Published online Nov 21, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i43.6290

Revised: August 6, 2012

Accepted: August 14, 2012

Published online: November 21, 2012

AIM: To compare the effects of telbivudine (LDT) and entecavir (ETV) in treatment of hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-positive chronic hepatitis B by meta-analysis.

METHODS: We conducted a literature search using PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, the China National Knowledge Infrastructure, the VIP database, the Wanfang database and the Cochrane Controlled Trial Register for all relevant articles published before April 1, 2012. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing LDT with ETV for treatment of HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B were included. The data was analyzed with Review Manager Software 5.0. We used relative risk (RR) as an effect measure, and reported its 95% CI. Meta-analysis was performed using either a fixed-effect or random-effect model, based on the absence or presence of significant heterogeneity. Two reviewers assessed the risk of bias and extracted data independently and in duplicate. The analysis was executed using the main outcome parameters including hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA undetectability, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) normalization, HBeAg loss, HBeAg seroconversion, drug-resistance, and adverse reactions. Meta-analysis of the included trials and subgroup analyses were conducted to examine the association between pre-specified characteristics with the therapeutic effects of the two agents.

RESULTS: Thirteen eligible trials (3925 patients in total) were included and evaluated for methodological quality and heterogeneity. In various treatment durations of 4 wk, 8 wk, 12 wk, 24 wk, 36 wk, 48 wk, 52 wk, 60 wk and 72 wk, the rates of HBV DNA undetectability and ALT normalization in the two groups were similar, without statistical significance. At 4 wk and 8 wk of the treatment, no statistical differences were found in the rate of HBeAg loss between the two groups, while the rate in the LDT group was higher than in the ETV group at 12 wk, 24 wk, 48 wk and 52 wk, respectively (RR 2.28, 95% CI 1.16, 7.03, P = 0.02; RR 1.45, 95% CI 1.16, 1.82, P = 0.001; RR 1.45, 95% CI 1.11, 1.89, P = 0.006; and RR 1.86, 95% CI 1.04, 3.32, P = 0.04). At 4 wk, 8 wk, 60 wk and 72 wk of the treatment, there were no significant differences in the rate of HBeAg seroconversion between the two groups, while at 12 wk, 24 wk, 48 wk and 52 wk, the rate in the LDT group was higher than in the ETV group (RR 2.10, 95% CI 1.36, 3.24, P = 0.0008; RR 1.71, 95% CI 1.29, 2.28, P = 0.0002; RR 1.86, 95% CI 1.36, 2.54, P < 0.0001; and RR 1.87, 95% CI 1.21, 2.90, P = 0.005). The rate of drug-resistance was higher in the LDT group than in the ETV group (RR 3.76, 95% CI 1.28, 11.01, P = 0.02). In addition, no severe adverse drug reactions were observed in the two groups. And the rate of increased creatine kinase in the LDT group was higher than in the ETV group (RR 5.58, 95% CI 2.22, 13.98, P = 0.0002).

CONCLUSION: LDT and ETV have similar virological and biomedical responses, and both are safe and well tolerated. However, LDT has better serological response and higher drug-resistance.

- Citation: Su QM, Ye XG. Effects of telbivudine and entecavir for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(43): 6290-6301

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i43/6290.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i43.6290

Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection is a major health problem affecting over 350 million people worldwide[1,2]. CHB can lead to various life-threatening conditions, such as liver failure, liver cirrhosis (LC) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[3]. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) covalent closed circular DNA (cccDNA) is the main cause of the sustainability of the hepatitis virus, and it is difficult to completely eliminate it[4]. So the primary therapeutic goal is to sustain viral suppression. Current anti-viral medication includes interferon [interferon-alpha (IFN-α), and pegylated (PEG) IFN-α] and nucleosides or nucleoside analogues [entacavir (ETV), adefovir dipivoxil, telbivudine (LDT), and lamivudine][5]. Recent studies have shown that LDT and ETV are the strongest nucleoside analogues. LDT (β-L-2’-deoxythymidine) is an orally bioavailable L-nucleoside. It can effectively suppress HBV DNA replication, and has a higher rate of hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) seroconversion than other current oral antiviral agents[6]. However, its drug-resistance remains high[7]. ETV is a new generation nucleoside analogues. It has the advantage of higher rate of HBV DNA suppression, low drug-resistance and high safety, especially in lamivudine-resisitant CHB patients[8]. But the rates of HBeAg loss and seroconversion are very low in ETV group, which is difficult to meet the withdrawal standards. There are few systematic reviews about the comparison of LDT and ETV. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis of the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) using the Cochrane methodology to explore the efficacy of LDT and ETV for clinical treatment of HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B.

We searched PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, the VIP database, the Wanfang database and the Cochrane Controlled Trial Register for articles published up to April 1, 2012, using the following keywords: “HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B”, “telbivudine”, “entecavir”, and “ RCTs”. The reference lists of eligible studies were also searched.

The following inclusion criteria were used: (1) RCTs; (2) Articles studying HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B patients, according to diagnostic standards in “China guidelines for HBV management (2010)”[9]; (3) Studies comparing LDT (600 mg/d) with ETV (0.5 mg/d); and (4) The main outcome parameters included virological, biochemical, and serological responses [HBV DNA undetectability, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) normalization, HBeAg loss, HBeAg seroconversion, drug-resistance, and adverse reactions]. Virological response was defined as attainment of undetectable levels of HBV DNA. Determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction, the threshold of detection was 1000 copies/mL or less in each corresponding study (Table 1). Biochemical response was defined as normalization of ALT levels to below the upper limit of normal (< 40 IU/mL). HBeAg loss was defined as HBeAg levels < 1.0 S/CO, HBeAg seroconversion was defined as HBeAg loss and the presence of anti-HBeAg, determined by microparticle enzyme immunoassay or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

| Trials | Sample size (n) | Mean age (yr) | Regimen (mg/d) | Duration(wk) | Observationtime (wk) | Outcome parameters | HBV DNA undetectability (copy/mL) | |||

| LDT | ETV | LDT | ETV | LDT | ETV | |||||

| Zhao et al[12] | 36 | 36 | 34.30 | 600 | 0.5 | 48 | 24, 48 | ABDE | - | |

| Zhu et al[13] | 30 | 30 | 28.00 ± 9.10 | 31.80 ± 7.10 | 600 | 0.5 | 24 | 12, 24 | ABCDE | 1000 |

| Zhou et al[14] | 52 | 63 | 46.30 ± 9.00 | 600 | 0.5 | 48 | 12, 24, 36, 48 | ACD | - | |

| Xu et al[15] | 30 | 30 | 32.70 ± 10.60 | 33.60 ± 8.80 | 600 | 0.5 | 24 | 12, 24, 48 | ABCDF | 1000 |

| Ye et al[16] | 46 | 46 | 32.20 | 600 | 0.5 | 48 | 12, 24, 48 | ABCDE | 100 | |

| Zhang et al[17] | 75 | 65 | 31.93 ± 7.96 | 600 | 0.5 | 72 | 8 ,12, 24, 52, 72 | ABDEF | 500 | |

| Liu[18] | 20 | 20 | 33.50 | 600 | 0.5 | 48 | 4, 12, 24, 48 | ABCDF | 1000 | |

| Zhao et al[19] | 42 | 39 | 33.56 ± 10.25 | 600 | 0.5 | 60 | 8, 12, 24, 48, 60 | ABD | 1000 | |

| Shi et al[20] | 40 | 40 | 30.50 ± 7.11 | 31.50 ± 7.95 | 600 | 0.5 | 24 | 12, 24 | ABCD | 500 |

| Yu et al[21] | 92 | 85 | 600 | 0.5 | 48 | 4, 8, 12, 24, 48 | ACD | 500 | ||

| Huang et al[22] | 90 | 90 | 28.80 ± 9.80 | 600 | 0.5 | 52 | 52 | ABCDE | 500 | |

| Ding et al[23] | 30 | 30 | 37.20 ± 7.96 | 36.10 ± 7.12 | 600 | 0.5 | 48 | 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, 48 | ABCDEF | 1000 |

| Zheng et al[24] | 65 | 66 | 31.60 ± 8.70 | 33.50 ± 9.10 | 600 | 0.5 | 24 | 12, 24 | AFCDF | 500 |

The following exclusion criteria were used: (1) Nonrandomized controlled trials (NRCTs); (2) Insufficient analytical information regarding treatment schedule, follow-up, and outcomes; (3) Patients receiving interferon, nucleosides or nucleotides for CHB within 6 mo; (4) Patients coinfected with hepatitis A, C, D and E virus, cytomegalovirus, or human immunodeficiency virus; (5) Patients with liver failure, HCC, and liver-related complications caused by alcoholism, autoimmune disease, and cholestasis; and (6) Pregnant and breastfeeding patients.

Data extraction was assessed independently by two reviewers (Song LY and Zhang SR). Discrepancies were solved through discussions between the reviewers or by a third person. Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.2 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, United Kingdom) was used to assess risk of bias (adequate sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data addressed, free of selective reporting and free of other bias)[10]. Basic information obtained from each eligible trial included study design, patient characteristics, number of two groups, treatment duration and related study results. Data were reviewed to eliminate duplicate reports of the same trial.

We used Review Manager Software 5.0 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, United Kingdom) for the data analysis. For dichotomous data, we used relative risk (RR) as an effect measure, and reported its 95% CI. Meta-analysis was performed using either a fixed-effect or random-effect model, based on the absence or presence of significant heterogeneity.

Statistical heterogeneity between trials was evaluated by χ2 and I2 analysis. The fixed-effect method was used in the absence of statistically significant heterogeneity (P≥ 0.1), and the random-effect method was used when the heterogeneity test was statistically significant (P < 0.1). P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Subgroup analysis was performed to examine the association between pre-specified characteristics (treatment duration) and the therapeutic effect, sensitivity analysis was made to estimate result stability, and funnel plots were used to assess publication bias if more than five trials were included[11].

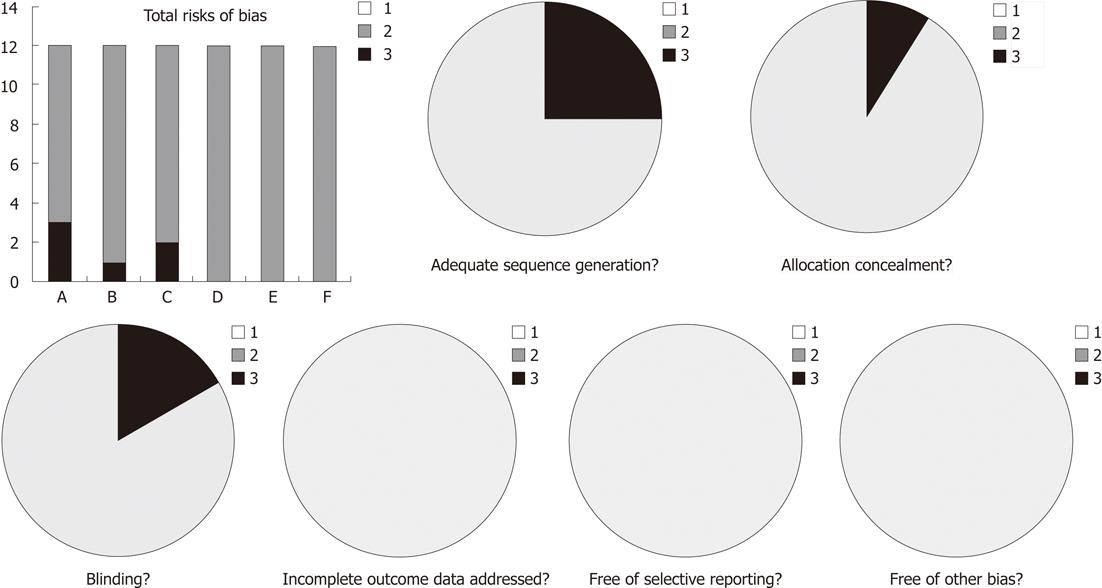

We initially identified 1165 abstracts, and after evaluating the full texts, we included 13 trials (12 in Chinese and one in English)[12-24] based on the pre-specified criteria. A total of 3925 patients were included: 1987 treated with LDT and 1938 treated with ETV. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 13 trials. All these studies showed baseline comparability, 9 of them reported the baseline of two groups in detail[13-15,17,19,20,22-24], the other 4 presented no significant differences in gender, age and duration of treatment between the two groups[12,16,18,21]. Three described the methods of randomization in detail[13,14,24], nine reported randomization, but did not describe the method of randomization in detail[12,15,17-23], one reported allocation concealment[24] and two presented blinding method[22,24]. None of the trials referred to incomplete outcome data addressed, free of selective reporting, and free of other bias. Various risks of bias in the 13 trials. In addition, none of the trials reported mortality, life quality and liver cancer incidence are shown in Figure 1.

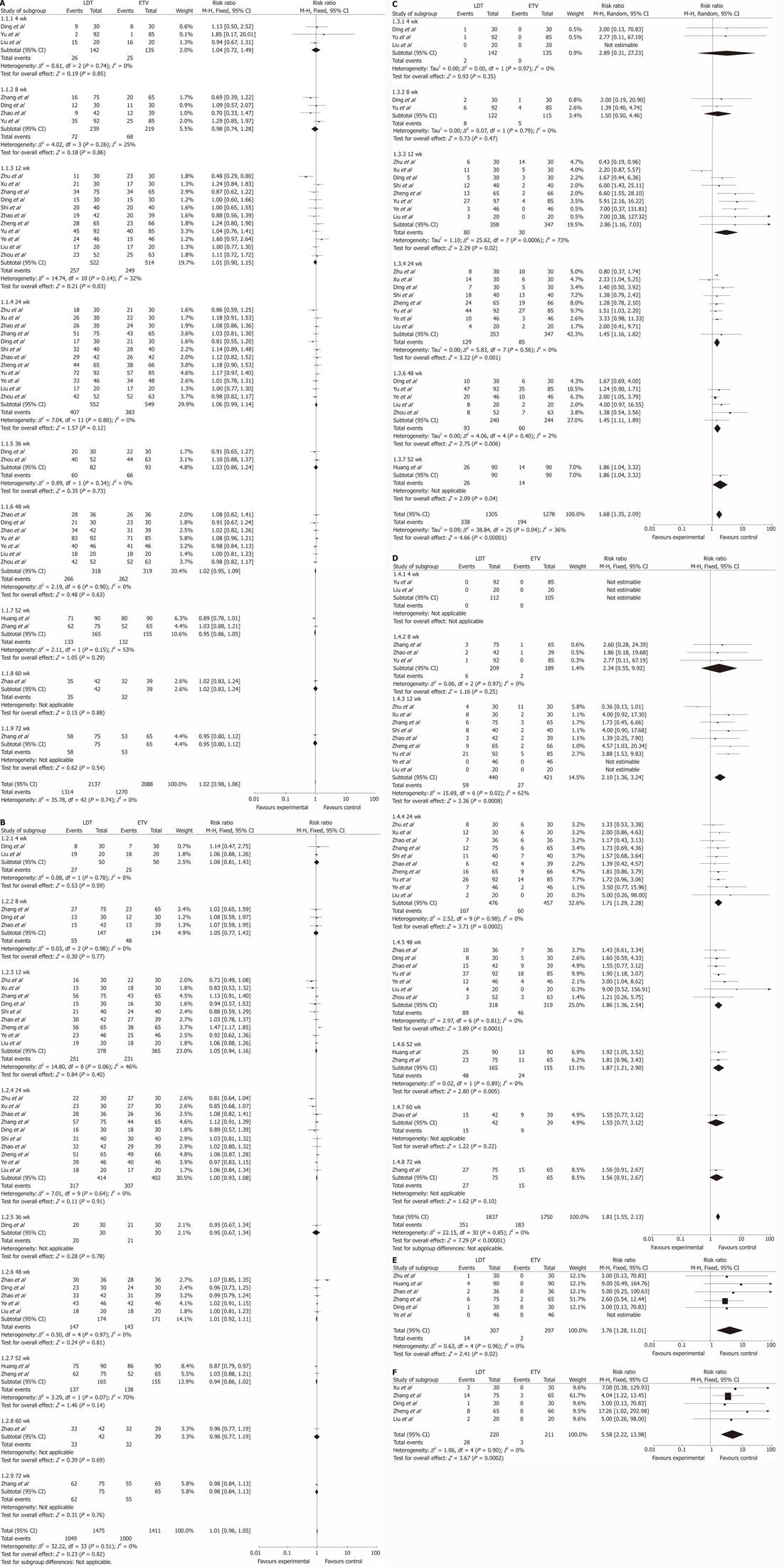

All the trials reported the rate of HBV DNA undetectability. χ2 and I2 analyses showed no heterogeneity (χ2 = 35.37, P = 0.74, I2 = 0%); therefore, we used the fixed-effect method to analyze the data. The results showed that in various treatment durations of 4 wk, 8 wk, 12 wk, 24 wk, 36 wk, 48 wk, 52 wk, 60 wk and 72 wk, there were no statistical differences in the rate of HBV DNA undetectability between the two groups (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.72, 1.49, P = 0.85; RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.74, 1.28, P = 0.86; RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.89, 1.15, P = 0.83; RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.99, 1.14, P = 0.12; RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.86, 1.37, P = 1.24; RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.95, 1.09, P = 0.63; RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.86, 1.05, P = 0.29; RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.83, 1.24, P = 0.88; and RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.80, 1.12, P = 0.54 ) (Figure 2A).

Eleven trials reported the rate of ALT normalization[12,13,15-20,22-24]. χ2 and I2 analysis showed no heterogeneity (χ2 = 32.22, P = 0.51, I2 = 0%). At various treatment durations of 4 wk, 8 wk, 12 wk, 24 wk, 36 wk, 48 wk, 52 wk, 60 wk and 72 wk, there were no statistical differences in the rate of ALT normalization between the two groups (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.81, 1.43, P = 0.59; RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.77, 1.43, P = 0.77; RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.94, 1.16, P = 0.40; RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.93, 1.08, P = 0.91; RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.67, 1.34, P = 0.78; RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.92, 1.11, P = 1.08; RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.86, 1.02, P = 0.14; RR 0.96, 95%CI 0.77, 1.19, P = 0.69; and RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.84, 1.13, P = 0.76) ( Figure 2B).

Ten trials reported the rate of HBeAg loss[13-16,18,20-24]. χ2 and I2 analyses found no heterogeneity (χ2 = 38.84, P = 0.04, I2 = 36%). At 4 wk and 8 wk of the treatment, no statistical differences in the rate of HBeAg loss were observed between the two groups (RR 2.89, 95% CI 0.31, 27.23, P = 0.35; and RR 1.50, 95% CI 0.50, 4.46, P = 0.47). At 12 wk, 24 wk, 48 wk and 52 wk, the rate of HBeAg loss was higher in the LDT group than in the ETV group, and the difference between two groups was statistically significant (RR 2.28, 95% CI 1.16, 7.03, P = 0.02; RR 1.45, 95% CI 1.16, 1.82, P = 0.001; RR 1.45, 95% CI 1.11, 1.89, P = 0.006; RR 1.86, 95% CI 1.04, 3.32, P = 0.04) (Figure 2C).

All the trials reported the rate of HBeAg seroconversion. χ2 and I2 analyses showed no heterogeneity (χ2 = 22.15, P = 0.85, I2 = 0%). At 4 wk, 8 wk, 60 wk and 72 wk of the treatment, the rate of HBeAg seroconversion in the two groups was similar, and no statistical significances were observed (RR 2.34, 95% CI 0.55, 9.92, P = 0.25; RR 1.55, 95% CI 0.77, 3.12, P = 0.22; RR 1.56, 95% CI 0.91, 2.67, P = 0.1). However, at 12 wk, 24 wk, 48 wk and 52 wk, the rate of HBeAg loss was higher in the LDT group than in the ETV group, with statistically significant difference between two groups (RR 2.1, 95% CI 1.36, 3.24, P = 0.0008; RR 1.71, 95% CI 1.29, 2.28, P = 0.0002; RR 1.86, 95% CI 1.36, 2.54, P < 0.0001; RR 1.87, 95% CI 1.21, 2.90, P = 0.005) (Figure 2D).

Six trials reported drug-resistance[12,13,16,17,22,23]. χ2 and I2 analyses showed no heterogeneity (χ2 = 0.63, P = 0.96, I2 = 0%). The rate of drug-resistance was higher in the LDT group than in the ETV group, and the difference between two groups was statistically significant (RR = 3.76, 95% CI 1.28, 11.01, P = 0.02) (Figure 2E).

Ten trials reported on the adverse reactions[12-18,20,23,24]. No severe adverse reactions were observed in both groups. Common adverse reactions in the two groups included influenza-like symptoms such as fever, headache, fatigue, muscular stiffness, gastrointestinal upset such as nausea and diarrhea, alopecia and rash. Five of the trials reported the rate of increased creatine kinase (CK)[15,17,18,23,24]. χ2 and I2 analyses showed no heterogeneity (χ2 = 1.06, P = 0.94, I2 = 0%). The rate of increased CK was higher in the LDT group than in the ETV group, the difference being statistically significant (RR 5.58, 95% CI 2.22, 13.98, P = 0.0002). But the increased CK recovered without any intervention, and did not influence the anti-HBV treatment ( Figure 2F).

Meta-analysis was performed based on the rate of HBeAg seroconversion, using the fixed-effect model, and the minimum sample size trials were excluded[18]. Odds ratio (OR) of all sensitivity analyses was higher than 1 and statistically significant (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

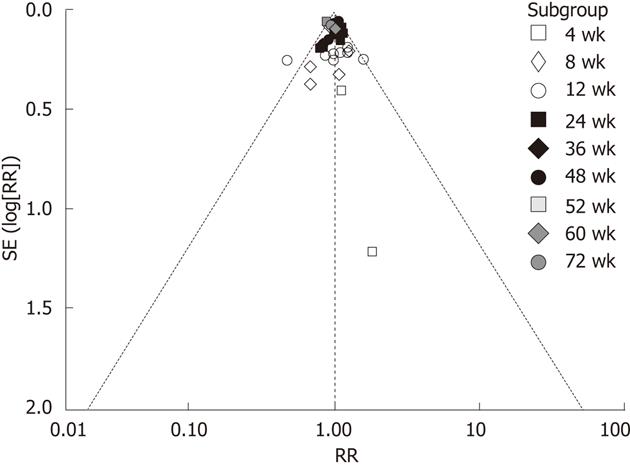

Funnel plots were performed based on the rate of HBV DNA undetectability. The results showed that funnel plots were symmetric and suggested that there was no publication bias (Figure 3).

The RCTs comparing LDT with ETV for patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B were included, and meta-analyses on virology, serology, biochemical responses, drug-resistance and adverse reactions were performed to examine the association between pre-specified characteristics (treatment duration) and the therapeutic effect of the two drugs.

HBV DNA level is a primary prognostic marker for the treatment of patients with CHB[25,26]. The early and sustained suppression of HBV DNA replication is associated with improved long-term rates of virological, serological and biochemical responses. Rapidly and effectively suppressing HBV DNA replication can decrease the incidence of liver cirrhosis (LC), HCC and drug-resistance[27,28]. The results of the meta-analysis showed that in various treatment durations (4 wk, 8 wk, 12 wk, 24 wk, 36 wk, 48 wk, 52 wk, 60 wk and 72 wk), there were no statistical differences in the rate of HBV DNA undetectability between the two groups. This suggested that both LDT and ETV have rapid and effective anti-viral activity and the result is similar with a large sample size study[29]. In addition, there was also no significant difference in the rate of ALT normalization between the two drugs.

HBeAg is a protein expressed by pre-C gene. HBeAg loss occurs with the rise of immunomodulatory effect which can suppress HBV DNA replication. HBeAg seroconversion has been established as a key marker of treatment response and is associated with improved clinical outcomes. It is one of the significant withdrawal standards for HBeAg-positive patients and suggests that patients can obtain sustained immune response[30]. The results of the meta-analysis showed that at 4 wk and 8 wk of the treatment, the rates of HBeAg loss and HBeAg seroconversion were similar, with no statistical difference between the two groups, while at 12 wk, 24 wk, 48 wk and 52 wk, the rate was higher in the LDT group than in the ETV group, the difference being statistically significant. At 60 wk and 72 wk, there was no significant difference in the rate of HBeAg seroconversion between the two groups. These results suggested that the rates of HBeAg loss and HBeAg seroconversion in the short-term and medium-term treatment were higher in the LDT group than in the ETV group. So LDT can be used as a primary drug for HBeAg-positive patients. However, its long-term efficacy needs to be further explored.

The higher rate of HBeAg seroconversion during LDT treatment might be associated with the potential immunomodulatory effect of LDT. CHB is a viral as well as an immunological disease. Specific immune function is impaired in the patients with CHB. Many studies suggested that LDT promoted T-helper 1 cytokine and CD4+/CD8+ cell production, but only downregulated programmed death ligand 1, regulatory T cell and T-helper 2 cytokine production[31-33]. These immunomodulatory effects increase the rate of HBeAg seroconversion.

ETV has a high genetic barrier to resistance[34-36]. The meta-analysis (Figure 2E) showed that the rate of drug-resistance was higher in the LDT group (4.69%) than in the ETV group (0.75%), the difference being statistically significant between the two groups. ETV has a lower drug-resistance than LDT and it is preferred for long-term anti-HBV activity.

The meta-analysis (Figure 2F) showed no severe adverse reactions in the two groups. Although the rate of increased CK in the LDT group was higher than in the ETV group, CK can recover without any intervention, and does not influence the anti-HBV treatment. These results suggest that both LDT and ETV are safe and well tolerated.

Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection is a major health problem affecting over 350 million people worldwide. CHB can lead to a number of life-threatening conditions such as liver failure, liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Recent studies have shown that telbivudine (LDT) and entacavir (ETV) are the strongest nucleoside analogues in the treatment of CHB. But there are few systematic reviews about the comparison of LDT and ETV.

LDT is an orally bioavailable L-nucleoside. It can rapidly and effectively suppress HBV DNA replication, but it has a higher drug-resistance. ETV is a new generation nucleoside analogues. It has the advantage of a higher rate of HBV DNA suppression, low drug-resistance and high safety, especially in lamivudine-resisitant CHB patients. But the rate of hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) loss and HBeAg seroconversion was very low, which is difficult to meet the withdrawal standards.

There are few systematic reviews about the efficacy of LDT and ETV in the CHB treatment. The authors conducted a meta-analysis of the included randomized controlled trials using the Cochrane methodology and explored the efficacy of LDT and ETV for clinical treatment of HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B .

The results of this meta-analysis suggest that LDT and ETV have similar virological and biomedical response, and both are safe and well tolerated. However, LDT has better serological response and higher rate of drug-resistance.

This study reviewed 13 trials comparing the effects of telbivudine and entecavir for patients with chronic HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B infection. Based on their analyses, the authors conclude that LDT and ETV exert an effective antiviral effect on HBV. Regarding the undetectability and ALT normalization, there was no big difference between the two drugs. The analysis was carefully performed, and the results were clearly presented and summarized, which provided valuable advice for clinical treatment of CHB.

Peer reviewers: Yukihiro Shimizu, MD, PhD, Kyoto Katsura Hospital, 17 Yamada-Hirao, Nishikyo, Kyoto 615-8256, Japan; Dr. Bernardo Frider, MD, Professor, Head of Department of Medicine and Hepatology, Department of Hepatology, Hospital General de Agudos Cosme Argerich, Alte Brown 240, 1155 Buenos Aires, Argentina; Dr. Eberhard Hildt, Professor, Molecular Virology-NG1, Robert Koch InstituteNordufer 20, D-13353 Berlin, Germany

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Lu YJ

| 1. | Cao GW. Clinical relevance and public health significance of hepatitis B virus genomic variations. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5761-5769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wright TL. Introduction to chronic hepatitis B infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101 Suppl 1:S1-S6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zoulim F, Locarnini S. Hepatitis B virus resistance to nucleos(t)ide analogues. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1593-1608.e1-e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 517] [Cited by in RCA: 550] [Article Influence: 32.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wursthorn K, Lutgehetmann M, Dandri M, Volz T, Buggisch P, Zollner B, Longerich T, Schirmacher P, Metzler F, Zankel M. Peginterferon alpha-2b plus adefovir induce strong cccDNA decline and HBsAg reduction in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2006;44:675-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 342] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sheng YJ, Liu JY, Tong SW, Hu HD, Zhang DZ, Hu P, Ren H. Lamivudine plus adefovir combination therapy versus entecavir monotherapy for lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Virol J. 2011;8:393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lai CL, Gane E, Liaw YF, Hsu CW, Thongsawat S, Wang Y, Chen Y, Heathcote EJ, Rasenack J, Bzowej N. Telbivudine versus lamivudine in patients with chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2576-2588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 607] [Cited by in RCA: 602] [Article Influence: 31.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chang TT, Gish RG, Hadziyannis SJ, Cianciara J, Rizzetto M, Schiff ER, Pastore G, Bacon BR, Poynard T, Joshi S. A dose-ranging study of the efficacy and tolerability of entecavir in Lamivudine-refractory chronic hepatitis B patients. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1198-1209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Chinese Society of Hepatology, Society of Infctious Diseases. China guidelines for HBV management. Zhonghua Ganzangbing Zazhi. 2011;19:13-24. |

| 10. | Higgins JPT, Green S, Altman DG. Chapter 8. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: Cochrane Book Series. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons Ltd. 2008; . |

| 11. | Wang JL, Wang B. Clinical epidemiology: Clinical scientific research and design, measure and evaluation. Shanghai: Shanghai Scientific and Technical Publishers 2009; 1-536. |

| 12. | Zhao JZ. A comparison of telbivudine and entecavir for treatment of the patients with chronic hepatitis B. Zhongguo Baojian. 2009;17:846-847. |

| 13. | Zhu FY. Twenty-four week results of entecavir versus telbivudine treatment in patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Linchuang Junyi Zazhi. 2011;39:14-16. |

| 14. | Zhou Y, Li JP, Guan YJ. Study on the efficacy between entecavir and telbivudine in treating chronic hepatitis B patients. Zhongguo Yiyuan Yaoxue Zazhi. 2010;30:2004-2007. |

| 15. | Xu HX, Yu YX, Zhang MX, Wu YP, Liu XX, Chen Y. Application of telbivudine and entecavir in the treatment of patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Shiyong Ganzangbing Zazhi. 2011;14:265-267. |

| 16. | Ye WF, Chen ZT, Wu JC, Gan JH. Short-term efficacy of telbivudine in patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Suzhou Daxue Xuebao. 2009;29:343-344. |

| 17. | Zhang JZ, Yang BY, Chen K, Zhang CL, Yao XA, Zhao LZ, Tan YZ. Efficacy of telbivudine versus that of entecavir for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Zhonghua Ganzangbing Zazhi. 2010;26:2609-2611. |

| 18. | Liu W. Fourty-eight wk results of entecavir and telbivudine treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Zhongxi yi Jiehe Ganbing Zazhi. 2010;20:366-367. |

| 19. | Zhao LF, Jiang Y, Wang Y. Efficacy of telbivudine versus that of entecavir for HBeAg -positive chronic hepatitis B. Shisong Yixue Zazhi. 2011;18:71-72. |

| 20. | Shi KQ, Zhang DZ, Guo SH, He H, Wang ZY, Shi XF, Zeng WQ, Ren H. Short-term results of teibivudine versus entecavir treatments in HBeAg- positive chronic hepatitis B patients in China. Yaowu Yu Linchuang. 2008;16:641-645. |

| 21. | Yu P, Huang LH, Wang JH. Efficacy of telbivudine and entecavir treatment in patients with primary treated chronic hepatitis B. Zhongxiyi Jiehe Ganbing Zazhi. 2010;20:117-118. |

| 22. | Huang J, Chen XP, Chen WL, Chen R, Ma XJ, Luo XD. Studyon the efficacy and HBeAg seroconversion related factors of telbivudine and entecavir therapy in HBeAg positive chronic hepatitis B pafients. Zhonghua Ganzangbing Zazhi. 2011;19:178-181. |

| 23. | Ding K, Chen SJ. Study on the Comparison between LdT’S and ETV’S Effect of Resisting HBV Virus and the Adverse Reaction. Available from: http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-YXLT201220007.htm. |

| 24. | Zheng MH, Shi KQ, Dai ZJ, Ye C, Chen YP. A 24-week, parallel-group, open-label, randomized clinical trial comparing the early antiviral efficacy of telbivudine and entecavir in the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B virus infection in adult Chinese patients. Clin Ther. 2010;32:649-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Keeffe EB, Dieterich DT, Han SH, Jacobson IM, Martin P, Schiff ER, Tobias H, Wright TL. A treatment algorithm for the management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: an update. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:936-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sherman M. Predicting survival in hepatitis B. Gut. 2005;54:1521-1523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Chen CJ, Yang HI, Su J, Jen CL, You SL, Lu SN, Huang GT, Iloeje UH. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA. 2006;295:65-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2309] [Cited by in RCA: 2393] [Article Influence: 119.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Keeffe EB, Zeuzem S, Koff RS, Dieterich DT, Esteban-Mur R, Gane EJ, Jacobson IM, Lim SG, Naoumov N, Marcellin P. Report of an international workshop: Roadmap for management of patients receiving oral therapy for chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:890-897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Suh DJ, Um SH, Herrmann E, Kim JH, Lee YS, Lee HJ, Lee MS, Lee YJ, Bao W, Lopez P. Early viral kinetics of telbivudine and entecavir: results of a 12-week randomized exploratory study with patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:1242-1247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tsai MC, Lee CM, Chiu KW, Hung CH, Tung WC, Chen CH, Tseng PL, Chang KC, Wang JH, Lu SN. A comparison of telbivudine and entecavir for chronic hepatitis B in real-world clinical practice. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:696-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Nan XP, Zhang Y, Yu HT, Sun RL, Peng MJ, Li Y, Su WJ, Lian JQ, Wang JP, Bai XF. Inhibition of viral replication downregulates CD4(+)CD25(high) regulatory T cells and programmed death-ligand 1 in chronic hepatitis B. Viral Immunol. 2012;25:21-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Chen Y, Li X, Ye B, Yang X, Wu W, Chen B, Pan X, Cao H, Li L. Effect of telbivudine therapy on the cellular immune response in chronic hepatitis B. Antiviral Res. 2011;91:23-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Zheng Y, Huang Z, Chen X, Tian Y, Tang J, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Zhou J, Mao Q, Ni B. Effects of telbivudine treatment on the circulating CD4⁺ T-cell subpopulations in chronic hepatitis B patients. Mediators Inflamm. 2012;2012:789859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Sherman M, Yurdaydin C, Sollano J, Silva M, Liaw YF, Cianciara J, Boron-Kaczmarska A, Martin P, Goodman Z, Colonno R. Entecavir for treatment of lamivudine-refractory, HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:2039-2049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 328] [Cited by in RCA: 312] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Tenney DJ, Rose RE, Baldick CJ, Pokornowski KA, Eggers BJ, Fang J, Wichroski MJ, Xu D, Yang J, Wilber RB. Long-term monitoring shows hepatitis B virus resistance to entecavir in nucleoside-naïve patients is rare through 5 years of therapy. Hepatology. 2009;49:1503-1514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 615] [Cited by in RCA: 636] [Article Influence: 37.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Colonno RJ, Rose R, Baldick CJ, Levine S, Pokornowski K, Yu CF, Walsh A, Fang J, Hsu M, Mazzucco C. Entecavir resistance is rare in nucleoside naïve patients with hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2006;44:1656-1665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 279] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |