 24 (41) | 6 (30) | 26 (31) | 2 (32) | 4 (26) | 25 (29) | 18 (28) | 7 (35) | NS | NS | NS |

| Vomiting | 6 (7) | 2 (3) | 4 (18) | 3 (4) | 6 (10) | 3 (15) | 9 (11) | 2 (3) | 1 (7) | 6 (7) | 5 (8) | 3 (15) | NS | NS | NS |

| Abdominal pain | 13 (16) | 8 (14) | 5 (23) | 21 (27) | 18 (31) | 3 (15) | 16 (19) | 14 (20) | 2 (13) | 24 (28) | 19 (29) | 5 (33) | 0.2 | < 0.051 | NS |

| Bloating | 25 (31) | 17 (29) | 8 (36) | 21 (27) | 15 (26) | 6 (30) | 27 (32) | 22 (32) | 5 (33) | 24 (28) | 16 (25) | 8 (40) | NS | NS | NS |

| Insomnia | 10 (12) | 9 (15) | 1 (5) | 17 (21) | 14 (24) | 3 (15) | 5 (6) | 4 (6) | 1 (7) | 11 (13) | 10 (15) | 1 (5) | < 0.052 | NS | NS |

| Dizziness | 12 (15) | 10 (17) | 2 (9) | 7 (9) | 6 (10) | 1 (5) | 7 (8.3) | 5 (7) | 2 (13) | 8 (9) | 5 (8) | 3 (15) | NS | NS | NS |

| Chest pain | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | 1 (5) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | NS | NS | NS |

The most frequent adverse effects reported were: nausea (33%), bloating (30%) and abdominal pain (23%). There were no significant differences among different groups with respect to: nausea, vomiting, chest pain, bloating and dizziness (Table 3). Abdominal pain was more frequent in patients that received both preparations containing bisacodyl, prep 1, 16%, prep 2, 27%, prep 3, 19%, prep 4, 28%, but this difference didn´t reach statistical significance in the overall analysis (P = 0.2) (Table 3). The patients receiving NaP and bisacodyl preparations (prep 2) presented more frequently poor sleep than the other groups (P < 0.05) (Table 3). In non-constipated patients, abdominal pain was more frequent in those preparations containing bisacodyl: prep 2 (31%) and prep 4 (29%); compared to those without it: prep 1 (14%) and prep 3 (20%) (P < 0.05) (Table 3). The symptoms profile was similar between different preparations in constipated patients.

Only 21% of all the patients would refuse to take the same colonic preparation in the future and almost 37% would like to try a different preparation. This finding was similar in the different groups. There was also no significant differences in patients perception in different groups in constipated and non-constipated patients.

None of the different assumptions of incidence of events in loss to follow up patients changed significantly the estimate of the effect in the different outcomes.

There is a growing acceptance of colorectal cancer screening with colonoscopy. Its goal is to identify and remove neoplastics polyps; therefore a high-quality preparation that lends to a clear visualization is crucial. Inadequate colonic cleansing could lead to a diminished adenoma detection rate[19-21]. This has been recently shown to be the strongest predictor of interval colorectal cancer[22,23]. However none of the different preparation agents are ideal for colonic cleansing. They present historic rates for adequate cleansing that ranges from 70% to 82%[24-26]. Tolerability and side effects are probably the main issues and represent some of the most important reasons for patient’s refusal to the study[25]. In an attempt to decrease these sides effects, many studies have evaluated different doses of conventional preparation agents and pretreatment with prokinetics or laxative agents, but there is little information about the effect of these preparations in subgroups of constipated and non-constipated patients[7]. In this study we compared two of the most used colonic cleansing agents, PEG and NaP. As in past years, there has been a strong tendency to prepare patients with half doses of this previously mentioned agents associated with bisacodyl because of commercially available preparation kits. We decided to carry out a direct comparison between whole dose of PEG and NaP alone and half doses of these two agents associated with bisacodyl in constipated and non-constipated patients. Our studies main limitations include, single centre study and the use of non-validated scale for the evaluation of primary outcome (quality of colonic preparation) and patient related outcomes (tolerability, adverse events, preferences). Nevertheless, the randomized, double-blind, four-arm study design and the constipated and non-constipated subgroup analysis could provide useful information on how to manage patients that might undergo colonoscopy. Similar to the results reported by previous studies, almost 80% of patients presented to colonoscopy with satisfactory colonic cleansing (excellent or very good). We did not find any difference with respect to quality of colonic cleansing in the different groups, even in those with half doses of NaP and PEG. Preparation quality was also similar in different groups in non-constipated patients, but endoscopists thought that there was a greater necessity to repeat the study due to an inadequate colonic cleansing in prep 4 (half dose of PEG plus bisacodyl) compared to prep 1 (whole dose of NaP) (11% vs 2%, P < 0.05). Although this is a non-validated and subjective outcome; we think it´s interesting to know endoscopist perception, because it represents what they really do in the daily practice and is a patient important outcome. In constipated patients, preparations containing bisacodyl presented higher rates of satisfactory colonic cleansing: 95% (prep 2) and 85% (prep 4) vs 67% (prep 3) and 77% (prep 1). Only NaP plus bisacodyl reached a statistically significant difference compared to whole dose of PEG (95% vs 66%, P = 0.03). The prokinetic effect of the bisacodyl may explain the high rates of satisfactory colonic preparations. Even though a statistical significant difference was only obtained with NaP plus bisacodyl and not with PEG plus bisacodyl, we think that this may be related to the small sample size of the constipated patients subgroup. In the overall analysis, compliance was higher in groups with preparations containing NaP, reaching 100% in the half dose NaP plus bisacodyl group and 94% in the whole dose of NaP. In non-constipated patients, compliance with NaP preparations was higher than whole doses PEG preparation. We were not able to demonstrate higher compliance rates with NaP preparations in constipated patients. However, the observed tendency to higher compliance in these groups along with evidence of previous studies lead us to believe that we were unable to find statistically significant difference due to the small sample size. Tolerability (taste, nausea, etc.) was similar in the different groups. Consequently, we believe that the differences in compliances were related to the volume of the preparations and probably not to tolerability. The most frequent adverse effect was nausea followed by bloating and abdominal pain. None of the different preparations were associated with an antiemetic medication, so we do not know if nausea and probably tolerance could be optimized with this association. Bisacodyl has been previously associated with abdominal cramping. In this study both groups with preparations containing bisacodyl presented higher incidence of abdominal pain: prep 1, 16%, prep 2, 27%, prep 3, 19%, prep 4, 28%, but the difference was not statistically significant. The difference was statistically significant when we analyzed the subgroup of non-constipated patients: prep 1, 14%, prep 2, 31%, prep 3, 21%, prep 4, 29% (P < 0.05). Curiously, constipated patients that received preparation with bisacodyl did not have higher incidence of abdominal pain. We think that constipated patients can present a motility dysfunction that could be optimized with the administration of the bisacodyl and that could explain the difference perception of abdominal pain in constipated and non-constipated patients. In the overall analysis, the combination of NaP with bisacodyl was also associated with higher rates of poor sleep than other preparations. We did not find any previous reports of this association and we do not have a specific explanation for this finding. However, it seems that the bisacodyl adverse effects profile is different in constipated and non-constipated patients, suggesting that constipated patients are less affected by these effects. Although the evaluated preparations presented a high rate of satisfactory colonic cleansing, compliance and a low profile of side effects, almost 37% of all the patients when asked, would prefer to try a different preparation in next colonoscopy. This study shows that none of the preparations agents is ideal, and highlights the need to improve bowel cleansing methods not only to get high quality colonic cleansing, but also to achieve a higher adherence to colonoscopy screening and surveillance programs. In summary, the quality of colonic cleansing and side effects profile of evaluated preparations are different in constipated and none-constipated. In non-constipated patients, preparation quality is similar with whole or half doses of NaP or PEG, alone or in combination with bisacodyl and compliance is higher with NaP preparations. Bisacodyl addition is associated with a higher incidence of adverse events. In constipated patients, the combination of NaP with bisacodyl is the most effective preparation. In this subgroup of patients, bisacodyl addition is not associated with higher incidence of adverse effects as noticed in non-constipated patients.

The authors would like to thank Melissa Ann Kucharczyk and Valeria Fernandez.

Colonoscopy has become the standard procedure for the diagnosis and treatment of colon diseases. Adequate bowel cleansing is essential for a high-quality effective and safe colonoscopy.

Numerous clinical trials have assessed the efficacy of whole or low doses of sodium phosphate (NaP) and polyethylenglicol (PEG) alone or with bisacodyl. There is no information about which is the most suitable preparation regimen for constipated and non-constipated patients.

Their randomized clinical trial compared the efficacy and tolerability of whole and half doses of NaP and PEG alone or associated with bisacodyl preparations and explored the different effect on constipated and none-constipated patients.

Compliance was higher with NaP preparations in non-constipated patients and the addition of bisacodyl was associated with higher incidence of adverse effects. Half-dose of NaP plus bisacodyl was the most effective preparation in constipated patients. Bisacodyl was not associated with adverse effects in constipated patients as noticed in non-constipated patients.

This is a good study in which authors compare the efficacy of different doses of NaP and PEG alone or with bisacodyl for colonic cleansing in constipated and non-constipated patients. The results are interesting and suggest that in non-constipated patients, compliance is higher with NaP preparations, and bisacodyl is related to adverse effects. In constipated patients NaP plus bisacodyl is the most effective preparation.

| 1. | Mihalko SL. Implementation of colonoscopy for mass screening for colon cancer and colonic polyps: efficiency with high quality of care. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37:117-128, vii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers JJ, Burnand B, Vader JP. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:378-384. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Vanner SJ, MacDonald PH, Paterson WG, Prentice RS, Da Costa LR, Beck IT. A randomized prospective trial comparing oral sodium phosphate with standard polyethylene glycol-based lavage solution (Golytely) in the preparation of patients for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:422-427. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Marshall JB, Pineda JJ, Barthel JS, King PD. Prospective, randomized trial comparing sodium phosphate solution with polyethylene glycol-electrolyte lavage for colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:631-634. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Kolts BE, Lyles WE, Achem SR, Burton L, Geller AJ, MacMath T. A comparison of the effectiveness and patient tolerance of oral sodium phosphate, castor oil, and standard electrolyte lavage for colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy preparation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1218-1223. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Hookey LC, Depew WT, Vanner S. The safety profile of oral sodium phosphate for colonic cleansing before colonoscopy in adults. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:895-902. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Wexner SD, Beck DE, Baron TH, Fanelli RD, Hyman N, Shen B, Wasco KE. A consensus document on bowel preparation before colonoscopy: prepared by a task force from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society of Ameican Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES). Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:792-809. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Belsey J, Epstein O, Heresbach D. Systematic review: oral bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:373-384. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Brady CE, DiPalma JA, Pierson WP. Golytely lavage--is metoclopramide necessary? Am J Gastroenterol. 1985;80:180-184. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Martínek J, Hess J, Delarive J, Jornod P, Blum A, Pantoflickova D, Fischer M, Dorta G. Cisapride does not improve precolonoscopy bowel preparation with either sodium phosphate or polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:180-185. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Lazarczyk DA, Stein AD, Courval JM, Desai D. Controlled study of cisapride-assisted lavage preparatory to colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:44-48. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Reiser JR, Rosman AS, Rajendran SK, Berner JS, Korsten MA. The effects of cisapride on the quality and tolerance of colonic lavage: a double-blind randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:481-484. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Abdul-Baki H, Hashash JG, Elhajj II, Azar C, El Zahabi L, Mourad FH, Barada KA, Sharara AI. A randomized, controlled, double-blind trial of the adjunct use of tegaserod in whole-dose or split-dose polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution for colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:294-300; quiz 334, 336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sharma VK, Steinberg EN, Vasudeva R, Howden CW. Randomized, controlled study of pretreatment with magnesium citrate on the quality of colonoscopy preparation with polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage solution. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:541-543. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Sharma VK, Chockalingham SK, Ugheoke EA, Kapur A, Ling PH, Vasudeva R, Howden CW. Prospective, randomized, controlled comparison of the use of polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage solution in four-liter versus two-liter volumes and pretreatment with either magnesium citrate or bisacodyl for colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:167-171. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Afridi SA, Barthel JS, King PD, Pineda JJ, Marshall JB. Prospective, randomized trial comparing a new sodium phosphate-bisacodyl regimen with conventional PEG-ES lavage for outpatient colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:485-489. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, Heaton KW, Irvine EJ, Müller-Lissner SA. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut. 1999;45 Suppl 2:II43-II47. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Akl EA, Briel M, You JJ, Sun X, Johnston BC, Busse JW, Mulla S, Lamontagne F, Bassler D, Vera C. Potential impact on estimated treatment effects of information lost to follow-up in randomised controlled trials (LOST-IT): systematic review. BMJ. 2012;344:e2809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 272] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rembacken B, Hassan C, Riemann JF, Chilton A, Rutter M, Dumonceau JM, Omar M, Ponchon T. Quality in screening colonoscopy: position statement of the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE). Endoscopy. 2012;44:957-968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Gurudu SR, Ramirez FC, Harrison ME, Leighton JA, Crowell MD. Increased adenoma detection rate with system-wide implementation of a split-dose preparation for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:603-608.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Moritz V, Bretthauer M, Ruud HK, Glomsaker T, de Lange T, Sandvei P, Huppertz-Hauss G, Kjellevold Ø, Hoff G. Withdrawal time as a quality indicator for colonoscopy - a nationwide analysis. Endoscopy. 2012;44:476-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jover R, Herráiz M, Alarcón O, Brullet E, Bujanda L, Bustamante M, Campo R, Carreño R, Castells A, Cubiella J. Clinical practice guidelines: quality of colonoscopy in colorectal cancer screening. Endoscopy. 2012;44:444-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 23. | Kaminski MF, Regula J, Kraszewska E, Polkowski M, Wojciechowska U, Didkowska J, Zwierko M, Rupinski M, Nowacki MP, Butruk E. Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the risk of interval cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1795-1803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1287] [Cited by in RCA: 1518] [Article Influence: 94.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Harewood GC, Sharma VK, de Garmo P. Impact of colonoscopy preparation quality on detection of suspected colonic neoplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:76-79. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Ness RM, Manam R, Hoen H, Chalasani N. Predictors of inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1797-1802. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Hsu CW, Imperiale TF. Meta-analysis and cost comparison of polyethylene glycol lavage versus sodium phosphate for colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:276-282. [PubMed] |

P- Reviewer Sheikh RA S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY