Published online Jul 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i25.4087

Revised: May 15, 2013

Accepted: May 18, 2013

Published online: July 7, 2013

Processing time: 125 Days and 1.3 Hours

Gastrointestinal arterio-venous malformations are a known cause of gastrointestinal bleeding. We present a rare case of persistent rectal bleeding due to a rectal arterio-portal venous fistula in the setting of portal hypertension secondary to portal vein thrombosis. The portal hypertension was initially surgically treated with splenectomy and a proximal splenorenal shunt. However, rectal bleeding persisted even after surgery, presenting us with a diagnostic dilemma. The patient was re-evaluated with a computed tomography mesenteric angiogram which revealed a rectal arterio-portal fistula. Arterio-portal fistulas are a known but rare cause of portal hypertension, and possibly the underlying cause of continued rectal bleeding in this case. This was successfully treated using angiographic localization and super-selective embolization of the rectal arterio-portal venous fistula via the right internal iliac artery.The patient subsequently went on to have a full term pregnancy. Through this case report, we hope to highlight awareness of this unusual condition, discuss the diagnostic workup and our management approach.

Core tip: We present a rare case of persistent rectal bleeding due to a rectal arterio-portal venous fistula, in the setting of portal hypertension. Through this case report, we hope to highlight awareness of this unusual condition, and discuss the diagnostic workup and our subsequent management. We believe that this is the first of such cases reported in the literature.

- Citation: Yap HY, Lee SY, Chung YFA, Tay KH, Low ASC, Thng CH, Madhavan K. Rectal arterio-portal fistula: An unusual cause of persistent bleeding per rectum following a proximal spleno-renal shunt. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(25): 4087-4090

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i25/4087.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i25.4087

Arterio-venous malformations occurring in the gastrointestinal tract are a known cause of gastro-intestinal bleeding and can often be missed especially in the presence of other pathology. They can lead to persistent symptoms if left undiagnosed and untreated. We present a patient who had portal vein thrombosis, portal hypertension and continued to have rectal bleeding in spite of a patent spleno renal shunt to highlight awareness of this unusual condition.

A 33-year-old Chinese lady presented with multiple episodes of haematemesis when she was nine years old.She was seen in a secondary hospital and diagnosed to have portal hypertension secondary to portal vein thrombosis (PVT), a possible sequelae of a neonatal umbilical infection. The portal hypertension resulted in her having episodes of bleeding esophageal varices that were treated endoscopically during her childhood years. On clinical examination, she had splenomegaly but no stigmata of chronic liver disease. Investigations revealed that she did not have any liver cirrhosis or prothrombotic disorders. Liver function tests were normal. Radiological investigations confirmed the PVT and splenomegaly. More than twenty years after her initial diagnosis, she started to develop intermittent episodes of rectal bleeding which was attributed to rectal varices. She was anaemic (haemoglobin level 7.0 g/dL) and required intermittent blood transfusions for her symptoms. Her splenomegaly led to consumption thrombocytopenia (platelet levels ranged from 74-103 × 109 g/L) and she subsequently sought a second opinion at a tertiary centre, after much investigation including a contrast enhanced computed tomography scan, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and a colonoscopy.

Pre-operative investigations were reviewed and showed PVT, splenomegaly and a dilated inferior mesenteric vein all the way down to the pelvis. Colonoscopy reported that there were large rectal varices. Based on these investigations, we presumed that the rectal varices were a result of left sided portal hypertension with the pressure transmitted down the inferior mesenteric vein, and thus performed a splenectomy and an end-to-side proximal splenorenal shunt for portal decompression.

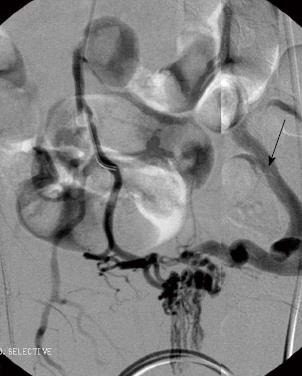

After surgery, the patient continued to have rectal bleeding during her follow-up. A flexible sigmoidoscopy was performed and this revealed almost circumferentially dilated pulsatile submucosal vessels at the lower rectum. These were not reported in the colonoscopy that the patient underwent previously in the secondary hospital. A multiphasic computed tomography mesenteric angiogram confirmed a rectal arterio-venous fistula. On the arterial phase of the scan, there was evidence of arterio-venous shunting as evidenced by the dilated superior rectal vein draining into the superior mesenteric vein, with arterial feeders from the internal iliac arteries (Figure 1). A diagnostic catheter angiogram was performed to confirm the complexity of the feeder vessels and assess the potential collateral damage to rectal mucosa that could occur with angioembolisation. This revealed that there were two major arterial feeders arising from the anterior division of the internal iliac arteries on both sides which were supplying the arterio-portal fistula. There was a single tortuous drainage vein into the inferior mesenteric vein (Figure 2).

A super selective angioembolisation of the arterio-portal fistula was performed via a left common femoral artery access. The EV3 Apollo microcatheter (ev3 Endovascular Inc., Plymouth, MA, United States) was introduced and advanced into the arterio-portal fistula nidus and embolisation performed using 2cc of Onyx 18 embolic agent (ev3 Endovascular Inc., Plymouth, MA, United States). Completion angiograms via both internal iliac arteries showed successful obliteration of the arterio-portal fistula with cessation of arterio-portal shunting (Figure 3).

Post procedure, clinical examination and a repeat flexible sigmoidoscopy confirmed that there was no rectal ischemia. However, the patient complained of anal pain and further rectal bleeding, although the quantity of bleeding was much reduced. On clinical examination, she was found to have an anal fissure at 3 o’clock position, possibly as a result of the embolisation. This was initially treated with topical methods but did not resolve her symptoms and thus she underwent a lateral anal sphincterotomy. Since surgery, she has successfully delivered a child after a full-term pregnancy and her haemoglobin (12.0 g/dL) and platelet levels have returned to normal.

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) in the gastrointestinal tract are a known cause of gastrointestinal bleeding, and are usually difficult to diagnose. In the literature, it has been reported that the highest frequency of gastrointestinal AVMs occur in the right sided colon[1]. Arteriovenous malformations in the rectum are rare and it is often difficult to distinguish between bleeding from the AVM and bleeding from haemorrhoids, leading to diagnostic delays and even unnecessary procedures being performed for haemorroids[2].

Arterio-portal fistulas are a type of arteriovenous malformations defined as abnormal communications between the systemic arteries and the portal circulation[3]. They can be congenital or acquired. Congenital causes include arteriovenous malformations, ruptured aneurysms and hereditary telangiectatic diseases where there might be multiple arterio-portal fistulas present[4-7]. The majority of them are a result of penetrating or blunt trauma to the vessels which can be iatrogenic[8]. Most commonly, arterio-portal fistulas originate from the celiac or splanchnic circulation in particular the hepatic artery or splenic artery due to their close proximity to the portal and splenic veins. Rarely, they can be found to arise from the superior mesenteric or inferior mesenteric arteries[3].In our patient, the arterio-portal fistula arose from the internal iliac arteries and this is believed to be the first such case reported in the literature.

Portal vein thrombosis is a known cause of extra-hepatic presinusoidal portal hypertension. In neonates, this can be caused by umbilical infection, often as a result of umbilical vein catheterisation. The infection spreads along the left portal vein to the main portal vein causing thrombosis[8]. Due to the increase in portal resistance, collaterals arise from the high pressure veins in the portal system to the low pressure veins in the systemic circulation. The reversal of blood flow towards the systemic venous circulation leads to formation of varices at the oesophago-gastric region, along the falciform ligament at the umbilicus, in the retroperitoneum via the veins of Retzius and at the anorectal region where the superior haemorrhoidal veins decompress into the middle and inferior haemorroidal veins of the systemic circulation. Our patient presented with bleeding esophageal varices at an early age and this lead to her diagnosis of PVT. The leading cause of mortality in portal hypertension is bleeding esophageal varices[9]. Anorectal varices rarely bleed, likely due to the rich plexus of veins around the rectum which shunts away most of the blood.

In our patient, we offer two possibilities to account for her condition. The first is that she has a congenital pre-existing arterio-portal fistula between the rectal artery and the haemorrhoidal veins. However, when the patient first presented with rectal bleeding in the setting of portal hypertension, the most likely diagnosis of bleeding ano-rectal varices was made and she was treated with the aim of reducing her portal pressures, which was the presumed cause of the ano-rectal varices. In retrospect, this was a wrong postulation. The rectal bleeding did not resolve despite the splenorenal shunt and only on further investigations did we discover the arterio-portal fistula which had initially masqueraded as bleeding ano-rectal varices. Awareness of this entity as a possible differential diagnosis for bleeding ano-rectal varices is important. Initial investigation with a dynamic computed tomography scan with arterial and portal venous phase would have brought the diagnosis to light.

The second possibility is that the arterio-portal fistula was formed due to unintended or unnoticed trauma to the rectal wall. The left sided portal hypertension led to the formation of dilated portal vasculature in the rectum.These rectal varices are in close proximity to the branches of the arteries supplying the rectum, like the middle rectal artery in this case. An episode of unsuspecting trauma to the rectal wall possibly during defecation, led to the formation of the abnormal vascular communication between the middle rectal artery and the rectal varices, propagating the formation of an arterio-portal fistula

Multiphasic contrast enhanced computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis helped to clinch the diagnosis of the arterio-portal fistula in this case, as contrast was seen on the draining dilated superior rectal vein in the arterial phase of the scan. This distinguishes it from a simple rectal bleeding secondary to rectal varices.In the setting of portal hypertension, awareness of the possible diagnoses is critical.

In the era prior to interventional radiology, arterio-portal fistulas were usually treated by open surgical excision. With the advent of super-selective angiographic catheterisation, embolisation is now the definitive treatment of choice for patients if the expertise is available[3].Inadequate imaging especially in the setting of presumed portal hypertension has led to the delayed diagnosis of this arterio-portal fistula and local transanal treatment could have been catastrophic. Endoscopic ablation of the nidus of dilated collaterals in the rectum using sclerosant or banding could have led to massive haemorrhage from high pressure arterial bleeding if it was simply treated as for rectal varices following portal decompression.

In conclusion, arterio-portal fistulas are a known cause of portal hypertension and can also cause a diagnostic dilemma in the setting of portal hypertension. Angiographic embolisation is the treatment of choice and this can be achieved with minimal morbidity.

| 1. | Höchter W, Weingart J, Kühner W, Frimberger E, Ottenjann R. Angiodysplasia in the colon and rectum. Endoscopic morphology, localisation and frequency. Endoscopy. 1985;17:182-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hayakawa H, Kusagawa M, Takahashi H, Okamura K, Kosaka A, Mizumoto R, Katsura K. Arteriovenous malformation of the rectum: report of a case. Surg Today. 1998;28:1182-1187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Vauthey JN, Tomczak RJ, Helmberger T, Gertsch P, Forsmark C, Caridi J, Reed A, Langham MR, Lauwers GY, Goffette P. The arterioportal fistula syndrome: clinicopathologic features, diagnosis, and therapy. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1390-1401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Montejo Baranda M, Perez M, De Andres J, De la Hoz C, Merino J, Aguirre C. High out-put congestive heart failure as first manifestation of Osler-Weber-Rendu disease. Angiology. 1984;35:568-576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Roman CF, Cha SD, Incarvito J, Cope C, Maranhao V. Transcatheter embolization of hepatic arteriovenous fistula in Osler-Weber-Rendu disease--a case report. Angiology. 1987;38:484-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kahn T, Reiser M, Gmeinwieser J, Heuck A. The Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, type IV, with an unusual combination of organ malformations. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1988;11:288-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nikolopoulos N, Xynos E, Vassilakis JS. Familial occurrence of hyperdynamic circulation status due to intrahepatic fistulae in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Hepatogastroenterology. 1988;35:167-168. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Sheila S, James D. The Portal Venous System and Portal Hypertension. Diseases of the Liver and Biliary Systems. 11th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing 2002; 163. |

| 9. | Collins JC, Sarfeh IJ. Surgical management of portal hypertension. West J Med. 1995;162:527-535. [PubMed] |

P- Reviewers HartlebM, Ho SB, KupcinskasL, Panduro A S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY