Published online Nov 21, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i43.6255

Revised: August 21, 2012

Accepted: September 12, 2012

Published online: November 21, 2012

AIM: To study the coincidence of celiac disease, we tested its serological markers in patients with various liver diseases.

METHODS: Large-scale screening of serum antibodies against tissue transglutaminase (tTG), and deamidated gliadin using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and serum antibodies against endomysium using immunohistochemistry, in patients with various liver diseases (n = 962) and patients who underwent liver transplantation (OLTx, n = 523) was performed. The expression of tTG in liver tissue samples of patients simultaneously suffering from celiac disease and from various liver diseases using immunohistochemistry was carried out. The final diagnosis of celiac disease was confirmed by histological analysis of small-intestinal biopsy.

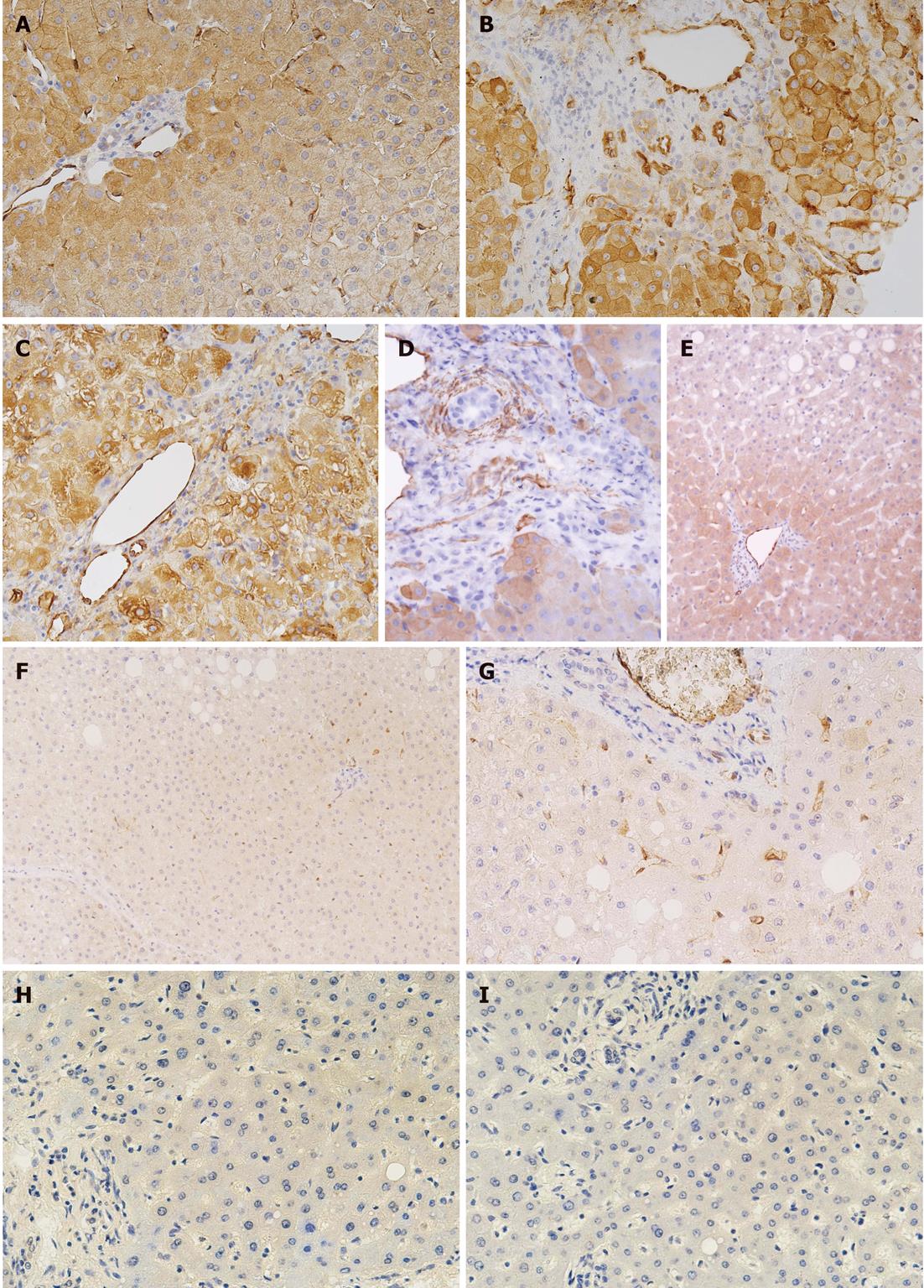

RESULTS: We found that 29 of 962 patients (3%) with liver diseases and 5 of 523 patients (0.8%) who underwent OLTx were seropositive for IgA and IgG anti-tTG antibodies. However, celiac disease was biopsy-diagnosed in 16 patients: 4 with autoimmune hepatitis type I, 3 with Wilson's disease, 3 with celiac hepatitis, 2 with primary sclerosing cholangitis, 1 with primary biliary cirrhosis, 1 with Budd-Chiari syndrome, 1 with toxic hepatitis, and 1 with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Unexpectedly, the highest prevalence of celiac disease was found in patients with Wilson's disease (9.7%), with which it is only rarely associated. On the other hand, no OLTx patients were diagnosed with celiac disease in our study. A pilot study of the expression of tTG in liver tissue using immunohistochemistry documented the overexpression of this molecule in endothelial cells and periportal hepatocytes of patients simultaneously suffering from celiac disease and toxic hepatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis or autoimmune hepatitis type I.

CONCLUSION: We suggest that screening for celiac disease may be beneficial not only in patients with associated liver diseases, but also in patients with Wilson's disease.

- Citation: Drastich P, Honsová E, Lodererová A, Jarešová M, Pekáriková A, Hoffmanová I, Tučková L, Tlaskalová-Hogenová H, Špičák J, Sánchez D. Celiac disease markers in patients with liver diseases: A single center large scale screening study. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(43): 6255-6262

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i43/6255.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i43.6255

Celiac disease (CLD) is a frequent, lifelong, primarily small intestinal enteropathy with an incidence of more than 1:250 which is induced in genetically susceptible individuals after ingestion of wheat gluten. The duodenal and jejunal mucosa of patients with active CLD is infiltrated by leukocytes and structurally remodeled. Villous flattening and crypt hyperplasia develop in the mucosa of these patients and cause malabsorption syndrome, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and weight loss. However, these symptoms predominate in pediatric patients (accompanied by growth retardation), whereas latent and silent forms of CLD occur more often in adult patients[1-3].

Interestingly, a growing proportion of new cases of CLD are being diagnosed in adults and in patients with extraintestinal manifestations. CLD may affect several organs including kidney, skin, heart, and the nervous, endocrine and reproductive systems, however, liver injury is one of the most frequent extraintestinal manifestations of the disease. Although the spectrum of liver manifestations associated with CLD is particularly wide, two main forms of liver damage, namely cryptogenic and autoimmune, appear to be strictly related to this disease. The most frequent finding documenting liver damage in CLD is a cryptogenic hypertransaminasemia, observed in approximately 15%-55% of untreated patients, as an expression of mild liver dysfunction with a histological picture of nonspecific reactive hepatitis (“celiac hepatitis”). However, in a few cases a more severe liver injury, characterized by a cryptogenic chronic hepatitis or liver cirrhosis requiring liver transplantation, is present. A close association is known to exist between CLD and autoimmune liver diseases such as primary biliary cirrhosis with a prevalence of 3%-7%, autoimmune hepatitis (3%-6%), and primary sclerosing cholangitis (2%-3%). This is probably related to an association between CLD and the human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DQ heterodimer DQA1/0501/DQB1/0201 on antigen-presenting cells. In CLD, the number of gliadin-specific HLA-DQ2- or HLA-DR4-restricted T-lymphocytes expands and high titers of antibodies against gliadin and various autologous antigens are generated, which can affect the functions of many organs[3-7].

The therapy of CLD is still based on the withdrawal of gluten and its related proteins from the diet of patients [gluten-free diet (GFD)]. After 6-12 mo on a GFD, most CLD patients experience a clinical improvement accompanied by restoration of the intestinal mucosa and a reduction in the number of gliadin and autoantigen-restricted lymphocytes. The serum concentrations of anti-gliadin antibodies and antibodies against autologous antigens are also reduced. Interestingly, mild liver dysfunction with a histological picture of nonspecific reactive hepatitis (celiac hepatitis) may improve after institution of a GFD[8-11]. Although the withdrawal of gluten from the patients’ diet improves celiac hepatitis, its influence on autoimmune hepatitis is controversial and in childhood, in which the diagnosis and the introduction of GFD are not usually delayed, it seems ineffective. However, the diet may reduce the risk of CLD complications and development of the most severe refractory CLD[12-15].

The diagnosis of CLD is based on the histological analysis of a duodenal/jejunal biopsy and the testing of serum antibodies against gliadin and autoantibodies against endomysium or tissue transglutaminase (tTG).

This study focused on serological screening for CLD in patients with liver diseases and those who underwent liver transplantation, i.e., patients with a known higher risk of developing CLD. Moreover, we also analyzed the tissue expression and distribution of tTG in the liver of patients with various liver diseases, especially those simultaneously suffering from CLD and compared these to morphologically unaltered liver tissue.

The study enrolled patients treated in the Department of Hepatogastroenterology, Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Prague, in 2009-2010. Sera from a total of 1485 patients were tested. The tested cohorts included 962 patients with diagnosed liver diseases (mean age 55 years, range: 21-76 years) and 523 patients (mean age 49 years, range: 18-66 years) who underwent liver transplantation during 1994-2010 as a consequence of end stage of liver disease. Table 1 summarizes the baseline clinical characteristics of the patients and healthy controls included in our study. The cohort of healthy controls (n = 300, mean age 23 years, range: 18-45 years) was selected from the Institute of Hematology and Blood Transfusion (Prague, Czech Republic).

| Disease | Diagnosis | n (M/F) |

| Liver disease | Alcoholic liver cirrhosis | 152 (94/58) |

| Autoimmune hepatitis type I | 77 (27/50) | |

| Viral hepatitis B | 117 (67/50) | |

| Viral hepatitis C | 147 (82/65) | |

| Wilson’s disease | 31 (13/18) | |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 32 (4/28) | |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 59 (40/19) | |

| Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis | 23 (10/12) | |

| Liver steatosis | 132 (77/55) | |

| Budd-Chiari syndrome | 14 (5/9) | |

| Polycystic liver | 10 (1/9) | |

| Others1 | 168 (74/94) | |

| OLTx | Alcoholic liver cirrhosis | 164 (131/33) |

| Autoimmune hepatitis type I | 33 (11/22) | |

| Viral hepatitis B | 33 (20/13) | |

| Viral hepatitis C | 79 (56/23) | |

| Wilson’s disease | 29 (12/17) | |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 40 (5/35) | |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 64 (47/17) | |

| Cryptogenic liver cirrhosis | 28 (16/12) | |

| Budd-Chiari syndrome | 6 (2/4) | |

| Polycystic liver | 14 (3/11) | |

| Others2 | 33 (16/17) |

The diagnostic criteria for primary biliary cirrhosis included clinical symptoms, clinical chemistry, exclusion of infection with hepatitis viruses and evidence of anti-mitochondrial antibodies type M2. The diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis was based on the scoring system devised by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group and International Association for the Study of the Liver[16]. The main diagnostic criteria for alcoholic liver cirrhosis were the patient’s medical history, liver histology, and exclusion of other causes of liver cirrhosis. Diagnosis of Wilson’s disease was based on the recommendation of Kodama et al[17], and Budd-Chiari syndrome in accordance with the concept of Fox et al[18]. Patients who underwent liver transplantation were treated with standard immunosuppressive therapy following appropriate guidelines. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee.

Diagnostics and markers for screening of CLD: All serum samples were tested for immunoglobulin (Ig) A and IgG antibodies against tTG. Individuals seropositive for IgA or IgG anti-tTG antibodies were tested for IgA or IgG (in the case of patients with IgA immunodeficiency) isotypes of antibodies against deamidated gliadin (IgA and IgG) and anti-endomysium (IgA or IgG). The final diagnosis of CLD, in individuals seropositive for these IgA or IgG antibodies, was performed by duodenal/jejunal biopsy.

Serological assays used for CLD screening: All tests were performed in the immunological laboratory of the Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The BINDAZYME™ Anti-Tissue Transglutaminase EIA kit (the Binding Site, Birmingham, United Kingdom) and ORG 540A and ORG 540G Anti-Tissue-Transglutaminase ELISA kit (ORGENTEC Diagnostika GmbH, Mainz, Germany) were simultaneously used to test for IgA or IgG anti-tTG antibodies, IgA or IgG anti-gliadin antibodies were tested using QUANTA Lite Gliadin IgA or QUANTA Lite Gliadin IgG (INOVA Diagnostic Inc., San Diego, CA, United States), and by ELISA kits ANTI GLIADIN MGP IgA and ANTI GLIADIN MGP IgG (Binding Site). The results of the serological testing were expressed as a percentage of antibody-positive patients within individual groups. To exclude immunoglobulin deficiency, total IgA and IgG blood levels were analyzed using a routine method in all tested patients.

Anti-endomysial antibodies were routinely tested by an indirect immunofluorescence method using human umbilical cord tissue cryostat sections. The test serum samples were diluted 1:20 and 1:50. Slides were examined using a Nikon Eclipse E600 immunofluorescence microscope (Nikon, Japan). A positive result was recorded if the connective tissue surrounding the muscle cells was brightly fluorescent, forming a honeycomb pattern.

Analysis of tTG expression in liver tissue: The expression and distribution of tTG in the liver biopsy samples from 25 patients were analyzed and compared. Eight patients suffered from CLD simultaneously with liver diseases (2 patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis, 1 with autoimmune hepatitis type I, 1 with toxic hepatitis, 1 with Budd-Chiari syndrome, 3 with celiac hepatitis), 8 patients with liver diseases (3 with primary sclerosing cholangitis, 2 with autoimmune hepatitis type I, 1 patient with steatosis, 1 with Budd-Chiari syndrome and 1 patient with primary biliary cirrhosis), and 9 patients with liver metastasis from colorectal carcinoma where tTG expression was analyzed on histologically confirmed unaltered liver tissue at least 3 cm away from the metastasis. The patients with liver disease simultaneously suffering from CLD were seropositive for IgA antibodies against tTG, endomysium and gliadin. MARSH IIIb-c stage of jejunal mucosa was present in these patients. On the other hand, the patients suffering from liver diseases, but not from CLD, included in the analysis of tTG expression in liver were seronegative for all of the mentioned antibodies. Therefore, there was no reason to perform a small intestinal biopsy in these patients.

The tTG detection in liver tissue was performed using the immunoperoxidase staining technique, N-Histofine® Simple Stain MAX PO (MULTI, Nichirei, Japan). Detection was performed on 4 μm thick paraffin sections. Tissue sections were deparaffinated, rehydrated, and antigen retrieval was performed using heat-induced epitope restoration in an EDTA buffer of pH 8.0. Endogenous peroxidase was inactivated with 0.3% H2O2 in 70% methanol for 30 min at room temperature. The sections were then incubated for 2 h with anti-tTG antibody CUB 7402 (Acris, Germany), diluted at 1:1200 in antibody diluent, Dako Real (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). After a washing step, Histofine Simple Stain Max PO was added for 30 min. Tissue staining was visualized with a 3,3'-diaminobenzidine substrate chromogen solution (Dako). Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted. A negative control was included by omitting the anti-tTG antibody. An isotype control was included using a nonspecific mouse IgG1 instead of specific anti-tTG antibody.

In our study, 29 of 962 adult patients with various liver diseases (3%) were seropositive for IgA anti-tTG antibodies. A summary of the data on seropositive patients is given in Table 2. Seropositivity for anti-tTG antibodies-detected by employing two different diagnostic kits-was found in five patients with autoimmune hepatitis type I, four patients with liver steatosis, four with Wilson’s disease, two with primary sclerosing cholangitis, two with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, and one each with polycystic liver disease, Budd-Chiari syndrome, primary biliary cirrhosis, toxic hepatitis, and hepatitis B. Seven patients with mild liver test abnormalities were also seropositive for anti-tTG.

| IgA anti-tTG seropositivity | Diagnosis | M/F | n (%) |

| Liver disease | Wilson’s disease | 1/3 | 4 (12.9) |

| Autoimmune hepatitis type I | 1/4 | 5 (6.5) | |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 0/1 | 1 (3.1) | |

| Budd-Chiari syndrome | 0/1 | 1 (7.1) | |

| Mild hepatic liver tests abnormalities | 5/2 | 7 (20) | |

| Liver steatosis | 3/1 | 4 (3.3) | |

| Viral hepatitis B | 1/0 | 1 (0.9) | |

| Toxic hepatitis | 1/0 | 1 (4.8) | |

| Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis | 0/2 | 2 (8.7) | |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 1/1 | 2 (3.4) | |

| Polycystic liver | 0/1 | 1 (10) | |

| OLTx | Wilson’s disease | 1/1 | 2 (6.9) |

| Autoimmune hepatitis type I | 0/2 | 2 (6.1) | |

| Alcoholic liver cirrhosis | 1/0 | 1 (0.6) |

Sixteen of 29 patients, i.e., those who were positive for IgA anti-tTG antibodies, were also seropositive for IgA anti-gliadin and anti-endomysial antibodies. This cohort included patients with autoimmune hepatitis type I (4), Wilson’s disease (3), celiac hepatitis (3, recruited from the group of anti-tTG seropositive patients with mild liver test abnormalities), primary sclerosing cholangitis (2), primary biliary cirrhosis (1), Budd-Chiari syndrome (1), toxic hepatitis (1), and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (1). Histological analysis of duodenal or jejunal specimens confirmed the diagnosis of CLD in these 16 patients according to European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition criteria. MARSH IIIa-c stages of gut mucosa were observed in all 16 patients. The clinical data of these newly diagnosed patients are summarized in Table 3. After 6 mo of adhesion to the GFD, all tested antibodies decreased to values occurring in healthy individuals and staging of mucosal lesions improved substantially (MARSH 0-I) in these patients. Four of these 16 patients (three with celiac hepatitis, one with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis) showed normalization of liver tests. However, no substantial clinical and laboratory improvements were observed in the other patients adequately treated for liver disease and adhering to a GFD.

| No. | Age | Gender | Diagnosis | Liver histology |

| 1 | 34 | F | PSC | Portal tracts with ductular reaction and minimal inflammation, features of chronic cholestasis |

| 2 | 37 | M | PSC | Florid ductular reaction with accompanying mild mixed inflammation and focal dark-brown granules of copper-associated protein (in orcein stain) in periportal hepatocytes |

| 3 | 33 | M | Wilson's d. | Macrovesicular steatosis, periportal fibrosis and periportal hepatocytes with glycogenated nuclei |

| 4 | 35 | F | Wilson's d. | Focal steatosis, periportal and septal fibrosis |

| 5 | 36 | F | Wilson's d. | Mild nonspecific hepatocellular injury with spotty hepatocyte necrosis and mononuclear portal |

| inflammatory infiltrate, scattered apoptotic bodies and mild steatosis | ||||

| 6 | 29 | M | AIH type I | Portal and lobular inflammation, periportal fibrosis |

| 7 | 33 | F | AIH type I | Portal and periportal inflammation, spotty necrosis |

| 8 | 33 | F | AIH type I | Chronic hepatitis pattern of injury with portal-based inflammation and fibrosis |

| 9 | 40 | F | AIH type I | Periportal interface activity and scattered hepatocyte necrosis |

| 10 | 35 | F | PBC | Bile duct injury with epithelioid granuloma, portal inflammation |

| 11 | 32 | M | Toxic hepatitis | Portal inflammation with scattered eosinophils, spotty necrosis |

| 12 | 50 | F | Budd-Chiari s. | Extensive centrilobular necrosis of hepatocytes |

| 13 | 22 | M | Celiac hepatitis | Non-specific reactive hepatitis with mild portal inflammation |

| 14 | 27 | M | Celiac hepatitis | Mild lobular inflammation with apoptotic bodies and hepatocyte necrosis |

| 15 | 50 | F | Celiac hepatitis | Mild periportal fibrosis with mild portal inflammation and focal interface activity |

| 16 | 40 | F | NASH | Ballooned hepatocytes, macrovesicular steatosis accentuated in zone 3 without significant liver injury |

Ten of the 16 newly diagnosed patients showed some non-specific symptoms of CLD (weight loss, diarrhea, abdominal pain), while 6 patients were asymptomatic for CLD.

Serum samples from the blood donors were negative for IgA anti-tTG antibodies.

Of the 523 patients who underwent liver transplantation, five (0.8%) were positive for IgA anti-tTG antibodies. A summary of the data on seropositive patients is given in Table 2. Anti-tTG antibody seropositivity occurred in 2 patients transplanted for autoimmune hepatitis type I, two for Wilson’s disease and one transplanted for alcoholic liver cirrhosis. However, none of these patients was seropositive for IgA anti-endomysial antibodies or for IgA and IgG anti-gliadin antibodies. CLD symptoms were not observed in five patients who were seropositive for IgA anti-tTG. For that reason, small intestinal biopsy was not performed in these patients.

In liver diseases, tTG is closely related with tissue repair, fibrogenesis and inflammation[19]. For this reason, we analyzed tTG expression in the liver tissue of twenty five patients simultaneously suffering from active CLD and liver disease, patients suffering from liver disease, but not from CLD, and patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma.

In this pilot study, we found overexpression of tTG in the liver tissue of patients suffering from liver diseases in contrast to morphologically unaltered tissues. However, individual variability in tTG expression in the liver tissue of these patients was detected. Despite this, the overexpression of tTG was predominantly localized in endothelial cells and periportal hepatocytes and was more pronounced in the liver tissue of all patients suffering simultaneously from both liver diseases and active CLD in contrast to patients suffering only from liver disease. Figure 1 shows more pronounced tTG staining in the liver specimens of patients simultaneously suffering from active CLD and primary sclerosing cholangitis, toxic hepatitis, and autoimmune hepatitis type I compared to patients suffering only from primary sclerosing cholangitis and steatosis.

CLD is frequently associated with various autoimmune liver diseases such as autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis, all of which may be indications for liver transplantation. On the other hand, a controversial association exists between hepatitis B and C virus and CLD. Chronic untreated CLD of long duration may also lead to liver damage severe enough to require liver transplantation[4,6,20-24]. Consistent with the above, reversal of hepatic failure has been described in CLD patients simultaneously suffering from liver disorders who followed a GFD[25]. On the other hand, GFD did not always lead to complete resolution of liver damage in all patients with CLD associated with liver disease[26-28].

This study on the occurrence of CLD and its serological markers in patients with various hepatic disorders and in those who underwent liver transplantation in the Czech Republic complements the serological screening for CLD in the general population (blood donors) and high-risk patients groups e.g., patients with osteoporosis, female infertility and some autoimmune diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome and patients with connective tissue disorders in the Czech population performed by Vanciková et al[29]. In the present study, we estimated, for the first time, the coincidence of CLD and liver diseases and the relationship between CLD and liver transplantation in the Czech population. Surprisingly, our results documented the highest incidence of CLD in patients with Wilson’s disease (9.7%), followed by autoimmune hepatitis (3.9%), primary biliary cirrhosis (3.0%), and primary sclerosing cholangitis (3.4%). While a higher incidence of CLD with primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis and autoimmune hepatitis has been well described[26,28], the association between CLD and Wilson’s disease is rare[30-32]. The coincidence of Wilson’s disease and CLD was high compared with the coincidence of CLD and osteoporosis (0.98%), female infertility (1.13%) and systemic lupus erythematosus (approximately 2.7%) in the Czech population[29]. Our findings of a higher incidence of CLD in adult patients could be associated with the underestimation of CLD diagnosis described in the elderly[33].

Despite the fact that Wilson’s disease, which is characterized by accumulation of copper in tissue, is rarely associated with CLD[30-32], it has been reported that copper metabolism is also impaired in CLD. In CLD patients, copper uptake from the gut is significantly reduced and levels of copper in urine are higher than in healthy individuals[31,32].

In our study, anti-tTG seropositivity in patients who underwent liver transplantation was lower than that described in previous studies[6]. A possible explanation for this is the exclusion from screening of 5 patients who underwent liver transplantation for primary sclerosing cholangitis (2 men, 39 years and 40 years), autoimmune hepatitis type I (woman, 25 years), viral hepatitis B (woman, 51 years) and viral hepatitis C (woman, 56 years), in whom CLD was diagnosed before the beginning of this study. All five patients who underwent liver transplantation and were seropositive for IgA anti-tTG antibodies were also seropositive for the IgG isotype of the antibodies, but seronegative for the remaining CLD markers - antibodies against deamidated gliadin and endomysium. The antibody levels, as well as histological changes in small intestine mucosa characteristic of CLD, could have been affected by immunosuppressive treatment complicating the diagnosis of CLD in those patients who underwent liver transplantation[34]. This could also be the reason for the difference in seropositivity between cohorts of patients suffering from liver disease and patients who underwent liver transplantation. The putative reason for the development of anti-tTG antibodies in patients who underwent liver transplantation could be overexpression of tTG in the graft during repair and healing processes. However, our findings concerning the expression of tTG in liver and induction of anti-tTG antibodies need further investigation. Nevertheless, the testing of CLD serological markers seems to be useful in patients considered for liver transplantation.

In conclusion, we suggest that screening for CLD may be beneficial not only in groups of patients with well-known associated diseases (autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis), but also in patients with Wilson’s disease, where the relationship to CLD has not been fully analyzed.

Celiac disease (CLD) is a frequent, lifelong, primarily small intestinal enteropathy with an incidence of more than 1:250 which is induced in genetically susceptible individuals after ingestion of wheat gluten. A growing proportion of new cases of CLD are being diagnosed in adults and in patients with extraintestinal manifestations. CLD may affect several organs including kidney, skin, heart, and the nervous, endocrine and reproductive systems, however, liver injury is one of the most frequent extraintestinal manifestations of the disease.

This study on the occurrence of CLD and its serological markers in patients with various hepatic disorders and in those who underwent liver transplantation in the Czech Republic complements the serological screening for CLD in the general population (blood donors) and high-risk patients groups.

The authors suggest that screening for CLD may be beneficial not only in groups of patients with well-known associated diseases (autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis), but also in patients with Wilson’s disease, where the relationship to CLD has not been fully analyzed.

Their findings on the expression of tissue transglutaminase (tTG) in liver and induction of anti-tTG antibodies need further investigation. Nevertheless, the testing of CLD serological markers seems to be useful in patients considered for liver transplantation.

The study is a large scale serological investigation on CLD in patients with liver disease. This study first time revealed a relation between Wilson’s disease and CLD, and overexpression of tTG in liver tissue.

| 1. | Lochman I, Martis P, Burlingame RW, Lochmanová A. Multiplex assays to diagnose celiac disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1109:330-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | McGowan KE, Lyon ME, Loken SD, Butzner JD. Celiac disease: are endomysial antibody test results being used appropriately? Clin Chem. 2007;53:1775-1781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rodrigo L, Fuentes D, Riestra S, Niño P, Alvarez N, López-Vázquez A, López-Larrea C. [Increased prevalence of celiac disease in first and second-grade relatives. A report of a family with 19 studied members]. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2007;99:149-155. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Volta U. Pathogenesis and clinical significance of liver injury in celiac disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2009;36:62-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Czaja AJ. Cryptogenic chronic hepatitis and its changing guise in adults. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:3421-3438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rubio-Tapia A, Murray JA. The liver in celiac disease. Hepatology. 2007;46:1650-1658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sifford M, Koch A, Lee E, Peña LR. Abnormal liver tests as an initial presentation of celiac disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:3016-3018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Freeman HJ, Chopra A, Clandinin MT, Thomson AB. Recent advances in celiac disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2259-2272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Marsh MN. Gluten, major histocompatibility complex, and the small intestine. A molecular and immunobiologic approach to the spectrum of gluten sensitivity (‘celiac sprue'). Gastroenterology. 1992;102:330-354. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Meresse B, Ripoche J, Heyman M, Cerf-Bensussan N. Celiac disease: from oral tolerance to intestinal inflammation, autoimmunity and lymphomagenesis. Mucosal Immunol. 2009;2:8-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lo Iacono O, Petta S, Venezia G, Di Marco V, Tarantino G, Barbaria F, Mineo C, De Lisi S, Almasio PL, Craxì A. Anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies in patients with abnormal liver tests: is it always coeliac disease? Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2472-2477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Leonardi S, Pavone P, Rotolo N, Spina M, La Rosa M. Autoimmune hepatitis associated with celiac disease in childhood: report of two cases. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:1324-1327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Al-toma A, Verbeek WH, Mulder CJ. The management of complicated celiac disease. Dig Dis. 2007;25:230-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tack GJ, Verbeek WH, Al-Toma A, Kuik DJ, Schreurs MW, Visser O, Mulder CJ. Evaluation of Cladribine treatment in refractory celiac disease type II. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:506-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Prasad KK, Sharma AK, Nain CK, Singh K. Commentary on: Are hepatitis B virus and celiac disease linked?: HBV and Celiac Disease. Hepat Mon. 2011;11:44-45. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Manns MP, Strassburg CP. Autoimmune hepatitis: clinical challenges. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1502-1517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kodama H, Fujisawa C, Bhadhprasit W. Inherited copper transport disorders: biochemical mechanisms, diagnosis, and treatment. Curr Drug Metab. 2012;13:237-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fox MA, Fox JA, Davies MH. Budd-Chiari syndrome--a review of the diagnosis and management. Acute Med. 2011;10:5-9. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Elli L, Bergamini CM, Bardella MT, Schuppan D. Transglutaminases in inflammation and fibrosis of the gastrointestinal tract and the liver. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:541-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Casswall TH, Papadogiannakis N, Ghazi S, Németh A. Severe liver damage associated with celiac disease: findings in six toddler-aged girls. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:452-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sánchez D, Tucková L, Sebo P, Michalak M, Whelan A, Sterzl I, Jelínková L, Havrdová E, Imramovská M, Benes Z. Occurrence of IgA and IgG autoantibodies to calreticulin in coeliac disease and various autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmun. 2000;15:441-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sánchez D, Tucková L, Mothes T, Kreisel W, Benes Z, Tlaskalová-Hogenová H. Epitopes of calreticulin recognised by IgA autoantibodies from patients with hepatic and coeliac disease. J Autoimmun. 2003;21:383-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hernandez L, Johnson TC, Naiyer AJ, Kryszak D, Ciaccio EJ, Min A, Bodenheimer HC, Brown RS, Fasano A, Green PH. Chronic hepatitis C virus and celiac disease, is there an association? Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:256-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Leonardi S, La Rosa M. Are hepatitis B virus and celiac disease linked? Hepat Mon. 2010;10:173-175. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Kaukinen K, Halme L, Collin P, Färkkilä M, Mäki M, Vehmanen P, Partanen J, Höckerstedt K. Celiac disease in patients with severe liver disease: gluten-free diet may reverse hepatic failure. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:881-888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mirzaagha F, Azali SH, Islami F, Zamani F, Khalilipour E, Khatibian M, Malekzadeh R. Coeliac disease in autoimmune liver disease: a cross-sectional study and a systematic review. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:620-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Volta U. Liver dysfunction in celiac disease. Minerva Med. 2008;99:619-629. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Mounajjed T, Oxentenko A, Shmidt E, Smyrk T. The liver in celiac disease: clinical manifestations, histologic features, and response to gluten-free diet in 30 patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:128-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Vanciková Z, Chlumecký V, Sokol D, Horáková D, Hamsíková E, Fucíková T, Janatková I, Ulcová-Gallová Z, Stĕpán J, Límanová Z. The serologic screening for celiac disease in the general population (blood donors) and in some high-risk groups of adults (patients with autoimmune diseases, osteoporosis and infertility) in the Czech republic. Folia Microbiol (Praha). 2002;47:753-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Dahmani Z, Jemaa Y, Moussa A, Benhammouda I, Debbeche R, Najjar T. [Celiac disease associated to Wilson disease]. Tunis Med. 2008;86:940-941. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Ince AT, Kayadibi H, Soylu A, Ovunç O, Gültepe M, Toros AB, Yaşar B, Kendir T, Abut E. Serum copper, ceruloplasmin and 24-h urine copper evaluations in celiac patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:1564-1572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Goyens P, Brasseur D, Cadranel S. Copper deficiency in infants with active celiac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1985;4:677-680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Lurie Y, Landau DA, Pfeffer J, Oren R. Celiac disease diagnosed in the elderly. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:59-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Rubio-Tapia A, Abdulkarim AS, Wiesner RH, Moore SB, Krause PK, Murray JA. Celiac disease autoantibodies in severe autoimmune liver disease and the effect of liver transplantation. Liver Int. 2008;28:467-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Peer reviewers: Dr. Orhan Sezgin, Professor, Department of Gastroenterology, Mersin University School of Medicine, 33190 Mersin, Turkey; Salvatore Leonardi, Assistant Professor, Department of Pediatrics, University of Catania, Via S Sofia 78, 95100 Catania, Italy

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Xiong L