Published online Apr 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i13.2118

Revised: January 23, 2013

Accepted: February 7, 2013

Published online: April 7, 2013

Processing time: 127 Days and 18.1 Hours

Intramural duodenal hematoma (IDH) is a rare complication following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Blunt damage caused by the endoscope or an accessory has been suggested as the main reason for IDH. Surgical treatment of isolated duodenal hematoma after blunt trauma is traditionally reserved for rare cases of perforation or persistent symptoms despite conservative management. Typical clinical symptoms of IDH include abdominal pain and vomiting. Diagnosis of IDH can be confirmed by imaging techniques, such as magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Duodenal hematoma is mainly treated by drainage, which includes open surgery drainage and percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage, both causing great trauma. Here we present a case of massive IDH following ERCP, which was successfully managed by minimally invasive management: intranasal hematoma aspiration combined with needle knife opening under a duodenoscope.

- Citation: Pan YM, Wang TT, Wu J, Hu B. Endoscopic drainage for duodenal hematoma following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(13): 2118-2121

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i13/2118.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i13.2118

Intramural duodenal hematoma (IDH) following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is very rare. It is usually caused by blunt damage induced by the endoscope or accessory equipment. The typical clinical symptoms of duodenal hematoma include abdominal pain and vomiting, which are directly induced by duodenal obstruction. The hematoma may also lead to obstruction of the papilla opening, and pancreatitis and cholestasis may follow. The clinical presentations and imaging techniques, e.g., ultrasound, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT), can confirm the diagnosis. A search of PubMed revealed that there has been no previous report on transnasal endoscopic drainage for treatment of duodenal hematoma. Duodenal hematoma is mainly treated by open surgery drainage and percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage (PTCD)[1,2]. However, both cause great trauma. In this paper we report our successful experience on minimally invasive management of a massive IDH following ERCP using intranasal hematoma aspiration combined with needle knife opening under duodenoscopy, which can be done under direct vision, with less trauma and risk.

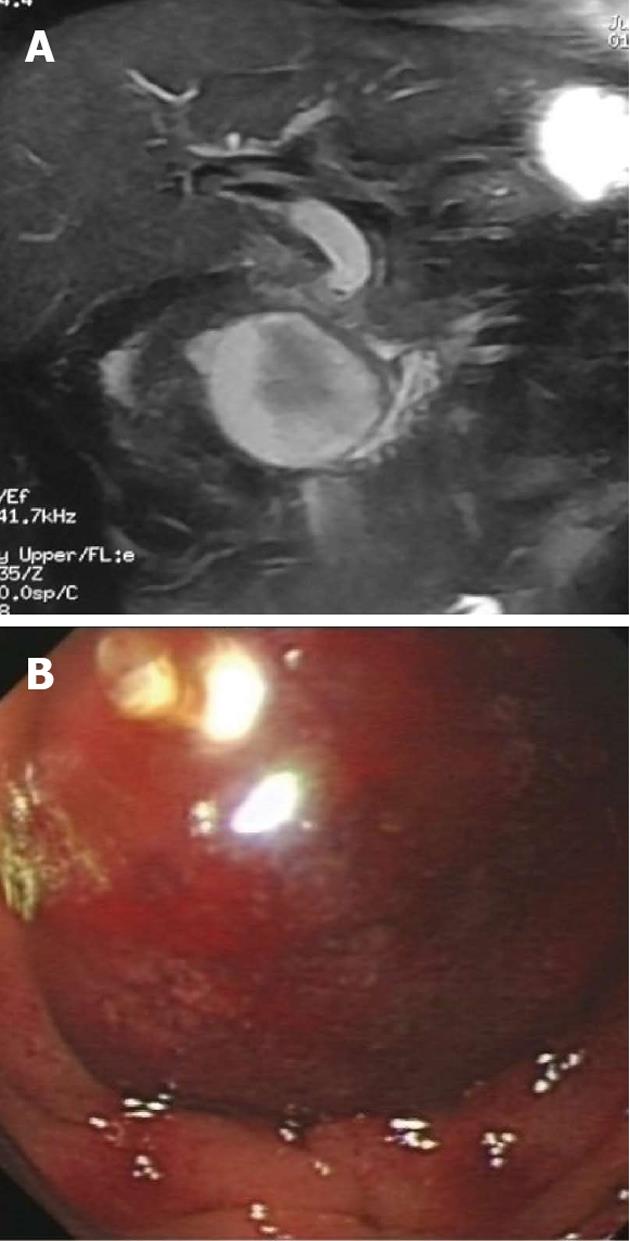

A 48-year-old male patient presented with epigastric distention and abdominal pain after removing a stone in the common bile duct by ERCP. Before ERCP, the patient had abdominal discomfort, and examination found a common bile duct stone, with no history of hypertension or coagulation disorders. Laboratory findings before ERCP were as follows: total/direct bilirubin (Tbil/Dbil): 10.2/4.0 mmol/L; white blood cells (WBC) 4.0 × 109/L, 59.4%; γ-glutamyltransferase (γ-GT): 196 U/L; coagulation function: fibrinogen (Fbg): 1.6 g/L; prothrombin time (PT): 12.6 s. The patient began to vomit after 1 wk. A CT scan showed a 59 mm × 53 mm intact cyst near the head of pancreas in the duodenum (Figure 1A), suspicious of duodenal hematoma. Hepatic function was as follows: γ-GT: 337 U/L; Tbil/Dbil: 19.2/8.0 mmol/L; WBC: 5.6 × 109/L, 73.4%; Fbg: 2.7 g/L; PT: 13.9 s; and blood amylase was normal.

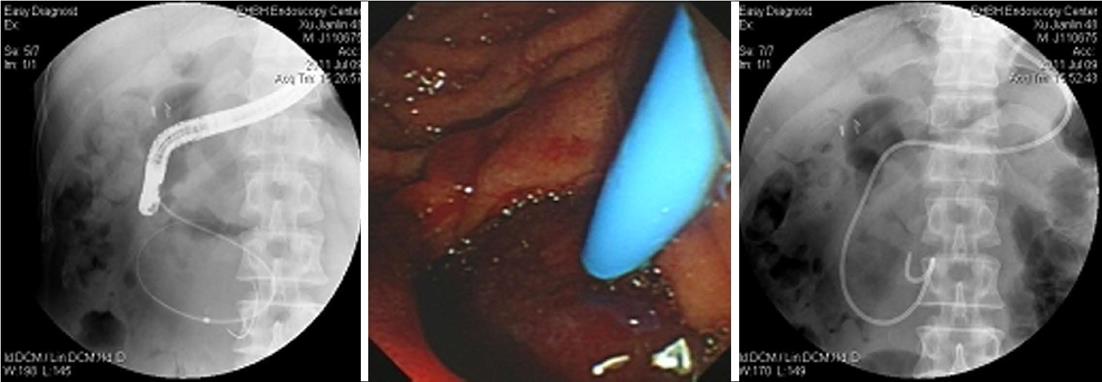

Liver function examination showed a γ-GT of 196 U/L. Emergency duodenoscope inspection revealed a huge cystic bulging object in the intestinal wall of the duodenum, obstructing the duodenum (Figure 1B). A duodenoscope could not pass the obstruction, and the opening of the duodenal papilla was covered by the hematoma. The diagnosis was confirmed as a duodenum hematoma after ERCP. We punctured the hematoma with a needle knife, then inserted a guidewire and catheter (Figure 2) and extracted 100 mL dark red bloody fluid. The fluid became light red after washing with 1:10 000 epinephrine:saline and metronidazole. When the tension of hematoma became smaller, it was found that the hematoma was located at the lateral descending duodenum, 3 cm from the opening of the main papilla. There was no blood at the opening of papilla, and normal bile flowed out from the opening. X-ray showed the bile duct was full of gas. Then we placed a 8.5F per nasal drainage pipe into the hematoma for continuous drainage (Figure 2).

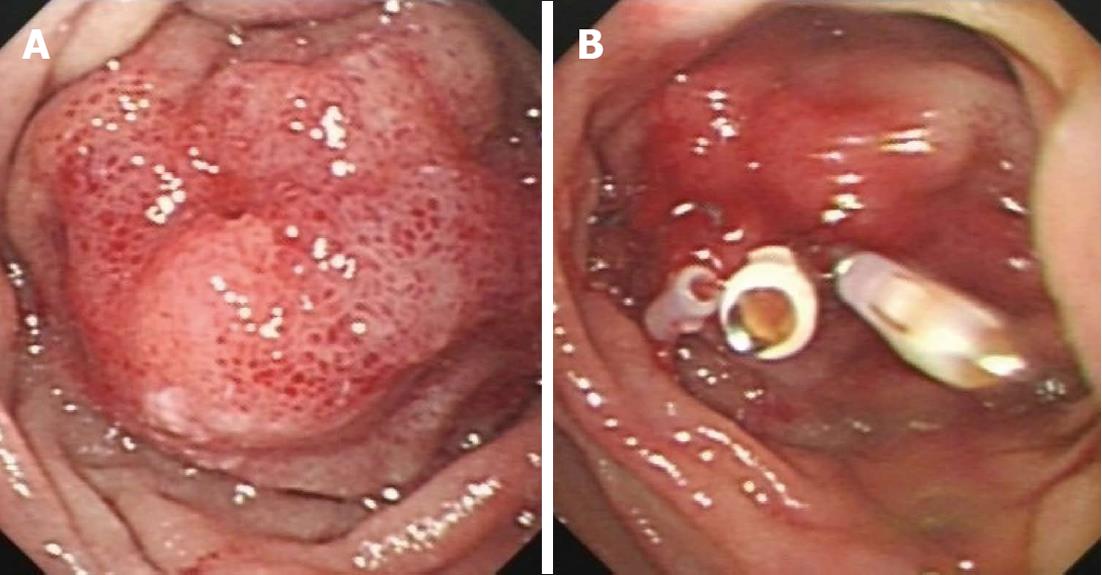

The epigastric distention and abdominal pain were greatly relieved after hematoma drainage, and the patient could ingest semi-fluid without vomiting. Dark red hydatid fluid (about 20 mL) was continuously extracted from the hematoma each day for 2-3 d, and the drainage volume was 5 mL at 5 d after the operation; the patient developed a low fever (38.2 °C) on the 2nd day after the operation. Duodenoscopy examination was performed again after drainage for 5 d, and it was found that the hematoma was smaller, but the local mucosa still had hyperemia and edema (Figure 3A); the duodenoscope could be easily passed without bleeding and edema at opening of the papilla. The drainage tube was removed and the puncture site was closed with hemostatic clips (Figure 3B). Then we explored the extra-hepatic bile ducts again with a stone basket and found no stones. We placed an endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) tube in the common bile duct to avoid puncture site infection caused by bile, and it was pulled out 4 d after ERCP. Then the patient was discharged from hospital without any symptoms. The hematoma had completely disappeared at 1 mo follow-up.

A duodenal hematoma is usually caused by trauma, anticoagulant therapy, rupture of a duodenal aneurysm or biopsy. A duodenal hematoma following ERCP is very rare[1-4]. Some studies reported that the guidewire was inserted into the liver capsule and caused bleeding beneath the liver capsule due to rupture of small vessels in the liver parenchyma. When it is difficult to insert a duodenoscope into the duodenum, the long route of the endoscope and abdominal pressure may cause hematoma in the peritoneal cavity[5,6].

The position of the duodenum is generally stationary. When it is compressed, the pylorus will close, and a close circuit is formed between the pylorus and Treiz ligament. The air pressure in the duodenum will be acutely increased, causing the rupture of vessels in the intestinal wall. In some cases, direct damage to the intestinal wall during the operation will cause the hematoma, and if not treated in time, it will result in intestine necrosis and perforation.

The diagnosis of IDH is likely if there are symptoms such as abdominal pain, vomiting and duodenal obstruction after ERCP[6]. Laboratory evaluations are non-specific and usually show only a mild decrease in hemoglobin concentration. Imaging techniques, including gastrointestinal endoscopy, CT and MRI, can be used to confirm the diagnosis. Gastrointestinal endoscopy can demonstrate not only duodenal obstruction, but also perforation. CT and MRI can determine the exact extent of the hematoma and may also indicate perforation[7,8]. Since perforation needs a surgical operation, imaging techniques have to be performed immediately.

Once IDH is confirmed, conservative management with fasting, total parenteral nutrition and nasogastric suction should be given promptly. Traditionally, a duodenal hematoma is mainly treated by open surgery drainage and PTCD[9], both causing great trauma. The method used in the present case is minimally invasive and has less risk. We would like to emphasize the following key points in our method. First, the opening should be made at the center of the hematoma with the needle knife under a duodenoscope, and the head of the drainage tube should be soft and flexible to avoid damage to the hematoma wall. Transnasal drainage can be performed by vacuum aspiration, which allows easy observation of the drainage volume. Secondly, after opening the hematoma, the catheter is introduced and the contents are extracted, and then a transnasal guidewire is placed for drainage. Thirdly, the opening on the hematoma should be clamped and an ENBD tube should be placed to drain the bile duct to avoid infection by bile and intestinal juice.

A duodenal hematoma is a rare complication of ERCP, and blunt damage by the endoscope and an accessory should be avoided during ERCP. A CT scan shows specific signs of ERCP-associated duodenal hematoma, such as a high density mass in the enteric cavity and a narrowed enteric cavity. A duodenal hematoma can be easily diagnosed by endoscopy. When the hematoma is very big or causes obstruction of the intestine, a drainage tube can be used to aspirate the contents of the hematoma. Transnasal drainage combined with needle knife puncture under endoscopy has less injury risk and is easy to perform, making it superior to percutaneous drainage. Since ERCP has become a common approach for the treatment of biliary and pancreatic diseases, the incidence of IDH is likely to increase. Our method is worth popularizing in clinical practice.

| 1. | Wang JY, Ma CJ, Tsai HL, Wu DC, Chen CY, Huang TJ, Hsieh JS. Intramural duodenal hematoma and hemoperitoneum in anticoagulant therapy following upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Med Princ Pract. 2006;15:453-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Guzman C, Bousvaros A, Buonomo C, Nurko S. Intraduodenal hematoma complicating intestinal biopsy: case reports and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:2547-2550. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Ghishan FK, Werner M, Vieira P, Kuttesch J, DeHaro R. Intramural duodenal hematoma: an unusual complication of endoscopic small bowel biopsy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:368-370. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Lipson SA, Perr HA, Koerper MA, Ostroff JW, Snyder JD, Goldstein RB. Intramural duodenal hematoma after endoscopic biopsy in leukemic patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:620-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | McArthur KS, Mills PR. Subcapsular hepatic hematoma after ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:379-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kwon CI, Ko KH, Kim HY, Hong SP, Hwang SG, Park PW, Rim KS. Bowel obstruction caused by an intramural duodenal hematoma: a case report of endoscopic incision and drainage. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24:179-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hayashi K, Futagawa S, Kozaki S, Hirao K, Hombo Z. Ultrasound and CT diagnosis of intramural duodenal hematoma. Pediatr Radiol. 1988;18:167-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Martin B, Mulopulos GP, Butler HE. MR imaging of intramural duodenal hematoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1986;10:1042-1043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gullotto C, Paulson EK. CT-guided percutaneous drainage of a duodenal hematoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:231-233. [PubMed] |

P- Reviewers Paspatis GA, Palma GD S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Xiong L