Published online Mar 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i10.1657

Revised: December 11, 2012

Accepted: January 17, 2013

Published online: March 14, 2013

Processing time: 117 Days and 19.7 Hours

A 23-year-old male presented with a three-week-history of crampy abdominal pain and melaena. Colonoscopy revealed a friable mass filling the entire lumen of the cecum; histologically, it was classified as perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa). An magnetic resonance imaging scan showed, in addition to the primary tumor, two large mesenteric lymph node metastases and four metastatic lesions in the liver. The patient underwent right hemicolectomy and left hemihepatectomy combined with wedge resections of metastases in the right lobe of the liver, the resection status was R0. Subsequently, the patient was treated with sirolimus. After 4 mo of adjuvant mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition he developed two new liver metastases and a local pelvic recurrence. The visible tumor formations were again excised surgically, this time the resection status was R2 with regard to the pelvic recurrence. The patient was treated with 12 cycles of doxorubicin and ifosfamide under which the disease was stable for 9 mo. The clinical course was then determined by rapid tumor growth in the pelvic cavity. Second line chemotherapy with gemcitabine and docetaxel was ineffective, and the patient died 23 mo after the onset of disease. This case report adds evidence that, in malignant PEComa, the mainstay of treatment is curative surgery. If not achievable, the effects of adjuvant or palliative chemotherapy are unpredictable.

- Citation: Scheppach W, Reissmann N, Sprinz T, Schippers E, Schoettker B, Mueller JG. PEComa of the colon resistant to sirolimus but responsive to doxorubicin/ifosfamide. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(10): 1657-1660

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i10/1657.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i10.1657

Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) are rare mesenchymal neoplasms for which, according to a World Health Organization classification, histologically and immunohistochemically distinctive perivascular epithelioid cells are diagnostic[1]. Clinical courses are highly variable from benign behaviour to aggressive local tumor growth and seeding of metastases[2]. In this case report, a highly malignant type of PEComa in a 23-year-old male and its response to multimodal therapies is described.

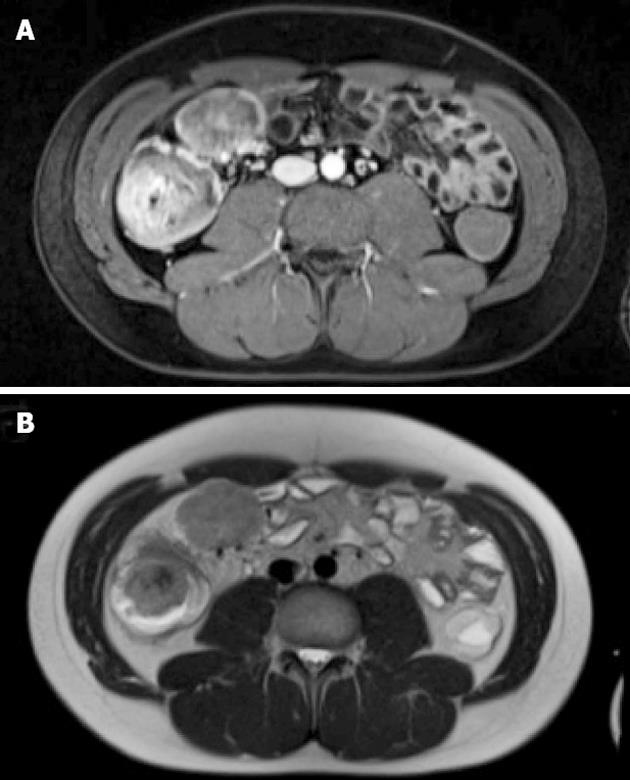

A 23-year-old male was admitted to the hospital because of crampy abdominal pain and melaena for three weeks. Colonoscopy revealed a 5.5 cm mass lesion in the cecum surrounding the ileocecal valve (Figure 1). At biopsy, the friable tumor tissue was bleeding easily. An magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showed, in addition to the primary tumor, two mesenteric lymph node metastases (each 5 cm in diameter) and 4 metastatic lesions in the liver (1-2 cm in diameter, segments 1, 2, 4a and 6) (Figure 2). Additional staging procedures at the time of primary diagnosis [abdominal and chest computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography] revealed no further tumor manifestations.

In a two-stage procedure, the patient underwent right hemicolectomy and, after recovery, left hemihepatectomy combined with atypical wedge resections of hepatic segments 1 and 6 (resection status R0). On the basis of biopsy and resection material, a diagnosis of malignant PEComa was made (see below).

Owing to the aggressive nature of the tumor, both clinically and histologically, the patient received adjuvant treatment with the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor sirolimus (2 mg/d). However, after 4 mo the drug had to be discontinued due to two new liver metastases in segments 7 and 8 which were removed by atypical wedge resection. Simultaneously, a local pelvic recurrence of 13 cm × 12 cm × 8 cm with bilateral ureteral obstruction and rectal impression was diagnosed. A debulking operation was performed which resulted in Hartmann’s situation (resection status R2); additionally, splints were inserted into both ureters.

Palliative chemotherapy with doxorubicin (75 mg/m2) and ifosfamide (5000 mg/m2) every 3 wk was started. This regime was well tolerated until cycle 7 when the dose had to be reduced due to hematotoxicity. Altogether, the patient received 12 cycles of doxorubicin/ifosfamide under which the disease was stable for 9 mo as evaluated by CT scans every 8-12 wk.

Afterwards renewed tumor growth in the pelvic cavity was observed, aggravated by malignant ascites. Three cycles of second line chemotherapy (gemcitabine 900 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 combined with docetaxel 100 mg/m2 on day 8 every 21 d) were administered without measurable effect. The patient died 23 mo after the onset of disease.

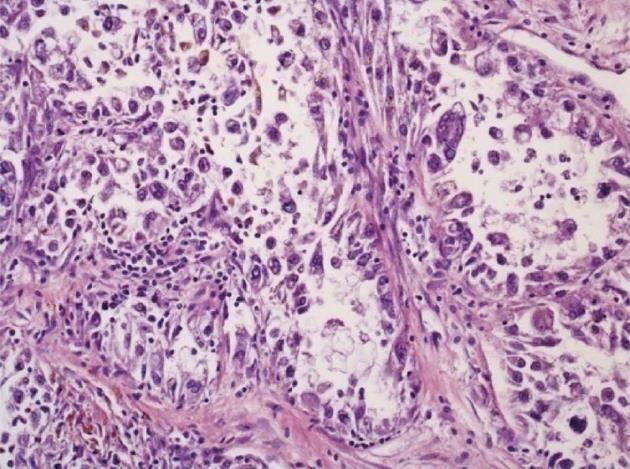

The specimen obtained at hemicolectomy showed a 5.5 cm measuring mass in the cecum with metastases in 2 of 18 regional lymph nodes, each measuring 5 cm in diameter. The tumor was located in the bowel wall, with broad ulceration of the overlaying mucosa. Histology (Figure 3) revealed a tumor of low to moderate cellularity, with a vague nodular pattern, an epithelioid and solid arrangement of the tumor cells and a sinusoidal vascular pattern without stromal desmoplasia. The tumor cells had a broad clear to granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, with moderate PAS positivity. The distinct cellular membranes exhibited some wrinkling. Most tumor nuclei showed moderate nuclear pleomorphism, but there were some highly pleomorphic hyperchromatic tumor cell nuclei. Sixty percent of the tumor area was necrotic. The mitotic rate was 12 per 10 high-power field (HPF). In some areas, the tumor was well demarcated, but there were other areas with a more infiltrative pattern of invasion.

Immunohistochemistry revealed positivity for HMB45 and negativity for melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 and microphthalmia-associated transcription factor. There was a weak expression of pankeratin markers (AE1/3, KL1) and CD56 in few tumor cells. Other markers (Synaptophysin, Chromogranin, PanLeu, CD34, CD31, S100, CD117, DOG1, Myogenin, MyoD1, EMA, Actin, Caldesmon, Desmin, CD30) were absent. Ki67 labeled 50%-60% of the tumor cells. PCR analysis of fresh frozen tumor material was negative for translocations suggestive of clear cell sarcoma [t(12;22)], synovial sarcoma [t(X;18)], myxoid liposarcoma [t(12;16)] and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma [t(2;13)].

The diagnosis of PEComa was suggested in the biopsies obtained at endoscopy. Because of the rarity of this tumor and the missing expression of smooth muscle markers usually found in PEComas, the tissue was sent to a reference pathologist (Fletcher CDM, Boston, MA, United States) who confirmed the diagnosis of PEComa. From the surgical material, a tumor area with brown cytoplasmic pigment (with negativity in the Prussion blue and PAS stains) was selected for electron microscopy; in this sample typical melanosomes could be demonstrated.

The tumor material obtained at the resection of liver metastases did not differ histologically from that of the primary tumor. However, following chemotherapy with doxorubicin/ifosfamide, there was a tremendous increase in nuclear pleomorphism with many extremely large hyperchromatic bizarre tumor nuclei, many tumor cells with nuclear fragmentation and micronuclei, and a decrease in the amount of mitotic figures. These morphologic alterations resemble regressive tumor changes following chemotherapy. However, the area of necrotic tumor cells was 20% at this time point, i.e. most of the tumor contained still viable cells.

This report of malignant PEComa has to be seen in the context of other single case descriptions or small case series on an extremely rare tumor entity. Predictors of prognosis in PEComa have been described in a clinicopathologic study on 26 cases by Folpe et al[3]: A significant association between tumor size > 5 cm, infiltrative growth pattern, high nuclear grade and cellularity, mitotic rate ≥ 1/50 HPF, necrosis, vascular invasion and subsequent aggressive clinical behaviour has been seen. In a more recent review article[4] on the basis of 234 PEComas the only pathologic factors of recurrence after surgical resection were primary tumor size ≥ 5 cm and a high mitotic rate of > 1/50 HPF. All of these “worrisome” pathologic features were present in the 23-year-old patient of the actual case. Additionally, the presence at initial diagnosis of two large metastases in mesenteric lymph nodes (each measuring 5 cm in diameter) and of 4 hepatic metastases had to be considered as clinical indicators of poor prognosis.

PEComas arise from various organs such as uterus and vagina, kidney, digestive tract, retroperitoneum, bone, skin and eye. Intestinal origins include stomach, colon and rectum, peritoneal cavity and falciform ligament. Considering only PEComas of the colon and rectum, there are 4 reports on 7 patients[5-8] in whom the clinical course was benign (5 × operation only, 2 × operation and adjuvant chemotherapy, no evidence of disease at the end of follow-up). These findings are in contrast with the actual case when mesenteric and hepatic metastases were present at the time of diagnosis. The organ of origin, therefore, does not seem to be a predictor of prognosis.

Concerning treatment strategies, Bleeker et al[4] stated that cytotoxic chemotherapy and radiation had shown little benefit in malignant PEComa. According to the authors, the emerging role of mTOR inhibitors would raise enthusiasm in the therapy of these rare tumors. The clinical course reported herein reflects the opposite impression: After R0 resection of the primary tumor and mesenteric/hepatic metastases, adjuvant mTOR inhibition with sirolimus given for 4 mo at a dose of 2 mg/d (suitable for liver transplant recipients) failed to prevent a local recurrence and new liver metastases. On the contrary, cytotoxic chemotherapy (doxorubicin/ifosfamide) considered first choice in soft tissue sarcomas was associated with stable disease for 9 mo. Thus, the combination of repetitive surgery with conventional chemotherapy may still be a choice in the palliative therapy of malignant PEComa. The benefit of mTOR inhibition (sirolimus, temsirolimus, everolimus), although theoretically attractive, is at present unpredictable[9,10]. Many other therapies have been tried to control unresectable PEComa, e.g., dacarbacine, epirubicin, paclitaxel, gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, imatinib, α-interferon, thalidomide, alone or in combinations. However, clinical outcomes have been extremely variable and a standard treatment is not in sight.

Some PEComas are associated with phakomatosis and hamartomatous diseases, e.g., the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). In these conditions the mTOR signalling pathway is activated which may thus be targeted by sirolimus and related compounds[11]. In the present case of the 23-year-old patient there was no indication of TSC. Due to the paucity of data it is unknown if the presence or absence of TSC can be used as a predictor of susceptibility to sirolimus therapy.

Given the extreme rarity and heterogeneity of PEComas, a comparative study with a focus on optimal treatment will unlikely be performed. Instead, a PEComa registry based at a sarcoma center would be a reasonable option. Well documented clinical courses, histological features and empirical therapies could thus be accumulated and best practice procedures deduced.

The support of Fletcher CDM, MD, Surgical Pathology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, in confirming the histological diagnosis and discussing therapeutic options is gratefully acknowledged. The authors thank Kuesters W, MD, Department of Radiology, Juliusspital Wuerzburg, for providing the MRI of Figure 2.

| 1. | Folpe AL. Neoplasms with perivascular epithelioid cell differentiation (PEComas). Pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. WHO classification of tumours. Lyon: IARC Press 2002; 221-222. |

| 2. | Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. PEComa: what do we know so far? Histopathology. 2006;48:75-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 341] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Folpe AL, Mentzel T, Lehr HA, Fisher C, Balzer BL, Weiss SW. Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms of soft tissue and gynecologic origin: a clinicopathologic study of 26 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1558-1575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 640] [Cited by in RCA: 666] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bleeker JS, Quevedo JF, Folpe AL. “Malignant” perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm: risk stratification and treatment strategies. Sarcoma. 2012;2012:541626. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Baek JH, Chung MG, Jung DH, Oh JH. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) in the transverse colon of an adolescent: a case report. Tumori. 2007;93:106-108. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Shi HY, Wei LX, Sun L, Guo AT. Clinicopathologic analysis of 4 perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas) of the gastrointestinal tract. Int J Surg Pathol. 2010;18:243-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Park SJ, Han DK, Baek HJ, Chung SY, Nam JH, Kook H, Hwang TJ. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) of the ascending colon: the implication of IFN-α2b treatment. Korean J Pediatr. 2010;53:975-978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ryan P, Nguyen VH, Gholoum S, Carpineta L, Abish S, Ahmed NN, Laberge JM, Riddell RH. Polypoid PEComa in the rectum of a 15-year-old girl: case report and review of PEComa in the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:475-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wagner AJ, Malinowska-Kolodziej I, Morgan JA, Qin W, Fletcher CD, Vena N, Ligon AH, Antonescu CR, Ramaiya NH, Demetri GD. Clinical activity of mTOR inhibition with sirolimus in malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumors: targeting the pathogenic activation of mTORC1 in tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:835-840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 269] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Subbiah V, Trent JC, Kurzrock R. Resistance to mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor therapy in perivascular epithelioid cell tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:e415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Plas DR, Thomas G. Tubers and tumors: rapamycin therapy for benign and malignant tumors. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:230-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewers Silverman JF, Finzi G S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L