Published online Feb 7, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i5.453

Revised: August 25, 2011

Accepted: August 31, 2011

Published online: February 7, 2012

AIM: To share our experience of the management and outcomes of patients with pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis (PCI).

METHODS: The charts of seven patients who underwent surgery for PCI between 2001 and 2009 were reviewed retrospectively. Clinical features, diagnoses and surgical interventions of patients with PCI are discussed.

RESULTS: Seven patients with PCI (3 males, 4 females; mean age, 50 ± 16.1 years; range, 29-74 years) were analyzed. In three of the patients, abdominal pain was the only complaint, whereas additional vomiting and/or constipation occurred in four. Leukocytosis was detected in four patients, whereas it was within normal limits in three. Subdiaphragmatic free air was observed radiologically in four patients but not in three. Six of the patients underwent an applied laparotomy, whereas one underwent an applied explorative laparoscopy. PCI localized to the small intestine only was detected in four patients, whereas it was localized to the small intestine and the colon in three. Three patients underwent a partial small intestine resection and four did not after PCI was diagnosed. Five patients were diagnosed with secondary PCI and two with primary PCI when the surgical findings and medical history were assessed together. Gastric atony developed in one case only, as a complication during a postoperative follow-up of 5-14 d.

CONCLUSION: Although rare, PCI should be considered in the differential diagnosis of acute abdomen. Diagnostic laparoscopy and preoperative radiological tests, including computed tomography, play an important role in confirming the diagnosis.

- Citation: Arikanoglu Z, Aygen E, Camci C, Akbulut S, Basbug M, Dogru O, Cetinkaya Z, Kirkil C. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis: A single center experience. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(5): 453-457

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i5/453.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i5.453

Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis (PCI) is a relatively uncommon condition, characterized by the presence of multiple gas-filled cysts within the wall of the gastrointestinal tract[1-12]. The term “pneumatosis intestinalis” was first used by Duo Vernoi while observing autopsy specimens in 1730. The entity defined by Duo Vernoi is what we now know as primary PCI. The term “secondary PCI” was termed by Koss in 1952, who analyzed 213 pathological specimens and attributed 85% of the cases to a secondary disease[1,2].

One of the pathognomonic features of PCI is pneumoperitoneum without peritoneal irritation as a result of a cyst rupture. In contrast, air retention leading to acute abdominal findings may be seen in some cases[3].

PCI is a radiological or exploratory entity, not a disease, and the underlying causes are numerous. PCI may develop either after a benign procedure, such as endoscopy, or from an unknown cause (primary or idiopathic). In some cases, a more serious disease, such as secondary necrotizing enterocolitis, may be the cause. No clear consensus has yet been established, although many mechanical, bacterial, and pulmonary hypotheses have been proposed regarding the etiopathogenesis of PCI[4]. PCI usually does not lead to clinical findings and may disappear spontaneously in cases in which the primary disease is treated. Steroids, an elemental diet, hyperbaric oxygen, antibiotics, and surgery have been used as treatments. In this study, we describe seven PCI cases, which were diagnosed and treated at our clinic.

Seven patients were admitted to Firat University Faculty of Medicine, Department of Surgery, Emergency Unit, between January 2001 and August 2009. Their medical records were evaluated retrospectively to obtain follow-up and clinical data, including age, sex, initial complaints, medical histories, white blood cell, abdominal and thoracic radiography, intraoperative findings, surgical intervention, duration of hospital stay, complications and follow-up time (Table 1). Preoperative tests were performed, including routine biochemistry and thoracic and abdominal radiography. Five of the patients had findings consistent with an acute abdomen and were operated on. Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) was performed in one case due to vague abdominal findings. The CT findings were consistent with a rectal perforation. Abdominal ultrasonography (USG) was also used in one patient who had marked tenderness in the right upper quadrant. All patients operated on underwent emergent surgery, and all patients were diagnosed with PCI intraoperatively. Surgical team consensus was used to determine which patients would be resected after a laparotomy and/or laparoscopic exploration. The affected segment was resected in cases with suspicion of bowel perforation and ischemia, whereas no additional surgical intervention was performed in cases in which only PCI was detected. The primary or secondary nature of the PCI was determined by considering the medical history and preoperative findings. Cases with no underlying predisposing disease were considered primary or idiopathic PCI, whereas those accompanying some disease, such as appendicitis, Crohn’s disease, pyloric stenosis, necrotizing enterocolitis, peptic ulcers, cystic fibrosis, or chronic obstructive lung disease, were regarded as secondary PCI. Follow-up time was determined from the time of surgery to the last visit to our outpatient clinic.

| No. | Age | Sex | Complaint | Medical history | WBC | Radiologic tools | Loc. | Etiology | Surgical intervention | Length of hospital stay (d) | Postoperative complication | Follow-up (mo) |

| 1 | 29 | F | AP + V | Endoscopy | 11.1 | X-ray, CT4 | SB | Secondary | Ileal resection + anastomosis | 7 | No | 14 |

| 2 | 48 | M | AP + V + C2 | Peptic ulcer perforation | NR | X-ray | SB | Secondary | Ileal resection + anastomosis | 14 | Gastric atony | 21 |

| 3 | 71 | M | AP + V + C2 | CLL (CT3) | 35 | X-ray | SB | Secondary | Laparatomy | 5 | No | 8 |

| 4 | 74 | F | AP | Normal | NR | X-ray, US | SB | Secondary | Cholecystectomy + choledocotomy + drainage | 11 | No | 23 |

| 5 | 53 | F | AP | Colonoscopy | NR | X-ray | SB + C1 | Secondary | Laparatomy | 8 | No | 18 |

| 6 | 34 | F | AP + V | Normal | 23 | X-ray | SB + C1 | Primary | Ileal resection + anastomosis | 10 | No | 12 |

| 7 | 41 | M | AP | Normal | 16 | X-ray | SB + C1 | Primary | Laparoscopic exploration | 7 | No | 9 |

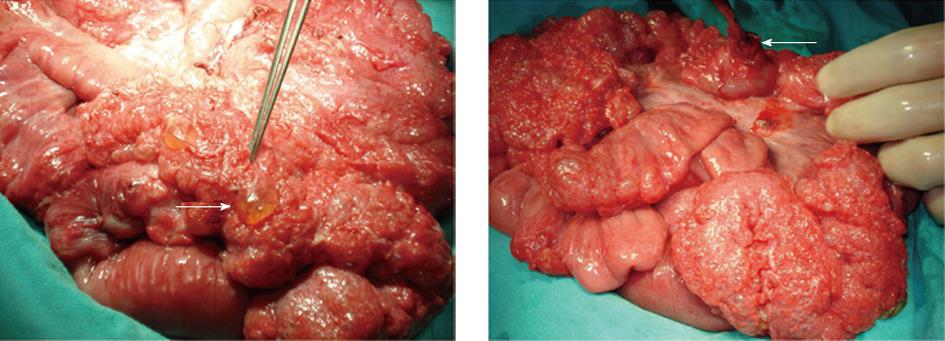

Data for seven patients with PCI (3 males, 4 females; age, 50 ± 16.1 years (mean ± SD); range, 29-74 years) were analyzed retrospectively. Of the patients who presented at the Emergency Unit, three had severe abdominal pain, two had abdominal pain and vomiting, and two had abdominal pain, vomiting, and constipation. Liver and renal function tests as well as electrolyte values were normal in all patients, while marked leukocytosis was detected in four. Exam findings in six of the patients were consistent with acute peritonitis, whereas no findings other than minimal tenderness were noted in one patient (female, aged 29 years). Subdiaphragmatic free air was detected on plain thoracic and abdominal radiographs in four patients. Abdominal USG used in one patient (female, aged 74 years), who had marked tenderness in the right upper quadrant, revealed cholecystitis together with an image consistent with a stone in the lower tip of the choledoch. An abdominal CT of a 29-year-old female patient with vague findings revealed free air extending into the retroperitoneum, indicating a rectal perforation. This patient was diagnosed with acute abdomen and was scheduled for urgent surgery. A PCI diagnosis was established in seven patients after a laparotomy in six and a laparoscopic exploration in one. An appearance consistent with PCI was observed in the small intestine of four patients and in the small intestine and colon of three (Figure 1A). A small intestinal perforation was observed in only one (female, aged 34 years) of these cases (Figure 1B). PCI was detected incidentally in a 74-year-old female patient who was scheduled for bile duct surgery (cholecystectomy and choledoch exploration only). Three patients underwent a partial small intestinal resection and anastomosis, while four had no additional surgical procedures after PCI was diagnosed. All patients were given 3 L/min oxygen during the first 3 postoperative days. During the 5-14 d clinical follow-up, a 48-year-old male developed gastric atony, whereas the remaining six patients were discharged with no complications. No additional complications were observed in any of the patients during the 15 ± 5.4 mo (range, 8-23 mo) follow-up. After considering the surgical findings and medical and surgical histories, five of these patients had secondary PCI and two had primary PCI.

PCI is a rare condition characterized by multilocular gas-filled cysts localized in the submucosa and subserosa of the gastrointestinal tract[5,13-17]. The term “pneumatosis intestinalis” was first used by Duo Vernoi during postmortem observations. A PCI diagnosis in surviving patients was first established by Hahn in 1899. A PCI diagnosis via preoperative radiological findings was first described by Baumann-Schender in 1939. The condition originally described by Duo Vernoi is what we now consider primary PCI. The term “secondary PCI” was coined by Koss in 1952, who analyzed 213 pathological specimens and attributed 85% of the cases to a secondary disease[1-3].

Several hypotheses have been proposed regarding the development of PCI, although its pathogenesis is still controversial. Two main hypotheses regarding the fundamental pathogenesis of PCI are mechanical and bacterial[17]. The mechanical hypothesis postulates that PCI develops when defects in the mucosa, in combination with increased intraluminal pressure, allow gas to infiltrate the gastrointestinal (GI) tract wall. A subgroup of patients with severe pulmonary conditions may present with PCI arising from pulmonary causes, such as cough and rapid changes in intra-abdominal pressure. The bacterial hypothesis proposes that PCI develops when gas-producing bacteria gain entry into the GI tract wall and produce gas pockets. Much of the supporting evidence for these two hypotheses is derived from observational studies, and mechanical and bacterial mechanisms may occur simultaneously[4,6,7].

Although PCI may occur anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract, from the esophagus to the rectum, it is usually seen in the intestine. A previous study reported that 20%-51.6% of all PCI cases involve the small intestine, 36%-78% involve the colon, and 2%-22% include both the small intestine and colon. The small intestine was involved in 57.1% of the cases we presented here and 42.9% involved the small intestine and the colon[1,2,6,8].

PCI is not a disease but a clinical entity. The etiology can be classified by considering factors thought to play a role in its development. Based on this notion, PCI can be divided into primary and idiopathic (15%) or secondary (85%) type[9]. No identifiable underlying or predisposing factor is present in the primary or idiopathic type. However, numerous gastrointestinal diseases, including appendicitis, necrotizing enterocolitis, Crohn’s disease, pyloric stenosis, ulcerative colitis, diverticular disease, necrotizing enterocolitis, gastroduodenal ulcer, and sigmoid volvulus, may accompany PCI as a secondary cause. PCI has also been reported as accompanying some non-gastrointestinal diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, collagen tissue diseases, acquired immune deficiency syndrome, and glucocorticoid use. PCI cases secondary to surgical or endoscopic trauma have also been reported[10,11].

Lesions are usually localized to the left hemicolon or its mesentery or to the submucosal layer and are frequently characterized by segmentary involvement in the primary form of the disease. However, involvement is usually subserosal in the secondary form, and occurs in the stomach, small intestine, and right colon, usually in a generalized or segmented pattern[7].

The incidence of PCI is unknown, because it is usually asymptomatic. Symptoms, if any, are usually secondary to an underlying disease. Together with non-specific symptoms, such as abdominal discomfort, diarrhea, constipation, rectal bleeding, tenesmus, or loss of weight, severe complications, including volvulus, intestinal obstruction, tension pneumoperitoneum, bleeding, intussusception, and intestinal perforation may be seen in 3% of patients[18-23].

Radiological tools are important for diagnosing PCI. These include plain radiographs, USG, barium series, CT, CT-colonoscopy, magnetic resonance imaging and MRI-colonography, endoscopy, and colonoscopy[19,20]. X-ray is of great importance, because it is readily available in every emergency room. Cysts usually appear as radiolucent shadows, similar to a bunch of grapes, close to the intestinal lumen on radiographs. Free air underneath the diaphragm may be seen if these cysts perforate. An appearance of bulging into the lumen as a filling defect is seen on barium-colon radiographs[15,23]. Linear or spot-like hyperechoic images may be seen in the intestinal wall on USG. CT is the most useful method for diagnosing PCI and is important because it provides data on other abdominal pathologies. However, CT may not provide data on intestinal ischemia and necrosis[1,4,7,12]. The colonoscopic findings may be similar to multiple polyposis or collections of submucosal tumors, but subserous pneumatosis may go undetected[20]. A laparoscopic exploration is quite useful to confirm a PCI diagnosis, if the physical examination findings are suspicious, and particularly in cases that are not preoperatively diagnosed clearly using the above-mentioned radiological methods. Diagnostic laparoscopy provides the convenience of converting to open surgery as well as confirming the diagnosis.

When presence of such an entity is confirmed radiologically, gastroenterologic surgeons begin to feel annoyance. The answer to the question, “What should we do to these patients?” is correlated with the experience of each surgeon on that entity. The approach to a patient with PCI should be determined by evaluating the underlying causes and exam findings together. A specific treatment is not recommended in asymptomatic patients who are detected as having PCI radiologically and whose examination findings are negative. Conservative approaches, including nasogastric decompression, intestinal rest, antibiotic therapy and oxygen, are recommended for patients with positive examination findings and normal biochemical parameters who are confirmed radiologically to have no intestinal ischemia or perforation[24]. Applying 250 mmHg PO2 pressure or 70% oxygen inhalation for 5 d or 2.5 atmospheres of hyperbaric oxygen pressure for 150 min/d for 3 consecutive days can lead to resolution of gas collection within a cyst[10,13,24,25]. An urgent laparotomy is necessary in cases of intestinal ischemia, obstruction, intestinal bleeding, or peritonitis[14,16]. Definitive surgery should be performed during a laparotomy if necrosis, perforation, or marked ischemia is observed in the intestine. Furthermore, no additional surgical procedures should be conducted unless other pathology is detected in addition to serosal or subserosal air cysts.

Consequently, clinical suspicion, physician experience, radiological tools, and team spirit are important in terms of the approach to PCI. When and how to treat these patients is the main issue to lower mortality and morbidity.

Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis (PCI) is a pathologic condition defined as infiltration of gas into the wall of the gastrointestinal tract.

The authors retrospectively reviewed the diagnosis and management of seven patients with pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis.

Clinical suspicion, physician experience, radiological tools and team spirit are important in terms of the approach to PCI. When and how to treat these patients is the main issue to lower mortality and morbidity.

According to authors’ opinion, specific treatment is not recommended in asymptomatic patients who are detected to have PCI radiologically and whose examination findings are negative. However, laparotomy is necessary in cases of intestinal ischemia, obstruction, intestinal bleeding or peritonitis

The primary and idiopathic or secondary nature of the PCI is determined by considering the medical history and by preoperative examination. Cases with no underlying predisposing disease are considered primary PCI, whereas those accompanying some disease, such as appendicitis, Crohn’s disease, pyloric stenosis, necrotizing enterocolitis, peptic ulcers, cystic fibrosis or chronic obstructive lung disease, are regarded as secondary PCI.

This is a well written report on a small series of a rare entity. It has some educational value in the presentation and the figures.

| 1. | Morris MS, Gee AC, Cho SD, Limbaugh K, Underwood S, Ham B, Schreiber MA. Management and outcome of pneumatosis intestinalis. Am J Surg. 2008;195:679-682; discussion 682-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Greenstein AJ, Nguyen SQ, Berlin A, Corona J, Lee J, Wong E, Factor SH, Divino CM. Pneumatosis intestinalis in adults: management, surgical indications, and risk factors for mortality. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1268-1274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Voboril R. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis--a review. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove). 2001;44:89-92. [PubMed] |

| 4. | St Peter SD, Abbas MA, Kelly KA. The spectrum of pneumatosis intestinalis. Arch Surg. 2003;138:68-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Bilici A, Karadag B, Doventas A, Seker M. Gastric pneumatosis intestinalis associated with malignancy: an unusual case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:758-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wayne E, Ough M, Wu A, Liao J, Andresen KJ, Kuehn D, Wilkinson N. Management algorithm for pneumatosis intestinalis and portal venous gas: treatment and outcome of 88 consecutive cases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:437-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bolukbas FF, Bolukbas C. Pnomatozis sistoides intestinalis. Guncel Gastroenteroloji. 2004;8:182-185. |

| 8. | Jamart J. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis. A statistical study of 919 cases. Acta Hepatogastroenterol (Stuttg). 1979;26:419-422. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Kim KM, Lee CH, Kim KA, Park CM. CT Colonography of pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis. Abdom Imaging. 2007;32:602-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Sakurai Y, Hikichi M, Isogaki J, Furuta S, Sunagawa R, Inaba K, Komori Y, Uyama I. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis associated with massive free air mimicking perforated diffuse peritonitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6753-6756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Türk E, Karagülle E, Ocak I, Akkaya D, Moray G. [Pneumatosis intestinalis mimicking free intraabdominal air: a case report]. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2006;12:315-317. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Ho LM, Paulson EK, Thompson WM. Pneumatosis intestinalis in the adult: benign to life-threatening causes. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:1604-1613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Goel A, Tiwari B, Kujur S, Ganguly PK. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis. Surgery. 2005;137:659-660. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Mclaughlin SA, Nguyen JH. Conservative management of nongangrenous esophageal and gastric pneumatosis. Am Surg. 2007;73:862-864. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Di Giorgio A, Sofo L, Ridolfini MP, Alfieri S, Doglietto GB. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis. Lancet. 2007;369:766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kala Z, Hermanova M, Kysela P. Laparoscopically assisted subtotal colectomy for idiopathic pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis. Acta Chir Belg. 2006;106:346-347. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Yellapu RK, Rajekar H, Martin JD, Schiano TD. Pneumatosis intestinalis and mesenteric venous gas - a manifestation of bacterascites in a patient with cirrhosis. J Postgrad Med. 2011;57:42-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Frossard JL, Braude P, Berney JY. Computed tomography colonography imaging of pneumatosis intestinalis after hyperbaric oxygen therapy: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2011;5:375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Donati F, Boraschi P, Giusti S, Spallanzani S. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis: imaging findings with colonoscopy correlation. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:87-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tsujimoto T, Shioyama E, Moriya K, Kawaratani H, Shirai Y, Toyohara M, Mitoro A, Yamao J, Fujii H, Fukui H. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis following alpha-glucosidase inhibitor treatment: a case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6087-6092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Koreishi A, Lauwers GY, Misdraji J. Pneumatosis intestinalis: a challenging biopsy diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1469-1475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Doumit M, Saloojee N, Seppala R. Pneumatosis intestinalis in a patient with chronic bronchiectasis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22:847-850. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Nagata S, Ueda N, Yoshida Y, Matsuda H. Pneumatosis coli complicated with intussusception in an adult: report of a case. Surg Today. 2010;40:460-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mizoguchi F, Nanki T, Miyasaka N. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis following lupus enteritis and peritonitis. Intern Med. 2008;47:1267-1271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Togawa S, Yamami N, Nakayama H, Shibayama M, Mano Y. Evaluation of HBO2 therapy in pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2004;31:387-393. [PubMed] |

Peer reviewer: Kjetil Soreide, MD, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Surgery, Stavanger University Hospital, Armauer Hansensvei 20, PO Box 8100, N-4068 Stavanger, Norway

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Li JY