CASE REPORT

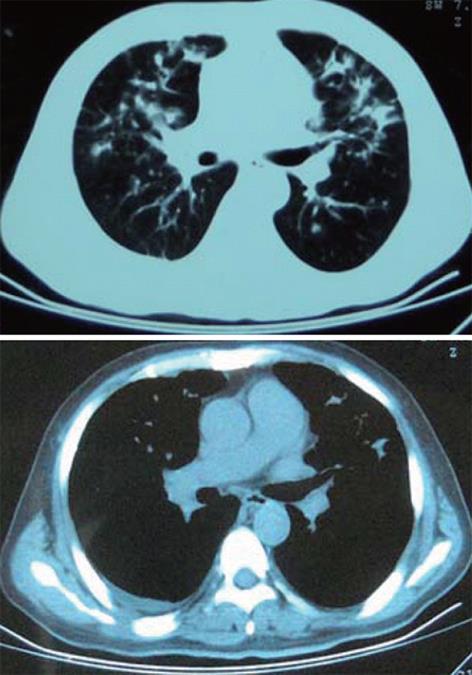

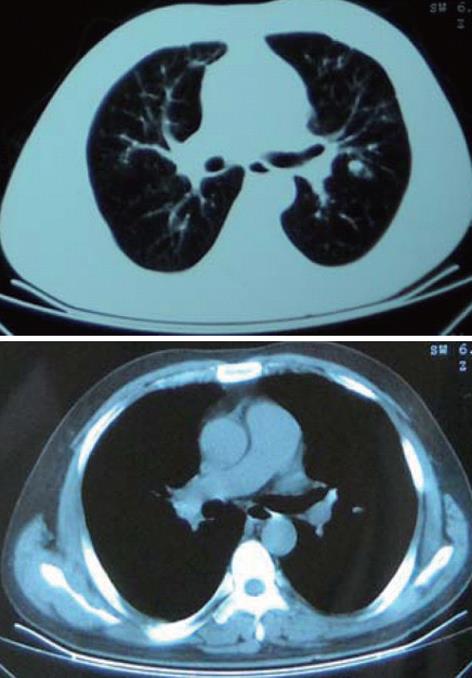

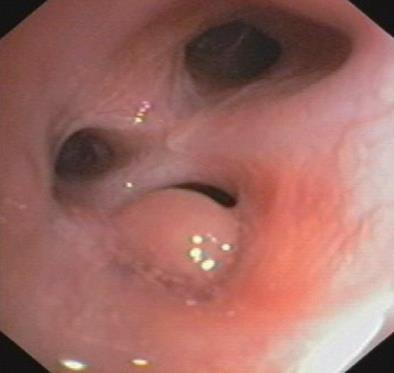

A 42-year-old man was admitted to our department because of a slow onset of cough and pyrexia in January 19, 2009. Forty days prior to this presentation, severe abdominal pain and diarrhea led to his referral to abdominal computed tomography (CT) that revealed free gas under the diaphragm. The patient underwent celiotomy. During operation, multiple broken colon was identified and pancolectomy was performed. The pathology of resected specimen revealed Crohn’s disease of colon. His symptoms were resolved after the operation. On admission, he was expectorating about 20 mL of grossly frothy sputum per day and he had a pyrexia of 37.7 °C. Laboratory data on admission were: white cell counts 8.5 × 109/L, 63% segmented neutrophils, a moderate increase of erythrocyte sedimentation rate (30 mm in the first hour). A CT scan of the chest revealed bilateral lung patchy shadows (Figure 1). Initial treatment consisted of intravenous azithromycin (0.5 g, once a day) with aztreonam (2.0 g, twice a day) for 2 wk. A search for bacterial (including mycobacteria) and fungal in the repeated sputum proved negative. The purified protein derivative skin test and cytoplasmic-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (c-ANCA) were also negative. Intravenous cefoperazone/sulbactam (3.0 g, twice a day) was substituted for 2 wk, but there was no improvement in pyrexia or cough, and his chest CT revealed no dissipation. On day 36 after admission, the patient underwent fibreoptic bronchoscopy (FOB) which showed nodes in the trachea and the right upper lobe opening (Figure 2). Transbronchial lung biopsy was performed in tracheobronchial nodules and left lingular lobe. Histopathology of tracheobronchial nodules and bronchial mucosa biopsy specimen both showed granulomatous inflammation with proliferation of capillaries and inflammatory cells (Figure 3). Fibercoloscope was performed in the following day, which showed cobblestones in the residual sigmoid colon. On day 55, antibiotic treatment was discontinued and the patient was started on prednisone 50 mg daily and salicylazosulfapyridine (SASP) (1.0 g, four times a day) for a presumptive diagnosis of Crohn’s disease related tracheobronchial nodules and tracheobronchitis associated with pulmonary infiltrates. Within 48 h, the patient’s temperature turned normal. There was improvement in cough and the volume of sputum being expectorated a week later. A follow-up CT 3 wk later showed disappearance of the bilateral patchy shadows (Figure 4). He underwent repeated FOB in the following day which showed that nodes in the trachea disappeared and the ones in the right upper lobe opening diminished obviously (Figure 5).

Figure 1 Computed tomography scan of the thorax (January 19, 2009), showing multiple patchy shadows in both lung fields with a little right pleural effusion.

Figure 2 Fibreoptic bronchoscopy (March 9, 2009), showing nodes in the right upper lobe opening.

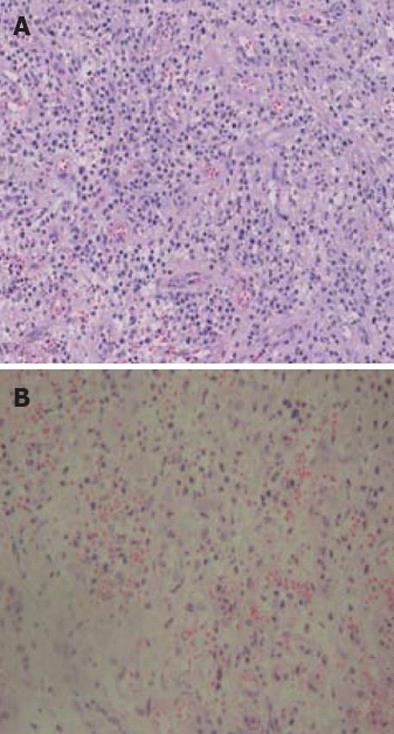

Figure 3 Transfiberoptic bronchoscopy mucosal biopsy, showing polypoid hyperplasia of granulation tissue and hyperplasia of capillary with inflammatory cells (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×200).

A: Tracheobronchial nodules; B: Left lingular lobe.

Figure 4 Computed tomography scan of the thorax (April 5, 2009), showing multiple patchy shadows in both lung fields almost disappeared.

Figure 5 Fibreoptic bronchoscopy (April 6, 2009), showing nodes in the right upper lobe opening diminished obviously.

DISCUSSION

Crohn’s disease is a granulomatous inflammation of unknown etiology that mainly affects the small bowel, although extracolonic manifestations are common. Extraintestinal manifestations occur in at least 25% of Crohn’s disease patients, most commonly in the skin and genitourinary system[6]. It has been rarely reported in the lung. The overall prevalence of concomitant bronchopulmonary manifestations is as low as 0.4%[7]. Several forms of involvement of the lung parenchyma are recognized[8-11]. Diffuse, nongranulomatous interstitial inflammatory lymphoid infiltration has also been described in Crohn’s disease[12].

The clinical features of extraintestinal involvement in our patient seem to be interesting for several reasons. Both tracheal-bronchus and lung parenchyma are involved. Transfiberoptic bronchoscopy biopsy of the tracheobronchial nodules and bronchial mucosa in the left lingular lobe revealed a benign, nongranulomatous inflammation with proliferation of capillaries and inflammatory cells. Although tracheobronchial involvement in Crohn’s disease has been described in literature, the extent of involvement seen in the current patient with nodules in trachea and right upper lobe bronchus, seems quite unusual. There are few previous reports of tracheobronchial nodules. Crohn’s disease can involve the lung parenchyma, the tracheobronchial tree, and the pleura[13]. The patient underwent colectomy prior to admission. The pulmonary manifestations of Crohn’s disease in some patients may only become clinically remarkable after surgery[14]. Colectomy may aggravate respiratory symptoms[15]. However, the pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease-related airway disease remains unknown. It may involve an inflammatory component because a large proportion of these patients are responsive to steroid therapy. The lung and the gastrointestinal tract have a similar embryological origin (a potential source of common antigenicity), and some authors considered a breakdown in the intestinal barrier and entry of dietary antigens as the cause of extracolonic involvement in Crohn’s disease[16]. One proposed mechanism is that many of the extraintestinal manifestations of Crohn’s disease, including lung disease, are secondary to circulating inflammatory mediators released by the inflamed bowel mucosa[17]. These inflammatory mediators may survive in the pulmonary system for a long time, causing smoldering injuries. This explains the development of pulmonary disease after colectomy in some of the patients with Crohn’s disease.

Clinically, when assessing the relationship between respiratory disease and Crohn’s disease, one should always keep in mind that the two conditions may have occurred together simply by chance, and therefore other differential diagnoses should be made, such as sarcoidosis, a systemic vasculitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis or Churg-Strauss disease), or a prior pulmonary process. In the current patient, the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease was initially clearly established on histological grounds of the resected bowel specimen. Although sarcoidosis and Crohn’s disease may coexist in the same patient[18], the absence of typical sarcoid granulomata in tracheobronchial biopsies, and the lack of evidence for extrapulmonary sarcoid involvement led the authors to rule out sarcoidosis. In view of the absence of histological findings suggestive of Wegener’s granulomatosis, the lack of c-ANCA and no extrapulmonary involvement, the diagnosis of Wegener’s granulomatosis was unlikely. Post-obstructive pneumonia results from airway obstruction, commonly due to lung cancer. A mismatch in scope of bilateral and diffuse lung infiltrates with tracheobronchial nodules excluded a diagnosis of post-obstructive pneumonia.

The initial lesion of tracheobronchial Crohn’s disease seems to be mucosal inflammation, with symptoms of cough and pyrexia[19]. Mucosal inflammation may be accompanied by bronchial suppuration. Biopsy shows either severe nonspecific chronic inflammation or non-caseating tuberculoid granulomas. These appearances have been associated with those in the bowel, and it is possible that the gut and the lung are both affected because they share common antigens. The lung and gastrointestinal tract contain submucosal lymphoid tissues and play crucial roles in host mucosal defense. The similarity in the mucosal immune system causes the same pathogenetic changes. The clinical courses between upper airway and gastrointestinal tract disease are not entirely parallel[20]. It was thought that the tracheobronchial nodules and pulmonary infiltrates were both caused by Crohn’s disease, because the pathological finding resembled that of the colon. In addition, they almost vanished as good response to steroids while multiple antibiotic regimens failed to produce clinical improvement.

Drug-induced disease must be kept in mind in patients taking sulfasalazine, mesalamine, methotrexate, and anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Sulfasalazine and 5-aminosalicylic acid derivatives have been reported to cause interstitial pneumonitis, eosinophilic pneumonia, or bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia in rare cases[21,22]. Other commonly used medications in inflammatory bowel disease patients include 6-mercaptopurine, azathioprine, and methotrexate. These drugs may also cause pneumonia via opportunistic infections, or acute pneumonitis or pulmonary fibrosis[23]. Lung abnormalities observed in our patient were unrelated to pharmacological treatment.

Patients with pulmonary involvement of Crohn’s disease can be cured with glucocorticoid and SASP, for they are strikingly steroid-responsive frequently. Pulmonary manifestations almost vanished after receiving oral prednisone and SASP in the present case. In all patients with airway disease, marked and long-lasting responses were seen following systemic or inhaled administration of steroids. These findings were not commonly observed for patients with chronic bronchitis without Crohn’s disease. Intravenous steroids were required in the initial management of life-threatening complications such as asphyxiating subglottic stenosis or extensive interstitial lung disease. Bronchial lavages with methylprednisolone were effective in some patients with severe airway inflammation. Bronchoscopic dilatation or stent placement should be considered in cases of tracheal stenosis due to Crohn’s disease refractory to steroid treatment[24]. Other interventional pulmonology techniques, such as bronchoscopic resection or ablation, could not be generally indicated for treatment modalities potentially contraindicated because of the risk of stenosis or fistula.

In summary, this case illustrates a rare form of tracheal and bronchopulmonary involvement in Crohn’s disease with nodes and multiple patchy shadows in both lung fields. As is the case with other forms of pulmonary involvement in Crohn’s disease, this manifestation responded well to steroids. It is believed that early investigation and vigorous treatment of bronchopulmonary involvement of Crohn’s disease is essential.