Published online Oct 21, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i39.5649

Revised: June 1, 2012

Accepted: June 15, 2012

Published online: October 21, 2012

Here, we present the case of a 53-year-old man with a hepatothorax due to a right diaphragmatic rupture related to duodenal ulcer perforation. On admission, the patient complained of severe acute abdominal pain, with physical examination findings suspicious for a perforated peptic ulcer. Of note, the patient had no history of other medical conditions or recent trauma, and the initial chest radiography and laboratory findings were not specific. A subsequent abdominal computed tomography revealed intrathoracic displacement of the liver, gallbladder, transverse colon and omentum through a right diaphragmatic defect. The patient then underwent an explorative laparotomy that confirmed duodenal ulcer perforation. A primary repair of the duodenal perforation was performed, and the diaphragmatic defect was repaired using a polytetrafluoroethylene patch after the organs were reduced and the cavity irrigated. This particular case proves interesting as right-sided spontaneous diaphragmatic ruptures are very rare and difficult to diagnose. Additionally, the best treatment for such large diaphragmatic defects is still controversial, especially in cases of intrathoracic or intra-abdominal contamination.

- Citation: Baek SJ, Kim J, Lee SH. Hepatothorax due to a right diaphragmatic rupture related to duodenal ulcer perforation. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(39): 5649-5652

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i39/5649.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i39.5649

Non-traumatic, spontaneous diaphragmatic ruptures are extremely rare, accounting for approximately 1% of all diaphragmatic ruptures. Here, we present the case of an acute right diaphragmatic rupture related to duodenal ulcer perforation which resulted in displacement of the liver, gallbladder, transverse colon and omentum into the intrathoracic cavity.

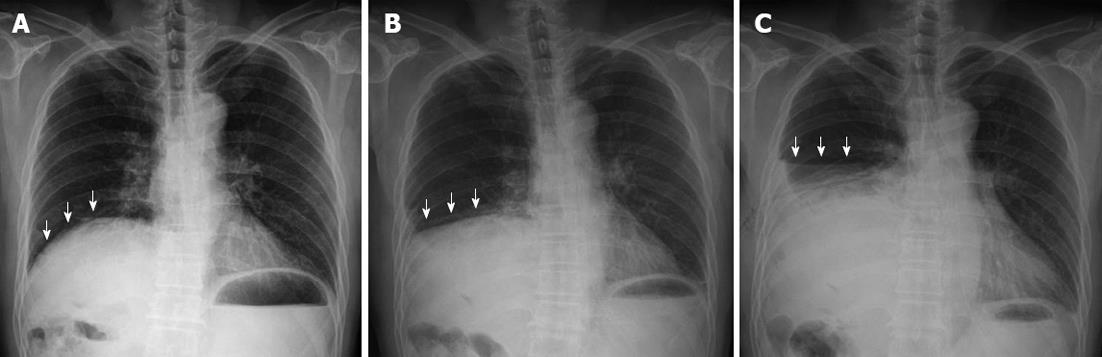

A 53-year-old male patient presented to the emergency room complaining of acute abdominal pain, which reportedly started 30 min previously. Of note, he denied any relevant past medical history, any recent trauma, and any medication use. At the time of admission, the patient continued to complain of severe epigastric pain, and a physical exam revealed a rigid abdomen, with both tenderness and rebound tenderness observed throughout the abdomen. His vital signs were relatively stable, with a blood pressure of 120/80 mmHg, a heart rate of 95 beats per minute, oxygen saturation of 98%, and a body temperature of 37 °C. The initial chest radiograph revealed a slight elevation of the right diaphragmatic border, though at the time this was not deemed to be significant (Figure 1A). Further laboratory findings showed no other abnormalities, such as anemia or leukocytosis (Figure 1).

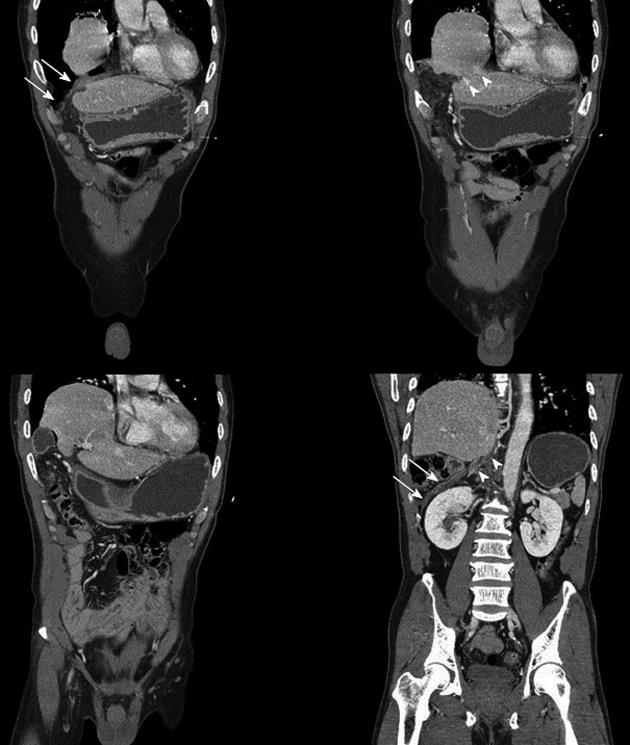

Due to the generalized peritonitis on the physical exam, a perforated peptic ulcer was suspected, and thus an abdominal computed tomography (CT) was performed. Unexpectedly, no free air or fluid collections were observed in the abdominal cavity. Instead, the CT showed significant displacement of the right lobe of the liver, the bowel and the omentum into the right hemithorax, with the reformatted coronal images providing better views of the right diaphragmatic border and showing a loss of a part of the diaphragm (Figure 2). Notably, pneumothorax and hydrothorax were also observed, and an injury to the lung parenchyma could not be ruled out.

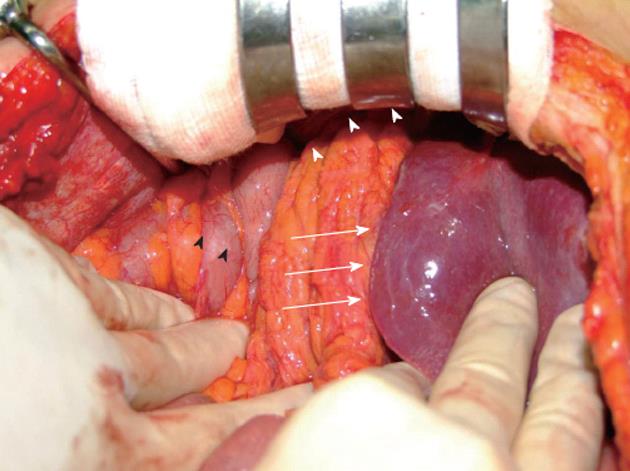

Initially, a tube thoracostomy was performed, with significant care taken to avoid any injury to the liver and/or bowel. As foul-smelling fluid and bowel contents were noted in the drainage from the chest tube, bowel perforation was also suspected along with diaphragmatic rupture. Accordingly, an exploratory upper midline laparotomy was performed 4 h after admission. At first no evidence of bowel perforation - such as fluid collection or fecal material - was observed in the abdomen. Instead, only the left lobe of the liver was found to have protruded into the right upper abdomen, with the right lobe rotated and herniated into the right hemithorax through the right diaphragmatic defect, along with the gallbladder, transverse colon, and omentum (Figure 3). Exploration of the entire abdomen revealed the site of perforation (approximately 0.5 cm in size) at the first portion of the duodenum immediately distal to the pylorus. Before reducing the herniated organs, a primary repair of the duodenal perforation was performed.

The medial portion of the right side of the diaphragm was nearly lost, with only the lateral portion remaining. As this lateral segment blocked reduction, the herniated organs were returned to their respective appropriate locations after the lateral diaphragm was incised, leaving a 12 cm × 10 cm defect. Because of the large size of this defect, primary repair was not possible. Accordingly, another chest tube was inserted just above the diaphragm after the thoracic cavity was thoroughly irrigated. Repair of the diaphragmatic rupture was then performed using a polytetrafluoroethylene patch (GoreTex; W.L. Gore, Flagstaff, AZ, United States) with 1-0 prolene sutures. No other evidence of perforation was noted in the herniated bowel. The abdominal cavity was then irrigated, and an omental patch was applied to the site of the duodenal perforation repair. After surgery, the patient was immediately sent to the intensive care unit for mechanical ventilation, whereby the thoracostomy tubes and abdominal drains were removed in sequence. A post-operative chest radiograph revealed that the right diaphragmatic border had returned to a normal position (Figure 4). After marked improvement in duodenal edema, the patient was discharged on post-operative day 20 with no further complications. Although the patient took oral antibiotics for only one week after discharge, no postoperative complications, including infections, occurred during the following year.

Diaphragmatic rupture is a rare complication of abdominal or thoracic trauma, reported in 1%-7% of major blunt trauma patients and 10%-15% of penetrating trauma patients[1,2]. However, approximately 1% of all diaphragmatic ruptures occur spontaneously, often resulting from a sudden increase in abdominal pressure secondary to heavy physical effort, sudden twisting movements, childbirth, and/or severe coughing[3-5]. Other cases have been reported to be caused by static sport activities (e.g., Pilates) or associated with endometriosis[6]. As the patient described here had no recent history of trauma, the exact reason for his diaphragmatic rupture remains unclear. However, given the clinical context, we conjecture that leaked digestive juice may have corroded the diaphragm, as occurs in cases of empyema. Another possibility is that portions of the diaphragm, such as the septum, may have been weakened or altered by previously unrecognized trauma. If this occurred, the pain resulting from the subsequent duodenal ulcer perforation and the associated abdominal muscle tension may have increased the intra-abdominal pressure, thus prompting the weakened diaphragm to rupture. We cannot determine the exact order of these incidents with any certainty. However, for whatever reason, the perforation of the duodenal ulcer seems to have acted as the precipitating event for the diaphragmatic rupture. Roughly 90% of diaphragmatic ruptures occur on the left side[1,2]. Right-sided diaphragmatic ruptures are comparatively rare and difficult to diagnose, as chest radiography often does not reveal any specific signs other than elevation of the right diaphragmatic border. Accordingly, delayed diagnosis is common in right-sided ruptures, often resulting in severe complications, such as strangulation ileus and intrathoracic herniation of the hollow organs (stomach, colon, and small bowel)[2,3].

The initial diagnostic tool is conventional chest radiography, though this modality has limited sensitivity and specificity (17%-40%). Currently, CT is most helpful for emergency diagnosis, as the coronal and sagittal reformatted images offer superior diagnostic value for right diaphragmatic rupture, with a specificity of nearly 100% and a sensitivity of 50%[7,8].

Cases of right diaphragmatic rupture with hepatothorax may result in severe atelectasis of the right lung or tension mediastinum, thereby severely impeding respiration and circulation. As such, if concern exists for right diaphragmatic rupture, an abdominal CT should be performed quickly, and surgical repair via a trans-thoracic or trans-abdominal approach should be considered immediately following radiographic confirmation. Because the size of the defect is often too large for a primary repair to be performed, prosthetic mesh may prove necessary[9,10]. Mesh infection was a significant concern in the case described here, given the intra-abdominal and intra-thoracic contamination from the bowel perforation. Fortunately, such complications did not occur and were likely prevented by the extensive irrigation and intensive antibiotic therapy.

| 1. | Wirbel RJ, Mutschler WE. Right-sided diaphragmatic rupture with intrathoracic displacement of the entire right lobe of the liver. Unfallchirurg. 1997;100:249-252. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Igai H, Yokomise H, Kumagai K, Yamashita S, Kawakita K, Kuroda Y. Delayed hepatothorax due to right-sided traumatic diaphragmatic rupture. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;55:434-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kara E, Kaya Y, Zeybek R, Coskun T, Yavuz C. A case of a diaphragmatic rupture complicated with lacerations of stomach and spleen caused by a violent cough presenting with mediastinal shift. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2004;33:649-650. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Gupta V, Singhal R, Ansari MZ. Spontaneous rupture of the diaphragm. Eur J Emerg Med. 2005;12:43-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ozgüç H, Garip G, Kirdak T. A case of diaphragmatic rupture after strenuous exercise (swimming) and jump into the sea. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2009;15:188-190. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Yang YM, Yang HB, Park JS, Kim H, Lee SW, Kim JH. Spontaneous diaphragmatic rupture complicated with perforation of the stomach during Pilates. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:259.e1-259.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shanmuganathan K, Mirvis SE. Imaging diagnosis of nonaortic thoracic injury. Radiol Clin North Am. 1999;37:533-551, vi. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Killeen KL, Shanmuganathan K, Mirvis SE. Imaging of traumatic diaphragmatic injuries. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2002;23:184-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Draaisma WA, Simmermacher RK, Broeders IA. Recurrent paraesophageal hernia due to diaphragm rupture: a case report. Hernia. 2006;10:282-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Seket B, Henry L, Adham M, Partensky C. Right-sided posttraumatic diaphragmatic rupture and delayed hepatic hernia. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:504-507. [PubMed] |

Peer reviewers: Dr. Michael Keese, Klinik für Gefässchirurgie, Universität Frankfurtm, Theodor-Stern-Kai 7, 60590 Frankfurt am Main, Germany; Dr. Michael Leitman, Department of Surgery, Beth Israel Medical Center, 10 Union Square East, Suite 2M, New York, NY 10003, United States; Dr. Frank Ivor Tovey, Department of Surgery, University College London, 5 Cossborough Hill, RG214AG Basingstoke, United Kingdom

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Rutherford A E- Editor Li JY