Published online Oct 28, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i40.5816

Revised: June 19, 2012

Accepted: August 14, 2012

Published online: October 28, 2012

Several case reports deal with the relationship between hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and pulmonary or hepatic sarcoidosis. Most publications describe interferon α-induced sarcoidosis. However, HCV infection per se is also suggested to cause sarcoidosis. The present case report describes a case of biopsy-verified lung and liver sarcoidosis and HCV infection, and the outcome of antiviral therapy. In March 2009, a 25-year-old man presented with moderately elevated liver enzymes without any clinical symptoms. The patient was positive for HCV antibodies and HCV RNA of genotype 1b. Four months later the patient became dyspnoic and pulmonary sarcoidosis was diagnosed by lung biopsy and radiography. A short course of corticosteroid treatment relieved symptoms. Three months later, liver biopsy showed noncaseating granulomas consisting of epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells with a small amount of peripheral lymphocyte infiltration, without any signs of fibrosis. Chronic HCV infection with coexistence of pulmonary and hepatic sarcoidosis was diagnosed. Antiviral therapy with peginterferon α and ribavirin at standard doses was started, which lasted 48 wk, and sustained viral response was achieved. A second liver biopsy showed disappearance of granulomas and chest radiography revealed normalization of mediastinal and perihilar glands. The hypothesis that HCV infection per se may have triggered systemic sarcoidosis was proposed. Successful treatment of HCV infection led to continuous remission of pulmonary and hepatic sarcoidosis. Further studies are required to understand the relationship between systemic sarcoidosis and HCV infection.

- Citation: Brjalin V, Salupere R, Tefanova V, Prikk K, Lapidus N, Jõeste E. Sarcoidosis and chronic hepatitis C: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(40): 5816-5820

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i40/5816.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i40.5816

The estimated global prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is around 3%, corresponding to 170 million infected people[1]. As estimated, up to 1% of 1.34 million of the Estonian population are infected with HCV and this virus was reported to be the main etiological agent for chronic hepatitis and liver cirrhosis in Estonian patients[2]. After acute infection, chronic hepatitis develops in up to 80% of cases and may lead to hepatic and extrahepatic complications. There have been reported more than 30 extrahepatic manifestations of chronic HCV infection[3]. The best documented manifestation is essential mixed cryoglobulinemia. Non-cryoglobulin diseases having a relationship with HCV include idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, lichen planus, Sjogren syndrome, autoimmune thyroiditis, porphyria cutanea tarda, chronic polyarthritis and some others[4].

Sarcoidosis is a systemic inflammatory disease of unknown etiology with the presence of noncaseating epithelioid cell granulomas in many organs. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is based on a compatible clinical and/or radiological picture, histological evidence of noncaseating granulomas and the exclusion of other diseases having a similar histological or clinical picture[5].

The prevalence of sarcoidosis in the general population varies throughout the world from less than one case to 40 cases per 100 000 people or 0.001%-0.04%[5,6]. The prevalence of sarcoidosis in HCV-infected patients is reported to be 0.1%-0.2%[7,8]. A relationship between systemic sarcoidosis and HCV infection may emerge due to antiviral therapy with interferon α and ribavirin (in 75% of cases), or owing to unknown factor(s)[9]. Coexistence of sarcoidosis and untreated HCV infection prompted some authors to suggest that HCV infection per se can induce sarcoidosis[10]. The decision to start antiviral therapy for HCV infection in patients with pre-existing sarcoidosis is a delicate challenge for the clinician, calling for close monitoring[9].

This case report describes the clinical and histological characteristics of systemic sarcoidosis and chronic HCV infection, and the successful outcome of antiviral therapy.

In March 2009, a 25-year-old male patient was referred to the gastroenterologist at the West-Tallinn Central Hospital with moderately elevated liver enzymes: alanine aminotransferase (ALAT) 111 U/L (reference range < 42 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase 44 U/L (reference range < 37 U/L); and with positive HCV antibodies. According to his case history, elevated liver enzymes were also observed during a routine visit to the family doctor in December 2008.

The patient denied intravenous drug abuse, any occupational exposures and blood transfusions in the past. The time and manner of acquisition of HCV infection remained uknown. The patient did not have any symptoms of liver disease. Human immunodeficiency virus, surface antigen of the hepatitis B virus and autoantibodies; i.e., antinuclear antibodies, anti-mitochondrial M2-antibodies, anti-liver-kidney microsome antibodies and anti-smooth muscle antibodies, were negative. The values of ferritin, thyroid-stimulating hormone and ceruloplasmin were within the reference ranges. The patient was infected with HCV genotype 1b determined by the hybridization technique (VERSANT HCV genotype assay); the viral load was 723 000 IU/mL as analysed by the polymerase chain reaction assay (COBAS® AmpliPrep/COBAS® TaqMan). Abdominal ultrasound revealed no changes in liver size and appearance, nor was there noted any pathology in the other internal organs.

The diagnosis was chronic hepatitis C of unknown origin. Antiviral treatment was offered, but the patient for some reason postponed treatment and decided to start it several months later.

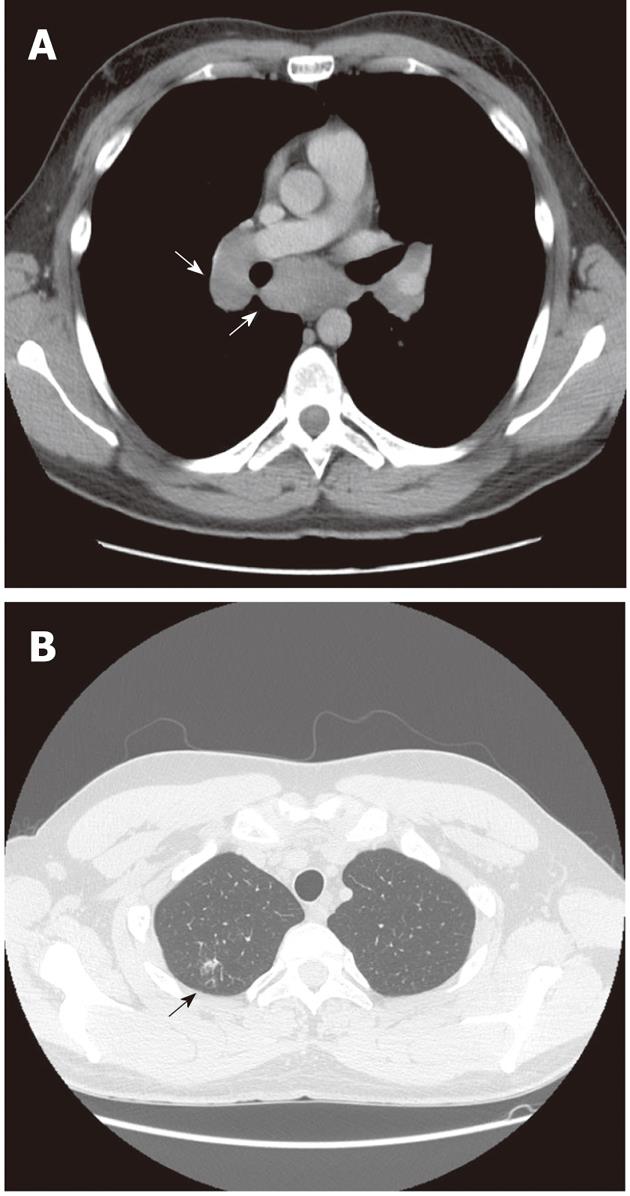

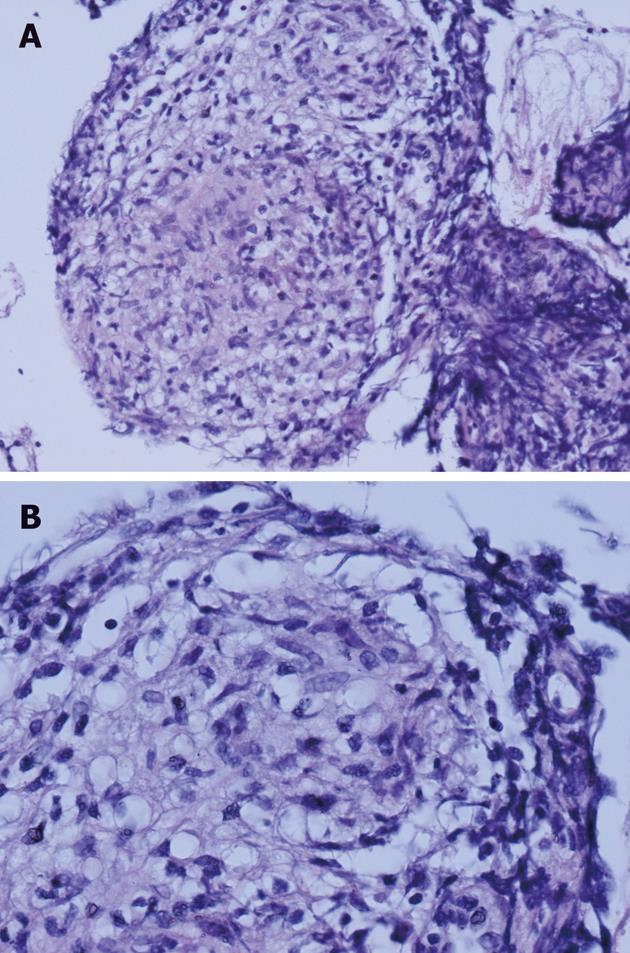

In July 2009, the patient was referred to the pulmonologist due to erythema nodosum on his legs, and dyspnea and cough. Computer tomography (CT) scans of the chest showed mediastinal and hilar adenopathy and focal lesions in the right upper lung lobe (Figure 1). Transbronchial biopsy of pulmonary lymph nodes was performed, which revealed epithelioid cell granulomas (Figure 2). Systemic sarcoidosis was diagnosed and corticosteroid treatment with prednisolone 20 mg orally was started. After one month of corticosteroid therapy the skin lesions disappeared. As the patient did not experience any symptoms, he discontinued prednisolone treatment.

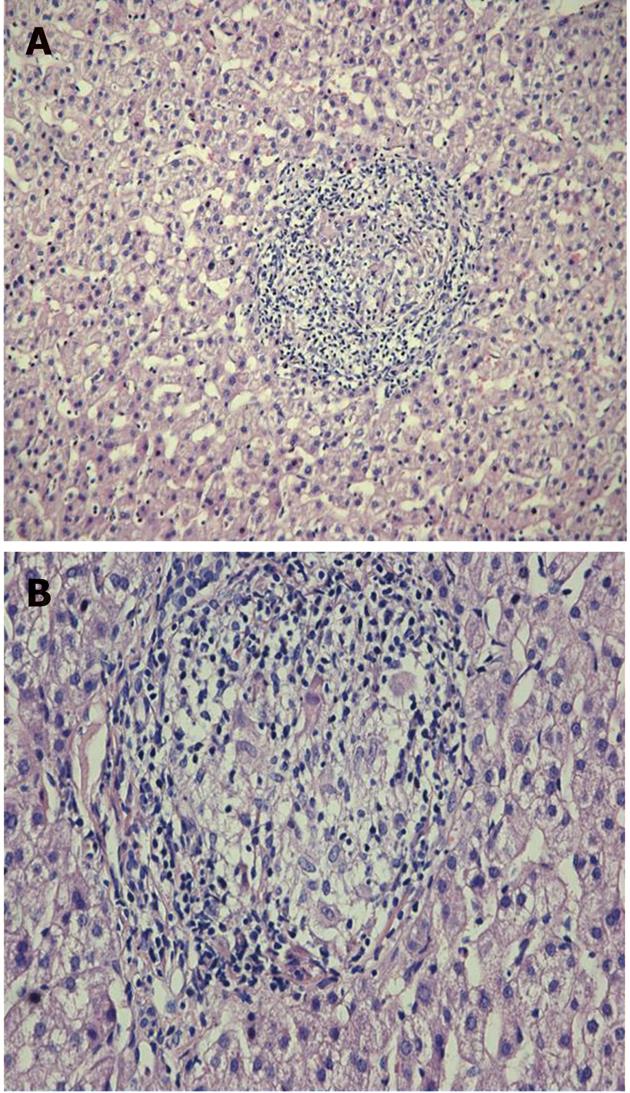

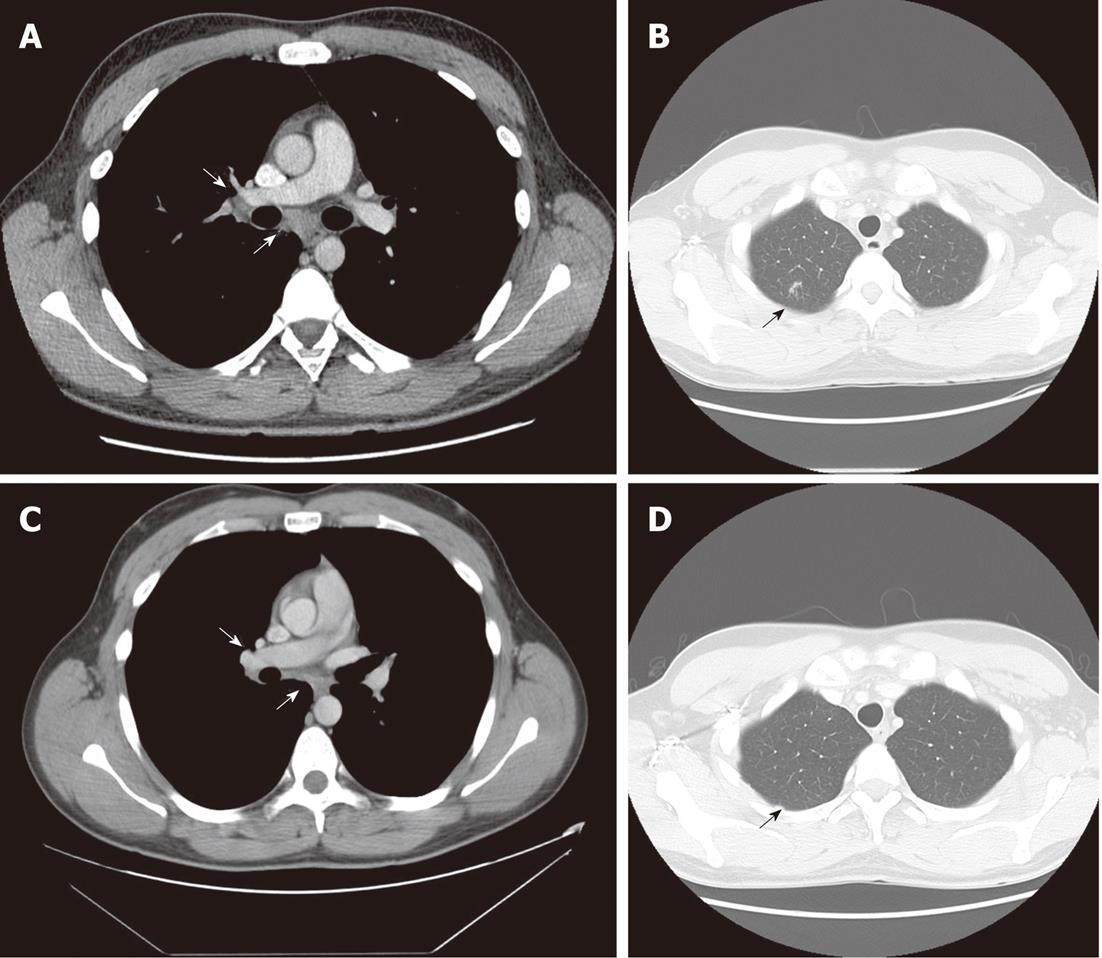

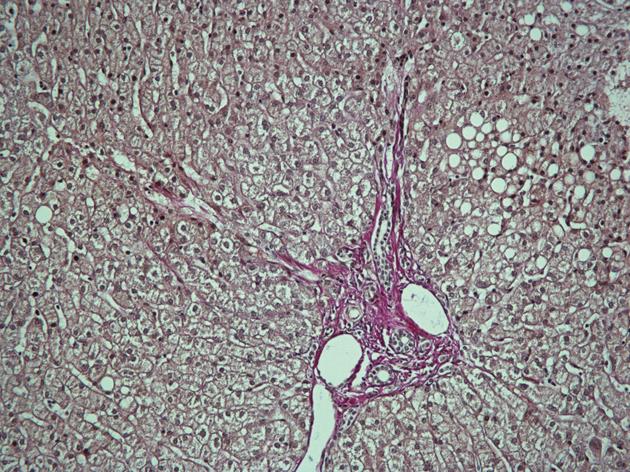

In October 2009, the patient still had elevated ALAT (60 U/L) and the viral load was 687 000 IU/mL. Ultrasound-guided liver biopsy was performed. It revealed 3 noncaseating granulomas consisting of epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells with weak peripheral lymphocyte infiltration, without any signs of fibrosis specific for chronic hepatitis C (Figure 3). His chest CT scans showed mild regression of lung sarcoidosis: mediastinal lymph nodes had became smaller while all other pathological findings remained the same (Figure 4A and B). The patient was diagnosed with chronic hepatitis C with coexisting pulmonary and hepatic sarcoidosis.

Taking into consideration that there was no exacerbation of pulmonary sarcoidosis and that the patient had chronic hepatitis C, antiviral therapy was opted for: peginterferon α-2a (Pegasys, F.Hoffmann La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland) at a dose of 180 μg once a week subcutaneously and 1200 mg of ribavirin (Copegus, F.Hoffmann La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland) daily orally was started. At week 4, the viral load decreased to 4755 IU/mL and no HCV RNA was found at weeks 12 and 24. The patient completed antiviral therapy at week 48 with normal liver enzymes and negative HCV RNA. At the end of treatment, chest CT scans showed a decrease in mediastinal and hilar adenopathy with disappearance of focal lesions in the upper lobe of the right lung (Figure 4C and D).

During treatment the patient experienced some side effects (fatigue, weight loss of 5 kg); he developed neutropenia and anemia but there was no need to change the doses of antiviral medications.

Six months after the end of treatment the patient had negative HCV RNA and his liver enzymes were normal. Sustained viral response (SVR) was documented. CT scans showed small mediastinal lymph nodes about 0.5 cm in diameter, and absence of hilar adenopathy and focal lesions in the upper lobe of the right lung.

Five months after SVR was confirmed, a new liver biopsy was performed which showed no remnant granulomas and mild steatosis in the liver tissue (Figure 5). No corticosteroid treatment was given after the first treatment course in July.

Sarcoidosis is a chronic multi-systemic granulomatous disease of unknown etiology related to exaggerated cellular immunological reactions[11]. The lungs, the liver, the lymph nodes, and the skin are commonly involved.

Here, we present a case of systemic sarcoidosis with the example of a treatment-naive patient with HCV 1b infection. The patient was first diagnosed as symptom-free with chronic HCV infection. Four months later, lung symptoms developed and the diagnosis was pulmonary sarcoidosis. The complaints - cough and dyspnea, as well as erythema nodosum - were relieved by the administration of oral corticosteroids. Three months later a liver biopsy revealed hepatic granulomas. Chronic HCV infection with coexistence of pulmonary and hepatic sarcoidosis was diagnosed. The patient started and completed a full 48-wk course of antiviral therapy without aggravating lung symptoms.

According to Ramos-Casals et al[9], sarcoidosis during antiviral therapy (in 75% of cases) has mainly a benign uncomplicated evolution, while more complicated cases are observed especially in HCV patients with preexisting sarcoidosis both with and without previous antiviral therapy.

In our studied HCV treatment-naive patient, systemic sarcoidosis was unrelated to antiviral therapy. In sarcoidosis observed in treatment-naive patients with HCV infection, skin involvement is less frequent than in sarcoidosis triggered by antiviral therapy. In the former case, systemic corticosteroids have to be used more often and the outcome appears less favorable[8]. In our patient, corticosteroid therapy for sarcoidosis was given for only a month when the patient discontinued therapy. Despite this, the outcome of therapy was favorable: the skin lesions disappeared, and progression of lung sarcoidosis or exacerbation of HCV infection was not noted.

In the case of pre-existing sarcoidosis the decision about starting antiviral therapy under close monitoring should be made very cautiously[8,9]. According to Charlier et al[12], reactivation of pre-existing sarcoidosis in HCV patients is rare and the manifestations of the disease are not very severe. Bearing these aspects in mind, antiviral therapy with peginterferon α and ribavirin for treatment of chronic HCV infection was opted for in the present case. The therapy was successful and the patient achieved SVR. No reactivation of systemic sarcoidosis with skin, lung or hepatic involvement was observed. The absence of hepatic granuloma on the second liver biopsy, performed five months after SVR, demonstrated a favorable treatment result possibly preventing hepatic granuloma in our patient, which develops into liver cirrhosis with life-threatening variceal bleeding in about 1% of these cases[13].

Our case report, as it considers hepatic involvement, is interesting in several aspects. Firstly, for sarcoidosis in the liver, the course of which is usually mild and transient, and clinically silent, granulomatous lesions are usually very small and asymptomatic[14,15]. In our patient the manifestations of liver disease were asymptomatic.

Corticosteroid treatment of hepatic sarcoidosis is used only for patients with severe liver lesions, such as chronic cholestatic disease, portal hypertension and cirrhosis[16].

Secondly, hepatic granulomas are not very rare in HCV disease. The prevalence of hepatic granulomas in liver biopsies of patients with chronic hepatitis C have been reported to be from 0.8% up to 9.5%[17-19] and only when other etiological factors of granuloma formation are excluded may it be considered as a part of the histologic spectrum of HCV[19]. In our treatment-naive HCV patient, noncaseating granuloma was found first in the lung lymph node and later liver biopsy also revealed granulomas, so coexistence of systemic sarcoidosis and chronic hepatitis C was diagnosed.

All these facts show that some similar specific immune pathogenic mechanisms may be involved in the course of systemic sarcoidosis and chronic HCV. It is possible that complex dysregulation of the cytokine/chemokine network in patients with HCV infection along with some other host factors might induce the release of certain mediators and activation of mononuclear phagocytes that finally cause a granulomatous reaction[20]. Although coexistence of both diseases in our case may be a coincidence, we, like Bonnet et al[10], suggest that HCV per se could be an antigenic trigger for development of sarcoidosis.

As systemic sarcoidosis may be reactivated after antiviral treatment, further close follow-up of our patient is needed.

In conclusion, physicians should be aware that HCV-infected patients may have systemic sarcoidosis unrelated to antiviral treatment. Also, it is obvious that further case-control studies focusing on sarcoidosis in patients with HCV infection and the relationship between sarcoidosis and antiviral therapy are needed.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

The authors would like to thank Anders Widell, Associate Professor, from the University of Lund, Malmö, Sweden for critical revision of our manuscript and Margarita Malish, nurse, from West-Tallinn Central Hospital for assistance in management of the HCV patient.

| 1. | Baldo V, Baldovin T, Trivello R, Floreani A. Epidemiology of HCV infection. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:1646-1654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tefanova V, Tallo T, Kutsar K, Priimgi L. Urgent action needed to stop spread of hepatitis B and C in Estonian drug users. Euro Surveill. 2006;11:E060126.3. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Agnello V, De Rosa FG. Extrahepatic disease manifestations of HCV infection: some current issues. J Hepatol. 2004;40:341-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zignego AL, Ferri C, Pileri SA, Caini P, Bianchi FB. Extrahepatic manifestations of Hepatitis C Virus infection: a general overview and guidelines for a clinical approach. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:2-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Costabel U, Hunninghake GW. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Statement Committee. American Thoracic Society. European Respiratory Society. World Association for Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:735-737. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Lazarus A. Sarcoidosis: epidemiology, etiology, pathogenesis, and genetics. Dis Mon. 2009;55:649-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Goldberg HJ, Fiedler D, Webb A, Jagirdar J, Hoyumpa AM, Peters J. Sarcoidosis after treatment with interferon-alpha: a case series and review of the literature. Respir Med. 2006;100:2063-2068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Faurie P, Broussolle C, Zoulim F, Trepo C, Sève P. Sarcoidosis and hepatitis C: clinical description of 11 cases. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:967-972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ramos-Casals M, Mañá J, Nardi N, Brito-Zerón P, Xaubet A, Sánchez-Tapias JM, Cervera R, Font J. Sarcoidosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: analysis of 68 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2005;84:69-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bonnet F, Morlat P, Dubuc J, De Witte S, Bonarek M, Bernard N, Lacoste D, Beylot J. Sarcoidosis-associated hepatitis C virus infection. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:794-796. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2153-2165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1469] [Cited by in RCA: 1472] [Article Influence: 77.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Charlier C, Nunes H, Trinchet JC, Roullet E, Mouthon L, Beaugrand M, Valeyre D. Evolution of previous sarcoidosis under type 1 interferons given for severe associated disease. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:570-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yoshiji H, Kitagawa K, Noguchi R, Uemura M, Ikenaka Y, Aihara Y, Nakanishi K, Shirai Y, Morioka C, Fukui H. A histologically proven case of progressive liver sarcoidosis with variceal rupture. World J Hepatol. 2011;3:271-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Valla DC, Benhamou JP. Hepatic granulomas and hepatic sarcoidosis. Clin Liver Dis. 2000;4:269-285, ix-x. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rose AS, Tielker MA, Knox KS. Hepatic, ocular, and cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2008;29:509-524, ix. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ayyala US, Padilla ML. Diagnosis and treatment of hepatic sarcoidosis. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2006;9:475-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ozaras R, Tahan V, Mert A, Uraz S, Kanat M, Tabak F, Avsar E, Ozbay G, Celikel CA, Tozun N. The prevalence of hepatic granulomas in chronic hepatitis C. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:449-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gaya DR, Thorburn D, Oien KA, Morris AJ, Stanley AJ. Hepatic granulomas: a 10 year single centre experience. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:850-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Snyder N, Martinez JG, Xiao SY. Chronic hepatitis C is a common associated with hepatic granulomas. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6366-6369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fallahi P, Ferri C, Ferrari SM, Corrado A, Sansonno D, Antonelli A. Cytokines and HCV-related disorders. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:468107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Peer reviewers: Dr. Mihaela Petrova, MD, PhD, Clinic of Gastroenterology, Medical Institute, Ministry of Interior, 1606 Sofia, Bulgaria; Dr. Justin MM Cates, MD, PhD, Department of Pathology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Medical Center North, C-3322, 1161 21st Avenue South, Nashville, TN 37232, United States

S- Editor Shi ZF L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Xiong L