INTRODUCTION

Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL) is a rare gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, originating from intraepithelial T lymphocyte, which is strongly related with celiac disease[1]. Due to its scarcity, EATL is accounted for less than 1% of all non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas category, which primarily involves the small bowel[2]. EATL has generally poor prognosis with high mortality rate. World Health Organization classified two types of EATL, defined as type I EATL, which comprises 80%-90% and type II EATL, a monomorphic variant[3]. We have experienced the first case of EATL type II involving the whole tract of the colon in South Korea that was initially misdiagnosed as enterocolitis, resulting in the fatal colon perforation.

CASE REPORT

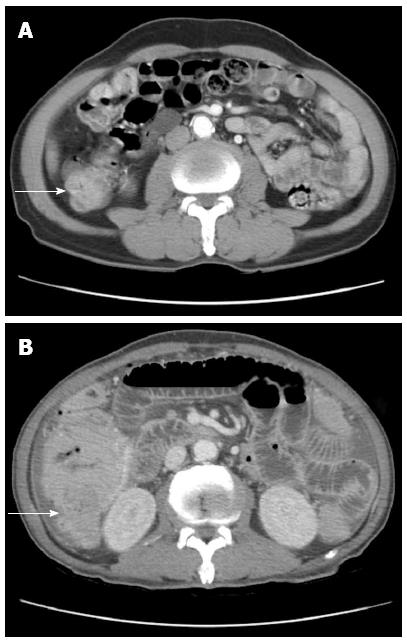

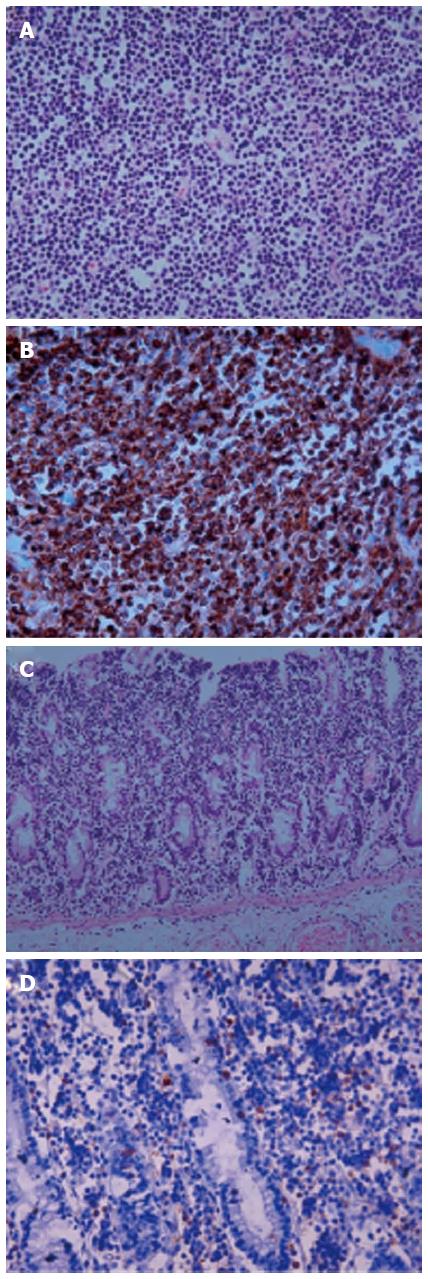

A 71-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with persistent diarrhea and abdominal pain for the past 6 mo. At that time, his abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed segmental wall thickening of distal ascending colon with nonspecific multiple small lymph nodes along the ileocolic vessels with colonoscopic findings, which revealed normal mucosa in the entire colon (Figure 1A). He continued to have diarrhea and diffuse abdominal pain when he arrived at our institution. He had chronic ill-looking appearance with alert mental status. The initial vital signs checked were normal, with increased bowel sound and right lower quadrant area tenderness. The laboratory findings revealed white blood cell count 3840/mm3, Hb 9.3 g/dL, and Plt 134 × 103/mm3 with peripheral blood morphology, showing normocytic normochromic anemia. In liver chemistry, aspartate aminotransferase was increased to 61 IU/L, and C-reactive protein check 6.4 mg/dL. A plain abdominal radiography showed paralytic ileus in the large-bowel with gaseous distention. With the supportive treatment, abdominal symptoms and follow-up abdominal X-ray showed gradual improvement. He was discharged after one week of admission; however, few hours after the discharge, he revisited to emergency room with sudden onset of acute abdominal pain with high fever and drowsy mental status. Patient assumed to be at septic shock condition with blood pressure measuring 60/40 mmHg, heart-rate 104/min, respiration 27/min, and body temperature 39.7 °C. Plain abdomen radiography revealed free air on the diaphragm, which indicated the perforation of the intestine. Abdomen CT scan showed large irregular masses on the right ascending colon and the hepatic flexure was seen with hydropneumoperitoneum, indicating colon cancer perforation (Figure 1B). Also, multiple enhanced enlarged lymph nodes were found in pericolic, right iliac chain, preaortic, portal hepatis and peripancreatic area, suggesting metastatic lesions. Emergent right hemi-colectomy of large bowel was performed, and post-operative gross findings from the resected tumor showed 9 cm × 7 cm × 3 cm size mass in the ascending colon extension to serosa layer, without the invasion to the adjacent area (Figure 2). Histologic findings showed tumor cells diffusely infiltrating the whole intestinal mucosa, involving the resection margins of the terminal ileum to the colon. The lymphoma cells were small to medium-sized, with round, hyperchromatic nuclei, having a stippled chromatin pattern. Immunohistochemical staining of the tumor cells expressed CD56 and positive for CD3 and CD8 intraepithelial lymphocytes, but negative for CD20 and Epstein-Barr virus. The adjacent mucosa showed heavy lymphoid infiltrate invading in all layers of the colon layer (Figure 3). The final diagnosis confirmed type II EATL.

Figure 1 An abdominopelvic computed tomography shows segmental wall thickening of distal ascending with nonspecific multiple small lymphnodes along ileocolic vessels.

Large irregular mass (A) in right ascending colon along hepatic flexure (B).

Figure 2 A gross specimen from the ascending colon after right hemicolectomy.

In perforated site, there is an ulcero infiltrative mass measuring 9 cm × 7 cm × 3 cm which is 13 cm away from ileocecal valve and distal resection margin, respectively. The tumor is grayish tan, fish-fresh and appears to extend to serosa.

Figure 3 Histologic features in enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma type II.

A: The lymphoma cells are small to medium-sized with round, hyperchromatic nuclei (x 400); B: The cells express CD56 (x 400); C, D: The adjacent mucosa shows heavy lymphoid infiltrate (x 200) (C) and CD8 positive intraepithelial lymphocytes (x 400) (D).

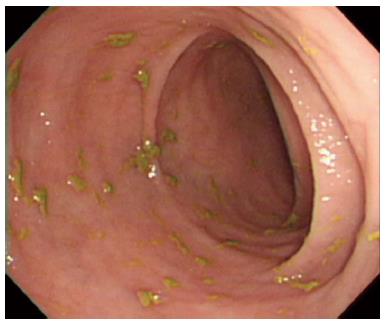

Two weeks after the operation, the follow up colonoscopy revealed normal mucosa and several random multiple biopsies were made in the entire colon (Figure 4). Histologic findings re-confirmed type II EATL. We recommend the treatment of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone chemotherapy to increase the chances of survival; however, he refused and wanted to go to a hospice facility near his hometown. He was transferred out and expired 3 d after the discharge from our institution.

Figure 4 Colonoscopy revealed normal mucosa pattern in whole colonic tract.

DISCUSSION

Reports on the diffuse involvement of EATL type II are a rare finding, as described in this report. Recent retrospective study conducted by Asia Lymphoma Study Group have shown a few case series of EATL arising from an Asian population, site involving the whole colonic tract have not been reported yet. However, pathologic features of type II EATL from Asian population were very different from those of classical EATL[4].

Due to the absence of specific symptoms, EATL is often diagnosed after the intestinal perforation or obstruction, which makes it more difficult to give proper initial treatment. As reported in our case, the patient had an acute onset of lower abdominal pain, without other associated symptoms, and colonoscopic findings were normal with non-specific findings on radiologic studies. A similar case was reported recently on 39-year-old African-American male, who was diagnosed with EATL after emergent exploratory laparotomy[5]. Among gastrointestinal tumors, primary gastrointestinal lymphomas comprise of 5%-10% of all non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and EATL accounts for less than 1% of all non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma[6]. The prevalence of the annual incidence of EATL is 0.5-1 per million people in Western countries[7]. WHO classified the two types of EATL: Type I EATL more often arising in areas with the high prevalence of celiac disease, while type II EATL seen in regions where celiac disease prevalence is rare. Sharaiha et al[8] reported that type I EATL is significantly increasing in the United States with close relation to celiac disease steadily rising every year. On the contrary, gluten sensitive celiac disease is rare in South Korea with very low prevalence[9]. The immunophenotype of type II EATL show distinctive pattern, in which the tumor cells are positive in CD3, CD8+, CD56+ and TCRβ+ and the intraepithelial lymphocytes in the adjacent mucosa share the identical immunophenotype[10]. The neoplastic cells have medium-sized, round, darkly staining nuclei, with a rim of a _ENREF_7 pale cytoplasm[11]. There has been interesting case report by Okumura et al[12] on the unusual type II EATL with MYC translocation in a Japanese patient, recently. As shown in our case, immunohistochemistry confirmed us to diagnose EATL and its subtype, rather than imaging study or colonoscopy. Therefore, it is crucial to require adequate biopsy and immunophenotyping to give early diagnosis and treatment to patients. With the introduction of a double balloon enteroscopy in 2003, diagnosis of celiac disease has been significantly advanced by non-surgical modalities[13]. And a recent study on the usefulness of diagnostic 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (18F-FDG-PET) in distinguishing between the sites of lymphoma and refractory celiac disease over CT showed better sensitivity and specificity[14]. Also, there was a case report using a capsule endoscopy to detect EATL involving the small bowel[15]. As described above, double ballon enteroscopy, 18F-FDG-PET and capsule endoscopy might be all useful options to detect EATL in advanced to increase survival of patients. One-year survival rate of the intestinal T-cell non-Hodgkin’s disease is 33%, and five-year survival to be 9%[16]. The prognosis of EATL is more decimating; when treated with surgery and/or systemic chemotherapy, 80%-84% of patients die with a 5-year survival rate of 3.2%. Chemotherapy seems to be more beneficial to patients rather than surgery; however, there is no difference in the outcome between patients with type I and type II EATL[17].

Our patient had chronic abdominal symptoms with normal colonoscopic findings. Diagnostic tools, such as plain abdominal X-ray, CT and colonoscopy findings were not effective to diagnose EATL in advance. And considering that most of colonoscopists do not perform a biopsy if mucosa shows normal pattern, this may delay from an early discovery of EATL.

In summary, we report a unique case of diffuse involvement of type II EATL of colon with perforation, who was presented with non-specific radiological findings. Therefore, we emphasize the need of a random biopsy or capsule endoscopy to diagnose EATL early. Due to the disease appearance resembling features of colitis, careful attention should be made to reveal its obscure clinical manifestations, and physicians should be aware to conduct through physical examination and adequate biopsy to rule out EATL _ENREF_10.