Published online Mar 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i10.1632

Revised: January 10, 2013

Accepted: January 18, 2013

Published online: March 14, 2013

Processing time: 111 Days and 21.5 Hours

AIM: To investigate long-term outcome in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) after negative capsule endoscopy (CE) and identify risk factors for rebleeding.

METHODS: A total of 113 consecutive patients underwent CE for OGIB from May 2003 to June 2010 at Seoul National University Hospital. Ninety-five patients (84.1%) with a subsequent follow-up after CE of at least 6 mo were enrolled in this study. Follow-up data were obtained from the patients’ medical records. The CE images were reviewed by two board-certified gastroenterologists and consensus diagnosis was used in all cases. The primary outcome measure was the detection of rebleeding after CE, and factors associated with rebleeding were evaluated using multivariate analysis.

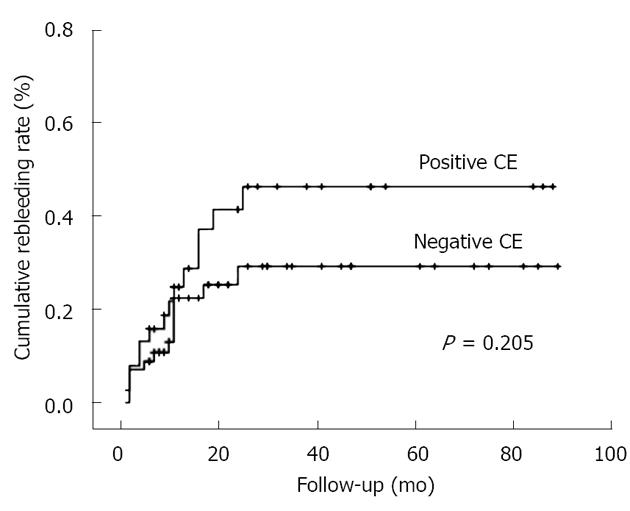

RESULTS: Of the 95 enrolled patients (median age 61 years, range 17-85 years), 62 patients (65.3%) were male. The median duration of follow-up was 23.7 mo (range 6.0-89.4 mo). Seventy-three patients (76.8%) underwent CE for obscure-overt bleeding. Complete examination of the small bowel was achieved in 77 cases (81.1%). Significant lesions were found in 38 patients (40.0%). The overall rebleeding rate was 28.4%. The rebleeding rate was higher in patients with positive CE (36.8%) than in those with negative CE (22.8%). However, there was no significant difference in cumulative rebleeding rates between the two groups (log rank test; P = 0.205). Anticoagulation after CE examination was an independent risk factor for rebleeding (hazard ratio, 5.019; 95%CI, 1.560-16.145; P = 0.007), regardless of CE results.

CONCLUSION: Patients with OGIB and negative CE have a potential risk of rebleeding. Therefore, close observation is required and alternative modalities should be considered in suspicious cases.

- Citation: Koh SJ, Im JP, Kim JW, Kim BG, Lee KL, Kim SG, Kim JS, Jung HC. Long-term outcome in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after negative capsule endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(10): 1632-1638

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i10/1632.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i10.1632

Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) represent about 5% of all gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage and is defined as recurrent or persistent bleeding or iron-deficiency anemia originating from the GI tract, with negative results from upper and lower endoscopy[1,2]. It has been reported that small-bowel hemorrhage is the most common cause for OGIB[3]. However, the difficulty in establishing a diagnosis in patients suspected of having small-bowel hemorrhage has made assessment of OGIB problematic, and diagnosis is often delayed. Recently, there have been advances in the identification of small-bowel hemorrhage using capsule endoscopy (CE) or balloon-assisted endoscopy.

CE is useful in the detection of the cause of small-bowel hemorrhage, and CE has a higher diagnostic yield than other diagnostic modalities[4-7]. In addition, CE has advantages over balloon-assisted endoscopy, in that CE allows observation of the whole small bowel and identification of the bleeding foci[8]. Furthermore, CE allows non-invasive viewing of the whole small-bowel mucosa. Most investigators, therefore, agree that CE should be the initial form of investigation for OGIB[3].

Several studies have evaluated the clinical implications of negative CE results over the long-term. However, there are contradictory findings regarding long-term outcome in patients with OGIB and negative CE results[9-11]. In addition, most of these studies comprise small numbers of patients and have short-term follow-up. Furthermore, it has been reported that significant small-bowel pathology may be missed during CE examinations, but can be subsequently diagnosed using alternative diagnostic tools including double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE)[12,13]. On the basis of these results, establishment of long-term clinical outcomes in patients with OGIB and negative CE remains unknown.

The aim of this study was to investigate the long-term outcomes in patients with OGIB and negative CE results and to identify the risk factors that are associated with rebleeding.

Between May 2003 and June 2010, a total of 113 consecutive patients at Seoul National University Hospital that had OGIB underwent CE to identify the cause of bleeding. Among those, long-term follow-up (> 6 mo) data were available for 95 (84.1%) patients. OGIB was defined as either obscure-overt (presented as melena or hematochezia) or obscure-occult (iron-deficiency anemia with or without positive fecal occult blood) GI bleeding. Patient enrollment required one or more non-diagnostic esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy examinations prior to CE. Clinical information and follow-up data were obtained from the patients’ medical records. The data included age, sex, comorbidity, anticoagulant use, aspirin use, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) use, hemoglobin level, and type of treatment for bleeding. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital.

CE was performed with the PillCam SB (Given Imaging, Yoqneam, Israel) or MiroCam (IntroMedic, Seoul, South Korea) CE system. After 12 h fasting, the capsule was taken by the patients. According to our unit’s protocol, bowel preparation was not performed. Patients were allowed to drink water 2 h after swallowing the capsule and to have a light meal 4 h later. The recorder was stopped at about 8 h or 12 h after swallowing the PillCam SB or MiroCam. Patients were advised to keep away from magnetic exposure until capsule excretion.

The CE images were reviewed by two board-certified gastroenterologists; consensus diagnosis was used in all cases. Inter-observer agreement was > 95%. The videos were read at a speed of 15 frames/s.

According to standard practice guidelines, CE findings were categorized into three types: lesions considered to have a high potential for OGIB (P2); lesions with uncertain bleeding potential (P1); and lesions with no bleeding potential (P0)[14,15]. Positive studies were defined as examinations that identified one or more P2 lesions, whereas those that identified only P1 or no abnormal lesions were regarded as negative results. Further evaluations such as abdominal computed tomography (CT), small-bowel follow-through, bleeding scan, or conventional angiography were performed in patients with persistent overt GI bleeding. However, because it was only introduced in our institution in September 2009, balloon-assisted endoscopy was only performed in four patients who had positive CE findings. Patients who showed minor OGIB without recurrence were carefully observed without further evaluation.

Each patient’s subsequent management was decided according to their CE results and clinical conditions. Specific treatment was performed in patients with identifiable causes on CE or with persistent overt bleeding, which included endoscopic, angiographic or surgical hemostasis; discontinuation of anticoagulants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, or other antiplatelet agents; steroids for patients with Crohn’s disease; and anti-tuberculosis medication for patients with tuberculosis enterocolitis. Red blood cell (RBC) transfusion, iron supplementation, or watchful waiting, which were classified as non-specific treatments, were performed in patients with negative CE after minor OGIB.

The primary outcome measure was the detection of rebleeding after CE. Rebleeding was defined as evidence of GI bleeding at least 30 d after the initial bleeding. Evidence of GI bleeding was defined as overt bleeding (melena or hematochezia) or a fall in hemoglobin value of ≥ 2 g/dL compared with the baseline value, and in the absence of other causes of decline in hemoglobin level[10]. Secondary outcome measures were the rate of transfusion and subsequent hospitalization after CE.

Univariate analyses were performed using Student’s t test for continuous variables and the χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. A Kaplan-Meier curve with a log rank test was used to analyze the cumulative rebleeding rates. Multivariate analysis was done by using the Cox proportional hazards model to identify the risk factors associated with rebleeding. Statistical significance was determined using a P value < 0.05. All analyses were carried out using SPSS for Windows version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

Ninety-five patients who had undergone CE, with subsequent follow-up of > 6 mo within the defined period were studied. The baseline characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. The median age was 61.0 years (range 17-85 years) and 62 patients (65.3%) were men. Seventy-three (76.8%) underwent CE for obscure-overt GI bleeding. Complete small-bowel visualization was achieved in 77 patients (81.1%). The median follow-up period was 23.7 (range 6.0-89.4) mo after CE. The majority of patients had undergone additional diagnostic workup, which included abdominal CT (61.1%, 58/95), small-bowel follow-through (21.1%, 20/95), RBC scan (14.7%, 14/95), and conventional angiography (9.5%, 9/95).

| Characteristics | Total (n = 95) |

| Age (yr), median (range) | 61.0 (17-85) |

| Male | 62 (65.3) |

| Obscure-overt bleeding | 73 (76.8) |

| Complete small-bowel visualization | 77 (81.1) |

| Comorbidity | 43 (45.3) |

| Hemoglobin concentration at the time of the procedure (g/dL), mean ± SD | 8.3 ± 2.0 |

| Need for transfusion before capsule endoscopy | 50 (52.6) |

| Diagnostic yield | 38 (40.0) |

| Follow-up duration (mo), median (range) | 23.7 (6.0-89.4) |

| > 12 mo follow-up | 73 (76.8) |

| Aspirin use | 23 (24.2) |

| Other antiplatelet agent | 13 (13.7) |

| Anticoagulation | 8 (8.4) |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 10 (10.5) |

The CE results are summarized in Table 2. Thirty-eight (40.0%) patients had a significant abnormality that showed as one or more P2 lesions. These included erosion or ulcer (21.1%, 8/38), angiodysplasia (26.3%, 10/38), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) including tuberculosis enteritis (23.7%, 9/38), small-bowel tumors (5.3%, 2/38), and active bleeding of unknown origin (23.7%, 9/38). There was no significant difference in the prevalence of positive findings according to the initial manifestation (P = 0.921), with 29 of 73 patients with overt GI bleeding showing a positive CE result (39.7%), compared to 9 of 22 patients with occult bleeding showing a positive CE result (40.5%).

| Findings | Total (n = 95) | Specific treatment | Rebleeding |

| P2 lesion | 38 | 24 (63.2) | 14 (36.8) |

| Ulcer or erosion | 8 | 6 (75.0) | 3 (37.5) |

| Tumor | 2 | 2 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Angiodysplasia | 10 | 3 (30.0) | 4 (40.0) |

| Bleeding from unknown focus | 9 | 4 (44.4) | 4 (44.4) |

| IBD including tuberculosis enteritis | 9 | 9 (100) | 3 (33.3) |

| P1 lesion | 6 | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) |

| Erosion | 2 | 0 (0) | 1 (50.0) |

| Non-bleeding polyp | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Lymphangiectasia | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| P0 lesion | 51 | 3 (5.9) | 12 (23.5) |

| Total | 95 | 27 (28.4) | 27 (28.4) |

Of the 38 patients with positive CE results, 24 received specific treatments. Conservative management such as iron replacement, watchful waiting, or blood transfusion was performed in 14 patients. Of the 10 patients with angiodysplasia, argon plasma coagulation (APC) was performed in three. The rebleeding rate was higher in patients treated with APC (66.7%, 2/3) than in those undergoing conservative management (28.6%, 2/7). In eight patients with small-bowel ulcer or erosion, one patient with multiple ulcers was considered to have involvement of myeloproliferative disease, which was treated with systemic chemotherapy. Five patients discontinued NSAID use. Two patients with small-bowel tumor underwent surgical resection; their tumors were histologically diagnosed as GI stromal tumor and an inflammatory fibroid polyp, respectively. Of the nine patients classified in the IBD group, including Crohn’s disease and tuberculosis enterocolitis, all were treated with steroids or anti-tuberculosis medication. Of the four patients who had active bleeding without identifiable cause, one was treated with explorative laparotomy and diagnosed with radiation enterocolitis. One patient was confirmed with Crohn’s disease after performing balloon-assisted endoscopy. One patient was also confirmed with early stage Crohn’s disease that involved the terminal ileum and cecum, after performing colonoscopy and biopsy. Finally, one patient was diagnosed with angiodysplasia of the duodenum and treated with APC.

Of the 51 patients with negative CE, rebleeding was identified in 12, and nine of these patients underwent additional evaluation for recurrent overt GI bleeding. The evaluation included abdominal CT, small-bowel follow-through, RBC scan, Meckel’s scan, and explorative laparotomy. Despite these examinations, the focus of significant bleeding was not detected in six patients. However, significant small-bowel lesions were detected in three patients. In one of these, a bleeding diverticulum arising from distal ileum was identified on CT angiography and treated with angiographic embolization. In another, an ulcer was identified in the distal ileum using small-bowel follow-through. That lesion was confirmed with extranodal marginal zone lymphoma after explorative laparotomy. In the last case, jejunal angiodysplasia was identified as the focus of the recurrent bleeding through explorative laparotomy with intraoperative enteroscopy. The remaining three patients who showed recurrent occult bleeding and had negative CE results received symptomatic treatment including iron replacement.

The rebleeding rates in the CE results are summarized in Table 2. Of the 95 patients, 27 (28.4%) showed one or more rebleeding events during follow-up. The median time to rebleeding was 10.0 mo (range 1.0-25.0 mo). The rebleeding rate in patients with positive and negative CE was 36.8% and 22.8%, respectively. There was no significant difference in rebleeding between these two groups (P = 0.205, log rank test; Figure 1). In addition, there was no significant difference in the cumulative rebleeding rates between P1 and P0 lesion groups (P = 0.711, log rank test). Subsequent hospitalization for bleeding was required in five patients (13.2%) in the CE-positive group compared to seven (12.3%) in the CE-negative group (P = 1.000). Subsequent blood transfusions were given in three (7.9%) vs six (10.5%) patients, respectively (P = 1.000).

On the basis of multivariable analysis via the Cox proportional hazards analysis, anticoagulation therapy was independently associated with an increased risk of rebleeding [hazard ratio (HR), 5.019; 95%CI, 1.560-16.145; P = 0.007]. However, negative CE and specific treatment were not associated with a decreased risk of rebleeding (Table 3). To identify the risk factors for rebleeding in patients with negative CE, we performed subgroup analysis. Anticoagulation therapy was identified as an independent risk factor for rebleeding in patients with negative CE (HR, 7.069; 95% CI: 1.942-29.809; P = 0.004).

| Variables | Hazard ratio | 95%CI | P value |

| Male | 2.082 | 0.882-4.910 | 0.094 |

| Age > 50 yr | 0.980 | 0.328-2.922 | 0.971 |

| Hb < 8 g/dL | 0.861 | 0.365-2.029 | 0.732 |

| Transfusion before CE | 1.719 | 0.674-4.382 | 0.257 |

| Comorbidity | 1.619 | 0.661-3.969 | 0.292 |

| Aspirin use | 1.020 | 0.357-2.914 | 0.970 |

| Anticoagulation use | 5.019 | 1.560-16.145 | 0.007 |

| NSAIDs use | 1.153 | 0.314-4.232 | 0.830 |

| Obscure-overt bleeding | 1.143 | 0.382-3.416 | 0.811 |

| Specific treatment | 1.123 | 0.368-3.422 | 0.839 |

| Positive CE | 1.564 | 0.561-4.355 | 0.392 |

CE is a safe and effective tool in evaluating small-bowel disease. It is generally accepted as the first diagnostic choice for patients with OGIB[3]. It provides a higher diagnostic yield compared to other modalities because of its improved visualization. However, there are several limitations of CE reported in evaluations of small-bowel pathology. These include a limited visual field of the bowel lumen, poor bowel preparation, inadequate luminal distension, rapid passage around the proximal small bowel, and incomplete study of the cecum[16,17]. Therefore, it is plausible that CE can miss significant lesions; a risk which could translate into poor prognosis in patients with OGIB in the long term. Although there have been many reports determining the clinical impact of negative CE, the long-term risk of recurrent bleeding in patients with OGIB after negative CE remains controversial. According to a prospective analysis comparing CE with intraoperative endoscopy as the standard of reference, the negative predictive value (NPV) for CE was 86%[18]. Delvaux et al[19], in a 12-mo follow-up study, reported that the NPV was 100% in patients with normal findings on CE. In addition, several studies have reported that patients with OGIB and negative CE results have very low rebleeding rates[9,10,20,21]. Therefore, it has been generally accepted that a negative CE result predicts a favorable prognosis in patients with OGIB. However, a well-designed prospective study reported that the rebleeding rate during 1-year follow-up was 33% in patients with normal CE findings[22]. Moreover, a retrospective study demonstrated that there was no significant difference in the cumulative rebleeding rates between patients with positive CE and those with negative CE[11]. The present study demonstrated that the overall rebleeding rates in patients with positive and negative CE results during the minimum 6 mo follow-up period were 36.8% and 22.8%, respectively. There was no significant difference in the cumulative rebleeding rates between these two groups. In addition, multivariate analysis showed that CE results were not associated with a risk of rebleeding. Therefore, our results indicate that the risk for recurrent bleeding is considerable, even if patients with OGIB have negative CE results.

According to the current recommendations for OGIB from the American Gastroenterological Association, subsequent intervention directed by CE findings is recommended in patients with positive CE results. Moreover, further diagnostic testing can be deferred in patients with negative CE, and balloon-assisted endoscopy is considered only in patients with a high suspicion of small-bowel pathology. However, little information is available on the duration of follow-up. The duration of follow-up in previous studies, which found very low rebleeding rates, was only 12 mo[19,21]. However, increased rebleeding rates have been reported with longer follow-up periods in recent studies[9,10]. In the present study, approximately 50% of the patients showed a first rebleeding episode > 1 year after the initial bleeding, while the maximum time to rebleeding was 24 mo after a negative CE result. Moreover, Park et al[11] reported a rebleeding rate of 35.7% during 32 mo follow-up. On the basis of these results, a close follow-up duration of at least 2 years is needed in patients with OGIB, even if patients have negative CE findings (Table 4).

CE can improve the diagnostic yield in patients with OGIB, but it remains uncertain whether CE improves clinical outcomes. A recent, prospective, randomized control trial demonstrated that a substantial improvement in diagnostic yield with the use of CE did not lead to improved outcome in patients with OGIB[22]. In addition, a recent study showed that positive CE results are not predictive of a favorable outcome in patients with iron-deficiency anemia[23]. On that basis, treatment directed by CE may not improve long-term outcome in patients with OGIB. In contrast, Park et al[11] demonstrated that specific treatments decrease long-term rebleeding after CE, suggesting that vigorous investigation to detect the bleeding focus could definitely reduce the rebleeding. In addition to this, Delvaux et al[19] also showed that only one among 18 patients who were treated directed by CE relapsed during 1 year follow-up. In the present study, a significant proportion (63.2%) of patients with positive CE results had specific treatment. Higher rebleeding rate was found in patients with angiodysplasia and IBD, while patients with tumors exhibited no rebleeding after surgical intervention. There was no significant difference in the cumulative rebleeding rates regardless of specific treatment. In addition, multivariate analysis showed that specific treatment did not reduce the risk of rebleeding. These results suggest that CE plays a limited role in clinical outcome among patients with OGIB. However, these results should be interpreted with caution because our data were retrospectively obtained from a single tertiary referral hospital. Outcomes in patients with OGIB are likely attributable to various etiologies and to the severity of initial presentation. Moreover, the natural history of etiology such as angiodysplasia remains unclear. Therefore, prospective, well-designed, long-term follow-up studies that include the various etiologies of OGIB are required to determine whether diagnostic testing with CE will translate into a significant improvement in the management and outcome in patients with OGIB.

There are no clear guidelines for evaluating patients with initially negative CE results. The management of these patients with OGIB remains elusive. However, patients with evidence of ongoing or recurrent OGIB need further investigation. The options include repeat upper and lower endoscopy, CE, DBE, radiology or nuclear medicine, and intraoperative enteroscopy[24]. In a recent study, patients with initial negative CE results benefited from a second-look CE if the bleeding presentation changed from occult to overt, or if hemoglobin decreased by ≥ 4 g/dL[25]. In addition to this, DBE could be useful in evaluating patients with negative CE results because it has a diagnostic yield similar to that of CE[26]. Furthermore, it has great advantages in providing histological confirmation and simultaneous treatment[27]. Therefore, well-designed prospective studies are required to improve the management in OGIB patients with a nondiagnostic CE test.

Our study had a few limitations. First, the data were obtained from a single tertiary referral hospital and the study was of retrospective design. Second, balloon-assisted endoscopy was not performed in most of the patients. Therefore, the possibility exists that a less-invasive approach might have led to higher rebleeding rates in both groups. Finally, it is possible that some lesions may have been missed because our data included incomplete CE results.

In conclusion, patients with OGIB and negative CE have a potential risk of rebleeding. Therefore, close observation is needed even in patients with negative CE and alternative modalities should be considered in clinically suspicious cases.

Presented as a poster at DDW (Digestive Disease Week), May 7-10, 2011, Chicago, IL.

Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) represent about 5% of all gastrointestinal hemorrhage and is defined as recurrent or persistent bleeding or iron-deficiency anemia originating from the gastrointestinal tract, with negative results from upper and lower endoscopy. Capsule endoscopy (CE) is useful for detection of the cause of small-bowel hemorrhage, and has a higher diagnostic yield than other diagnostic modalities.

Wireless CE is considered a first-line investigation in patients with OGIB. However, a significant proportion of patients with OGIB have nondiagnostic CE results. Although many studies have investigated the diagnostic yield of CE, little information is available about long-term outcome in patients after negative CE. In addition, it remains uncertain whether treatment directed by CE improves long-term outcome in patients with OGIB.

This study showed that the rebleeding rate in patients with OGIB after negative CE results was substantial. Treatment directed by CE did not reduce the risk of rebleeding.

The study showed that negative CE did not predict a favorable outcome, which suggests that close observation for rebleeding is warranted.

The authors have reported that patients with OGIB and negative CE have a potential risk of rebleeding. Treatments directed by CE were not associated with a decreased risk of rebleeding. The data provided in this study contribute to understanding the long-term outcome in patients with OGIB.

| 1. | Carey EJ, Leighton JA, Heigh RI, Shiff AD, Sharma VK, Post JK, Fleischer DE. A single-center experience of 260 consecutive patients undergoing capsule endoscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:89-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rockey DC. Occult gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:38-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Raju GS, Gerson L, Das A, Lewis B. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute technical review on obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1697-1717. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Marmo R, Rotondano G, Piscopo R, Bianco MA, Cipolletta L. Meta-analysis: capsule enteroscopy vs. conventional modalities in diagnosis of small bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:595-604. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Mazzarolo S, Brady P. Small bowel capsule endoscopy: a systematic review. South Med J. 2007;100:274-280. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Lewis BS, Eisen GM, Friedman S. A pooled analysis to evaluate results of capsule endoscopy trials. Endoscopy. 2005;37:960-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Koulaouzidis A, Rondonotti E, Giannakou A, Plevris JN. Diagnostic yield of small-bowel capsule endoscopy in patients with iron-deficiency anemia: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:983-992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Hadithi M, Heine GD, Jacobs MA, van Bodegraven AA, Mulder CJ. A prospective study comparing video capsule endoscopy with double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:52-57. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Lai LH, Wong GL, Chow DK, Lau JY, Sung JJ, Leung WK. Long-term follow-up of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after negative capsule endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1224-1228. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Macdonald J, Porter V, McNamara D. Negative capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure GI bleeding predicts low rebleeding rates. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:1122-1127. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Park JJ, Cheon JH, Kim HM, Park HS, Moon CM, Lee JH, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim WH. Negative capsule endoscopy without subsequent enteroscopy does not predict lower long-term rebleeding rates in patients with obscure GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:990-997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Postgate A, Despott E, Burling D, Gupta A, Phillips R, O’Beirne J, Patch D, Fraser C. Significant small-bowel lesions detected by alternative diagnostic modalities after negative capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:1209-1214. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Chong AK, Chin BW, Meredith CG. Clinically significant small-bowel pathology identified by double-balloon enteroscopy but missed by capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:445-449. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Saurin JC, Delvaux M, Gaudin JL, Fassler I, Villarejo J, Vahedi K, Bitoun A, Canard JM, Souquet JC, Ponchon T. Diagnostic value of endoscopic capsule in patients with obscure digestive bleeding: blinded comparison with video push-enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2003;35:576-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gralnek IM, Defranchis R, Seidman E, Leighton JA, Legnani P, Lewis BS. Development of a capsule endoscopy scoring index for small bowel mucosal inflammatory change. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:146-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 284] [Cited by in RCA: 332] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rondonotti E, Herrerias JM, Pennazio M, Caunedo A, Mascarenhas-Saraiva M, de Franchis R. Complications, limitations, and failures of capsule endoscopy: a review of 733 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:712-76; quiz 752, 754. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Westerhof J, Weersma RK, Koornstra JJ. Risk factors for incomplete small-bowel capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:74-80. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Hartmann D, Schmidt H, Bolz G, Schilling D, Kinzel F, Eickhoff A, Huschner W, Möller K, Jakobs R, Reitzig P. A prospective two-center study comparing wireless capsule endoscopy with intraoperative enteroscopy in patients with obscure GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:826-832. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Delvaux M, Fassler I, Gay G. Clinical usefulness of the endoscopic video capsule as the initial intestinal investigation in patients with obscure digestive bleeding: validation of a diagnostic strategy based on the patient outcome after 12 months. Endoscopy. 2004;36:1067-1073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Iwamoto J, Mizokami Y, Shimokobe K, Yara S, Murakami M, Kido K, Ito M, Hirayama T, Saito Y, Honda A. The clinical outcome of capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:301-305. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Lorenceau-Savale C, Ben-Soussan E, Ramirez S, Antonietti M, Lerebours E, Ducrotté P. Outcome of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after negative capsule endoscopy: results of a one-year follow-up study. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010;34:606-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Laine L, Sahota A, Shah A. Does capsule endoscopy improve outcomes in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding? Randomized trial versus dedicated small bowel radiography. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1673-1680.e1; quiz e11-2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Holleran GE, Barry SA, Thornton OJ, Dobson MJ, McNamara DA. The use of small bowel capsule endoscopy in iron deficiency anaemia: low impact on outcome in the medium term despite high diagnostic yield. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:327-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Liu K, Kaffes AJ. Review article: the diagnosis and investigation of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:416-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Viazis N, Papaxoinis K, Vlachogiannakos J, Efthymiou A, Theodoropoulos I, Karamanolis DG. Is there a role for second-look capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure GI bleeding after a nondiagnostic first test? Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:850-856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Fukumoto A, Tanaka S, Shishido T, Takemura Y, Oka S, Chayama K. Comparison of detectability of small-bowel lesions between capsule endoscopy and double-balloon endoscopy for patients with suspected small-bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:857-865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kita H, Yamamoto H. Double-balloon endoscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of small intestinal disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:179-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewers Figueiredo P, Velayos B S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L