Published online Jun 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i23.3608

Revised: April 4, 2013

Accepted: April 9, 2013

Published online: June 21, 2013

Processing time: 121 Days and 3.7 Hours

AIM: To clarify the diagnostic values of hematoxylin and eosin (HE), D2-40, CD31, CD34, and HHV-8 immunohistochemical (IHC) staining in gastrointestinal Kaposi’s sarcoma (GI-KS) in relation to endoscopic tumor staging.

METHODS: Biopsy samples (n = 133) from 41 human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients were reviewed. GI-KS was defined as histologically negative for other GI diseases and as a positive clinical response to KS therapy. The receiver operating characteristic area under the curve (ROC-AUC) was compared in relation to lesion size, GI location, and macroscopic appearances on endoscopy.

RESULTS: GI-KS was confirmed in 84 lesions (81.6%). Other endoscopic findings were polyps (n = 9), inflammation (n = 4), malignant lymphoma (n = 4), and condyloma (n = 2), which mimicked GI-KS on endoscopy. ROC-AUC of HE, D2-40, blood vessel markers, and HHV-8 showed results of 0.83, 0.89, 0.80, and 0.82, respectively. For IHC staining, the ROC-AUC of D2-40 was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than that of HE staining only. In the analysis of endoscopic appearance, the ROC-AUC of HE and IHC showed a tendency toward an increase in tumor staging (e.g., small to large, patches, and polypoid to SMT appearance). D2-40 was significantly (P < 0.05) advantageous in the upper GI tract and for polypoid appearance compared with HE staining.

CONCLUSION: The diagnostic value of endothelial markers and HHV-8 staining was found to be high, and its accuracy tended to increase with endoscopic tumor staging. D2-40 will be useful for complementing HE staining in the diagnosis of GI-KS, especially in the upper GI tract and for polypoid appearance.

Core tip: Diagnosis of gastrointestinal Kaposi sarcoma (GI-KS) is important because treatment specifics depend on the extent of the disease. Endoscopic biopsy is a definitive diagnostic method for GI-KS, but its diagnostic accuracy has not been fully studied. In the current study, receiver operating characteristic area under the curve of hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining, lymphatic and blood vessel endothelial cell markers, and HHV-8 was found to be high (> 0.80), and its accuracy tended to increase with endoscopic tumor staging. D2-40 will be useful for complementing HE staining in the diagnosis of GI-KS, especially in the upper GI tract and for polypoid appearance.

- Citation: Nagata N, Igari T, Shimbo T, Sekine K, Akiyama J, Hamada Y, Yazaki H, Ohmagari N, Teruya K, Oka S, Uemura N. Diagnostic value of endothelial markers and HHV-8 staining in gastrointestinal Kaposi sarcoma and its difference in endoscopic tumor staging. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(23): 3608-3614

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i23/3608.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i23.3608

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a rare cancer that was highly prevalent in the early stages of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) endemic[1]. Although the rate of KS has shown a marked reduction since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART)[1-3], KS remains the most common malignancy in patients with AIDS[4].

KS primarily involves the skin but can also involve the viscera[5-7]. Because the need for treatment and choice of treatment depend on visceral involvement[1-3,8-11], diagnosis of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, a common site of visceral involvement[11-13], is important. Definitive diagnosis of GI-KS requires endoscopic biopsy[6,7,14-16], but GI-KS often presents on endoscopy with submucosal or small protruded appearance[17,18], which can lead to false-negative biopsy results[14-16].

Recently, immunohistochemical (IHC) staining with D2-40, CD31, CD34, and HHV-8 has been reported as useful for distinguishing cutaneous KS from other diseases[19-28]. However, no IHC studies have reported on the utility of KS diagnosis in the GI tract. In addition, it is not known how well such staining methods provide additive effects compared with HE staining alone.

With regard to the diagnosis of cutaneous KS, there may be subtle differences in the staining patterns for endothelial markers between different histologic stages (patch, plaque, and nodular) of KS[19,21,22,25]. In the GI tract, KS has various macroscopic presentations[13-15,17,18,29] and KS may affect any part of the GI tract[7,13,14,17,18]. However, the effect of IHC-positive staining in the diagnosis of GI-KS on the basis of lesion appearance has not been fully investigated.

The purpose of this study was to clarify the diagnostic value of IHC staining in the diagnosis of GI-KS and to assess the difference in accuracy between HE and IHC staining in relation to endoscopic tumor staging.

We retrospectively reviewed histologic slides from 103 consecutive lesions for which IHC staining was performed between 2006 and 2012 at the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (NCGM). Lesions were obtained from 41 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients who had not received anti-KS therapy. The institutional review board at NCGM approved this study.

Sexual behavior was classified subjects into two groups: men who have sex with men (MSM); and heterosexual. CD4+ cell counts and HIV-RNA viral load (VL) determined by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were reviewed within 1 mo of endoscopy. A positive result for real-time HIV-RNA was defined as ≥ 40 copies/mL. History of HAART was collected from medical records prior to endoscopy. GI symptoms were assessed by the physician who interviewed each patient. Those without GI symptoms and negative screening endoscopy were considered to be symptom-free.

Confirmed GI-KS lesions were defined as those that fulfilled with following criteria. (1) Histologically negative biopsy for other GI diseases; (2) A positive response to KS therapy (HAART or systemic therapy of liposomal anthracycline); and (3) partial or complete resolution was confirmed on follow-up endoscopy after KS therapy (Figure 1). We usually perform endoscopy after 1 mo, 2 mo, or 6 mo of KS therapy to evaluate GI-KS regression.

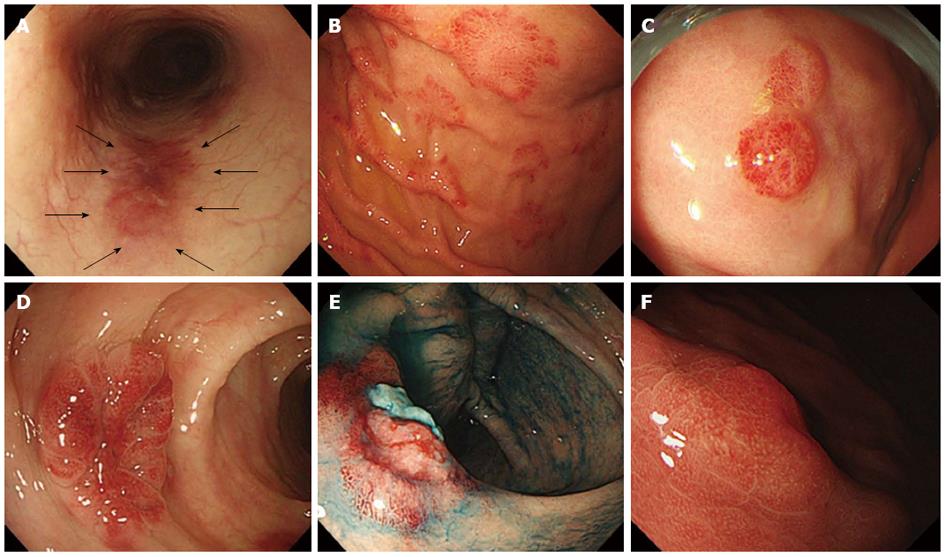

All 103 lesions were suspected to be GI-KS on endoscopy, as they exhibited properties such as reddish with patches, polypoid appearance, submucosal tumor (SMT)-like lesions, and ulcerative SMT, as previously reported[13-15,17,18,29]. Therefore, IHC staining in addition to HE staining was performed.

Endoscopic images were taken using a high-resolution scope (model GFH260, CFH260AI; Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan) in all patients. We performed a biopsy using biopsy forceps (FB-240U, FB230-K, Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan).

Size (< 10 mm or ≥ 10 mm), GI location, and macroscopic findings were assessed endoscopically. Locations of GI involvement were classified as upper GI (esophagus, stomach, and duodenum) and lower GI (ileum, colon, and rectum).

Macroscopic findings were evaluated as the presence of reddish mucosa with patches (Figure 2A), polypoid lesions (Figure 2B), submucosal tumor (SMT) (Figure 2C), and ulcerative SMT (Figure 2D), as previously reported[13-15,17,18,29]. Ulceration was defined endoscopically as a distinct, visible crater > 5 mm in diameter with a slough base.

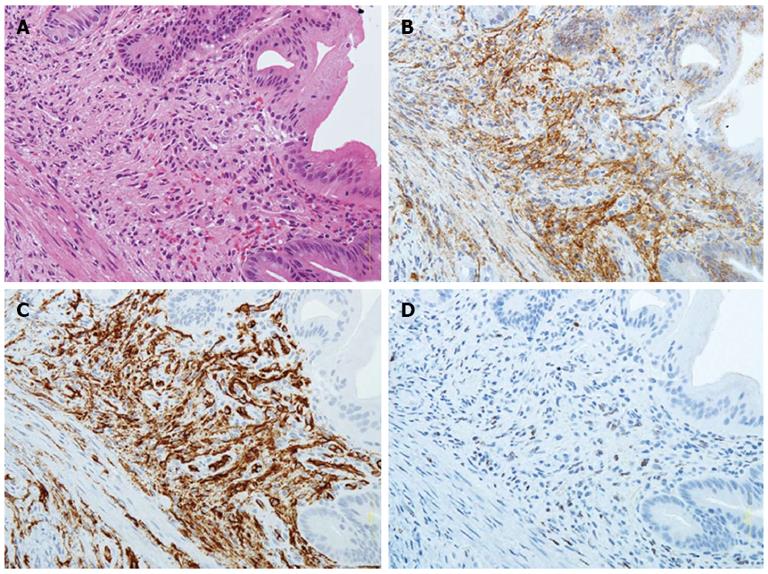

The presence of proliferating spindle cells with vascular channels filled with blood cells (Figure 3A) from biopsy specimens was evaluated with HE staining by an investigator blinded to IHC staining results. IHC staining for the lymphatic vessel endothelial cell marker D2-40 (Dako North America, Carpentaria, CA) (Figure 3B) and the blood vessel endothelial cell markers CD31 (Dako North America) or CD34 (Dako North America) (Figure 3C), and the use of the mouse monoclonal antibody against HHV-8 LNA-1 (Novocastra Laboratories Ltd, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom) (Figure 3D), were also evaluated on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections as previously reported[19-28]. IHC slides were evaluated at × 200 and × 400 magnification by expert GI pathologists.

To elucidate the accuracy of HE and IHC staining for the diagnosis of GI-KS, the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratio (LR+ and LR-, respectively), and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC-AUC) were calculated and estimated with a 95%CI.

The difference of the ROC-AUC of the four specific stains (HE, D2-10, vessel markers, and HHV-8) was compared. Subgroup analysis was performed to identify differences in four specific stains according to gross appearances, and the ROC-AUC was compared in each group. ROC-AUC differences between HE staining and specific IHC staining in each groups were also compared.

Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant. All statistical analysis was performed using Stata version 10 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

All 41 HIV-infected patients were male and the HIV infection route was MSM in all cases. The median CD4 cell count (interquartile range; IQR) was 77 (33, 157) cells/mL and the median HIV viral load (IQR) was 48500 (< 40, 150000) copies/mL. There were 18 (43.9%) patients with a history of HAART. GI symptoms were noted in 10 patients (24.4%). No notable gastrointestinal bleeding or perforation, either spontaneously or after endoscopic biopsy, was noted.

Table 1 provides details on the definitive diagnosis of GI lesions. Of the 103 lesions, 84 (81.6%) were confirmed as GI-KS while the remainder were other GI lesions (19) consisted of hyperplastic polyps (8), fundic grand polyps (1), Helicobacter-associated gastritis (1), malignant lymphoma (4), anorectal condyloma (2), and non-specific colitis (3).

| Diagnosis | No. |

| GI-KS | 84 |

| Upper GI tract | 57 (67.9) |

| Esophagus | 7 (8.3) |

| Stomach | 38 (45.2) |

| Duodenum | 12 (14.3) |

| Lower GI tract | 27 (32.1) |

| Cecum | 8 (9.5) |

| Ascending colon | 1 (1.2) |

| Transverse colon | 2 (2.4) |

| Descending colon | 1 (1.2) |

| Sigmoid colon | 7 (8.3) |

| Rectum | 8 (9.5) |

| Non-KS lesion | 19 |

| Hyperplastic polyp | 8 |

| Fundic gland polyps | 1 |

| Helicobacter-associated gastritis | 1 |

| Malignant lymphoma | 4 |

| Anorectal condyloma | 2 |

| Non-specific colitis | 3 |

Sensitivity, specificity, LR+, LR-, and ROC-AUC of specific staining for the diagnosis of GI-KS are shown in Table 2. The ROC-AUC values of four specific stains (HE, D2-40, blood vessel marker, and HHV-8) were significantly different (P < 0.01) in the diagnosis of GI-KS (Table 2). The ROC-AUC of D2-40 staining was only significantly higher (P < 0.05) than that of HE staining (Table 2).

| KS/non-KS (84/19) | Sensitivity, % (95%CI) | Specificity, % (95%CI) | Positive LR (95%CI) | Negative LR (95%CI) | ROC area1 (95%CI) |

| HE | 70.2 (59.3-79.7) | 94.7 (74.0-99.9) | 9.33 (1.99-43.8)2 | 0.32 (0.23-0.46)2 | 0.83 (0.75-0.90) |

| (59/1) | |||||

| D2-40 | 77.4 (67.0-85.8) | 100 (82.4-100) | 30.8 (1.99-477)2 | 0.24 (0.16-0.35)2 | 0.89 (0.84-0.93)a |

| (65/0) | |||||

| Blood vessel marker | 81 (70.9- 88.7) | 78.9 (54.4- 93.9) | 3.85 (1.6-9.24) | 0.24 (0.15-0.40) | 0.80 (0.70-0.90) |

| (68/4) | |||||

| HHV-8 | 63.1 (51.9-73.4) | 100 (82.4-100) | 25.2 (1.62-391)2 | 0.38 (0.29-0.51)2 | 0.82 (0.76-0.87) |

| (53/0) |

The ROC-AUC of four specific stains showed a tendency toward an increase in tumor staging on endoscopy (e.g., small to large, flat, protruded, and SMT appearance) (Table 3). The ROC-AUC of blood vessel marker in polypoid appearance was extremely low compared with other lesions (Table 3).

| Subgroup | Specific stain | No. of lesions (KS/non-KS) | ROC-AUC (95%CI) | P value1 |

| Size | Size < 10 mm | 26/7 | ||

| HE | 14/0 | 0.77 (0.67-0.87) | ||

| D2-40 | 16/0 | 0.81 (0.71-0.90) | ||

| Blood vessel marker | 18/4 | 0.56 (0.34-0.78) | ||

| HHV-8 | 10/0 | 0.69 (0.60-0.79) | < 0.05 | |

| Size > 10 mm | 58/12 | |||

| HE | 45/1 | 0.85 (0.75-0.94) | ||

| D2-40 | 49/0 | 0.92 (0.88-0.97) | ||

| Blood vessel marker | 50/0 | 0.93 (0.89-0.98) | ||

| HHV-8 | 43/0 | 0.93 (0.89-0.98) | < 0.01 | |

| Location | Upper GI tract | 57/9 | ||

| HE | 36/0 | 0.82 (0.75-0.88) | ||

| D2-40 | 42/0 | 0.87 (0.81-0.93)a | ||

| Blood vessel marker | 44/4 | 0.66 (0.48-0.84) | ||

| HHV-8 | 36/0 | 0.82 (0.75-0.88) | < 0.01 | |

| Lower GI tract | 27/10 | |||

| HE | 23/1 | 0.88 (0.76-1.00) | ||

| D2-40 | 23/0 | 0.93 (0.86-0.99) | ||

| Blood vessel marker | 24/0 | 0.94 (0.88-1.00) | ||

| HHV-8 | 17/0 | 0.82 (0.72-0.91) | < 0.01 | |

| Macroscopic appearance | Patches | 23/4 | ||

| HE | 12/1 | 0.64 (0.37-0.90) | ||

| D2-40 | 14/0 | 0.80 (0.70-0.91) | ||

| Blood vessel marker | 15/0 | 0.83 (0.73-0.93) | ||

| HHV-8 | 8/0 | 0.67 (0.57-0.77) | < 0.01 | |

| Polypoid | 9/3 | |||

| HE | 5/0 | 0.78 (0.61-0.95) | ||

| D2-40 | 8/0 | 0.94 (0.84-1.00)a | ||

| Blood vessel marker | 8/3 | 0.44 (0.34-0.55)a | ||

| HHV-8 | 4/0 | 0.72 (0.55-0.89) | < 0.01 | |

| SMT | 37/7 | |||

| HE | 32/0 | 0.93 (0.88-0.99) | ||

| D2-40 | 33/0 | 0.95 (0.90-0.10) | ||

| Blood vessel marker | 33/1 | 0.88 (0.73-1.00) | ||

| HHV-8 | 30/0 | 0.91 (0.84-0.97) | 0.15 | |

| SMT with ulcer | 15/5 | |||

| HE | 10/0 | 0.83 (0.71-0.96) | ||

| D2-40 | 10/0 | 0.83 (0.71-0.96) | ||

| Blood vessel marker | 12/0 | 0.90 (0.80-1.00) | ||

| HHV-8 | 11/0 | 0.87 (0.75-0.98) | 0.34 |

The ROC-AUC of four specific stains was significantly different in size, GI tract location, appearance of patches, and polypoid lesion for the diagnosis of GI-KS (Table 3). No significant differences were noted in the ROC-AUC of four specific stains for SMT lesions (P = 0.15) or ulcerative SMT lesions (P = 0.34) (Table 3).

The ROC-AUC of the D2-40 stain was higher than that of the HE stain for lesions < 10 mm, lesions ≥ 10 mm, upper GI tract, lower GI tract, patches, polypoids, and SMT (Table 3). Of these, upper GI tract and polypoid appearance were statistically significant (P < 0.05). The ROC-AUC of blood vessel marker or HHV-8 stain was higher than that of HE staining for lesions ≥ 10 mm, patches, and ulcerative SMT (Table 3), with no statistical significance (P > 0.05).

Previous IHC studies have shown the utility of differential diagnosis between cutaneous KS and vascular tumors such as hemangioma, lymphangioma, hemangioendothelioma, and angiosarcoma[19-28]. However, development of vascular tumor in the GI tract is extremely rare[30]. Therefore, differential diagnosis for GI-KS can be different for cutaneous and GI tract sites. In the present study, lesions that were difficult to distinguish from GI-KS are inflammation-associated protruded lesions with reddish color. The reason for this is that GI-KS can appear as a strong reddish mucosa and vary from flat maculopapular or polypoid masses to SMT, ulceration, or bulky tumor masses on endoscopy[14,17,18,29,31].

Previous studies investigated only GI-KS cases, and only sensitivity can be elucidated[14-16]. In the current study, the ROC-AUC values of the four IHC stains and HE stain were > 0.8, demonstrating that all had good diagnostic accuracy. However, it is not feasible in clinical practice to diagnose KS using all stains. Based on the results of this study, we conclude that D2-40 is the only stain capable of complementing HE staining.

We found that the ROC-AUC of four specific stains tended to increase with endoscopic tumor staging (e.g., small to large, flat, protruded, and SMT). Previous studies, particularly those on cutaneous KS, have also shown that diagnostic accuracy varies according to tumor staging[19,21,22,25]. Although it is not feasible to apply staging classification of cutaneous KS to the evaluation of the macroscopic appearance of GI-KS, it is important--based on their results and our findings--to take tumor appearance and staging into consideration for the pathological diagnosis of KS.

We further performed subgroup analysis of four stains to reveal differences in diagnostic accuracy. No significant differences were noted in the ROC-AUC of four specific stains in SMT lesions (P = 0.15) and ulcerative SMT lesions (P = 0.34), indicating that HE staining alone is sufficient for diagnosing lesions with SMT appearance. Although we attempted to find lesions that can be better diagnosed with the addition of other IHC stains, polypoid lesions, and location of upper GI tract attained significant ROC-AUC (P < 0.05) scores with D2-40. The ROC-AUC of D2-40 was always > 0.8, regardless of the size, location, or macroscopic appearance of lesions, indicating its utility as an additional staining modality.

One of the characteristic findings of this study is that the ROC-AUC of the blood vessel marker for polypoid appearance was extremely low compared with other lesions. This was due to the presence of hyperplastic polyps, meaning that CD34 staining produces positive results due to vessel proliferation. This can result in higher false-positive cases (n = 38) and lower diagnostic accuracy of KS.

There are several limitations of the present study. First, we assessed IHC staining as positive or negative instead of using a scoring system; a semi-quantitative system might provide more accurate or available results in clinical practice. Second, positive vessel marker staining was defined as CD31- or CD34-positive because CD31 or CD34 was used by each pathologist. However, because 80% (82/103) of the lesions were examined using CD34, and because CD34 is reportedly a more accurate marker than CD31[25], we believe the results of the vessel marker staining in the present study are reliable.

In conclusion, endoscopic biopsy for diagnosing GI-KS can be performed safely. The diagnostic accuracy of HE staining, lymphatic and blood vessel endothelial cell markers, and HHV-8 was found to be high. Among these, D2-40 had the highest accuracy. The diagnostic accuracy of four specific stains tended to increase with endoscopic tumor staging. In particular, polypoid lesions and those in the upper GI tract respond well to HE staining complemented by D2-40 staining.

We wish to thank Hisae Kawashiro, Clinical Research Coordinator, for assistance with data collection.

Diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma (KS) involving the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is important because treatment specifics depend on the extent of the disease. Definitive diagnosis of GI-KS requires endoscopic biopsy with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) or immunohistochemical (IHC) staining. IHC staining for the differential diagnosis of cutaneous disease has been extensively studied, but the diagnostic value of GI-KS remains unknown.

GI-KS often presents various endoscopic appearances, which can lead to false-negative biopsy results. Furthermore, the difference in accuracy of IHC staining in relation to endoscopic appearances has not been fully investigated. In the current study, the authors demonstrate the diagnostic value of IHC staining for GI-KS and to assess the difference in accuracy between HE and IHC staining in relation to endoscopic tumor staging.

Previous reports have highlighted the accuracy of IHC for diagnosing cutaneous KS. This is the first study to report that the receiver operating characteristic area under the curve (ROC-AUC) of HE staining, lymphatic and blood vessel endothelial cell markers, and HHV-8 for diagnosing GI-KS was found to be high (> 0.80), and its accuracy tended to increase with endoscopic tumor staging. In particular, polypoid lesions and those in the upper GI tract respond well to HE staining complemented by D2-40 staining.

In the current study, the ROC-AUC values of the four IHC stains and HE stain were good, but it is not feasible in clinical practice to diagnose KS using all stains. Based on the results of this study, the authors conclude that D2-40 is the only stain capable of complementing HE staining.

The ROC is a diagnostic testing modality that presents its results as a plot of sensitivity vs 1-specificity (false-positive rate). The ROC-AUC indicates the probability of a measure or predicted risk being higher for patients with disease than for those without disease.

This is an excellent paper describing novel findings of IHC in diagnosing GI-KS.

| 1. | Buchacz K, Baker RK, Palella FJ, Chmiel JS, Lichtenstein KA, Novak RM, Wood KC, Brooks JT. AIDS-defining opportunistic illnesses in US patients, 1994-2007: a cohort study. AIDS. 2010;24:1549-1559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Goedert JJ, Virgo P, McNeel TS, Scoppa SM, Biggar RJ. Trends in cancer risk among people with AIDS in the United States 1980-2002. AIDS. 2006;20:1645-1654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 551] [Cited by in RCA: 541] [Article Influence: 27.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 3. | Biggar RJ, Rabkin CS. The epidemiology of AIDS--related neoplasms. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1996;10:997-1010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mocroft A, Kirk O, Clumeck N, Gargalianos-Kakolyris P, Trocha H, Chentsova N, Antunes F, Stellbrink HJ, Phillips AN, Lundgren JD. The changing pattern of Kaposi sarcoma in patients with HIV, 1994-2003: the EuroSIDA Study. Cancer. 2004;100:2644-2654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Beral V, Peterman TA, Berkelman RL, Jaffe HW. Kaposi’s sarcoma among persons with AIDS: a sexually transmitted infection? Lancet. 1990;335:123-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 800] [Cited by in RCA: 685] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Braun M. Classics in Oncology. Idiopathic multiple pigmented sarcoma of the skin by Kaposi. CA Cancer J Clin. 1982;32:340-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Antman K, Chang Y. Kaposi’s sarcoma. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1027-1038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 672] [Cited by in RCA: 623] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nasti G, Talamini R, Antinori A, Martellotta F, Jacchetti G, Chiodo F, Ballardini G, Stoppini L, Di Perri G, Mena M. AIDS-related Kaposi’s Sarcoma: evaluation of potential new prognostic factors and assessment of the AIDS Clinical Trial Group Staging System in the Haart Era--the Italian Cooperative Group on AIDS and Tumors and the Italian Cohort of Patients Naive From Antiretrovirals. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2876-2882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gallafent JH, Buskin SE, De Turk PB, Aboulafia DM. Profile of patients with Kaposi’s sarcoma in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1253-1260. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Stebbing J, Sanitt A, Nelson M, Powles T, Gazzard B, Bower M. A prognostic index for AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Lancet. 2006;367:1495-1502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Krown SE, Testa MA, Huang J. AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma: prospective validation of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group staging classification. AIDS Clinical Trials Group Oncology Committee. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:3085-3092. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Ioachim HL, Adsay V, Giancotti FR, Dorsett B, Melamed J. Kaposi’s sarcoma of internal organs. A multiparameter study of 86 cases. Cancer. 1995;75:1376-1385. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Danzig JB, Brandt LJ, Reinus JF, Klein RS. Gastrointestinal malignancy in patients with AIDS. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:715-718. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Friedman SL, Wright TL, Altman DF. Gastrointestinal Kaposi’s sarcoma in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Endoscopic and autopsy findings. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:102-108. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Kolios G, Kaloterakis A, Filiotou A, Nakos A, Hadziyannis S. Gastroscopic findings in Mediterranean Kaposi’s sarcoma (non-AIDS). Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:336-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Saltz RK, Kurtz RC, Lightdale CJ, Myskowski P, Cunningham-Rundles S, Urmacher C, Safai B. Kaposi’s sarcoma. Gastrointestinal involvement correlation with skin findings and immunologic function. Dig Dis Sci. 1984;29:817-823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nagata N, Sekine K, Igari T, Hamada Y, Yazaki H, Ohmagari N, Akiyama J, Shimbo T, Teruya K, Oka S. False-Negative Results of Endoscopic Biopsy in the Diagnosis of Gastrointestinal Kaposi’s Sarcoma in HIV-Infected Patients. Patholog Res Int. 2012;2012:854146. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Nagata N, Shimbo T, Yazaki H, Asayama N, Akiyama J, Teruya K, Igari T, Ohmagari N, Oka S, Uemura N. Predictive clinical factors in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal Kaposi’s sarcoma and its endoscopic severity. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cheuk W, Wong KO, Wong CS, Dinkel JE, Ben-Dor D, Chan JK. Immunostaining for human herpesvirus 8 latent nuclear antigen-1 helps distinguish Kaposi sarcoma from its mimickers. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:335-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dubina M, Goldenberg G. Positive staining of tumor-stage Kaposi sarcoma with lymphatic marker D2-40. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:276-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hong A, Davies S, Lee CS. Immunohistochemical detection of the human herpes virus 8 (HHV8) latent nuclear antigen-1 in Kaposi’s sarcoma. Pathology. 2003;35:448-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kandemir NO, Barut F, Gun BD, Keser SH, Karadayi N, Gun M, Ozdamar SO. Lymphatic differentiation in classic Kaposi’s sarcoma: patterns of D2-40 immunoexpression in the course of tumor progression. Pathol Oncol Res. 2011;17:843-851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Patel RM, Goldblum JR, Hsi ED. Immunohistochemical detection of human herpes virus-8 latent nuclear antigen-1 is useful in the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:456-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Robin YM, Guillou L, Michels JJ, Coindre JM. Human herpesvirus 8 immunostaining: a sensitive and specific method for diagnosing Kaposi sarcoma in paraffin-embedded sections. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:330-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Russell Jones R, Orchard G, Zelger B, Wilson Jones E. Immunostaining for CD31 and CD34 in Kaposi sarcoma. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:1011-1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wada DA, Perkins SL, Tripp S, Coffin CM, Florell SR. Human herpesvirus 8 and iron staining are useful in differentiating Kaposi sarcoma from interstitial granuloma annulare. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;127:263-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rosado FG, Itani DM, Coffin CM, Cates JM. Utility of immunohistochemical staining with FLI1, D2-40, CD31, and CD34 in the diagnosis of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related and non-acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:301-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kahn HJ, Bailey D, Marks A. Monoclonal antibody D2-40, a new marker of lymphatic endothelium, reacts with Kaposi’s sarcoma and a subset of angiosarcomas. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:434-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 459] [Cited by in RCA: 431] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Nagata N, Yazaki H, Oka S. Kaposi’s sarcoma presenting as a bulky tumor mass of the colon. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:A22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Mignogna C, Simonetti S, Galloro G, Magno L, De Cecio R, Insabato L. Duodenal epithelioid angiosarcoma: immunohistochemical and clinical findings. A case report. Tumori. 2007;93:619-621. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Kahl P, Buettner R, Friedrichs N, Merkelbach-Bruse S, Wenzel J, Carl Heukamp L. Kaposi’s sarcoma of the gastrointestinal tract: report of two cases and review of the literature. Pathol Res Pract. 2007;203:227-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewers Hokama A, Tang QY S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN