Published online Jan 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i1.108

Revised: November 14, 2012

Accepted: November 24, 2012

Published online: January 7, 2013

AIM: To compare the outcomes between double-guidewire technique (DGT) and transpancreatic precut sphincterotomy (TPS) in patients with difficult biliary cannulation.

METHODS: This was a prospective, randomized study conducted in single tertiary referral hospital in Korea. Between January 2005 and September 2010. A total of 71 patients, who bile duct cannulation was not possible and selective pancreatic duct cannulation was achieved, were randomized into DGT (n = 34) and TPS (n = 37) groups. DGT or TPS was done for selective biliary cannulation. We measured the technical success rates of biliary cannulation, median cannulation time, and procedure related complications.

RESULTS: The distribution of patients after randomization was balanced, and both groups were comparable in baseline characteristics, except the higher percentage of endoscopic nasobiliary drainage in the DGT group (55.9% vs 13.5%, P < 0.001). Successful cannulation rate and mean cannulation times in DGT and TPS groups were 91.2% vs 91.9% and 14.1 ± 13.2 min vs 15.4 ± 17.9 min, P = 0.732, respectively. There was no significant difference between the two groups. The overall incidence of post- endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis was 38.2% vs 10.8%, P < 0.011 in the DGT group and the TPS group; post-procedure pancreatitis was significantly higher in the DGT group. But the overall incidence of post-ERCP hyperamylasemia was no significant difference between the two groups; DGT group vs TPS group: 14.7% vs 16.2%, P < 1.0.

CONCLUSION: When free bile duct cannulation was difficult and selective pancreatic duct cannulation was achieved, DGT and TPS facilitated biliary cannulation and showed similar success rates. However, post-procedure pancreatitis was significantly higher in the DGT group.

-

Citation: Yoo YW, Cha SW, Lee WC, Kim SH, Kim A, Cho YD. Double guidewire technique

vs transpancreatic precut sphincterotomy in difficult biliary cannulation. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(1): 108-114 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i1/108.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i1.108

Selective biliary cannulation is an important step for therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). In the hands of experienced endoscopists, successful biliary cannulation rates are higher than 90%[1]. However, in some cases, bile duct (BD) cannulation can be difficult because of special anatomical features, inflammatory processes, and adenomas of the papilla or periampullary diverticulum. Large prospective studies have demonstrated that difficult cannulation is an independent risk factor for post-ERCP pancreatitis[2-4]. In the past few years, various efforts have been made to develop alternative endoscopic techniques, with the goal of increasing the rate of successful biliary cannulation. The use of a guidewire to physically occupy the pancreatic duct (PD), also known as the double-guidewire technique (DGT), was initially described by Dumonceau et al[5]. Since its first description, this method has been used with promising results in cases of complex biliary cannulation, especially in patients with a distorted BD anatomy caused by neoplasia or atypical morphology of the ampulla[6].

Transpancreatic precut sphincterotomy (TPS) using a guidewire, another technique for difficult biliary cannulation, was first described by Goff[7] in 1995. A sphincterotomy over the guidewire in the PD helps to cannulate the biliary orifice because the cut either opens the BD or runs along the side of the duct, thus exposing the duct’s anatomy.

DGT and TPS might facilitate biliary cannulation. However, post-ERCP pancreatitis has been reported to occur with DGT and TPS in 0% to 25% of patients[6,8-11]. Most previous studies compared the performance of the new techniques with standard cannulation techniques or precut sphincterotomy. However, there has been no prospective, randomized study of the performance of DGT with TPS in patients with difficult biliary cannulation. Therefore, we designed this randomized, prospective study to compare the outcomes of DGT and TPS in patients with difficult biliary cannulation.

This was a prospective, randomized study conducted in the Tertiary Referral Hospital in South Korea. Between January 2005 and September 2010, a total of 1893 ERCPs were performed at Eulji University Hospital, and 71 patients were enrolled in this study. Consecutive patients were considered for inclusion if they underwent ERCP with clear indication of biliary access. Among these patients, those in whom free cannulation of the BD was not possible and selective PD cannulation was achieved without difficulty were enrolled in this study. Patients were excluded for any of the following reasons: (1) age of less than 18 years; (2) subjects who underwent prior biliary or pancreatic sphincterotomy or dilatation or stenting of either duct; (3) acute pancreatitis at the time of the procedure; and (4) intrauterine pregnancy.

Enrolled patients were randomly assigned to either the DGT group or the TPS group. A randomization list for group allocation was generated using computer-based pseudo-random number generators. We compared both techniques for a maximum of 10 extra attempts after randomization which are common BD (CBD) cannulation by each method. Thus, we did not impose a time limit for CBD cannulation. We received approval by our hospital’s institutional review board and obtained written informed consent from all 1394 patients.

Benzodiazepines, anti-spasmodic agents, and non-narcotic analgesics, alone or in combination, were administered routinely before the procedure. Therapy with antibiotics and analgesics was allowed to continue. One senior endoscopist directly performed all procedures using side-viewing endoscopes (JF-240, JF-260V, and TJF-240; Olympus Optical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

Standard cannulation techniques were used to attempt biliary cannulation. However, if BD cannulation failed with standard techniques but the PD was successfully cannulated, patients were randomly assigned to either the DGT group or the TPS group, and selective BD cannulation was continued with those techniques.

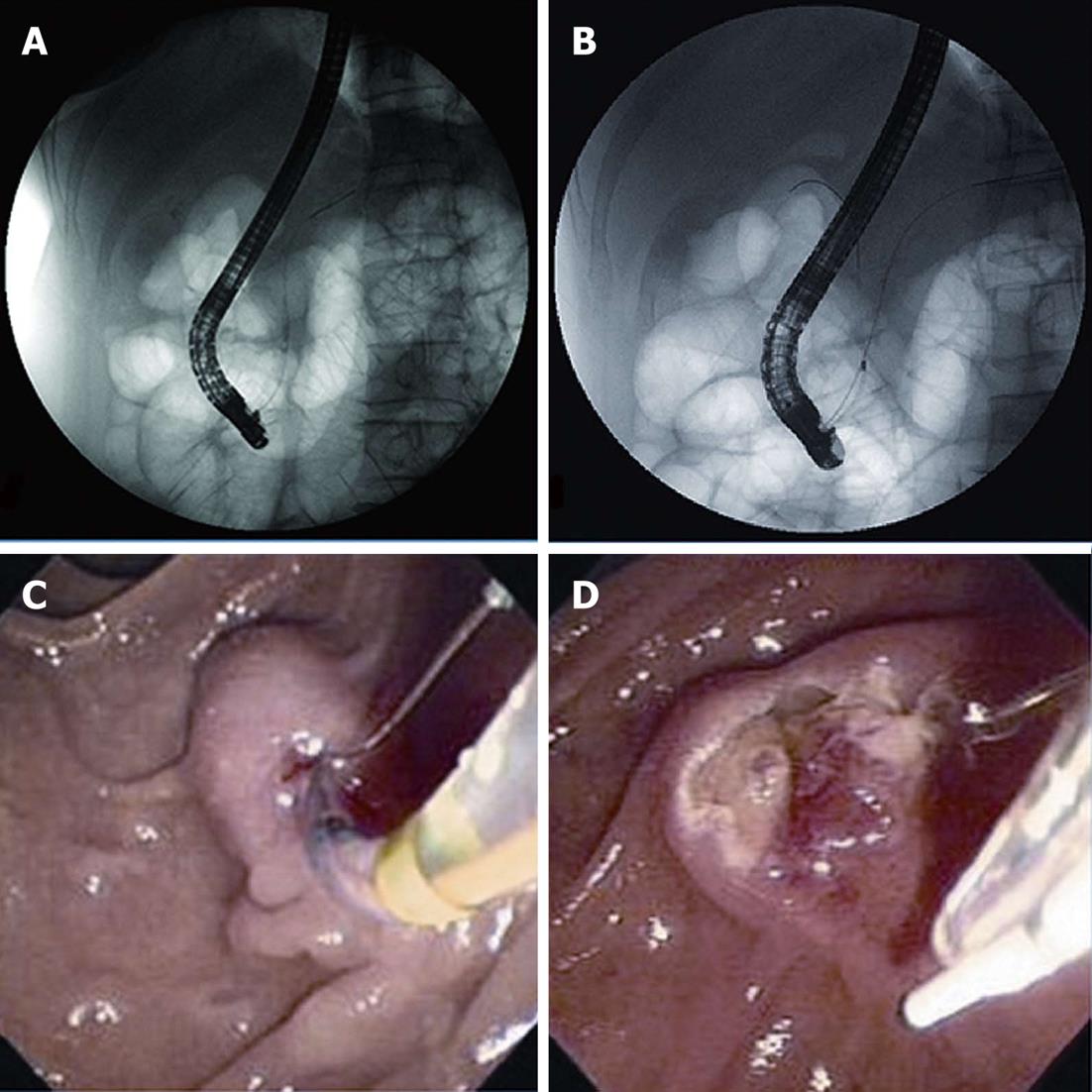

The DGT was performed as follows. First, after PD cannulation had been achieved without difficulty, a guidewire (0.035-inch Tracer Hybrid® Wire Guide; Wilson-Cook Medical, Bloomington, United States) was left in the PD. Second, another cannula or sphincterotome was passed into the same working channel of the scope alongside the guidewire using the two-devices-in-one-channel method. The tip of the device was positioned in the papilla, and another guidewire (0.035-inch Tracer Metro® Direct™ Wire Guide; Wilson-Cook Medical, Bloomington, United States) was bent over the pancreatic wire to attempt cannulation of the BD (Figure 1A and B).

TPS was performed as follows. After a guidewire (0.035-inch Tracer Hybrid® Wire Guide; Wilson-Cook Medical, Bloomington, United States) had been inserted deeply into the PD without difficulty, the tip of a standard traction sphincterotome was wedged into the pancreatic orifice, and a sphincterotomy was performed with a cutting wire along the biliary direction at 11 o’clock. The incision was made through the septum between the pancreatic and biliary duct with the aim of exposing the BD orifice. The BD orifice was exposed to the left and either below or above the pancreatic orifice. After TPS, the guidewire placed in the PD was removed. Biliary cannulation was then attempted using a catheter or sphincterotome, either with or without a guidewire at the discretion of the endoscopist (Figure 1C and D).

When cannulation of the BD was achieved with the DGT or TPS procedure, additional procedures were performed as necessary.

Serum amylase and lipase levels were checked before ERCP, 4 h and 24 h after ERCP, and when clinically indicated. The presence of abdominal pain attributable to the pancreas and the use and type of analgesic therapy were evaluated at those times.

The primary outcome measure was the successful biliary cannulation rate. Secondary outcome measures were the median cannulation time and the rates of post-procedure-related complications, post-ERCP pancreatitis, bleeding, perforation, cholangitis, and cholecystitis.

The standard cannulation technique was defined as the use of a cannulation device (catheter or sphincterotome) preloaded with a guidewire, positioned in the ampullary orifice, and targeting the presumed entry of the CBD. Each cannulation attempt started when the device was inserted into the ampullary orifice and ended when the device was disengaged from the papilla; during the same attempt, while the cannulation device was still in contact with the papilla.

Cannulation success was determined as the achievement of deep biliary cannulation. Difficult biliary cannulation was defined as unsuccessful cannulation after 10 or more attempts with a cannula/sphincterotome or failure of cannulation after 10 min. Successful biliary cannulation at the time of DGT or TPS was considered to be an initial success. In cases in which the first biliary cannulation failed after DGT or TPS, ERCP was repeated within 2 d to 5 d with the consent of the patient, and the same cannulation technique was performed during the second ERCP attempt. Successful biliary cannulation on the first or second ERCP attempt was considered the final success.

The definition of post-ERCP pancreatitis was based on consensus criteria[12], as follows: newly developed or increased abdominal pain within 24 h after ERCP requiring analgesic agents, and the elevation of the serum amylase and/or lipase level by at least three times the normal upper limit at about 24 h after the procedure. Hyperamylasemia was defined as elevation of serum amylase levels to more than three times the normal upper limit at 4 and/or 24 h after the ERCP, without other symptoms. The severity of pancreatitis, bleeding, cholangitis, and perforation were defined as described elsewhere[12].

Our hypothesis was that the success rates of biliary cannulation were similar using either DGT or TPS; however, the post-ERCP pancreatitis rate may be lower in the TPS group than in the DGT group. Because an unrealistically large sample size would have been required to examine the biliary cannulation rates in the setting of an equivalence trial, the comparison of post-ERCP pancreatitis rates in a superiority setting was the basis for sample size calculation. Thirty-one patients in each group were needed to detect such a difference with a two-tailed χ2 test, an a value of 0.05, and a statistical power of 80%.

The data were analyzed with SPSS version 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Continuous variables were described as median (interquartile range) and compared using Student’s t-test. Categorical variables were tested using an χ2 test. Statistical significance was indicated by a two-tailed P value of < 0.05. It is recognized that there was multiple testing of outcome data arising from individual patients. In that regard, there was no correction made to the P value for the comparison of post-ERCP pancreatitis rates because that comparison was considered to be the focal point when making sample size calculations. All other statistical tests of outcome results should be considered to be secondary, and their results should be taken as descriptive only.

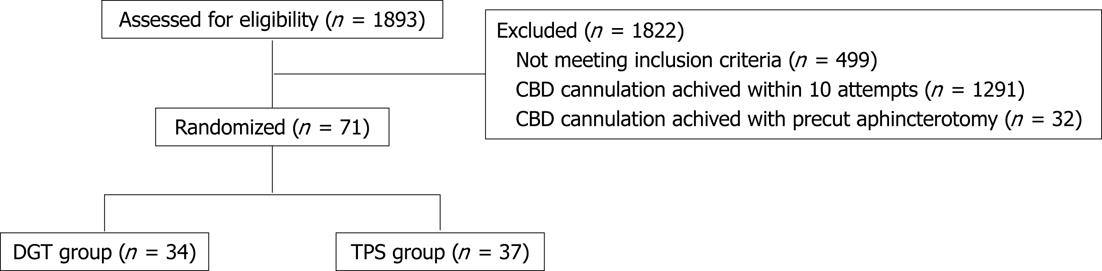

During the study period, 1893 ERCPs were performed at Eulji University Hospital. We excluded 499 patients for the following reasons: age of < 18 years (five patients); previous endoscopic sphincterotomy or endoscopic papillary balloon dilation (399 patients); acute pancreatitis before ERCP (222 patients); and pregnancy (three patients). After this exclusion, ERCP was attempted in the remaining 1394 patients with the native papilla of Vater with standard cannulation technique. In 1291 patients (92.6%), selective BD cannulation was achieved within 10 attempts and 10 min; difficult biliary cannulation occurred in 103 (7.4%) patients. Of these, PD cannulation was also not achieved in 32 patients. Finally, 71 patients in whom deep PD guidewire cannulation was achieved were enrolled in this study and randomly assigned to the DGT group (34 patients) or the TPS group (37 patients) (Figure 2).

The distribution of patients after randomization was balanced, and both groups were comparable in terms of their baseline characteristics, such as ERCP indication, devices used, ERCP findings, and maneuvers. The only significant difference was a higher percentage of endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) in the DGT group (55.9% vs 13.5%, P < 0.001) (Table 1).

| DGT groupn = 34 (%) | TPS groupn = 37 (%) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 67.0 (11.5) | 63.7 (16.5) | 0.326 |

| Sex | 0.478 | ||

| Male | 18 (52.9) | 23 (62.2) | |

| Female | 16 (47.1) | 14 (37.8) | |

| Indication of ERCP | 0.222 | ||

| CBD stone | 14 (41.2) | 16 (43.2) | |

| GB stone | 7 (20.6) | 6 (16.2) | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 8 (23.5) | 6 (16.2) | |

| Pancreatic cancer | 1 (2.9) | 3 (8.1) | |

| Other bile duct disease | 3 (8.8) | 2 (5.4) | |

| Other pancreatic disease | 1 (2.9) | 4 (10.8) | |

| PADD | 9 (26.5) | 5 (13.5) | 0.426 |

| Type I | 2 (5.9) | 0 (0) | |

| Type II | 5 (14.7) | 4 (10.8) | |

| Type III | 2 (5.9) | 1 (2.7) | |

| ERCP maneuver | |||

| Contrast injection in PD | 34 (100) | 33 (89.2) | 0.116 |

| EST | 25 (73.5) | 28 (75.7) | 0.629 |

| CBD stone extraction | 13 (38.2) | 12 (32.4) | 0.823 |

| EPBD | 3 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 0.153 |

| ENBD | 19 (55.9) | 5 (13.5) | < 0.001 |

| ERBD | 3 (8.8) | 5 (13.5) | 0.574 |

| Successful cannulation | |||

| First trial | 27 (79.4) | 29 (78.4) | 0.915 |

| Including second trial | 31 (91.2) | 34 (91.9) | 0.914 |

| Failure of cannulation | 3 (8.8) | 3 (8.1) | 0.914 |

| Median cannulation time, min (IQR) | 19.0 (11.0-37.0) | 20.5 (12.8-34.75) | 0.732 |

| Post-ERCP hyperamylasemia | 5 (14.7) | 6 (16.2) | 1.000 |

| Post-ERCP pancreatitis | 13 (38.2) | 4 (10.8) | 0.011 |

| Mild PEP | 10 (29.4) | 3 (8.1) | 0.031 |

| Moderate to severe PEP | 3 (8.8) | 1 (2.7) | 0.344 |

| Bleeding | 1 (2.9) | 2 (5.4) | 1.000 |

| Cholangitis | 7 (20.6) | 2 (5.4) | 0.077 |

| Cholecystitis | 0 | 0 | - |

| Perforation | 0 | 0 | - |

Within the limit of 10 extra attempts, initial successful biliary cannulation was achieved in 27 of the 34 (79.4%) patients in the DGT group and 29 of the 37 (78.4%) patients in the TPS group. Additional successful biliary cannulation was achieved in four and five patients using the initial technique in the second ERCP trial. Thus, the overall successful biliary cannulation rates, including the repeat ERCPs, were 91.2% (31/34) in the DGT group and 91.9% (34/37) in the TPS group. There was no significant difference in the initial and final cannulation rates of BD between the two groups (Table 1).

In patients who underwent successful biliary cannulation, the mean time of cannulation was 14.1 min in the DGT group and 15.4 min in the TPS group; the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (Table 1).

The overall incidence of post-ERCP hyperamylasemia was 14.7% (5/34) in the DGT group and 16.2% (6/37) in the TPS group. There was no significant difference between the two groups. Post-ERCP pancreatitis developed in 38.2% (13/34) of the DGT group and 10.8% (4/37) of the TPS group. Post-ERCP pancreatitis was significantly higher in the DGT group than in the TPS group (P = 0.011). However, most cases of pancreatitis were mild. Moderate or severe pancreatitis developed rarely in both groups (Table 1).

One episode of bleeding occurred in the DGT group (2.9%), and two were detected in the TPS group (5.4%). Acute cholangitis developed in 20.6% (7/34) of the DGT group and 5.4% (2/37) of the TPS group. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups in the rates of procedure-related bleeding or cholangitis. However, the incidence of cholangitis in the DGT group was higher than that in the TPS group. Acute cholecystitis and perforation were not detected in any group (Table 1).

Several techniques of overcoming difficult biliary cannulation have evolved in the past few years. Needle-knife papillotomy is frequently used to open the biliary entrance and is highly successful when performed by an expert endoscopist. However, the disadvantage of this method is the higher rate of complications, including bleeding, perforation, and pancreatitis. Complication rates of 6% to more than 20% have been reported[2,12,13]. In the 1990s, new techniques for overcoming difficult biliary cannulation, such as DGT, TPS, and wire-guided biliary cannulation over the PD stent, were introduced.

The superior rate of biliary cannulation when using DGT has been attributed to the capability of the pancreatic guidewire to straighten both the PD and BD while at the same time occupying the PD, thus facilitating biliary cannulation and preventing repeated pancreatic cannulation[14,15]. One prospective randomized study reported by Maeda et al[8] compared DGT with standard methods, and indicated a higher cannulation success rate (93%) with DGT with no apparent added risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis. However, in the most recent prospective randomized multicenter study by Herreros de Tejada et al[6], DGT was not superior to standard cannulation techniques (success rates of 47% and 56%, respectively) and may have been associated with a higher risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis (17% and 8%, respectively).

TPS can facilitate cannulation of the biliary orifice because the cut either opens the BD or runs along the side of the duct, thus exposing the orifice. Akashi et al[16] published a prospective series in which TPS was successful in approximately 60% of the patients immediately and in 95% with repeated ERCP. However, the complication rates of TPS were significantly higher than those of standard biliary sphincterotomy (9.9% vs 0.8%, P < 0.001). In another prospective study by Kahaleh et al[17], the primary success rate of pancreatic sphincterotomy was 85%, which, when combined with the needle-knife technique, rose to 95%. The rate of post-ERCP pancreatitis was 8%, which was not different from that of conventional biliary sphincterotomy.

Our results show that the two techniques facilitate selective biliary cannulation with a similar success rate. The initial success rate of DGT in our study was 79.4%, and the final success rate, including the repeat ERCP, was 91.2%. This result is similar to that reported by Maeda et al[8] (92.6%), but higher than that reported by Herreros de Tejada et al[6] (47%). In the latter study, the difficult cannulation rates were as high as 49.5% and 22%. In comparison, the difficult biliary cannulation rate in our study was lower and more comparable with the experience in high-volume centers. Our difficult biliary cannulation rate was only 7.4%, which represented a truly difficult biliary cannulation group.

In our study, the initial success rate of TPS was 78.4%, and the final success rate was 91.9%. These results are similar to those reported elsewhere[16,17].

The incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis after DGT was significantly higher than that after TPS (38.2% vs 10.8%, P = 0.011). Four patients in the DGT group needed special attention. Their total ERCP procedure time was more than 45 min. There were almost twice as many patients with periampullary duodenal diverticulum in the DGT group, but this difference was not statistically significant. Those patients needed more extensive manipulation; therefore, the longer procedure time and the more extensive manipulation might have had an effect on the development of post-ERCP pancreatitis. This may have been another reason for the higher pancreatitis rate in the DGT group. We kept the guidewire inserted into the PD for a longer period of time while attempting selective BD cannulation and removed the PD guidewire after BD cannulation. Conversely, TPS allowed for drainage of the pancreatic juice spontaneously via the PD opening, which may have helped decrease the rate of pancreatitis.

The overall post-ERCP pancreatitis rate in this study was 23.9% (17/71). This is similar to those of previous studies, and most cases of pancreatitis were mild. However, in contrast to the other studies, we did not perform prophylactic PD stenting in any of the cases. The PD stent facilitates biliary cannulation and prevents post-ERCP pancreatitis, but is not usually used in Korea because the health insurance system does not cover the costs of PD stents for prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis and the financial burden of patients is substantially increased by their use. Another difference is that we did not use any pharmacologic agents for post-ERCP pancreatitis, such as protease inhibitors, which are widely used by Japanese endoscopists. This might have lowered the frequency of post-ERCP pancreatitis in previous studies.

Problems with using a pancreatic guidewire include the potential for injuring branch ducts and the failure to place the guidewire deeply enough into a tortuous main duct. In our study, guidewire insertion into the PD was performed under the guidance of contrast and fluoroscopy to minimize branch duct injury. However, repeated PD injection of contrast is one of the risk factors of post-ERCP pancreatitis.

The incidence of cholangitis after DGT was almost four times higher than that after TPS (20.6% vs 5.4%, P = 0.077); however, this difference was not statistically significant. Patients with cholangitis had CBD stones or CBD stricture and underwent ENBD insertion. Therefore, we believe that the difference in cholangitis incidence was due to a difference not in methods, but in patients’ characteristics. We believe that this is due to post hoc fallacy.

Our study has some limitations. First, the number of enrolled patients was relatively small, and the study was conducted in a single tertiary center. We enrolled only 71 patients with difficult cannulation from among a total of 1394 patients (5.1%) who presented for ERCP during the study period. This may have influenced the interpretation of the difference in success and post-ERCP pancreatitis rates. Therefore, a larger study is necessary to overcome this limitation. Second, information regarding the number of PD injections and patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction were not collected. This is one of the main limiting factors in drawing a firm conclusion regarding the role of guidewire insertion in the PD in post-ERCP pancreatitis.

In conclusion, we report here successful PD cannulation in cases of difficult BD cannulation. Both the DGT and TPS facilitated biliary cannulation and showed similar success rates. However, the incidence of post-procedure pancreatitis was significantly higher in the DGT group. Therefore, we suggest that the use of TPS when the standard biliary cannulation technique fails and PD cannulation is achieved is effective and has an acceptable complication profile. Further large-scale multicenter studies are needed.

Selective biliary cannulation is an important step for therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). In the hands of experienced endoscopists, successful biliary cannulation rates are higher than 90%. However, in some cases, bile duct (BD) cannulation can be difficult because of special anatomical features, inflammatory processes, and adenomas of the papilla or periampullary diverticulum.

Double-guidewire technique (DGT) and transpancreatic precut sphincterotomy (TPS) might facilitate biliary cannulation. Most previous studies compared the performance of the new techniques with standard cannulation techniques or precut sphincterotomy. However, there has been no prospective, randomized study of the performance of DGT with TPS in patients with difficult biliary cannulation.

Authors designed this randomized, prospective study to compare the outcomes of DGT and TPS in patients with difficult biliary cannulation. They measured the technical success rates of biliary cannulation, median cannulation time, and procedure related complications.

Several techniques of overcoming difficult biliary cannulation have evolved in the past few years. Needle-knife papillotomy is frequently used to open the biliary entrance and is highly successful when performed by an expert endoscopist. The superior rate of biliary cannulation when using DGT has been attributed to the capability of the pancreatic guidewire to straighten both the pancreatic duct and BD. TPS can facilitate cannulation of the biliary orifice because the cut either opens the BD or runs along the side of the duct, thus exposing the orifice.

Excellent prospective randomized study designed to compare the outcome between two different techniques for endoscopic biliary cannulation. Because this is a randomised controlled trial which showed differences in post ERCP pancreatitis between the 2 methods, it can be published.

| 1. | Ramirez FC, Dennert B, Sanowski RA. Success of repeat ERCP by the same endoscopist. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:58-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1703] [Article Influence: 56.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Vandervoort J, Soetikno RM, Tham TC, Wong RC, Ferrari AP, Montes H, Roston AD, Slivka A, Lichtenstein DR, Ruymann FW. Risk factors for complications after performance of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:652-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 4. | Masci E, Mariani A, Curioni S, Testoni PA. Risk factors for pancreatitis following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2003;35:830-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dumonceau JM, Devière J, Cremer M. A new method of achieving deep cannulation of the common bile duct during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Endoscopy. 1998;30:S80. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Herreros de Tejada A, Calleja JL, Díaz G, Pertejo V, Espinel J, Cacho G, Jiménez J, Millán I, García F, Abreu L. Double-guidewire technique for difficult bile duct cannulation: a multicenter randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:700-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Goff JS. Common bile duct pre-cut sphincterotomy: transpancreatic sphincter approach. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:502-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Maeda S, Hayashi H, Hosokawa O, Dohden K, Hattori M, Morita M, Kidani E, Ibe N, Tatsumi S. Prospective randomized pilot trial of selective biliary cannulation using pancreatic guide-wire placement. Endoscopy. 2003;35:721-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang P, Zhang W, Liu F, Li ZS, Ren X, Fan ZN, Zhang X, Lu NH, Sun WS, Shi RH. Success and complication rates of two precut techniques, transpancreatic sphincterotomy and needle-knife sphincterotomy for bile duct cannulation. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:697-704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Halttunen J, Keränen I, Udd M, Kylänpää L. Pancreatic sphincterotomy versus needle knife precut in difficult biliary cannulation. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:745-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Obana T, Horaguchi J, Takasawa O, Koshita S, Kanno Y, Ogawa T. Can pancreatic duct stenting prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis in patients who undergo pancreatic duct guidewire placement for achieving selective biliary cannulation? A prospective randomized controlled trial. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1183-1191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Freeman ML, Guda NM. ERCP cannulation: a review of reported techniques. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:112-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Freeman ML. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy: a review. Endoscopy. 1997;29:288-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Gyökeres T, Duhl J, Varsányi M, Schwab R, Burai M, Pap A. Double guide wire placement for endoscopic pancreaticobiliary procedures. Endoscopy. 2003;35:95-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gotoh Y, Tamada K, Tomiyama T, Wada S, Ohashi A, Satoh Y, Higashizawa T, Miyata T, Ido K, Sugano K. A new method for deep cannulation of the bile duct by straightening the pancreatic duct. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:820-822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Akashi R, Kiyozumi T, Jinnouchi K, Yoshida M, Adachi Y, Sagara K. Pancreatic sphincter precutting to gain selective access to the common bile duct: a series of 172 patients. Endoscopy. 2004;36:405-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kahaleh M, Tokar J, Mullick T, Bickston SJ, Yeaton P. Prospective evaluation of pancreatic sphincterotomy as a precut technique for biliary cannulation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:971-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewers Vege SS, Grande L S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L