Published online Dec 7, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i45.6677

Revised: August 28, 2012

Accepted: September 12, 2012

Published online: December 7, 2012

Plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) is a rare aggressive B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder, which has been characterized by the World Health Organization as a new entity. Although PBL is most commonly seen in the oral cavity of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients, it can also be seen in extra-oral sites in immunocompromised patients who are HIV-negative. Here we present a rare case of PBL of the small intestine in a 55-year-old HIV-negative male. Histopathological examination of the excisional lesion showed a large cell lymphoma with plasmacytic differentiation diffusely infiltrating the small intestine and involving the surrounding organs. The neoplastic cells were diffusely positive for CD79a, CD138 and CD10 and partly positive for CD38 and epithelial membrane antigen. Approximately 80% of the tumor cells were positive for Ki-67. A monoclonal rearrangement of the kappa light chain gene was demonstrated. The patient died approximately 1.5 mo after diagnosis in spite of receiving two courses of the CHOP chemotherapy regimen. In a review of the literature, this is the first case report of PBL with initial presentation in the small intestine without HIV and Epstein-Barr virus infection, and a history of hepatitis B virus infection and radiotherapy probably led to the iatrogenic immunocompromised state.

- Citation: Wang HW, Yang W, Sun JZ, Lu JY, Li M, Sun L. Plasmablastic lymphoma of the small intestine: Case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(45): 6677-6681

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i45/6677.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i45.6677

Plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) is a distinct, aggressive B-cell neoplasm that shows diffuse proliferation of large neoplastic cells resembling B-immunoblasts with an immunophenotype of plasma cells[1]. It was originally described in the oral cavity in the clinical setting of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, but may occur in other, predominately extra-oral sites, and these have been reflected in the current/revised 2008 World Health Organization classification[2]. Extra-oral PBL has been reported in various locations[3-6]; however PBL of the small intestine was extremely rare. Here we present a rare case of PBL of the small intestine in an HIV-negative individual and review the literature.

A 55-year-old man presented with generalized abdominal pain, distension and vomiting for over a 1-mo period. He also described recent weight loss and anorexia. The above pathologic condition gradually became worse without relief of symptoms. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed multiple masses in the small intestine with extension to the bilateral adrenal glands. Radiographs and computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, oral and peri-oral sites showed no abnormalities, and no peripheral lymphadenopathy was noted. Routine blood examination showed hemoglobin 106 g/L, white blood cell count 6.48 × 109 /L, neutrophils 64.4%, lymphocytes 15.3%, monocytes 10.2%. Serological testing demonstrated positivity for hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antigen and HBV e-antigen, and negativity for HIV. The lactate dehydrogenase level (216 U/L) was in the normal range. Serum examination for Bence Jones’ protein and rheumatoid factor were negative. The medical history was that he had a history of infection of HBV and underwent resection of squamous cell carcinoma in the maxillary sinus, followed by two courses of radiotherapy 7 mo previously.

During surgery, multiple tumor nodules were found in the intestinal wall and mesentery of the small intestine. Surrounding organs, including adrenal glands, liver, inferior vena cava and lumbar vertebrae were involved. Tumors were excised with adjacent portions of the small intestine and bilateral adrenal glands. A 55-cm long segment of the small bowel was obtained from the resection procedure. By gross examination, there was an irregular tumor nodule, volume 10 cm × 8 cm × 6 cm, in the intestinal wall surrounding the whole enteric cavity. Multiple tumor nodules ranging from 3.5 cm to 5.5 cm in diameter could be found in the adjacent mesentery. Tumor nodules in the left and right adrenal glands measured 8.5 cm × 8 cm × 4 cm and 8 cm × 5 cm × 2.5 cm respectively. The cut surface of these tumors was grey and soft. Selected tumor tissues were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin and cut into sections which were stained with the hematoxylin and eosin for routine histology. Additional sections of paraffin-embedded tissue were used for immunohistochemical staining and in situ hybridization analysis.

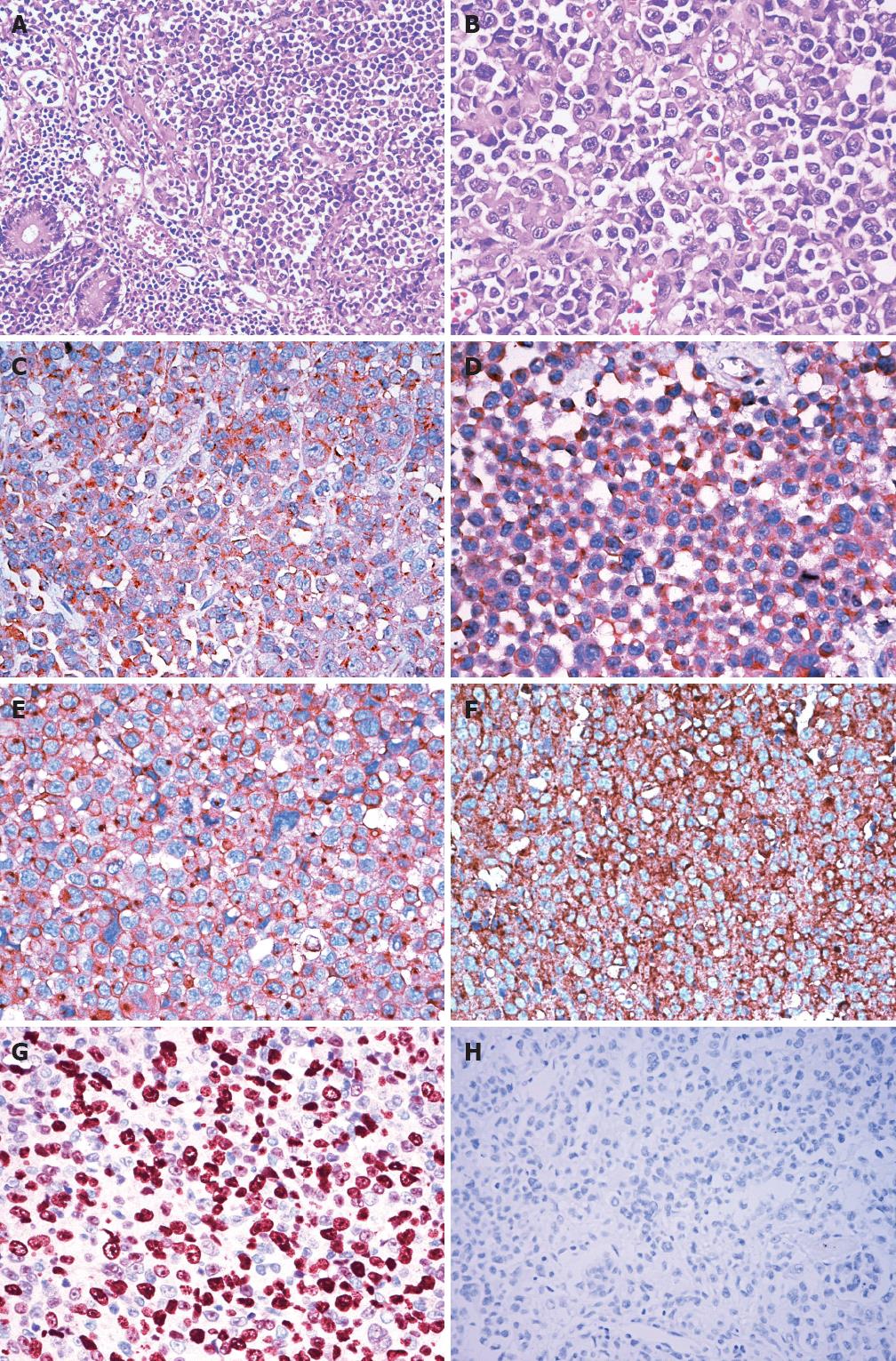

Histologically, the whole intestinal wall was diffusely infiltrated by malignant lymphocytes with abundant basophilic cytoplasm, eccentrically located pleomorphic nuclei, and single, centrally located prominent nucleoli (Figure 1A). The nuclei were round or oval or convoluted in shape and a large number of mitotic figures were apparent (Figure 1B). There were tumor emboli within the lymphatic vessels. Comprehensive necrosis of tumor cells was conspicuous. The tumor cells were scattered throughout the small intestine wall into the peripheral soft tissue and adrenal glands forming tumor nodules of different sizes. Furthermore, tumor cell proliferation in lymph node sinuses was conspicuous in the mesenteric lymph nodes.

On immunohistochemistry, the neoplastic cells were diffusely positive for CD79a (Figure 1C), CD138 (Figure 1D) and CD10 (Figure 1E), and partly positive for CD38 and epithelial membrane antigen. These cells were negative for CD45, CD20, CD3, CD30, ALK-1, Bcl-2, Bcl-6, Mum-1, CD56, HMB45, S-100, CD34, CD117 and cytokeratin. The cells showed kappa light chain restriction (Figure 1F). Nuclear proliferation rate, as assessed by Ki-67 staining, was approximately 80% (Figure 1G). Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection was not detected by in situ hybridization for EBV-encoded RNA (Figure 1H) or immunohistochemistry for EBV latent membrane protein-1. On the basis of these morphologic and immunohistochemical characteristics, the pathological diagnosis of PBL was made.

After surgery, the patient was treated with two courses of a standard CHOP (cyclophospamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) chemotherapy regimen. Unfortunately, during the second course of chemotherapy, repeat CT scans and ultrasonography revealed tumor progression with an increase in swollen cervical lymph nodes and abdominal tumor load. The patient died of multiple organ failure due to further deterioration 1.5 mo later.

As a rare entity of non-Hodgkin B cell lymphoma, PBL was first described as a specific clinicopathologic entity by Delecluse et al[7] as an aggressive B-cell lymphoma occurring in the oral cavity arising in the context of HIV infection. However, in recent years, several cases of PBL have been reported in patients without HIV infection, and several more have reported the occurrence of PBL in extra-oral sites, including the skin, subcutaneous tissue, stomach, anal mucosa or perianal area, lung, lymph node, and other regions[3-6,8,9]. The small intestine is a rare extra-oral site of involvement in PBL patients, and only two cases in HIV-infected patients have been reported previously[10,11]. In a review of the literature, this is the first case report of PBL with initial presentation in the small intestine and with multiple organ involvement in an HIV-negative individual.

As PBL is often associated with immunodeficiency, such as HIV infection, EBV plays an important role in the tumorigenesis of HIV-associated PBL. HIV infection creates a permissive environment for chronic EBV infection, with a subsequent latency that predisposes the EBV transformed B-cells to become malignant[12]. There is likely a connection between HIV-induced immunosuppression and the development of EBV-associated PBL[13]. However, recent investigation revealed that EBV infection was detected in only 17% of HIV-negative PBL cases, which suggest that this virus may not be a unique participant in the pathogenesis of PBL, especially in patients without HIV infection[14]. Cases of HIV-negative PBL have been mostly described after solid organ transplantation, in association with steroid therapy for autoimmune disease and some other types of immunosuppression[15,16]. The present patient was negative for HIV, and EBV infection was not detected by immunohistochemistry or in situ hybridization analysis, so an HBV infection and the history of radiotherapy probably led to the iatrogenic immunocompromised state.

The pathological differential diagnosis of PBL in the present case mainly included poorly differentiated primary or metastatic carcinoma, malignant melanoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), Burkitt’s lymphoma, anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), and plasmacytoma[3]. The characteristic morphology and immunophenotype of the tumor cells in conjunction with clinical features aid in the differential diagnosis (Table 1). Poorly differentiated carcinoma may be differentiated from PBL according to its consistent immunological staining for cytokeratin. Malignant melanoma can be ruled out by using S-100 protein and HMB45. GIST is a common kind of mesenchymal tumor in the small intestine, usually characterized by expression of CD34 and CD117. In terms of negative expression for CD20 and morphological appearance, the present case of PBL can be clearly identified with other aggressive B-cell lymphomas, such as DLBCL and Burkitt’s lymphoma. Histologically, the tumor resembled extranodal ALCL; however, tumor cells in ALCL are consistently immunoreactive for CD30 and usually immunoreactive for CD3 and ALK, which is different from our case. The differential diagnosis between PBL and poorly differentiated plasmacytoma is based mostly on clinical correlations, as both have similar morphological and phenotypic features[14]. The negative presence of serum monoclonal proteins and a high Ki-67/MIB-1 proliferation index help in the differential diagnosis from plasmacytoma in the present case.

| Marker | Current case | PBL | DLBCL | ALCL | BL | PC | GIST | Carcinoma | Melanoma |

| CD45 | - | ± | + | + | + | ± | - | - | - |

| CD20 | - | ± | + | - | + | - | - | - | - |

| CD79a | + | ± | + | - | + | + | - | - | - |

| CD38 | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | - |

| CD138 | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | - |

| CD3 | - | - | - | ± | - | - | - | - | - |

| CD30 | - | - | ± | + | - | - | - | - | - |

| CD10 | + | ± | ± | - | + | - | - | - | - |

| ALK-1 | - | - | ± | ± | - | - | - | - | - |

| Bcl-2 | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Mum-1 | - | ± | ± | - | - | + | - | - | - |

| EMA | + | ± | - | + | - | - | - | + | - |

| HMB45 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + |

| S-100 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + |

| CD34 | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - |

| CD117 | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - |

| Cytokeratin | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| LMP-1 | - | ± | ± | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| EBER | - | ± | ± | - | ± | - | - | ± | - |

In terms of clinical behavior, PBL is highly aggressive, with most of the patients dying in the first year after diagnosis. Most patients are at an advanced stage (III or IV) at presentation[15]. HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients with PBL have different clinicopathological characteristics, including a better response to chemotherapy and longer survival in HIV-positive patients. HIV-negative patients had a median overall survival of 9 mo vs 14 mo in HIV-positive patients[13]. Furthermore, extra-oral PBL is more commonly disseminated (57% of the patients are at stage IV) at diagnosis. Meanwhile, the loss of CD20 associated with plasmacytic differentiation and very high Ki-67 index (> 90%) conveyed a worse prognosis[9]. In our case, the primary PBL of the small intestine had infiltrated multiple organs, accordingly a clinical stage IV was assigned. The HIV-negative state, extra-oral location, absent expression of CD20 and relatively high nuclear proliferation index in tumor cells collectively contributed to the more aggressive clinical course and worse outcome of this case.

In summary, we report a rare case of extra-oral PBL involving the small intestine in a HIV-negative patient, and describe the histologic and immunophenotypic findings. A diffuse infiltrative growth, rapid mitotic rate, and necrosis are consistent with the classification of PBL as a high-grade malignant lymphoma. Because PBL does not express the more common lymphoid and/or B-cell markers, it is easy to mistake them for a poorly differentiated carcinoma or sarcoma. Thus, diagnosis of PBL is challenging, particularly when it arises in extraoral locations and in immunocompetent patients. Recognition of this entity by the pathologist and clinician is important in establishing the correct diagnosis and treatment of the patients.

| 1. | Rafaniello Raviele P, Pruneri G, Maiorano E. Plasmablastic lymphoma: a review. Oral Dis. 2009;15:38-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Stein H, Harris NL, Campo E. Plasmablastic lymphoma. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press 2008; 256-257. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Chabay P, De Matteo E, Lorenzetti M, Gutierrez M, Narbaitz M, Aversa L, Preciado MV. Vulvar plasmablastic lymphoma in a HIV-positive child: a novel extraoral localisation. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:644-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hatanaka K, Nakamura N, Kishimoto K, Sugino K, Uekusa T. Plasmablastic lymphoma of the cecum: report of a case with cytologic findings. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39:297-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Liu JJ, Zhang L, Ayala E, Field T, Ochoa-Bayona JL, Perez L, Bello CM, Chervenick PA, Bruno S, Cultrera JL. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-negative plasmablastic lymphoma: a single institutional experience and literature review. Leuk Res. 2011;35:1571-1577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tavora F, Gonzalez-Cuyar LF, Sun CC, Burke A, Zhao XF. Extra-oral plasmablastic lymphoma: report of a case and review of literature. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:1233-1236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Delecluse HJ, Anagnostopoulos I, Dallenbach F, Hummel M, Marafioti T, Schneider U, Huhn D, Schmidt-Westhausen A, Reichart PA, Gross U. Plasmablastic lymphomas of the oral cavity: a new entity associated with the human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood. 1997;89:1413-1420. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Takahashi Y, Saiga I, Fukushima J, Seki N, Sugimoto N, Hori A, Eguchi K, Fukusato T. Plasmablastic lymphoma of the retroperitoneum in an HIV-negative patient. Pathol Int. 2009;59:868-873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chuah KL, Ng SB, Poon L, Yap WM. Plasmablastic lymphoma affecting the lung and bone marrow with CD10 expression and t(8; 14)(q24; q32) translocation. Int J Surg Pathol. 2009;17:163-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Deloose ST, Smit LA, Pals FT, Kersten MJ, van Noesel CJ, Pals ST. High incidence of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection in HIV-related solid immunoblastic/plasmablastic diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leukemia. 2005;19:851-855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Taddesse-Heath L, Meloni-Ehrig A, Scheerle J, Kelly JC, Jaffe ES. Plasmablastic lymphoma with MYC translocation: evidence for a common pathway in the generation of plasmablastic features. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:991-999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Castillo J, Pantanowitz L, Dezube BJ. HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma: lessons learned from 112 published cases. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:804-809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (10)] |

| 13. | Castillo JJ, Winer ES, Stachurski D, Perez K, Jabbour M, Milani C, Colvin G, Butera JN. Clinical and pathological differences between human immunodeficiency virus-positive and human immunodeficiency virus-negative patients with plasmablastic lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51:2047-2053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lorsbach RB, Hsi ED, Dogan A, Fend F. Plasma cell myeloma and related neoplasms. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:168-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Folk GS, Abbondanzo SL, Childers EL, Foss RD. Plasmablastic lymphoma: a clinicopathologic correlation. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2006;10:8-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hernandez C, Cetner AS, Wiley EL. Cutaneous presentation of plasmablastic post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder in a 14-month-old. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:713-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Peer reviewer: Grigoriy E Gurvits, MD, Department of Gastroenterology, St. Vincent’s Hospital and Medical Center, New York Medical College, 153 West 11th Street, Smith 2, New York, NY 10011, United States

S- Editor Lv S L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Li JY