Published online May 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i19.2956

Revised: March 24, 2013

Accepted: April 10, 2013

Published online: May 21, 2013

Processing time: 116 Days and 17.4 Hours

AIM: To study the effect and tolerance of intraperitoneal perfusion of cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells in combination with local radio frequency (RF) hyperthermia in patients with advanced primary hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

METHODS: Patients with advanced primary HCC were included in this study. CIK cells were perfused intraperitoneal twice a week, using 3.2 × 109 to 3.6 × 109 cells each session. Local RF hyperthermia was performed 2 h after intraperitoneal perfusion. Following an interval of one month, the next course of treatment was administered. Patients received treatment until disease progression. Tumor size, immune indices (CD3+, CD4+, CD3+CD8+, CD3+CD56+), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level, abdominal circumference and adverse events were recorded. Time to progression and overall survival (OS) were calculated.

RESULTS: From June 2010 to July 2011, 31 patients diagnosed with advanced primary HCC received intraperitoneal perfusion of CIK cells in combination with local RF hyperthermia in our study. Patients received an average of 4.2 ± 0.6 treatment courses (range, 1-8 courses). Patients were followed up for 8.3 ± 0.7 mo (range, 2-12 mo). Following combination treatment, CD4+, CD3+CD8+ and CD3+CD56+ cells increased from 35.78% ± 3.51%, 24.61% ± 4.19% and 5.94% ± 0.87% to 45.83% ± 2.48% (P = 0.016), 39.67% ± 3.38% (P = 0.008) and 10.72% ± 0.67% (P = 0.001), respectively. AFP decreased from 167.67 ± 22.44 to 99.89 ± 22.05 ng/mL (P = 0.001) and abdominal circumference decreased from 97.50 ± 3.45 cm to 87.17 ± 4.40 cm (P = 0.002). The disease control rate was 67.7%. The most common adverse events were low fever and slight abdominal erubescence, which resolved without treatment. The median time to progression was 6.1 mo. The 3-, 6- and 9-mo and 1-year survival rates were 93.5%, 77.4%, 41.9% and 17.4%, respectively. The median OS was 8.5 mo.

CONCLUSION: Intraperitoneal perfusion of CIK cells in combination with local RF hyperthermia is safe, can efficiently improve immunological status, and may prolong survival in HCC patients.

Core tip: Intraperitoneal perfusion of cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells in combination with local radio frequencyc hyperthermia can result in a high concentration of CIK cells. This treatment can efficiently improve immunological status, and attack small lesions in the abdominal wall, which can reduce ascites and relieve abdominal distention. This comprehensive treatment may prolong survival time and improve quality of life in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma.

- Citation: Wang XP, Xu M, Gao HF, Zhao JF, Xu KC. Intraperitoneal perfusion of cytokine-induced killer cells with local hyperthermia for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(19): 2956-2962

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i19/2956.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i19.2956

Primary hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common malignant tumors worldwide and has a poor prognosis. Surgical resection at an early stage is still the best remedy[1]. As the onset of HCC is occult, it is typically diagnosed in stage III-IV when patients present with clinical symptoms. However, the surgical resection rate is only 10%-30%. Currently, there is still no standard treatment for advanced HCC, but minimally invasive therapy and targeted therapy are favored. Patients with HCC may have poor therapeutic outcomes due to multiple local lesions or excessive tumor load. Consequently, integrative therapy is now a useful treatment for patients with advanced HCC[2].

Adoptive cellular immunotherapy has been applied in the clinical treatment of advanced HCC due to the close relationship between the pathogenesis of HCC and the autoimmune system, and the persistence of pathogenic factors such as hepatitis and cirrhosis[3-5]. Cellular immunotherapy includes several types of immunological cells, such as lymphokine-activated killer cells, tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells. CIK cells have been confirmed to have potential for immunotherapy against residual tumor cells. In recent years, several authors have reported that CIK cells were a heterogeneous population, and the major population to express both T cell marker monoclonal antibody and natural killer cell marker monoclonal antibody[6]. Cells with this phenotype are rare (1%-5%) in natural peripheral blood mononuclear cells. CIK cells are able to expand nearly 1000-fold when cultured in a cytokine cocktail, comprising interleukin (IL)-1α, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), IL-2 and mAbs against CD3, and have characteristics which are more effective in the treatment of tumors with a non-major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-restricted mechanism[7]. Thus, CIK cells may have some benefit in potential immunotherapeutic treatments in patients with HCC.

Hyperthermia treatment of tumors refers to tumor tissue which is treated with a continuous direct current through two or more electrodes placed outside the tumor. Some researchers have suggested that hyperthermia can normalize cell growth, and accelerate cell division after inhibiting cell division when it becomes abnormally accelerated[8,9]. Hyperthermia is an alternative treatment for HCC patients and has a positive effect on tumors. This study aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the combination of CIK cell therapy and local radio frequency (RF) hyperthermia in patients with advanced HCC.

From June 2010 to July 2011, 31 patients with advanced HCC in the Oncology Center of Clifford Hospital were included in this study. Seven patients were identified by pathological diagnosis and the remaining patients all met the clinical diagnostic criteria[10]. Staging of disease was by tumor-node- metastasis staging according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging criteria[11]. All patients were stage III-IV without metastases outside the abdomen. Reasons for being unable to undergo surgery and transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) were as follows: multiple tumors with obscure boundaries, extremely small remnant liver, lesions close to or involving great vessels, extreme damage to the cardiovascular system or other organs, liver functional lesion and rejection of surgery or TACE. Written informed consent was obtained before treatment.

The instrument used was the FACS Calibur Flow cytometer (manufactured by BD Biosciences, United States). The reagents required for incubation of CIK cells were as follows: IL-1α (10 μg/vial, PeproTech Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ, United States), monoclonal mouse anti-human CD3 (500 μg/vial, PeproTech Inc.), IFN-γ (1000000 U/vial, PeproTech Inc.), IL-2 (PeproTech Inc.), complete Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium (GIBCO, RPMI 1640 + gentamicin + 5% human type AB serum), lymphocyte separation medium (Tianjin Biological Products Company, Tianjin, China), human type AB serum (Tianjin Biological Products Company) and normal saline.

CIK cells were prepared by the Cell Laboratory as follows: mononuclear cells were isolated from 50 mL peripheral blood from each patient using a blood cell separator, and then incubated in medium containing 1000 U/mL IFN-γ at 37 °C; 24 h later 100 ng/mL monoclonal mouse anti-human CD3, 1000 U/mL IL-2 and 1000 U/mL IL-lα were added; the culture medium was renewed every 3 d and rhIL-2 was replenished. After 7-10 d, CIK cells were collected when the cell count reached 3.2 × 109 to 3.6 × 109, centrifuged, washed with normal saline, dispersed in 100 mL normal saline (containing 5 mL 20% human serum albumin) and retained as a sample.

Routine abdominocentesis was performed before intraperitoneal perfusion of CIK cells and a tube was left in the abdomen for perfusion. After abdominocentesis, 100-200 mL physiologic saline was perfused into the abdomen and observations on defecation sensation, discomfort, and whether the tube was smooth and in the correct position for the preparation of intraperitoneal perfusion of CIK cells were carried out. Patients with a recent history of surgery or suspicious ankylenteron required ultrasonic guidance during abdominocentesis.

The machine used was an EHY-2000 local RF Hyperthermia Machine, made in Hungary. Health education and psychological preparation were carried out prior to treatment. Patients were evaluated for dysmetabolism and disturbed perception of temperature. Patients were asked to lie on the treatment water bed in the correct body position according to treatment requirements. An appropriate electrode plate size was chosen to cover the body surface projection area of the tumor. Treatment time was 60 min per session and power was 100-150 W (according to the tolerance level of patients).

Intraperitoneal perfusion of CIK cells was performed twice a week (Monday and Thursday), with 3.2 × 109 to 3.6 × 109 cells each session. Local RF hyperthermia was carried out 2 h after intraperitoneal perfusion. In one treatment course consisting of 4 sessions, 1.2 × 1010 to 1.5 × 1010 cells were perfused. After an interval of one month, the next treatment course was administered, resulting in a time period of 1.5 mo for one cycle. Patients received treatment until disease progression or intolerant adverse effects.

Patients were followed up for 1 year. The treatment process, adverse reactions, and lost cases were recorded. A computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging scan of the liver was performed every 2 mos. The size and number of tumors before and after treatment were compared. The therapeutic effect was evaluated and recorded. Levels of peripheral blood T lymphocyte subgroups (CD3+, CD4+, CD3+CD8+ and CD3+CD56+), abdominal circumference (patients with seroperitoneum) and AFP level were determined every 2 wk. Time to progression (TTP) and overall survival (OS) were calculated.

Results were analyzed using SPSS 17.0 software. The data were expressed as mean ± SD. The survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

From June 2010 to July 2011, a total of 31 patients aged 28-61 years (mean 47.6 ± 8.8 years) were included in this study. The characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

| Characteristics | n (%) |

| Patient | |

| Gender (M/F) | 22/9 |

| Age, yr (range) | 47.6 ± 8.8 (28-61) |

| Stage status | |

| III | 18 (58.06) |

| IV | 13 (41.93) |

| Complications | |

| Seroperitoneum | 14 (45.16) |

| Hypoproteinemia | 17 (54.83) |

| Choloplania | 8 (25.80) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 3 (9.67) |

| 1 | 18 (58.06) |

| 2 | 10 (32.25) |

| Past history before treatment | |

| Surgery | 4 (12.90) |

| TACE | 7 (22.58) |

| Chemotherapy | 1 (3.22) |

| Surgery + TACE | 8 (25.80) |

| Surgery + chemotherapy | 2 (6.45) |

| TACE + chemotherapy | 3 (9.67) |

| Initial treatment | 6 (19.35) |

According to the Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors, none (0%) of the patients had a complete response, 10 (32.25%) patients had a partial response (PR), 11 (35.48%) patients had no change (SD), and 10 (32.25%) patients had progressive disease. After treatment, AFP level decreased from 167.67 ± 22.44 to 99.89 ± 22.05 ng/mL (P = 0.001) and seroperitoneum in 14 patients significantly decreased, with abdominal circumference decreasing from 97.50 ± 3.45 to 87.17 ± 4.40 cm (P = 0.002).

The immunologic markers examined included the serum levels of CD3+, CD4+, CD3+CD8+ and CD3+CD56+ T cells. After CIK cells were transfused back into the patients, all of these immune parameters increased, but not all of them increased significantly (Table 2).

| Group | Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | P value |

| CD3+ | 70.44% ± 6.68% | 72.67% ± 6.22% | 0.55 |

| CD4+ | 35.78% ± 3.51% | 45.83% ± 2.48% | 0.016 |

| CD3+CD8+ | 24.61% ± 4.19% | 39.67% ± 3.38% | 0.008 |

| CD3+CD56+ | 5.94% ± 0.87% | 10.72% ± 0.67% | 0.001 |

No serious adverse events were observed in this study. Several mild adverse events were observed, which rapidly resolved without treatment (Table 3).

| Side effects | n (%) |

| Abdominal side effects | |

| Abdominal pain | 3 (9.67) |

| Abdominal erubescence | 5 (16.12) |

| Abdominal lesser tubercle | 1 (3.22) |

| Systemic side effects | |

| Slight fever | 4 (12.90) |

| Dizziness | 3 (9.67) |

| Debilitation | 6 (19.35) |

| Nausea or vomiting | 1 (3.22) |

| Diarrhea | 2 (6.44) |

| Tachycardia | 1 (3.22) |

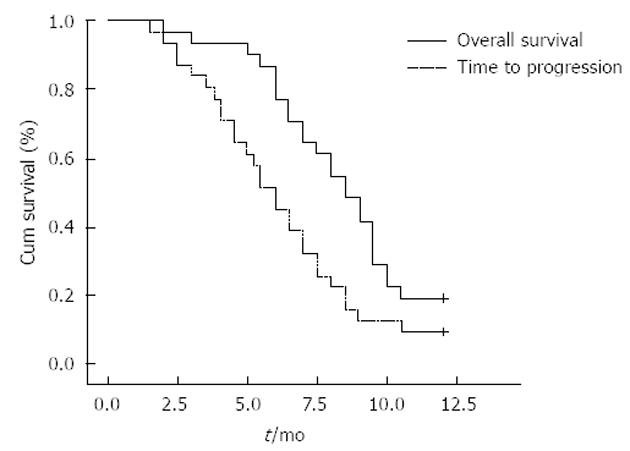

TTP and OS were assessed in all 31 eligible patients. The median follow-up was 8.3 ± 0.7 mo (range, 2-12 mo). At the time of the analysis, 25 patients were dead and 6 patients were alive. The median TTP was 6.1 mo (95%CI: 4.8-7.2). The 3-, 6- and 9-mo and 1-year survival rates were 93.5%, 77.4%, 41.9% and 17.4%, respectively. The median OS was 8.5 mo (Figure 1).

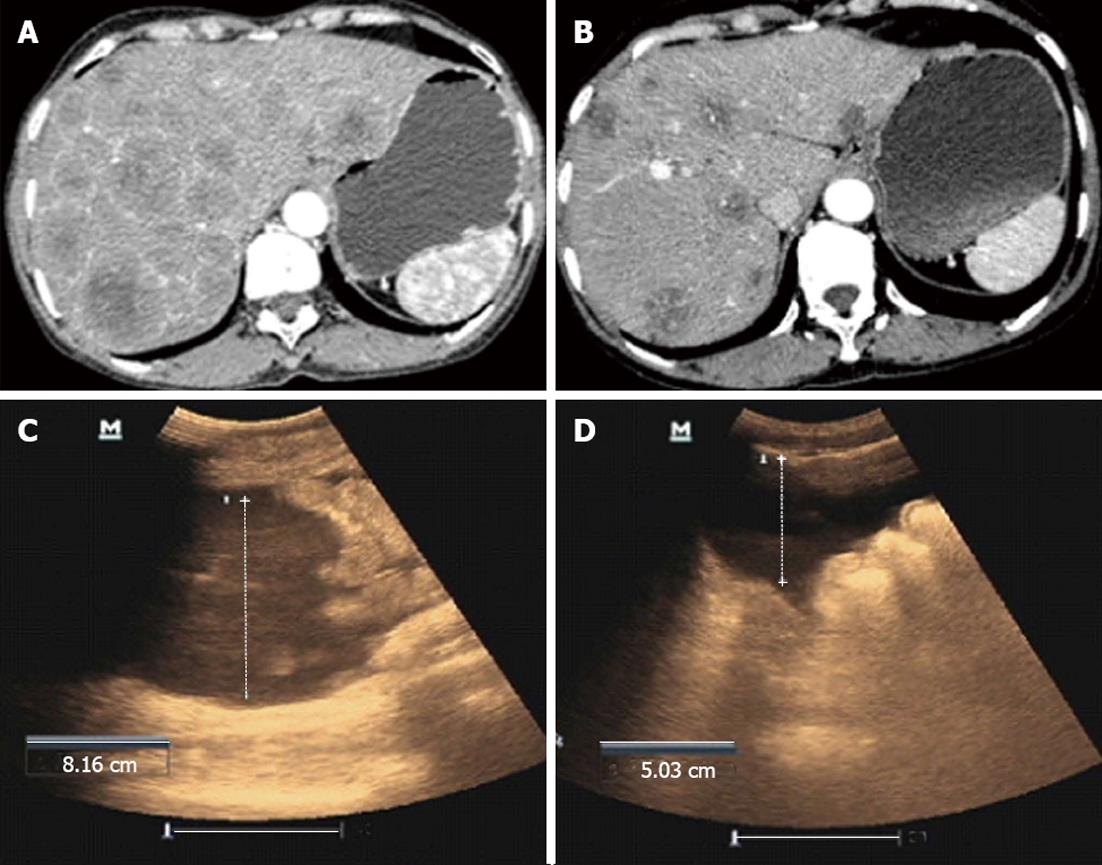

A 57-year-old male was diagnosed with primary HCC by CT-guided aspiration biopsy of the liver in July 2010. Diffuse lesions in the liver with portal vein encroachment were observed on the CT scan. The patient also had complications of abdominal distention, debilitation, lack of appetite and emaciation. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) was 2. AFP level was 201 ng/mL, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 70 U/L, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 120 U/L. T lymphocyte subgroups were CD3+ 76%, CD4+ 22%, CD3+CD8+ 17%, and CD3+CD56+ 5.6%, respectively. The patient received 3 cycles of intraperitoneal CIK cells in combination with local RF hyperthermia. The patient achieved a PR. AFP fell to 98 ng/mL and ECOG increased to 1. ALT and AST fell to normal levels. T lymphocyte subgroups were CD3+ 77%, CD4+ 34%, CD3+CD8+ 27% and CD3+CD56+ 9.1%, respectively (Figure 2A and B).

A 51-year-old male was admitted to hospital due to abdominal distention and pain. The patient was diagnosed with primary hepatic carcinoma in December 2012, and underwent surgery in a local hospital with postoperative Sorafenib therapy. The patient had been experiencing obvious abdominal distention with abdominal pain, poor appetite, nausea, and emesis for 1 mo. Enhanced CT scanning showed multiple metastases in the liver, metastases in the portal lymph nodes and significant seroperitoneum. Due to the advanced stage of hepatic carcinoma, further surgical treatment and interventional therapies were inappropriate. Considering the failure of targeted drug treatment, intraperitoneal perfusion of CIK cells in combination with local RF hyperthermia was administered to the patient. Before treatment, abdominal circumference was 97.5 cm. Ultrasound examination showed that the deepest portion of seroperitoneum was 8.16 cm. After 1 cycle of treatment with intraperitoneal perfusion of CIK cells in combination with local RF hyperthermia, the patient noted that abdominal distension was significantly reduced, with a decrease in abdominal circumference to 93.0 cm and seroperitoneum decreased to 5.03 cm under ultrasound examination (Figure 2C and D).

Recently, targeted therapy and palliative chemotherapy have been the main treatment approaches for patients with advanced HCC. New targeted drugs such as sorafenib and sunitinib have improved clinical efficacy. However, the serious side effects and high costs of these drugs make it impossible for many patients to complete the entire treatment course[12,13]. Thus, it is necessary to investigate alternative therapies for patients with advanced HCC.

The special biological behavior of primary HCC, such as multiple lesions, existing hepatitis and cirrhosis, continuously suppresses cellular immunity and results in immune dysfunction. Autoimmune disorders in patients with HCC is manifested by lower levels of CD4+ and CD3+CD56+ cells and significantly higher levels of CD8+ cells[14,15]. The ability to efficiently kill tumor cells is the ultimate requirement in immune effector candidates for adoptive immunotherapy. CIK cells have a MHC-independent tumor killing capacity in both solid and hematologic malignancies. The antitumor activity is mainly associated with a high percentage of the CD3+CD56+ subset[16,17]. The exact mechanism involved in tumor recognition and killing is not completely known, but mainly involves the secretion of a cytokine to inhibit the growth of tumor cells[18-20].

It has been demonstrated that CIK cells are effective against some solid malignancies including lung, gastrointestinal and mesenchymal tumors both in vitro and in vivo[21,22]. Olioso et al[23] reported 12 patients (6 advanced lymphomas, 5 metastatic kidney carcinomas and 1 HCC) who were intravenously transfused with 28 × 109 (range, 6 × 109 to 61 × 109) CIK cells per patient during one cycle. The treatment schedule consisted of three cycles of CIK cell infusions at an interval of 3 wk. After treatment, the absolute median number of lymphocytes, CD3+, CD8+ and CD3+CD56+ cells significantly increased in peripheral blood. In our study, CD4+, CD3+CD8+ and CD3+CD56+ cells increased after treatment from 35.78% ± 3.51%, 24.61% ± 4.19% and 5.94% ± 0.87% to 45.83% ± 2.48% (P = 0.016), 39.67% ± 3.38% (P = 0.008) and 10.72% ± 0.67% (P = 0.001), respectively. Our results were similar to those of Olioso et al[23].

The most common causes of death in patients with advanced HCC are liver failure, ascites and obstruction. Control of the abdominal tumor is the principal goal of treatment, which can prolong survival and improve quality of life. Recently, intravenous infusion of CIK cells has been widely used in the treatment of HCC. However, the concentration of CIK cells is low in tumor tissues following intravenous infusion, and the anti-tumor effect is low. In this study, in order to achieve a high concentration of CIK cells in the abdomen, CIK cells were perfused intraperitoneally instead of intravenously. Intraperitoneal perfusion of CIK cells in combination with local RF hyperthermia can improve efficacy in clinical practice. The primary reason for this may be that hyperthermia accelerates the conjugation of CIK cells and tumor cells, which improves the reaction rate of CIK cells. Local RF hyperthermia after high-capacity perfusion of CIK cells improves the sensitivity of tumor cells, allowing CIK cells to permeate into tumor cells more effectively.

Local RF hyperthermia kills tumor cells by heating using physical energy and the temperature of tumor tissue rises to an effective treatment temperature. Studies have shown that high temperature can damage the membranes of mitochondria, lysosomes and endoplasmic reticulum and triggers the massive release of acid hydrolase from lysosomes, resulting in membranolysis, outflow of cytoplasm and death of cancer cells[24,25]. In addition, some studies have reported that hyperthermia improves immune function by stimulating the development of the anti-tumor immune effect and resolving the inhibition of blocking factors in the immune system[26]. The core points behind this treatment were to administer intraperitoneal perfusion of CIK cells to improve immune function to kill the tumor, and local hyperthermia to enhance the concentration of CIK cells which directly affect liver tumor tissues and small lesions on the abdominal wall, which can damage cancer cells and effectively reduce abdominal dropsy. Local hyperthermia plays an important role in enhancing the concentration of CIK cells which directly affect these parameters.

The most common adverse events in our study were low fever and slight abdominal erubescence, which resolved without treatment. No serious side effects were observed. During the treatment process, 4 patients experienced low fever ranging from 37.5-38 °C, which resolved without treatment. This fever might have been caused by the application of IL-2. Some other symptoms, including erubescence and lesser tubercle of abdominal subcutaneous fat, were observed, which were caused by high temperature and were relieved by simple symptomatic treatment. Intraperitoneal perfusion of autologous CIK cells can avoid immune rejection triggered by foreign cell infusion.

In conclusion, intraperitoneal perfusion of CIK cells in combination with local RF hyperthermia is safe and effective for advanced HCC. More clinical trials with a large sample size are warranted to provide evidence for further applications. The addition of palliative chemotherapy or targeted therapy is worthy of further investigation.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common malignant tumors worldwide. Recently, integrative therapy has become a useful treatment for patients with advanced HCC. Due to the close relationship between the pathogenesis of HCC and the autoimmune system, cellular immunotherapy has been used in the clinical treatment of advanced HCC. In addition, local hyperthermia increases the role of cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells in killing tumor tissues.

Intraperitoneal perfusion of CIK cells in combination with local radio frequency (RF) hyperthermia can improve immune function in HCC patients, shrink the tumor, and relieve discomfort such as debilitation and abdominal distention.

Recently, intravenous infusion of CIK cells has been widely used in the treatment of HCC. However, the concentration of CIK cells is low in tumor tissues following intravenous infusion, and the anti-tumor effect is low. In their research, intraperitoneal perfusion of CIK cells in combination with local RF hyperthermia resulted in a high concentration of CIK cells in the abdominal cavity and effective killing of tumor tissues.

The authors have been using this treatment strategy for more than 1 year. Forty-two patients accepted this treatment, of whom 31 were selected for this study. There were no serious adverse events following this treatment. A few patients showed low-grade fever or slight chest distress which resolved after symptomatic treatment. Following intraperitoneal perfusion of CIK cells in combination with local RF hyperthermia, abdominal distention resolved, tumor size diminished, and survival time was prolonged in some patients. This treatment strategy is worthy of further investigation.

CIK cells are alloplasmic cells with non-major histocompatibility complex (MHC) restriction anti-tumor activity which is acquired by multiple-cell factor-cultivation in vitro from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. CD3+CD56+ T is the main effector cell of the CIK cell group, and is also called nature killer cell-like T lympholeukocyte. These cells have powerful anti-tumor activity and MHC restriction of T lympholeukocytes. Local RF hyperthermia is used in the non-invasive treatment of malignant tissues. The difference between the complex dielectric constant (complex impedance) of malignant and healthy tissues makes it possible to select malignant tissues.

In this study, 31 patients with advanced HCC who could not be treated by surgical treatments or interventional therapies, were treated by CIK cell intraperitoneal perfusion in combination with RF local hyperthermia. The result showed that this treatment is safe and reliable, and worthy of further clinical studies of a larger sample. It is a new option of treatment for patients with advanced HCC.

| 1. | Rimassa L, Santoro A. The present and the future landscape of treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42 Suppl 3:S273-S280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhu AX. Systemic treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: dawn of a new era? Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1247-1256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Thakur S, Singla A, Chawla Y, Rajwanshi A, Kalra N, Arora SK. Expansion of peripheral and intratumoral regulatory T-cells in hepatocellular carcinoma: a case-control study. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:448-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gomez-Santos L, Luka Z, Wagner C, Fernandez-Alvarez S, Lu SC, Mato JM, Martinez-Chantar ML, Beraza N. Inhibition of natural killer cells protects the liver against acute injury in the absence of glycine N-methyltransferase. Hepatology. 2012;56:747-759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Flecken T, Schmidt N, Spangenberg HC, Thimme R. [Hepatocellular carcinoma - from immunobiology to immunotherapy]. Z Gastroenterol. 2012;50:47-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mesiano G, Todorovic M, Gammaitoni L, Leuci V, Giraudo Diego L, Carnevale-Schianca F, Fagioli F, Piacibello W, Aglietta M, Sangiolo D. Cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells as feasible and effective adoptive immunotherapy for the treatment of solid tumors. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2012;12:673-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kim HM, Kang JS, Lim J, Kim JY, Kim YJ, Lee SJ, Song S, Hong JT, Kim Y, Han SB. Antitumor activity of cytokine-induced killer cells in nude mouse xenograft model. Arch Pharm Res. 2009;32:781-787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yuan GJ, Li QW, Shan SL, Wang WM, Jiang S, Xu XM. Hyperthermia inhibits hypoxia-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4781-4786. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Mohamed F, Stuart OA, Glehen O, Urano M, Sugarbaker PH. Docetaxel and hyperthermia: factors that modify thermal enhancement. J Surg Oncol. 2004;88:14-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chinese Medical Association. The diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma, Chinese Medical Association medical guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and treatment of oncology. Beijing: People’s Medicine Publishing House 2005; 303-326. |

| 11. | Greene FL, Sobin LH. A worldwide approach to the TNM staging system: collaborative efforts of the AJCC and UICC. J Surg Oncol. 2009;99:269-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Finn RS. Emerging targeted strategies in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2013;33 Suppl 1:S11-S19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bassi N, Caratozzolo E, Bonariol L, Ruffolo C, Bridda A, Padoan L, Antoniutti M, Massani M. Management of ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma: implications for therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1221-1225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lee WC, Wu TJ, Chou HS, Yu MC, Hsu PY, Hsu HY, Wang CC. The impact of CD4+ CD25+ T cells in the tumor microenvironment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Surgery. 2012;151:213-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chen KJ, Zhou L, Xie HY, Ahmed TE, Feng XW, Zheng SS. Intratumoral regulatory T cells alone or in combination with cytotoxic T cells predict prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma after resection. Med Oncol. 2012;29:1817-1826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ma Y, Xu YC, Tang L, Zhang Z, Wang J, Wang HX. Cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cell therapy for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: efficacy and safety. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2012;1:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nakano M, Saeki C, Takahashi H, Homma S, Tajiri H, Zeniya M. Activated natural killer T cells producing interferon-gamma elicit promoting activity to murine dendritic cell-based autoimmune hepatic inflammation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;170:274-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wang Y, Dai H, Li H, Lv H, Wang T, Fu X, Han W. Growth of human colorectal cancer SW1116 cells is inhibited by cytokine-induced killer cells. Clin Dev Immunol. 2011;2011:621414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pievani A, Borleri G, Pende D, Moretta L, Rambaldi A, Golay J, Introna M. Dual-functional capability of CD3+CD56+ CIK cells, a T-cell subset that acquires NK function and retains TCR-mediated specific cytotoxicity. Blood. 2011;118:3301-3310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yang Z, Zhang Q, Xu K, Shan J, Shen J, Liu L, Xu Y, Xia F, Bie P, Zhang X. Combined therapy with cytokine-induced killer cells and oncolytic adenovirus expressing IL-12 induce enhanced antitumor activity in liver tumor model. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sangiolo D, Martinuzzi E, Todorovic M, Vitaggio K, Vallario A, Jordaney N, Carnevale-Schianca F, Capaldi A, Geuna M, Casorzo L. Alloreactivity and anti-tumor activity segregate within two distinct subsets of cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells: implications for their infusion across major HLA barriers. Int Immunol. 2008;20:841-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kuçi S, Rettinger E, Voss B, Weber G, Stais M, Kreyenberg H, Willasch A, Kuçi Z, Koscielniak E, Klöss S. Efficient lysis of rhabdomyosarcoma cells by cytokine-induced killer cells: implications for adoptive immunotherapy after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Haematologica. 2010;95:1579-1586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Olioso P, Giancola R, Di Riti M, Contento A, Accorsi P, Iacone A. Immunotherapy with cytokine induced killer cells in solid and hematopoietic tumours: a pilot clinical trial. Hematol Oncol. 2009;27:130-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ito A, Okamoto N, Yamaguchi M, Kawabe Y, Kamihira M. Heat-inducible transgene expression with transcriptional amplification mediated by a transactivator. Int J Hyperthermia. 2012;28:788-798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhao C, Dai C, Chen X. Whole-body hyperthermia combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the treatment of stage IV advanced gastric cancer. Int J Hyperthermia. 2012;28:735-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ahlers O, Hildebrandt B, Dieing A, Deja M, Böhnke T, Wust P, Riess H, Gerlach H, Kerner T. Stress induced changes in lymphocyte subpopulations and associated cytokines during whole body hyperthermia of 41.8-42.2 degrees C. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2005;95:298-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewers Han SB, Introna M, Zhong H S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L