INTRODUCTION

It is recommended to visualize the second portion of the duodenum including the ampulla of Vater (AV) during a standard esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) procedure[1,2]. Adequate visualization of the AV is important for early detection of periampullary or pancreaticobiliary diseases[3,4].

EGD textbooks and guidelines have emphasized complete visualization of the AV[1,2], but at the same time indicated that complete visualization of the AV is difficult due to the anatomical characteristics of the second portion of the duodenum, including the tangential angle, the periampullary diverticulum, and loop formation in the scope[5]. Thus, a side-viewing endoscope has been recommended for complete visualization of the AV in patients with a suspected AV lesion or in whom the AV cannot be observed completely. However, a side-viewing endoscope is not always available in an ordinary endoscopy suite[6]. So clinicians should refer the patient for side-viewing endoscopy. In the case of South Korea, 4.2 million EGDs being performed as a screening test per year. Among them, 84% were performed in clinics that not equipped with side-viewing endoscope[6]. And, although tertiary referral center were equipped with side-viewing endoscope, the Health Promotion Center for screening test were separated from Hospital Endoscopy Center for inpatient. So many endoscopists for screening test are not familiar with side-viewing endoscope for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Therefore an additional examination using a side-viewing endoscope is expensive, time-consuming and difficult.

Cap-assisted endoscopy (CAE) has been used widely to facilitate detection of polyps[7-10], improve the success rate of cecal intubation[11,12], and to facilitate inspection of lesions situated in blind areas of the colon[13-15]. We have found that the complete visualization rate of the AV in patients who are referred for incomplete visualization of the AV can be improved by attaching a transparent cap. Therefore, we conducted a prospective observational study to investigate the complete visualization rate of the AV during routine EGD and to evaluate the efficacy and safety of endoscopic examination using a transparent cap to completely visualize the AV in patients in whom this procedure failed with a conventional endoscope.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

A prospective study was conducted on 120 patients > 20 years of ages who visited the Health Promotion Center of Chungbuk National University Hospital for conscious sedation EGD as a screening test from July to October, 2011. The following patients were excluded from the study: (1) those with poor general condition who had an American Society of Anesthesiology classification ≥ 3; (2) those who received previous upper gastrointestinal tract surgery or ERCP; and (3) patients with severe comorbidities. All patients provided written informed consent to participate in the study. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chungbuk National University Hospital (D-2011-06-006).

Procedure

All examinations were conducted with the patient lying on their left side, and midazolam was administered as a sedative and pain medication. Approximately 30-40 mg of propofol was also administered depending on patient weight[16]. Additional administration of propofol was used when deemed necessary, according to procedure time. Heart rate and oxygen saturation were checked in real time. Demographic data, procedure time, visualization of the AV, and complications were recorded. All examinations were carried out with a forward-viewing endoscope (GIF 230; Olympus Optical Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) by a well-qualified endoscopist (Han JH), who has conducted more than 1500 EGDs including 400 ERCPs annually. Two types of transparent caps were used: disposable distal attachments; “soft and short” cap (D-201-10704, outer diameter: 11.35 mm, length from distal end of endoscope: 4 mm. Olympus Medical Systems) and a “hard and long” cap (MH-593, outer diameter: 12.9 mm, length from distal end of endoscope: 11 mm; Olympus Medical Systems) (Figure 1).

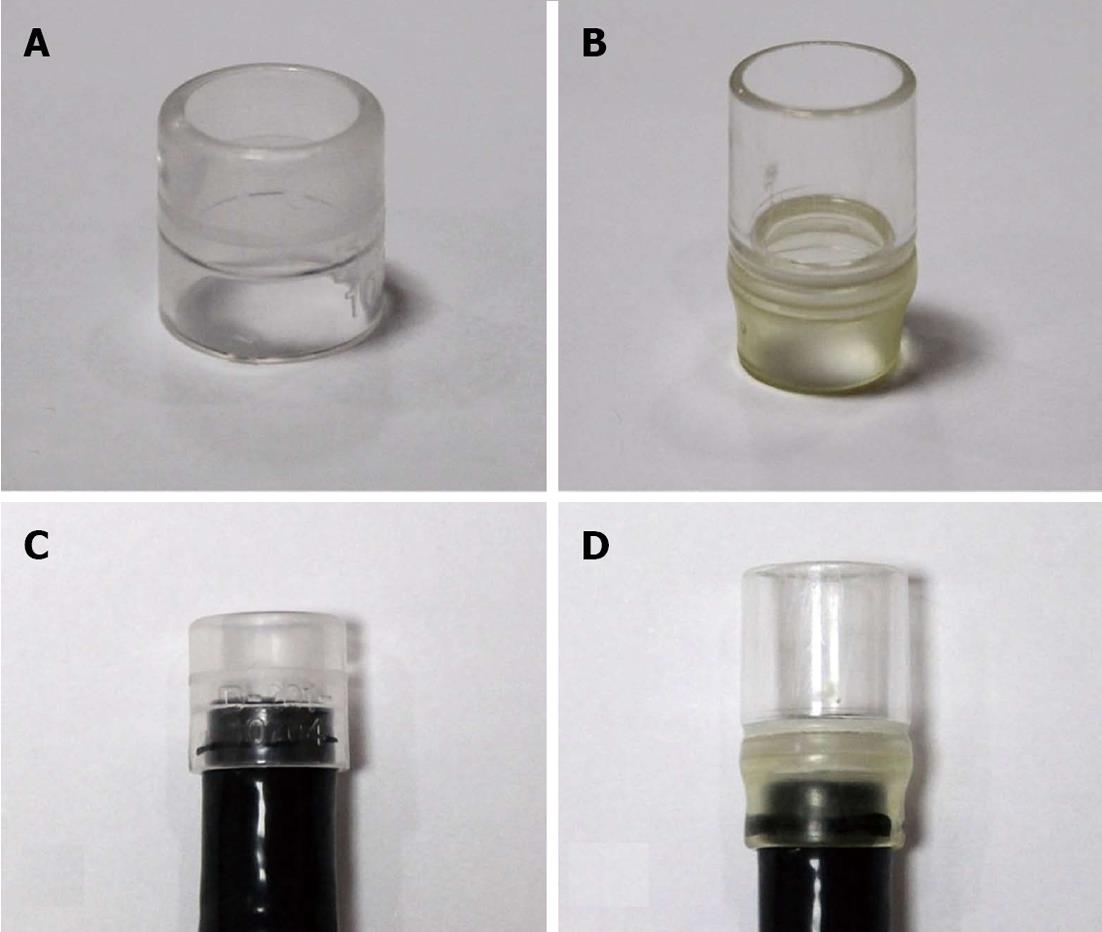

Figure 1 Endoscopic transparent cap.

A: Short transparent cap (Olympus distal attachment D-201-10704, outer diameter: 11.35 mm, length from distal end of endoscope: 4 mm; Olympus Tokyo, Japan); B: Long transparent cap (Olympus distal attachment MH-593, outer diameter: 12.9 mm, length from distal end of endoscope: 11 mm; Olympus); C: Short cap attached to the tip of a forward-viewing endoscope; D: Long cap attached to the tip of a forward-viewing endoscope.

First, forward-viewing endoscopy was performed with reasonable effort using a push and pull method. We considered complete visualization of the AV when we could observe the entire AV including the orifice clearly, and reported the observation as complete or incomplete (partial or not found at all). Second, in cases of complete failure of the observation, an additional AV examination was conducted by attaching a short cap to the tip of a forward-viewing endoscope. Third, if the second method failed, we replaced the short cap with a long cap and performed a re-examination of the AV.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software, version 12.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, United States), and frequency, percentage, mean, and range were used for descriptive analyses. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patients’ characteristics and outcomes of conventional endoscopy

A total of 181 patients were examined, 61 were excluded. 120 patients were enrolled and agreed to participate in the study by signing an informed consent (Figure 2). Conventional endoscopy achieved complete visualization of the AV in 97 of the 120 patients (80.8%) but was not achieved in 23 patients (19.2%) (Figure 3). The reasons for failure to visualize the ampulla were large fold in 16 patients, and diverticulum in 7 patients. Age (mean ± SD) and gender [male (%)] were not significantly different between the complete observation and the incomplete observation groups [55.3 ± 12.6 years, 59 (60.8%); 55.2 ± 16.2 years, 12 (52.2%)], respectively.

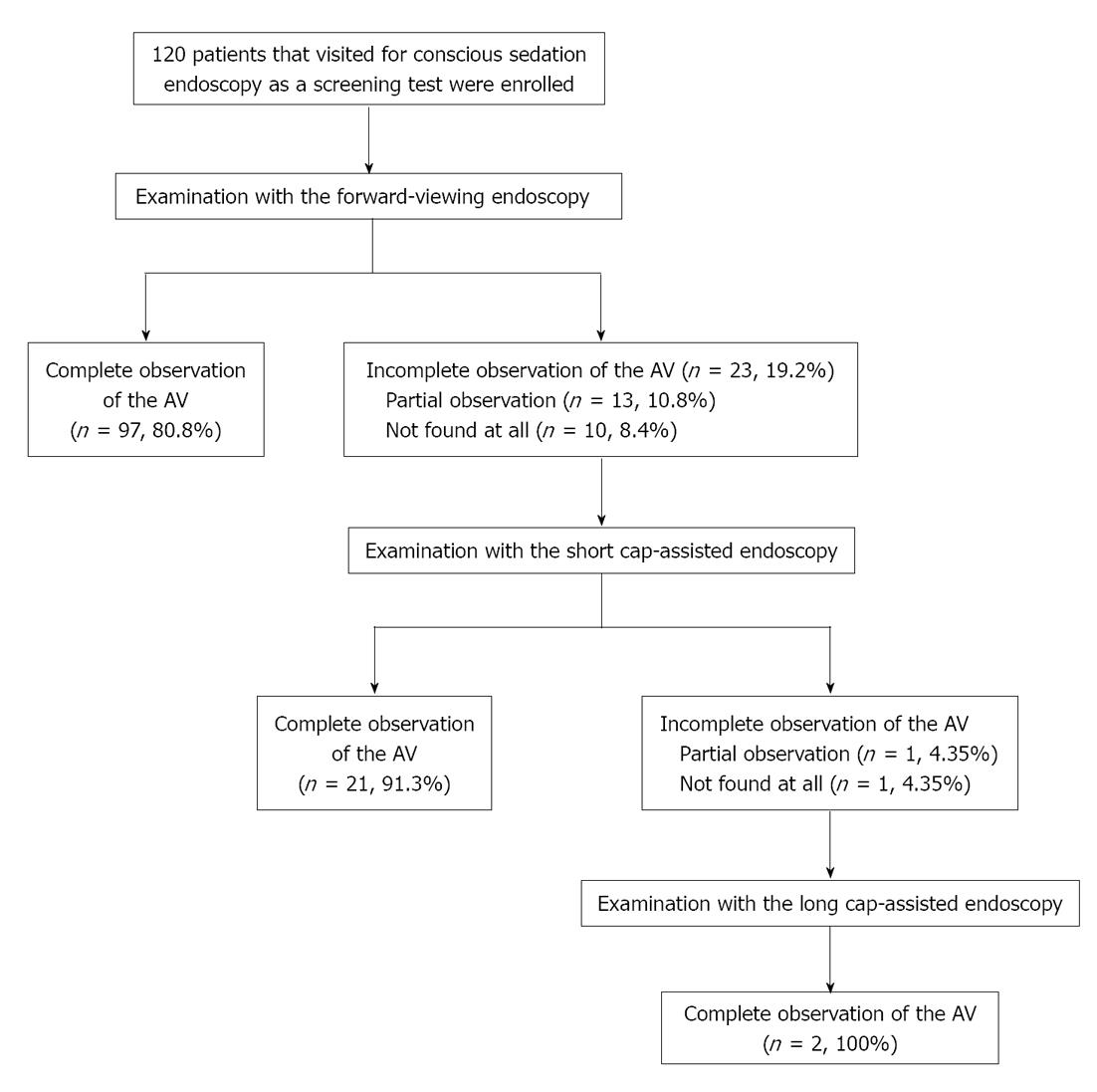

Figure 2 Flow diagram of patient enrollment and examinations.

In total, 120 patients were examined by forward-viewing endoscopy. In cases when complete observations of the ampulla of Vater (AV) were unsuccessful, an additional examination for the AV was conducted by short cap-assisted endoscopy. If that examination was unsuccessful, the short cap was replaced with a long cap, and a re-examination was performed.

Figure 3 Outcomes of conventional endoscopy.

A: Complete observation of the ampulla of Vater (AV), including the orifice, by forward-viewing endoscopy; B: Partial observation of the AV with a folded mucous membrane by forward-viewing endoscopy; C: The AV was not found during forward-viewing endoscopy.

Outcomes of CAE

Additional short CAE was performed in patients in whom we could not completely visualize the AV. This group included 13 patients (10.8%) with partial observation of the AV and 10 (8.4%) in which the AV was not found. Short CAE permitted a complete observation of the AV in 21 of the 23 patients (91.3%).

In cases of an incomplete visualization due to folded mucous membranes, complete observation of the orifice areas was achieved by uncovering the fold with a short cap (Figure 4A and B). Due to a too close proximity of the endoscope tip to the superior ampulla lesion, the short cap provided a proper distance and the ability to straighten the mucosal fold by pressing the area surrounding the lesion (Figure 4C and D). The cap made it easier to access the AV at the edge of the diverticulum by directing the force vector along the tip of the endoscope (Figure 4E and F). Patients in whom visualization of the AV failed with short CAE had satisfactory outcomes by replacing the short cap with a long cap; one AV was observed only partially due to the deep location of the AV in the large diverticulum, whereas the other was not found due to a loop in the scope (Figure 4G and H). The time for CAE was 141 ± 88 s. No complications or significant mucosal trauma occurred. In one case of suspected abnormal lesions, an additional side-viewing endoscopy with biopsy revealed a tubular adenoma, so an endoscopic ampullectomy was performed.

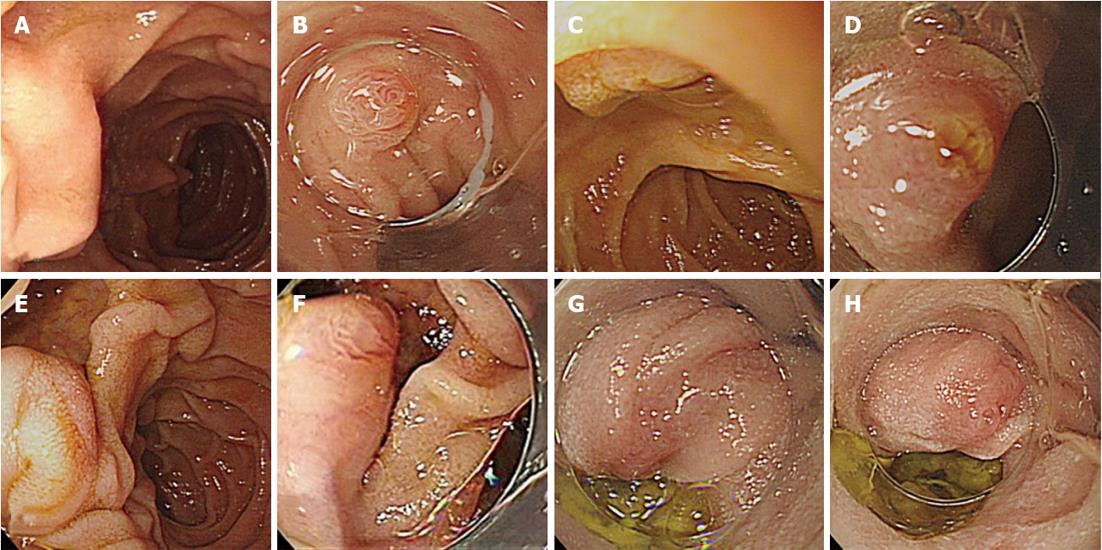

Figure 4 Incomplete observation of the ampulla of Vater by conventional endoscopy and outcomes of cap-assisted endoscopy.

A: Incomplete observation of the ampulla of Vater (AV) by forward-viewing endoscopy due to a folded mucous membrane; C: Incomplete observation of the AV due to the close proximity of the endoscope tip to a superior ampulla lesion; E: Incomplete observations of the AV on the edge of diverticulum; B, D, F: Complete observation of the AV, including the orifice, by short cap-assisted endoscopy (A→B, C→D, E→F); G: Incomplete observation of the AV by short cap-assisted endoscopy due to a loop in the scope; H: Complete observation of the AV by long cap-assisted endoscopy (G→H).

DISCUSSION

The transparent cap was first proposed in 1990 by Inoue et al[17] to improve the accessibility of the forward-viewing endoscope. Since then, transparent CAE has been used widely as a method to increase the success rate of the procedure[18,19]. For example, CAE improves cecal intubation times and polyp detection rates during colonoscopy[9,11], it achieves higher success rates of afferent loop intubation and bile-duct cannulation in patients with a Billroth II gastrectomy[20-22], and it possible to clip a lesion too tangential to be clipped by routine endoscopy[23-27].

Although there is a growing need to identify CAE as an effective approach to visualize the AV, no studies have investigated the AV observation rate during routine EGD or the efficacy of CAE for AV observation. Although small studies (preliminary data of Leal-Salazar et al[28] described the feasibility of visualizing the AV by attaching a long cap from a variceal band ligation set to a conventional endoscope) have been conducted, almost all cases (19 of 20) required emergency endoscopic hemostasis treatment, were not for screening test. That study reported conventional endoscopy permitted an inadequate observation of the AV in all cases (20 of 20), which is questionable, although they reported that observations of the AV using CAE were effective.

Although our cases had a wide variation in procedure duration, complete visualization of the AV was possible in up to 100% by attaching a cap to the tip of a conventional endoscope. The additional time for this procedure was short (average, 141 s). Moreover, the AV could be visualized completely in almost all patients using short CAE. Although a long cap has been used widely, the long cap is hard and difficult to pass over the larynx and pylorus, so it is easy to damage the mucosa, whereas the short cap is soft, safer, and relatively simple and easy to handle.

The transparent cap made the following multiple mechanisms possible: (1) The transparent cap provided a proper distance between the AV and the tip of the endoscope, which may prevent sticking of the endoscope to the duodenal lumen; (2) The cap allowed efficient manipulation of a tangentially placed AV to a more square approach; (3) The cap made it easier to access hidden areas by straightening the mucosal folds by pressing the surrounding lesion areas; and (4) the cap reduced loop formation by “hooking” the tip of the endoscope in the second portion of the duodenum and directing the force vector of the endoscope tip[29-33]. Moreover, the long cap improved all of these functions; thus, it allowed an approach to a deeply AV located deepin the diverticulum[34-36].

This study had some limitations. First, data collection was limited to screening tests in a healthy population that visited the Health Promotion Center; these patients can have lower disease prevalence or anatomical variations in the AV than those in the general population. Thus, the success rate of CAE may be different in the general population. Second, because EGD was performed by one ERCP expert, the results cannot be generalized to a conventional endoscopist with less experience visualizing the AV.

In conclusion, CAE was an effective salvage technique when regular EGD was ineffective for visualizing the AV properly. CAE can increase the diagnostic accuracy of a forward-viewing endoscope and decrease the need for side-viewing endoscopy.

COMMENTS

Background

Adequate visualization of the ampulla of Vater (AV) is important for early detection of periampullary or pancreaticobiliary diseases. But visualization of the AV with a forward-viewing endoscope is difficult due to the anatomical characteristics of the second portion of the duodenum. Thus, a side-viewing endoscope has been recommended for complete visualization of the AV. However, a side-viewing endoscope is not always available in an ordinary endoscopy suite.

Research frontiers

Cap-assisted endoscopy (CAE) has been used widely to facilitate detection of polyps, improve the success rate of cecal intubation, and to facilitate inspection of lesions situated in blind areas of the colon. The authors have found that the complete visualization rate of the AV in patients who are referred for incomplete visualization of the AV can be improved by attaching a transparent cap.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Although there is a growing need to identify CAE as an effective approach to visualize the AV, no studies have investigated the AV observation rate during routine esophagogastroduodenoscopy or the efficacy of CAE for AV observation. This is the first study to determine the efficacy and safety of an endoscopic examination using a transparent cap to completely visualize the AV in patients failed by conventional endoscopy.

Applications

CAE can increase the diagnostic accuracy of a forward-viewing endoscope and decrease the need for side-view endoscopy. This study may represent a future strategy for effective endoscopic examination as a screening test.

Terminology

Endoscopic caps are commonly used for both diagnosis and therapy during endoscopy. Transparent caps are attached to the distal end of the endoscope. Currently, many different sized caps are available. Cap-assisted endoscopic mucosal resection is the most common application of endoscopic caps. The appropriate selection of an endoscopic cap based on indication and location of the lesion is important for procedural success.

Peer review

The authors examined the efficacy of a CAE to completely visualize the AV in patients failed by conventional endoscopy. It revealed that CAE can increase the diagnostic accuracy of a forward-viewing endoscope and decrease the need for side-view endoscopy. The result are interesting and promising for endoscopic examination as a screening test.