Published online Jul 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i28.4520

Revised: April 11, 2013

Accepted: May 16, 2013

Published online: July 28, 2013

Processing time: 164 Days and 8.4 Hours

AIM: To assess the rate of recurrent bleeding of the small bowel in patients with obscure bleeding already undergone capsule endoscopy (CE) with negative results.

METHODS: We reviewed the medical records related to 696 consecutive CE performed from December 2002 to January 2011, focusing our attention on patients with recurrence of obscure bleeding and negative CE. Evaluating the patient follow-up, we analyzed the recurrence rate of obscure bleeding in patient with a negative CE. Actuarial rates of rebleeding during follow-up were calculated, and factors associated with rebleeding were assessed through an univariate and multivariate analysis. A P value of less than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV) of negative CE were calculated.

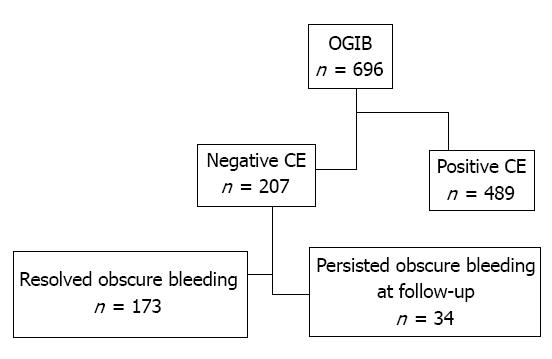

RESULTS: Two hundred and seven out of 696 (29.7%) CE studies resulted negative in patient with obscure/overt gastrointestinal bleeding. Overall, 489 CE (70.2%) were positive studies. The median follow-up was 24 mo (range 12-36 mo). During follow-up, recurrence of obscure bleeding was observed only in 34 out of 207 negative CE patients (16.4%); 26 out of 34 with obscure overt bleeding and 8 out of 34 with obscure occult bleeding. The younger age (< 65 years) and the onset of bleeding such as melena are independent risk factors of rebleeding after a negative CE (OR = 2.6703, 95%CI: 1.1651-6.1202, P = 0.0203; OR 4.7718, 95%CI: 1.9739-11.5350, P = 0.0005). The rebleeding rate (CE+ vs CE-) was 16.4% vs 45.1% (χ2 test, P = 0.00001). The sensitivity, specificity, and PPV and NPV were 93.8%, 100%, 100%, 80.1%, respectively.

CONCLUSION: Patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding and negative CE had a significantly lower rebleeding rate, and further invasive investigations can be deferred.

Core tip: Although capsule endoscopy (CE) is widely used as a first-line diagnostic modality for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after the execution of a work-out negative for gastrointestinal bleeding properly done by following the guidelines proposed by American Gas Association, the rebleeding rate after negative CE varies according to different studies. We tried to elucidate the outcomes after a negative CE for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) and to determine the risk factors associated with rebleeding. Based on the results of our study patients with OGIB and negative CE had a significantly lower rebleeding rate, and further invasive investigations can be deferred.

- Citation: Riccioni ME, Urgesi R, Cianci R, Rizzo G, D’Angelo L, Marmo R, Costamagna G. Negative capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding reliable: Recurrence of bleeding on long-term follow-up. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(28): 4520-4525

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i28/4520.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i28.4520

Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) remains a major clinical challenge. Many instances of OGIB originate from the small bowel, which is beyond the reach of an ordinary endoscope, including an esophagogastroduodenoscope (EGD) and colonoscope. The scene was recently revolutionized by the availability of the capsule endoscopy (CE), which is noninvasive and well tolerated by patients.

CE is currently indicated as part of the workup for OGIB (obscure-overt or obscure-occult), undiagnosed iron deficiency anemia, Crohn’s disease, polyposis syndromes and cancer, celiac disease, for monitoring after small bowel transplant and, occasionally, for undiagnosed abdominal pain or diarrhea[1-5]. Since its development, several studies have compared the diagnostic yield of CE with other modalities commonly used to investigate the small bowel. Many studies have shown CE to be more sensitive and more effective compared with either push enteroscopy or small bowel follow-through[6-20]. The sensitivity and specificity of CE have been cited to be as high as 89% and 95%, respectively[20]. Although many papers have attempted to estimate the effectiveness of CE based on its diagnostic yield, few studies have considered the utility of a negative CE. In fact, only one of them[21-23] has considered a negative CE as a failure.

A great amount of data about a positive CE and its therapeutic and prognostic implications are available in literature. However, few data on the outcomes of patients with a negative CE are available. It is also somewhat more difficult to ascertain the value of a negative test. Previous studies have considered objective measures such as whether a negative test leads to other tests or therapeutic interventions. The impact on patients’ overall outcome remains poorly defined, particularly in patients with OGIB. It remains uncertain that CE findings predict rebleeding.

A negative CE, though it does not confirm a specific diagnosis, may still be useful, because it allows the physician to quit a certain line of investigation, thereby impacting patient care.

We reviewed the medical records of all patients referred to the Digestive Endoscopy Unit of the Catholic University in Rome to undergo a CE analysis for the investigation of OGIB between December 1st, 2002 and January 30th, 2011. All of them presented an overt or occult gastrointestinal bleeding as clinical presentation according to the guidelines of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA)[24]. All patients had undergone both EGD and ileo-colonoscopy resulted negative before to referral for CE.

All patients, opportunely consented, underwent a CE with the PillCam capsule endoscopy system (Given Imaging, Yoqneam, Israel), according to the standard protocols endorsed by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy[25]. All the procedures were performed in an out patient setting, after fasting for 8 h without any bowel preparation. The PillCam small bowel (Given Imaging) was then administered. The patients had a light breakfast 2 h after and a light meal 4 h after the administration of the PillCam as recommended in the standard protocol. After 8 h, they returned to the Endoscopy Unit, data recorder was removed and images were downloaded on the computer. The recordings of CE were reviewed by 2 experienced endoscopists/gastroenterologists independently (Riccioni ME, Urgesi R) at 8-10 frames per second using the Rapid® Reader (version 5.0). When possible, the stomach and the colon were also observed. The interobserver difference in interpretation about any findings was less than 5% and if and when it existed, it was resolved by reexamination.

A positive CE was defined as the presence of CE findings that may account for the clinical bleeding (angiodysplasia, ulcers or erosions, tumor, Crohn’s disease, and active bleeding with no identifiable source), whereas a negative CE was defined as the absence of abnormalities on CE as reason of the bleeding.

In all cases in which CE did not reach the valve or with inadequate small bowel cleansing the examination was repeated. The analysis was considered negative when the second procedure rule out any GI abnormalities[26].

The median follow-up for all patients, strictly monitored for rebleeding, was 24 mo (range 12-36 mo). Patients’ records, including blood tests, hospital admissions (especially for anemia and/or recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding), blood transfusions, need of iron supplementation, additional endoscopies (including push endoscopies), and surgery were considered from the date of the CE. Overt clinical rebleeding was defined as passing melena or fresh blood per rectum with a drop in hemoglobin of 2 g/dL or more. Occult rebleeding was defined as an unexplained hemoglobin drop of more than 2 g/dL in the absence of melena or hematochezia.

We defined patients with no recurrent obscure gastrointestinal bleeding or anemia during follow-up as “negative for rebleeding” and those with a confirmed bleeding source identified by an invasive interventions, clinical rebleeding, or recurrent unexplained anemia (using standardized and published criteria: blood haemoglobin level of < 13.8 g/dL for men, < 11.5 g/dL for postmenopausal women, and < 11 g/dL for pre-menopausal women, with a plasma ferritin level of < 30 μg/L and a mean corpuscular volume of < 80 fL[26]) as “positive for rebleeding”.

The Statistical Package for Social Science (version 13.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) was used for all statistical computation. Actuarial rates of rebleeding during follow-up were calculated, and factors associated with rebleeding were assessed through an univariate and multivariate analysis. A P value of less than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

The sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV) were calculated[27] using as “gold standard” the patients negative for obscure bleeding.

CE indications included obscure overt bleeding (532), obscure occult bleeding (164) and several other indications (282). CE studies resulted negative in 207 out of 696 (29.7%) with obscure/overt gastrointestinal bleeding: 110 male (53.1%) and 97 female (46.8%) with a median age of 61.4 years (range 8-92 years). Overall, 489 patients (70.2%) were positive patients. The flowchart of the selection process of patients involved in the study and characteristics of the patients with negative CE are showed in Figure 1 and Table 1 respectively.

| Variables | Total patients | Negative for rebleeding | Rebleeding patients |

| n | 207 | 173 | 34 |

| Age (yr) | 56.8 | 56.8 | 57.1 |

| Sex (M/F) | 110/97 | 70/59 | 22/12 |

| Obscure-overt bleeding | 157 | 121 | 2 |

| Obscure-occult bleeding | 50 | 52 | 32 |

| Median Hb level | 8.2 | 8.8 | 8.2 |

| OAT/LMWH | 36 | 32 | 4 |

| Rebleeding time | |||

| At 10 mo of follow-up | 28 | ||

| At 24 mo of follow-up | 34 |

The median follow-up for all patients closely monitored for rebleeding was 24 mo (range 12-36 mo). Clinical recurrence of bleeding was observed during follow-up in 34 (16.4%) out of 207 patients with CE “negative for bleeding”. In details, 2 out of 34 patients had a new episode of melena, otherwise 32 patients had a recurrence of obscure occult bleeding with anemia and positive fecal occult blood test.

A Meckel diverticulum and a gastrointestinal stromal tumor were respectively diagnosed in the two patients presenting a new episode of obscure overt bleeding. In the group of 32 patients affected by a recurrence of obscure occult bleeding, the cause was undiagnosed in 13 cases (40.6%), whereas an extra-intestinal disease was diagnosed in 11/32 (34.3%) patients, a parasitic infestation in 3/32 (9.37%) and the chronic use of NSAIDs was indicated as the probable cause of the recurrence of bleeding in 5/32 (15.62%) patients. Moreover, we note that 2 out of 34 (5.8%) patients with negative CE and episodes of early rebleeding were receiving chronic therapy with oral anticoagulation, at 10 mo of follow-up.

The results of univariate and multivariate analysis about factors associated with rebleeding in patients with negative CE and reccurence re-bleeding are summarized in Table 2. Patients with OGIB and negative CE have a low percentage of probability of rebleeding (34/207). The statistical analysis of our data shows that the age of onset of the first episode of bleeding < 65 years and the type of bleeding (melena) are the only factors that statistically significantly influence the risk of re-bleeding (OR = 2.6703, 95%CI: 1.1651-6.1202, P = 0.0203; OR = 4.7718, 95%CI: 1.9739-11.5350, P = 0.0005) (Table 3). Other parameters considerated during our survey such as gender, number of blood transfusions, hemoglobin level, intake of anticoagulants, number of hospitalizations didn’t show a statistically significant correlation with rebleeding episodes. The final diagnosis and treatment of these patients are summarized in Table 3.

| Variables | No rebleeding | Rebleeding | P value | Odds ratio | 95%CI | P value |

| Patients | 173 | 34 | - | |||

| Sex (M/F) | 88/85 | 22/12 | 0.1403 | 1.84471 | 0.8175-4.16251 | 0.14031 |

| Age < 65 yr | 23 (67.6) | 89 (51.4) | 0.0838 | 2.6703 | 1.1651-6.1202 | 0.0203 |

| CE indications (melena) | 77 (44.5) | 26 (76.5) | 0.0006 | 4.7718 | 1.9739-11.5358 | 0.0005 |

| Blood transfusion | 64 (36.9) | 14 (41.2) | 0.6463 | |||

| Hb < 8 g/dL | 48 (27.7) | 14 (41.2) | 0.1189 | 2.0064 | 0.8891-4.5274 | 0.0935 |

| Use of FANS | 30 (17.3) | 5 (14.7) | 0.7085 | |||

| Oral anticoagulant therapy | 13 (7.5) | 4 (11.9) | 0.4104 | |||

| Hospitalizations (n) | 62 (35.8) | 14 (41.2) | 0.5559 |

| Type of rebleeding | n | Final diagnosis | Treatment |

| Obscure overt bleeding | 2 | Surgery | |

| Extraluminal GIST | |||

| Meckel’s diverticulum | |||

| Obscure occult bleeding | 32 | ||

| 13 | Causes not found | SR | |

| 5 | Myelodisplastyc syndrome | MT | |

| 3 | Uterine fibroma | Surgery | |

| 1 | Metastatic breast cancer | Surgery + MT | |

| 3 | Giardia lamblia infection | MT | |

| 5 | Chronic use of NSAID | ||

| 2 | Erosive gastritis | MT |

The patients “negative for rebleeding” with CE negative didn’t need a hospital admission at the time of rebleeding and no blood transfusions were required.

Regarding CE “positive” patients, clinical rebleeding was observed in 221 out of 489 (45.1%) patients. Rebleeding rate was 16.4% vs 45.1% (χ2 test, P = 0.00001). The sensitivity, specificity, and PPV and NPV were 93.8%, 100%, 100%, 80.1%, respectively. Most rebleedings occurred within the first 12 mo after the CE examinations (18/34; 52.9%).

Despite the wide diagnostic yield of CE compared to conventional diagnostic techniques, the impact of this relatively new investigation on patient outcome remains poorly defined. In particular, few CE studies used long-term rebleeding as the primary outcome. In this study, we determined the long-term clinical outcome and characteristics of patients with OGIB after negative CE. As reported previously[22,23,28,29], CE could not identify all bleeding lesions in patients with OGIB. Up to 36.7% of patients in this study had a negative CE despite overt clinical bleeding at presentation. Notably, this group of patients with negative CE had a low (19.8%) rebleeding rate in a more than 1 year follow-up. The rebleeding rate was significantly lower in patients with negative CE than in cases with positive CE. Moreover, considering the group of patients with negative CE, chronic therapy with oral anticoagulation and NSAIDs seems to be related to a higher risk of rebleeding. In accordance with our findings, Neu et al[30] found that rebleeding occured in 20% of patients with negative CE after a median follow-up of 13 mo. In a more recent study Lorenceau-Savale et al[31] showed as in 35 patients with a history of OGIB and negative CE and a minimum follow-up duration of one year (median: 15.9 mo) eight patients presented a recurrence of bleeding, with an overall rebleeding rate of 23%. Four women with recurrence before new investigations. In the four remaining patients, repeat endoscopy work-ups after negative CE were performed and revealed previously missed lesions with bleeding potential, mainly in the stomach. Overall, 13 patients, with or without rebleeding, had repeated endoscopy work-ups after a negative CE, leading to a definitive diagnosis in nine patients, with lesions located in the stomach and colon in eight of them.

Since the patients with OGIB and a negative CE had a low rate of rebleeding, further interventions or investigations could be deferred until clinical rebleeding occurs. In these cases, after ruling out a gastrointestinal lesions as causes of the recurrence of bleeding after the execution of a work-out negative for gastrointestinal bleeding properly done by following the guidelines proposed by AGA, the search for causes of obscure bleeding outside of the digestive system should be “necessarily” done.

Otherwise, patients with positive CE had a significantly higher rebleeding rate on long-term follow-up. Recently, Kim et al[32] performed CE in 125 patients with OGIB. The complete visualization of the small bowel was achieved in 93 patients (74.4%). Of the 63 patients (50.4%) with negative CE results, 60 patients did not receive any further specific treatment for OGIB. Rebleeding episodes were observed in 16 out of 60 patients (26.7%). Substantial rebleeding events were observed with similar frequency both after negative CE without subsequent treatment (26.7%) and after positive CE without specific treatment (21.2%) (P = 0.496). The Authors conclude that in some cases despite a negative CE, approach such as double balloon endoscopy (DBE) should be considered as complementary procedures for further evaluation.

Our study confirms, also in accordance with Lai et al[33] that patients with positive CE have a high rebleeding rate, a longer hospital stay and require more units of blood transfused than those with negative CE; in accordance with Kim et al[32], the device-assisted enteroscopy (DBE or single-balloon enteroscopy) could be helpful in patients with a high index of suspicion for small bowel pathologies and with a high risk of rebleeding and negative CE.

The limits of the present study are discussed below. First, the lack of a gold standard for small bowel diagnosis limits the accuracy in the determination of CE performance. It is highly possible that some lesions may be missed despite an extensive investigation. However, unlike many published studies, we used long-term clinical rebleeding instead of small bowel lesions as the primary end point for the determination of CE performance. It may be interesting to determine, in future studies, whether the use of the recently available methods of device-assisted enteroscopy[34,35] and their future technical developments could overcome this problem. Secondly, all our “negative for rebleeding” patients refused to undergo further endoscopic examinations for various reasons. Third, we only recruited patients with “genuine” OGIB, meaning that these patients had undergone multiple upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopies by experienced endoscopists to rule out other possible sources of bleeding. Consequently, these results could not necessarily be generalized to all patients with suspected small bowel bleeding.

In conclusion, even if additional studies are warranted to confirm these results, we found that in a follow-up of a mean 24 mo, patients with OGIB and negative CE had a significative low long-term rebleeding rate, suggesting that further invasive investigations could be deferred and may not be necessary in this group of patients. Only an accurate and careful clinical observation can help us to identify false negative patients at CE.

Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) remains a major clinical challenge to gastroenterologists. Many instances of OGIB originate from the small bowel, which is beyond the reach of an ordinary endoscope, including an esophagogastroduodenoscope and colonoscope.

The scene was recently revolutionized by the availability of capsule endoscopy (CE), which is noninvasive and well tolerated by patients. In this study the authors assess the rate of recurrent bleeding of the small bowel in patients with obscure bleeding already undergone CE with negative results.

Recent reports have highlighted the importance of CE in the clinical assessment of patients with presumed small bowel diseases. For OGIB, CE is recommended as an investigation modality for the detection of a bleeding source after traditional endoscopy. However, even after full evaluation of the small bowel, CE is not able to highlight the bleeding focus. In the present study, they sought to reveal the outcomes after negative CE for OGIB and the risk factors associobscure bleeding already undergone CE with negative results.

By understanding the value of negative CE and the value of long-term of follow-up in these patients. Patients with OGIB and negative CE had a significantly lower rebleeding rate, and further invasive investigations can be deferred. However, when a confirmatory diagnosis is made by CE study, specific treatments can be applied according to the diagnosis.

CE is the most innovative and less invasive resource for the study of the small bowel playing an essential role in the diagnosis of small bowel diseases until now disregarded and the setting of therapeutic decisions.

The authors retrospectively present information on 696 patients who underwent CE for OGIB with negative standard tests. They excluded for detailed analysis 489 patients an instead concentrated on outcome in 207 patients in whom the CE proved negative. They found a statistically lower rebleed rate over a median of 24 mo in these CE negative patients compared to the CE positive group. The CE-patients had various other explanations found later in 60%. No explanation was found in the rest. In multivariate analysis age < 65 years and melena on presentation were found to be predictors of rebleed in CE-patients.

| 1. | Kornbluth A, Legnani P, Lewis BS. Video capsule endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease: past, present, and future. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:278-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bardan E, Nadler M, Chowers Y, Fidder H, Bar-Meir S. Capsule endoscopy for the evaluation of patients with chronic abdominal pain. Endoscopy. 2003;35:688-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kraus K, Hollerbach S, Pox C, Willert J, Schulmann K, Schmiegel W. Diagnostic utility of capsule endoscopy in occult gastrointestinal bleeding. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2004;129:1369-1374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Petroniene R, Dubcenco E, Baker JP, Warren RE, Streutker CJ, Gardiner GW, Jeejeebhoy KN. Given capsule endoscopy in celiac disease. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2004;14:115-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | de Franchis R, Rondonotti E, Abbiati C, Beccari G, Merighi A, Pinna A, Villa E. Capsule enteroscopy in small bowel transplantation. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:728-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | de Mascarenhas-Saraiva MN, da Silva Araújo Lopes LM. Small-bowel tumors diagnosed by wireless capsule endoscopy: report of five cases. Endoscopy. 2003;35:865-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Delvaux M. Capsule endoscopy in 2005: facts and perspectives. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:23-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Scapa E, Jacob H, Lewkowicz S, Migdal M, Gat D, Gluckhovski A, Gutmann N, Fireman Z. Initial experience of wireless-capsule endoscopy for evaluating occult gastrointestinal bleeding and suspected small bowel pathology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2776-2779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Voderholzer WA, Beinhoelzl J, Rogalla P, Murrer S, Schachschal G, Lochs H, Ortner MA. Small bowel involvement in Crohn’s disease: a prospective comparison of wireless capsule endoscopy and computed tomography enteroclysis. Gut. 2005;54:369-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fireman Z, Mahajna E, Broide E, Shapiro M, Fich L, Sternberg A, Kopelman Y, Scapa E. Diagnosing small bowel Crohn’s disease with wireless capsule endoscopy. Gut. 2003;52:390-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Herrerías JM, Caunedo A, Rodríguez-Téllez M, Pellicer F, Herrerías JM. Capsule endoscopy in patients with suspected Crohn’s disease and negative endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2003;35:564-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Appleyard M, Fireman Z, Glukhovsky A, Jacob H, Shreiver R, Kadirkamanathan S, Lavy A, Lewkowicz S, Scapa E, Shofti R. A randomized trial comparing wireless capsule endoscopy with push enteroscopy for the detection of small-bowel lesions. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1431-1438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Costamagna G, Shah SK, Riccioni ME, Foschia F, Mutignani M, Perri V, Vecchioli A, Brizi MG, Picciocchi A, Marano P. A prospective trial comparing small bowel radiographs and video capsule endoscopy for suspected small bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:999-1005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 565] [Cited by in RCA: 519] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ell C, Remke S, May A, Helou L, Henrich R, Mayer G. The first prospective controlled trial comparing wireless capsule endoscopy with push enteroscopy in chronic gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2002;34:685-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 435] [Cited by in RCA: 410] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mylonaki M, Fritscher-Ravens A, Swain P. Wireless capsule endoscopy: a comparison with push enteroscopy in patients with gastroscopy and colonoscopy negative gastrointestinal bleeding. Gut. 2003;52:1122-1126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 342] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Marmo R, Rotondano G, Piscopo R, Bianco MA, Cipolletta L. Meta-analysis: capsule enteroscopy vs. conventional modalities in diagnosis of small bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:595-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Triester SL, Leighton JA, Leontiadis GI, Fleischer DE, Hara AK, Heigh RI, Shiff AD, Sharma VK. A meta-analysis of the yield of capsule endoscopy compared to other diagnostic modalities in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2407-2418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 433] [Cited by in RCA: 421] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mata A, Bordas JM, Feu F, Ginés A, Pellisé M, Fernández-Esparrach G, Balaguer F, Piqué JM, Llach J. Wireless capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: a comparative study with push enteroscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:189-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Adler DG, Knipschield M, Gostout C. A prospective comparison of capsule endoscopy and push enteroscopy in patients with GI bleeding of obscure origin. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:492-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Saurin JC, Delvaux M, Gaudin JL, Fassler I, Villarejo J, Vahedi K, Bitoun A, Canard JM, Souquet JC, Ponchon T. Diagnostic value of endoscopic capsule in patients with obscure digestive bleeding: blinded comparison with video push-enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2003;35:576-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Pennazio M, Santucci R, Rondonotti E, Abbiati C, Beccari G, Rossini FP, De Franchis R. Outcome of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after capsule endoscopy: report of 100 consecutive cases. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:643-653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 637] [Cited by in RCA: 606] [Article Influence: 27.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rastogi A, Schoen RE, Slivka A. Diagnostic yield and clinical outcomes of capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:959-964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Swain P, Fritscher-Ravens A. Role of video endoscopy in managing small bowel disease. Gut. 2004;53:1866-1875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Raju GS, Gerson L, Das A, Lewis B. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute medical position statement on obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1694-1696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Mishkin DS, Chuttani R, Croffie J, Disario J, Liu J, Shah R, Somogyi L, Tierney W, Song LM, Petersen BT. ASGE Technology Status Evaluation Report: wireless capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:539-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Apostolopoulos P, Liatsos C, Gralnek IM, Giannakoulopoulou E, Alexandrakis G, Kalantzis C, Gabriel P, Kalantzis N. The role of wireless capsule endoscopy in investigating unexplained iron deficiency anemia after negative endoscopic evaluation of the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract. Endoscopy. 2006;38:1127-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Galen RS, Gambino SR. Beyond normality: the predictive value and efficiency of medical diagnoses. New York: John Wiley & Sons Ine 1975; . |

| 28. | Delvaux M, Fassler I, Gay G. Clinical usefulness of the endoscopic video capsule as the initial intestinal investigation in patients with obscure digestive bleeding: validation of a diagnostic strategy based on the patient outcome after 12 months. Endoscopy. 2004;36:1067-1073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Saurin JC, Delvaux M, Vahedi K, Gaudin JL, Villarejo J, Florent C, Gay G, Ponchon T. Clinical impact of capsule endoscopy compared to push enteroscopy: 1-year follow-up study. Endoscopy. 2005;37:318-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Neu B, Ell C, May A, Schmid E, Riemann JF, Hagenmüller F, Keuchel M, Soehendra N, Seitz U, Meining A. Capsule endoscopy versus standard tests in influencing management of obscure digestive bleeding: results from a German multicenter trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1736-1742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lorenceau-Savale C, Ben-Soussan E, Ramirez S, Antonietti M, Lerebours E, Ducrotté P. Outcome of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after negative capsule endoscopy: results of a one-year follow-up study. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010;34:606-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kim JB, Ye BD, Song Y, Yang DH, Jung KW, Kim KJ, Byeon JS, Myung SJ, Yang SK, Kim JH. Frequency of rebleeding events in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding with negative capsule endoscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:834-840. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 33. | Lai LH, Wong GL, Chow DK, Lau JY, Sung JJ, Leung WK. Long-term follow-up of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after negative capsule endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1224-1228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Yamamoto H, Sekine Y, Sato Y, Higashizawa T, Miyata T, Iino S, Ido K, Sugano K. Total enteroscopy with a nonsurgical steerable double-balloon method. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:216-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 896] [Cited by in RCA: 867] [Article Influence: 34.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Matsumoto T, Esaki M, Moriyama T, Nakamura S, Iida M. Comparison of capsule endoscopy and enteroscopy with the double-balloon method in patients with obscure bleeding and polyposis. Endoscopy. 2005;37:827-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewers Bordas JM, Kopacova M, Szilagyi A S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN