Published online Feb 7, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i5.466

Revised: May 27, 2011

Accepted: June 3, 2011

Published online: February 7, 2012

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy of thalidomide in combination with other therapies to treat patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

METHODS: We performed a retrospective analysis of all patients with HCC who were treated with thalidomide for at least two months. The medical records of patients with HCC who were treated at our institution between April 2003 and March 2008 were reviewed. Image studies performed before and after treatment, tumor response, overall survival, and the decrease in α-fetoprotein (AFP) levels were evaluated.

RESULTS: A total of 53 patients with HCC received either 100 or 200 mg/d of thalidomide. The patient population consisted of 9 women and 44 men with a median age of 61 years. Thirty patients (56.6%) were classified as Child-Pugh A, and 12 patients (22.6%) were classified as Child-Pugh B. Twenty-six patients had portal vein thrombosis (49.1%), and 25 patients had extrahepatic metastasis (47.1%). The median duration of thalidomide treatment was 6.0 mo. Six of the 53 patients achieved a confirmed response (11.3%), one achieved a complete response (1.9%) and 5 achieved a partial response (9.4%). The disease control rate (CR + PR + SD) was 28.3% (95% CI: 17.8-42.4), and the median overall survival rate was 10.5 mo. The 1- and 2-year survival rates were 45% and 20%, respectively. Only one complete response patient showed an improved overall survival rate of 66.8 mo. Sixteen patients (30.2%) showed more than a 50% decrease in their serum AFP levels from baseline, indicating a better response rate (31.3%), disease control rate (43.8%), and overall survival time (20.7 mo). The therapy was well tolerated, and no significant toxicities were observed.

CONCLUSION: Thalidomide was found to be safe for advanced HCC patients, demonstrating anti-tumor activity including response, survival, and AFP decreases of greater than 50% from baseline.

- Citation: Chen YY, Yen HH, Chou KC, Wu SS. Thalidomide-based multidisciplinary treatment for patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A retrospective analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(5): 466-471

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i5/466.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i5.466

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most frequent primary liver cancer, the fifth most common malignancy worldwide (with over 700 000 new cases per year), and the third most common cause of cancer deaths[1]. In Taiwan, HCC, which ranks second among the major types of cancer in the list of cancer-related mortalities, is responsible for approximately 7000 to 8000 deaths per year[2]. Unfortunately, most patients seek treatment when the disease is beyond curative treatment (surgery or percutaneous ablation), and palliative care is the only alternative. According to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging classification[1] and treatment schedule, chemoembolization is the best option for intermediate-stage patients. However, for advanced-stage patients, no standard treatment was established until 2007. Systemic chemotherapy is generally ineffective and is associated with significant toxicity because hepatic function is often impaired by underlying cirrhosis that is often accompanied by hypersplenism and peripheral cytopenia[3]. Fortunately, after the positive results of the Study of Heart and Renal Protection (SHARP) trials[4], a new treatment, sorafenib, was approved for advanced-stage patients, which offers major improvements in overall survival and time to progression compared to placebo. There are many new modalities of treatment with more favorable therapeutic indices that are suitable for patients with advanced HCC. HCC is a hypervascular tumor that is one of the most antiangiogenic and angiogenesis-dependent tumors[5,6]. Consequently, it is reasonable to hypothesize that antiangiogenesis therapy may inhibit the growth of HCC. A number of antiangiogenic agents have been developed, including thalidomide, which is a glutamic acid derivative that was first described in 1953 when it was labeled as a sedative and anti-emetic agent. However, it was withdrawn from the European market 30 years ago because of its teratogenic effects[7]. Recently, oral thalidomide has been shown to inhibit basic fibroblast growth factor- and vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenesis of cancer cells[8,9]. Studies published on the efficacy of thalidomide in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma have reported modest responses to therapy with acceptable toxicity[10-12]. Treatment of patients with HCC continues to present a major challenge. We retrospectively analyzed our records of HCC patients who received thalidomide in combination with other therapies to determine whether thalidomide was effective.

Between April 2003 and March 2008, 53 patients with HCC were treated for at least two months with either 100 or 200 mg/d of thalidomide (50 mg/capsule, TTY Biopharm Co. Ltd., Taipei, Taiwan) at Changhua Christian Medical Center in Taiwan. HCC was diagnosed by histological examination and imaging findings. The diagnosis of HCC was confirmed by histological examination or the presence of all of the following criteria: (1) pathological diagnosis of HCC; (2) cirrhotic liver with a tumor size greater than 2 cm plus one dynamic image [computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resnane iamge (MRI)] or alpha fetoprotein (AFP) > 200 ng/mL; (3) cirrhotic liver with a tumor size of 1-2 cm plus two dynamic images (CT + MRI); and (4) non-cirrhotic liver greater than 2 cm plus one dynamic image (CT or MRI) and AFP > 200 ng/mL. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) advanced HCC (surgically unresectable); (2) failed previous local therapy, such as radiotherapy, hepatic arterial chemoembolization, radiofrequency ablation, or percutaneous interventional therapy; and (3) distant metastasis (lung, lymph node, or bone) that is not eligible for curative surgery and radiotherapy or locoregional therapy failure [e.g., transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), recurrence-free interval or percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI)]. All patients had bidimensionally measurable disease that was staged by the pathological tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) system, the Okuda system, and the BCLC parameters for HCC. The demographic data, details of the primary tumors, serum AFP levels, dates of recurrence, length of survival, and last follow-up dates were analyzed retrospectively. The responses to thalidomide were determined by CT performed according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumor Guidelines[13], and the AFP levels were also analyzed before and after thalidomide treatment. Overall survival was calculated from the date of the start of chemotherapy and analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method. Follow-up data were obtained for all patients until the time of their death or the last follow-up.

A total of 53 patients with HCC were available for analysis, and their demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. The patient population included 9 females (17.0%) and 44 males (83.0%) with a median age of 61 years (range, 29-88 years). Of the 53 patients, 10 had not received prior treatment or therapy. Pretreatment curative surgery had been performed on 12 patients (22.6%), transarterial embolization on 13 patients (24.5%), TACE on 16 patients (30.2%), radio frequency ablation on 10 patients (18.9%), and radiotherapy (RT) on 10 patients (18.9%). Twenty-six patients had portal vein thrombosis (49.1%), and 25 patients had extrahepatic metastasis (47.2%). The prevalence of hepatitis B was 56.5% (30/53), that of hepatitis C was 37.7% (20/53), and that of concomitant hepatitis was 1.9% (1/53). Of the 53 patients, most patients had TNM stage IV (45.3%), Okuda stageI(51.9%), and BCLC stage C (71.2%). There were 22 patients (41.5%) whose serum AFP levels were greater than 400 ng/mL above the baseline. The liver functions of the majority of patients were classified as Child-Pugh A (56.6%), and the median duration of treatment was 6.0 mo (range, 1.5-53.9 mo) (Table 1).

| Characteristic | n (%) |

| Age, yr (median) | 61 (range, 29-88) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 44 (83.0) |

| Female | 9 (17.0) |

| Type of hepatitis | |

| Hepatitis B | 30 (56.6) |

| Hepatitis C | 20 (37.7) |

| Hepatitis B + C | 1 (1.9) |

| Child-Pugh classification | |

| A | 30 (56.6) |

| B | 12 (22.6) |

| C | 1 (1.8) |

| TNM stage | |

| I | 0 (0) |

| II | 6 (11.2) |

| IIIA | 11 (20.8) |

| IIIB | 3 (5.7) |

| IIIC | 6 (11.2) |

| IV | 24 (45.3) |

| Okuda stage | |

| I | 27 (51.9) |

| II | 16 (30.8) |

| III | 1 (1.9) |

| BCLC stage | |

| A | 2 (3.9) |

| B | 7 (13.5) |

| C | 37 (71.2) |

| D | 1 (1.9) |

| Extrahepatic metastasis | |

| Yes | 25 (47.2) |

| No | 28 (52.8) |

| Portal vein thrombosis | |

| Yes | 26 (49.1) |

| No | 26 (49.1) |

| Unknown | 1 (1.8%) |

| Site of extrahepatic metastasis | |

| Lung | 11 (21.2) |

| Bone | 6 (11.5) |

| Brain | 1 (1.9) |

| Others | 7 (13.5) |

| Prior therapy | |

| Surgery | 12 (22.6) |

| TACE | 16 (30.2) |

| TAE | 13 (24.5) |

| Radiation therapy | 10 (18.9) |

| RFA | 10 (18.9) |

| No therapy | 10 (18.9) |

| Duration of treatment, mo | |

| Median | 6.0 (range, 1.5-53.9) |

| AFP level | |

| > 400 ng/mL | 31 (58.5) |

| < 400 ng/mL | 22 (41.5) |

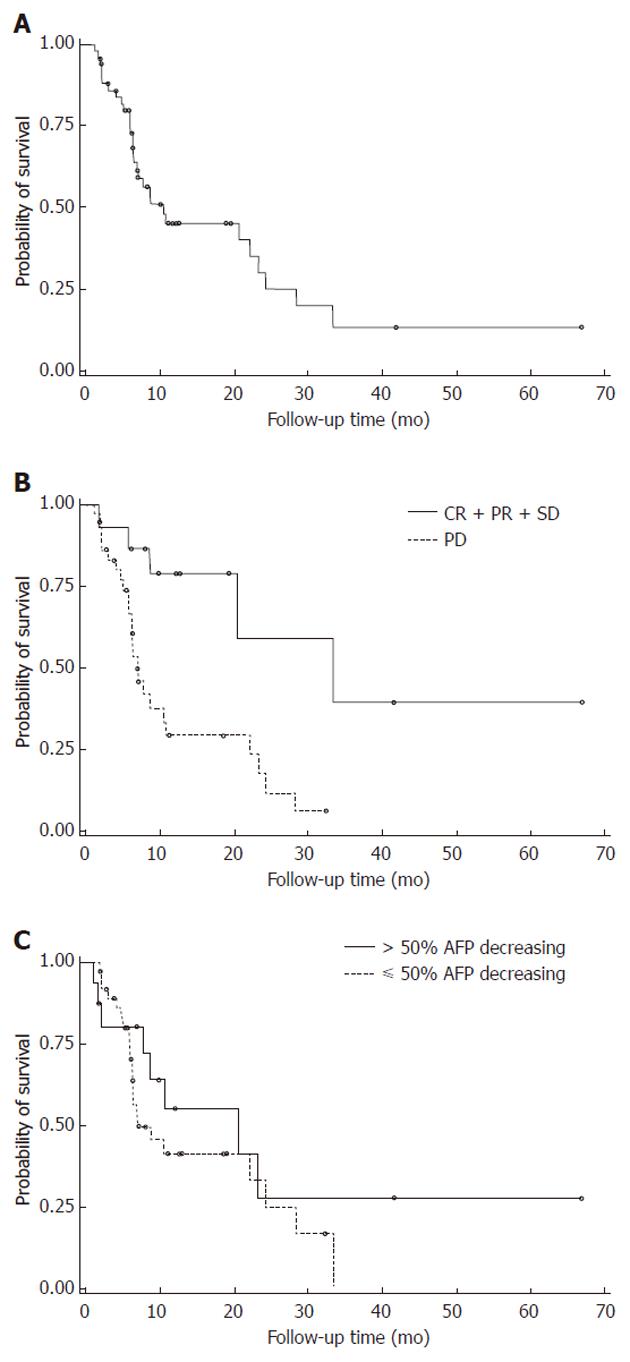

Of the 53 patients, one had a complete response (CR, 2.9%) to thalidomide, five had a partial response (PR, 9.4%) and nine were classified as stable disease (SD, 17.0%). The remaining 38 patients had disease that continued to progress after the thalidomide treatments. The objective response rate was 11.3% (95% CI: 4.3-23.0), and the disease control rate (CR + PR + SD) was 28.3% (95% CI: 17.8-42.4). The median overall survival rate was 10.5 mo (95% CI: 6.9-23.3). The 1- and 2-year survival rates were 45% and 20%, respectively. Sixteen patients (30.2%) showed more than a 50% decrease in their serum AFP levels below the baseline and showed a better response rate (31.3%), disease control rate (43.8%), and overall survival time (20.7 mo) (Table 2, Figure 1). The prognostic factors for the response rate, disease control rate, and overall survival in HCC patients receiving thalidomide are listed in Table 3. Multivariate analysis showed that almost all of these patients qualified as having independent prognostic factors for the efficacy analysis. The only significant difference in the efficacy activity was an AFP decrease of > 50% after treatment. The median overall survival time of the patients who registered > 50% AFP decrease was 20.7 mo, with a response rate of 31.3% and a disease control rate of 43.8%. The median overall survival time of those patients with a < 50% AFP decrease was 7.1 mo, with a response rate of 2.7% and a disease control rate of 21.6% (Table 3, Figure 1). Table 4 is a comparison of the patients who responded and the patients whose disease progressed. Patients in the CR + PR + SD group had a significantly longer survival time (33.3 mo) than those in the progressive disease (PD) group (6.9 mo, P < 0.003) (Figure 1).

| Overall objective response, n = 53, (%) | |

| CR | 1 (2.9) |

| PR | 5 (9.4) |

| SD | 9 (17.0) |

| PD | 38 (44.1) |

| Objective response rate | 6 (11.3), 95% CI: 4.3-23.0 |

| Disease control rate | 15 (28.3), 95% CI: 17.8-42.4 |

| Overall survival, mo | |

| Median | 10.5, 95% CI: 6.9-23.3 |

| 1-year survival | (45) |

| 2-year survival | (20) |

| A decrease in AFP > 50% after treatment | |

| Yes | 16 (30.2) |

| No | 37 (69.8) |

| Variables | P value | |

| Overall response rate n (%) | ||

| Child-Pugh classification | ||

| A | 3/30 (10.0) | 1.0001 |

| B and C | 3/23 (13.0) | |

| Okuda staging | ||

| Stage 1 | 2/27 (7.4 | 0.3441 |

| Stage 2 | 3/16 (18.8) | |

| AFP level | ||

| > 400 ng/mL | 1/31 (3.2) | 0.0711 |

| < 400 ng/mL | 5/22 (22.7) | |

| A decrease in AFP > 50% after treatment | ||

| Yes | 5/16 (31.3) | 0.0071 |

| No | 1/37 (2.7) | |

| Disease control rate n (%) | ||

| Child-Pugh Classification | ||

| A | 6/30 (20.0) | 0.2181 |

| B and C | 9/23 (39.1) | |

| Okuda staging | ||

| Stage 1 | 6/27 (22.2) | 0.7191 |

| Stage 2 | 5/16 (31.3) | |

| AFP level | ||

| > 400 ng/mL | 7/31 (22.6) | 0.3571 |

| < 400 ng/mL | 8/22 (36.4) | |

| A decrease in AFP > 50% after treatment | ||

| Yes | 7/16 (43.8) | 0.0711 |

| No | 8/37 (21.6) | |

| Overall survival, mo | ||

| Child-Pugh Classification | ||

| A | 8.8 | 0.9222 |

| B and C | 10.8 | |

| Okuda staging | ||

| Stage 1 | 22.2 | 0.0752 |

| Stage 2 | 6.9 | |

| AFP level | ||

| > 400 ng/mL | 10.8 | 0.6792 |

| < 400 ng/mL | 6.5 | |

| A decrease in AFP > 50% after treatment | ||

| Yes | 20.7 (95% CI: 1.7-NA) | 0.3072 |

| No | 7.1 (95% CI: 6.3-24.3) |

| Characteristic | CR | PR | SD | PD | CR + PR + SD | P valuea |

| AFP level | 0.357 | |||||

| > 400 ng/mL | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | 6 (19.4) | 24 (77.4) | 7 (22.6) | |

| < 400 ng/mL | 1 (4.6) | 4 (18.2) | 3 (13.6) | 14 (63.6) | 8 (36.4) | |

| A decrease in AFP > 50% after treatment | 1 (6.3) | 4 (25.0) | 2 (12.5) | 9 (56.3) | 7 (43.8) | 0.182 |

| Overall survival, mo | 66.8 | NA | 20.7 (95% CI: 20.7-33.3) | 6.9 (95% CI: 6.3-10.8) | 33.3 (95% CI: 20.7-NA) | 0.003b |

Thalidomide has been used in the treatment of advanced HCC patients. Hsu et al[10] reported an overall response rate of 6.3% with an overall survival time of 18.7 wk when an escalating dose (100-600 mg/d) of thalidomide was used for the treatment of advanced HCC. Patt et al[14] also showed a 5% overall response rate with a 6.8-mo overall survival time when a high dose (400-1000 mg/d) of thalidomide was used. In a phase II study[12], high-dose (200-800 mg/d) single-agent thalidomide demonstrated a response rate of 3.9% with an overall survival time of 123 d. The first retrospective study to analyze the efficacy and tolerability of fixed low-dose thalidomide in the treatment of advanced HCC patients[15] showed that low-dose thalidomide has a comparable single-agent activity (response rate of 5%, with an overall survival time of 4.3 mo) but fewer treatment-related toxicities than high-dose thalidomide when treating advanced HCC patients. Patients treated with low-dose thalidomide have similar overall survival times compared to patients treated with chemotherapeutic agents, with a far better toxicity profile and less hematological toxicity (no grade 3/4 neutropenia or thrombocytopenia)[15,16]. The largest randomized phase III trial for HCC (the SHARP trial) showed better progression free survival and overall survival times with sorafenib than with placebo[4]. The primary drug-related adverse events were dermatological (constitutional and hand-foot skin reactions) and gastrointestinal[4,17]. The toxicity of sorafenib is a serious problem because approximately 50% of the patients had to interrupt or stop their treatment because of sorafenib-induced toxicity. The tolerance of low-dose thalidomide in HCC patients may be worth further investigation.

The treatment of hepatoma with thalidomide appears to be feasible. A complete response was rare with thalidomide treatment of HCC; the PR rate was 5%-10%, and the SD rate was approximately 37%[10,12,14], depending on the duration of observation, cancer stage, and the definition of stability. In our study, one patient had complete remission; the PR rate was 9.4%, and the SD rate was 17%. One CR patient received thalidomide alone after a TACE therapy failure; the duration of the treatment was 53.9 mo, the patient had no recurrence, and he is still alive (66.8 mo post-treatment). The most interesting finding was the AFP decrease from 11 005.3 ng/mL at diagnosis to < 20 ng/mL (Table 4). Of the 5 patients with partial responses, 2 had prior TACE treatments, 2 had RT, 1 had PEI and 1 had systemic therapy. The median survival time among these patients was 502 d (range, 248-1263 d), and 3 of them are still alive. The median survival time of patients with stable disease was 412 d (range, 60-1013 d).

Patients in the CR + PR + SD group had a significantly longer survival time (33.3 mo) than those in the PD group (6.9 mo, P < 0.003). Thalidomide may offer HCC stabilization and prolong survival, especially in patients with stabilization. Survival time should be the focus of future clinical trials of thalidomide therapy. In this study, we evaluated the clinical implication of the AFP tumor marker response in assessing the therapeutic effects of thalidomide in HCC. The results showed that the AFP response was an independent prognostic factor for the response rate, disease control rate, and overall survival time. We also identified patients with more than or less than a 50% decrease in serum AFP levels from the baseline, which made a significant difference in their response rates (31.3% vs 2.7%, P = 0.007). There was a better trend in the disease control rate (43.8%) and overall survival time (20.7 mo) when there was greater than a 50% AFP decrease (Table 3). The AFP response may correlate with the biological response and, consequently, predict the survival benefits of thalidomide in HCC.

In conclusion, thalidomide has shown modest clinical activity, including response and survival, and was safely administered to patients with advanced HCC. Because the present study is retrospective in nature with a relatively small number of patients, a larger, randomized phase II/III study is needed to clearly define the role of single-agent thalidomide in the treatment of HCC as an alternative to the expensive molecular-targeted therapies.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most frequent primary liver cancer, the fifth most common malignancy worldwide (with over 700 000 new cases per year), and the third most common cause of cancer deaths. However, for advanced-stage patients, no standard treatment was established until the positive result of the Study of Heart and Renal Protection study. However, there are many new modalities of treatment with more favorable therapeutic indices that are suitable for patients with advanced HCC.

HCC is a hypervascular tumor that is one of the most antiangiogenic and angiogenesis-dependent tumors. Recently, thalidomide was shown to inhibit the angiogenesis of cancer cells and studies have reported modest responses to this therapy in advanced HCC. The authors retrospectively analyzed the records of HCC patients who received thalidomide in combination with other therapies to determine whether thalidomide was effective.

Studies published on the efficacy of thalidomide in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma have reported modest responses to the therapy with acceptable toxicity. Some of them highlighted the alpha fetoprotein (AFP) tumor marker response in assessing the therapeutic effects of thalidomide in HCC. In this study, the authors concluded thalidomide showed modest clinical activity, including response and survival, and was safely administered to patients with advanced HCC. Furthermore, they also identified patients with more than or less than a 50% decrease in serum AFP levels from the baseline, which made a significant difference in their response rates.

The results showed that the AFP response was an independent prognostic factor for the response rate, disease control rate, and overall survival time. The AFP response may correlate with the biological response and, consequently, predict the survival benefits of thalidomide in HCC.

This is an interesting and well written manuscript summarising the effects of thalidomide on HCC patients in a retrospective study.

| 1. | Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2003;362:1907-1917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3241] [Cited by in RCA: 3295] [Article Influence: 143.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Available from: http://cph.ntu.edu.tw/. |

| 3. | Venook AP. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: too many options? J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:1323-1334. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul JL, Forner A. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9016] [Cited by in RCA: 10547] [Article Influence: 585.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 5. | Ikeda K, Saitoh S, Koida I, Tsubota A, Arase Y, Chayama K, Kumada H. Diagnosis and follow-up of small hepatocellular carcinoma with selective intraarterial digital subtraction angiography. Hepatology. 1993;17:1003-1007. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Yamaguchi R, Yano H, Iemura A, Ogasawara S, Haramaki M, Kojiro M. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 1998;28:68-77. [PubMed] |

| 8. | D'Amato RJ, Loughnan MS, Flynn E, Folkman J. Thalidomide is an inhibitor of angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4082-4085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1715] [Cited by in RCA: 1710] [Article Influence: 53.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kruse FE, Joussen AM, Rohrschneider K, Becker MD, Völcker HE. Thalidomide inhibits corneal angiogenesis induced by vascular endothelial growth factor. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1998;236:461-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hsu C, Chen CN, Chen LT, Wu CY, Yang PM, Lai MY, Lee PH, Cheng AL. Low-dose thalidomide treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology. 2003;65:242-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang TE, Kao CR, Lin SC, Chang WH, Chu CH, Lin J, Hsieh RK. Salvage therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma with thalidomide. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:649-653. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Lin AY, Brophy N, Fisher GA, So S, Biggs C, Yock TI, Levitt L. Phase II study of thalidomide in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103:119-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, Verweij J, Van Glabbeke M, van Oosterom AT, Christian MC. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12751] [Cited by in RCA: 13142] [Article Influence: 505.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 14. | Patt YZ, Hassan MM, Lozano RD, Nooka AK, Schnirer II, Zeldis JB, Abbruzzese JL, Brown TD. Thalidomide in the treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase II trial. Cancer. 2005;103:749-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Yau T, Chan P, Wong H, Ng KK, Chok SH, Cheung TT, Lam V, Epstein RJ, Fan ST, Poon RT. Efficacy and tolerability of low-dose thalidomide as first-line systemic treatment of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology. 2007;72 Suppl 1:67-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chuah B, Lim R, Boyer M, Ong AB, Wong SW, Kong HL, Millward M, Clarke S, Goh BC. Multi-centre phase II trial of Thalidomide in the treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Acta Oncol. 2007;46:234-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, Luo R, Feng J, Ye S, Yang TS. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3854] [Cited by in RCA: 4743] [Article Influence: 263.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Peer reviewer: Dr. Thomas Kietzmann, Professor, Department of Biochemistry, University of Oulu, Oulu 90014, Finland

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Li JY