INTRODUCTION

Ischemic colitis (IC) was first described by Boley et al[1]. The condition is a common form of ischemic injury to the gastrointestinal tract and represents approximately one half of all cases involving gastrointestinal ischemia[2]. On average, this disease is found in association with approximately 1-3/1000 acute hospital admissions, but occasionally a mild and transient clinical course may lead to misdiagnoses. Elderly patients are typically affected, and the most common admission signs are hematochezia, abdominal pain and diarrhea[3]. The rapid onset of abdominal pain, tenderness over the affected bowel area (typically the left side of the colon) and mild to moderate hematochezia are the classic signs, although confusion can appear in cases that are considered to be inflammatory bowel disease or various forms of common bacterial colitis[4]. There is a lack of data regarding the natural history and outcomes of IC. A recent study[5] found that IC is clinically presumed in only 24.2% of cases, and unfavorable outcomes (as defined by mortality and/or the need for surgery) occur at a rate of 12.9%, including an overall mortality rate of 7.7%.

The taxonomy of the disease is somewhat unclear, especially when “puzzling” terms, such as ischemic colitis and colonic ischemia, are employed. According to the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) technical review on intestinal ischemia[6], ischemic bowel disease can be either acute or chronic. Whereas the acute condition includes various forms of acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI) up to intestinal infarction, the milder chronic variant includes chronic mesenteric ischemia (CMI) (also known as “intestinal angina”) and colonic ischemia (CI). CI can appear under various clinical-endoscopic aspects, including (1) reversible colopathy (submucosal or intramural hemorrhage); (2) transient colitis; (3) chronic colitis; (4) stricture; (5) gangrene; and (6) fulminant universal colitis. Most of these aspects have a mixed, ischemic-inflammatory pattern in which ischemic colitis results from an inadequate perfusion that leads to potentially life-threatening colonic inflammation[7]. In its chronic forms, healing is associated with a degree of fibrosis that determines colonic stenosis.

Beyond this almost scholastic classification, it is important to bear in mind that in current practice, these three major categories (AMI, CMI and CI) may be quite intricate. Moving from one to another occurs in a mix of clinical presentations that can appear in the same patient at various moments, depending on factors such as localization, extent of vascular disease, severity of ischemia, or bowel distension, among others. Our case reflects such a patient, in whom the clinical pattern changed several times in a couple of years. The case began as chronic “intestinal angina” and finished with signs of acute mesenteric ischemia after an episode of ischemic colitis.

CASE REPORT

We present the case of a male Caucasian patient who was monitored in our unit between 2006 and 2012. The hallmark of his long medical background was a severe vascular pathology that was facilitated by the combination of several risk factors: heavy smoking since the age of 18 (more than 20 cigarettes/d), type 2 diabetes that was poorly controlled by diet and medication for more than 15 years, obesity, dyslipidemia and moderate to severe hypertension since 1993. An episode of acute thrombosis of the left femoral artery occurred in 1999, which resulted in the amputation of his left thigh. The patient continued to smoke and neglect the recommended therapy, and four years later, he suffered another acute thrombotic episode, this time of the right lower limb with the occlusion of the popliteal artery. His right foot was amputated just below the knee. A complete hemostasis investigation was performed at that time, and there was no sign of coagulation abnormality (including less common genetic defects, such as deficiencies of protein C/S, antithrombin III, or factor V Leiden mutation). Aspirin and oral anticoagulation by coumadin were strongly recommended, but the patient appeared to disregard the advice by taking his treatment erratically. Finally, in 2005, a coronarography was performed to investigate an episode of unstable angina. The procedure showed a narrow stenosis (75%) of the circumflex artery; a stent (3.5 × 30 mm) was placed after the dilatation with a balloon catheter.

The patient was first hospitalized in the gastroenterology unit in September 2006, when he was 61 years old. The patient complained of postprandial pain that occurred especially after taking his medication, which consisted of beta blockers, thiazides, angiotensin enzyme inhibitors, aspirin, statins and coumadin. Gastroduodenal, biliary, pancreatic and colonic pathologies were eliminated by upper and lower digestive endoscopy, echography and computed tomography (CT) scans. The initial diagnosis was irritable bowel disease, but a lack of response to specific medication, the suggestive medical history and an improvement in the abdominal pain with sublingual nitroglycerin led to the suspicion of intestinal angina. A mesenteric arteriography was performed in January 2007, which showed a severe (> 75%) incomplete thrombotic occlusion of the upper mesenteric artery and a weak perfusion of the affected bowel loop (Figure 1). The case was concluded to be chronic mesenteric ischemia, but endovascular mesenteric revascularization or surgical bypass were not performed because of the patient’s lack of compliance. The patient was discharged with a prescription of long-acting nitrates, and pentoxyfillin was added to his antihypertensive, antiagregant and coumadin treatments.

Figure 1 Selective upper mesenteric artery angiogram showing severe incomplete thrombosis with more than a 75% reduction of the arterial lumen and poor perfusion of the bowel loop.

The evolution was more or less stable until March 2011, when the patient was re-admitted to the unit with episodes of persistent diarrhea and hematochezia, which were spaced by sub-occlusive events of colicky left-lower-quadrant abdominal pain and distension, vomiting and vasovagal symptoms. The examination showed mild pyrexia, tachycardia and a distended abdomen, and there was pain and tenderness in the left lower quadrant upon palpation. A digital rectal examination confirmed hematochezia but did not detect any other lesions. Laboratory investigations showed mild anemia (hemoglobin = 11.1 g/dL), neutrophil leukocytosis (14.800 leukocytes/mm3 with 78% neutrophils), increased values of ESR (130 mm/h), hyperfibrinogenemia (780 mg/dL) and elevated C-reactive protein titers (27 mg/L). Other biochemical tests were within normal ranges. A plain abdominal radiography did not detect pneumoperitoneum or air-fluid levels. The recent use of antibiotics was denied by the patient, and stool cultures for aerobic/anaerobic pathogens (Clostridium difficile included) were negative. Amoebiasis serology, a parasitological investigation and tuberculin intradermoreaction were also negative.

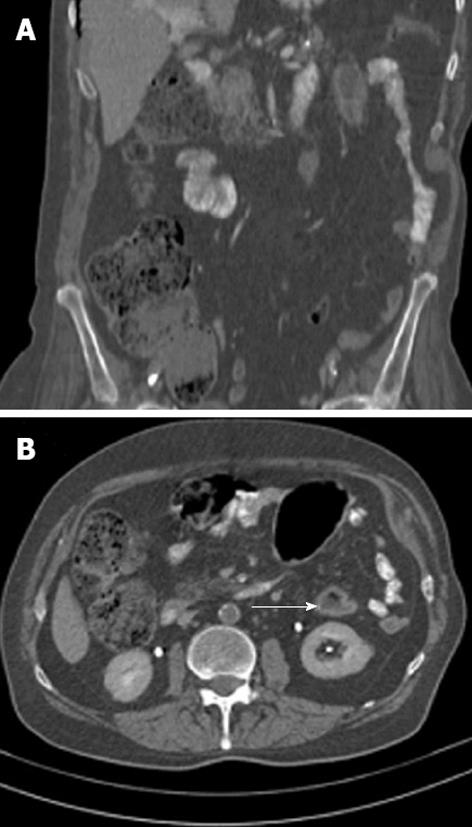

A contrast-enhanced CT scan (Figure 2) revealed segmental colitis involving the splenic flexure and the descending colon. The wall of the colon was markedly thickened with homogeneous enhancement and sharp definition, and it had a “dry” appearance. Concentric layers of low and high attenuation of the colonic wall (“double halo” sign) could be observed on sagittal sections, which suggested colonic edema. A long and narrow area of axial stenosis was present just below the splenic flexure. The stenosis extended to the distal third of the descending colon. Cecal and right colic distension were also observed, but there were no pericolic streakiness or fluid collections.

Figure 2 Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography scans suggesting segmental colitis involving the splenic flexure and the descending colon.

A: Coronal sections with zones of mural thickening of the colon just below the splenic flexure and a long and narrow axial stenosis of the descending colon; B: Sagittal sections showing (arrow) the "double halo" sign, a tomographic equivalent of the classic “thumbprinting” that is observed in barium enemas.

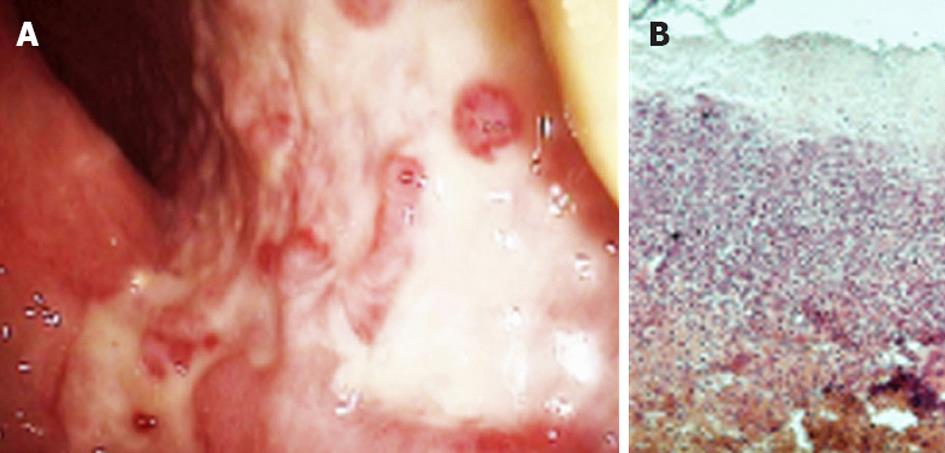

A colonoscopy found segmental edematous and hemorrhagic areas of the colonic mucosa surrounding large and deep ulcerations that were covered by pseudomembranes. When the pseudomembrane was washed off, the ulcerations revealed an erythematous and congestive granulation tissue. “Geographic”-like areas of mucosal denudation and “cobble stoning” were also observed (Figure 3A). The rectum was spared by an abrupt transition between normal and affected mucosa, and the ulcerative lesions extended to the sigmoid and descending colon. A narrow, long axial inflammatory stenosis was observed just below the splenic flexure. Biopsies showed edema, submucosal hemorrhage and necrotic areas, and an inflammatory infiltration with intravascular thrombi. The crypts had an atrophic appearance, but no cryptitis/cryptic abscesses or granulomas were observed (Figure 3B). Hemosiderin-laden macrophages were present in the mucosa and submucosa, and hyalinization and hemorrhages were observed in the lamina propria, which histologically confirmed ischemic colitis.

Figure 3 Morphologic changes confirming ischemic colitis by lower digestive endoscopy and histology.

A: Areas of mucosal ulceration, pseudomembranes and subsequent granulation observed at colonoscopy; B: Biopsy specimens from affected areas showing submucosal necrosis, inflammatory infiltration, cryptal atrophy and hyalinization. Hematoxylin-eosin staining, ×100. Courtesy Dr. Simionescu.

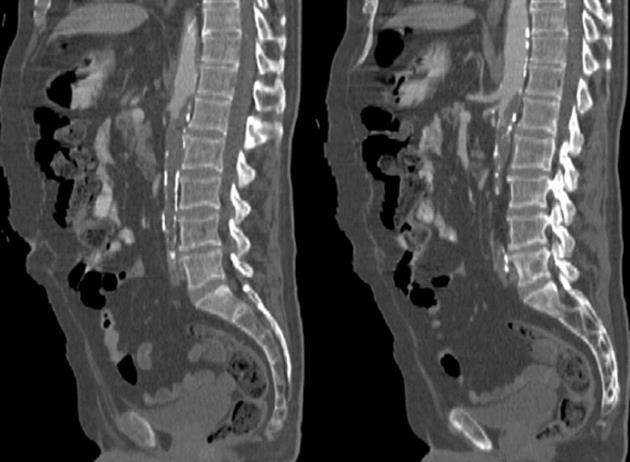

The therapeutic decision was to pursue a conservative treatment. After one week of bowel rest, fluid replacement, broad spectrum antibiotics and parenteral nutrition, the patient recovered well and was discharged. Six months later, in November 2011, the patient returned to the emergency room with acute abdominal pain, sudden evacuation of his bowel contents, abdominal distention, fever, vomiting and gross hematochezia. Abdominal tenderness, rebound and guarding occurred rapidly with tachycardia, polypnea and hypotension. A CT scan showed a huge thrombus in the abdominal aorta, which extended below the first lumbar vertebra and occluded more than 95% of the aortic lumen (Figure 4). The thrombosis spared the emergence of the celiac trunk and the upper mesenteric artery and appeared to completely occlude the origin of the inferior mesenteric; in the clinical context, this outcome suggested an intestinal infarction. An emergency laparotomy was performed in the following hours. The laparotomy showed a segmental infarction of the descending and sigmoid colon with a transmural hemorrhage and necrosis. Similar lesions were identified at the hepatic flexure. The attached mesentery was also hemorrhagic, and marked colic distention was observed. A total colectomy with ileostomy was successfully performed per primam, but unfortunately, the patient was lost in the following days after sepsis and cardiovascular complications.

Figure 4 Calcification of the abdominal aorta with extensive thrombosis inside, which completely obstructed the lumen below the 2nd lumbar vertebra.

Note that the celiac trunk and upper mesenteric artery are spared, whereas the lower mesenteric is completely occluded.

DISCUSSION

This instructive case presented several clinical aspects of atherothrombotic disease of the mesenteric territory. Most surveys do not include mesenteric ischemia among the major clinical consequences of atherosclerosis, especially considering that coronary and cerebrovascular events with peripheral arterial disease may be credited with 60%-75% of the clinical manifestations of the disease[8-10]. However, even if mesenteric ischemia is not listed in those studies, there is a significant degree of overlap, as 41% of patients present symptoms of the disease in two or more vascular beds[11]. Moreover, recent research[12] found a higher incidence than was preliminarily reported[13,14], increasing the estimate of hospitalizations to 16.4/100 000. Multi-vascular disease is encountered in 24% of cases, and comorbidities, such as hypertension (72%), diabetes (21%) and coronary artery disease (21%), frequently occur[12]. This observation is consistent with our case. In addition to mesenteric arterial thrombosis and embolization, other medical conditions can cause bowel ischemia, such as mesenteric venous thrombosis, trauma, small vessel disease (i.e., diabetes mellitus, vasculitis, amyloidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, radiation), hematologic disorders (i.e., protein C/S or antithrombin III deficiency, sickle cell disease), shock, medications (i.e., digitalis, diuretics, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), catecholamines, estrogens, danazol, neuroleptics), colonic obstruction, cocaine abuse or long-distance running[15]. In our case, iterative mesentero-aortic thrombosis was the primary cause of the clinical manifestations of the ischemic bowel disease that was encountered in our patient; however, other secondary factors, such as diabetic vasculopathy and even chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[16], should not be overlooked.

Clinical patterns of mesenteric ischemia may be either acute (“gangrenous”) or chronic (“nongangrenous”) forms[15,17]. Nongangrenous forms (80%-85%) are typically transient and reversible but can progress to chronic and irreversible strictures (10%-15%) or chronic segmental colitis (20%-25%). Acute forms[18] have four major causes: sudden complete arterial occlusion by emboli (50%), thrombosis of atherosclerotic stenosis (20%), small vessel occlusion (20%) and venous thrombosis (10%). Whereas embolic occlusion of the mesenteric arteries is typically brutal and dramatic, often presenting the hallmark “pain out of proportion with physical findings”, acute thrombosis of a stenotic atherosclerotic lesion may have a more insidious onset, and there may be a history of intestinal angina, which was the case in our patient. It is important not to miss the clinical signs of chronic mesenteric ischemia in a vascular patient, and it is also important to use angiography to aggressively evaluate the arterial damage in the mesenteric territory. Following the individual patient’s anatomic and comorbidity considerations, early revascularization with percutaneous angioplasty/stenting or open repair may prevent a worse outcome, although protocols are not yet fully standardized, and symptomatic recurrences that require reinterventions occur as frequently as 20% of the time[19].

Chronic nongangrenous colonic ischemia, which is frequently expressed by ischemic colitis, indicates a higher degree of impairment of the intestinal blood flow and, as a consequence, more severe vascular damage. The colon is particularly susceptible to hypoperfusion, and low-flow states often precipitate to preexisting mesenteric microvascular atherosclerosis. “Watershed areas”, such as the splenic flexure (Griffith’s point), ileocecal junction and rectosigmoid, are specific localizations of ischemic lesions, but diffuse and extended ischemic injury of the entire bowel can also be encountered[20]. Ischemia is segmental and superficial, and it only extends to the mucosa and submucosa (“partial mural ischemia”)[20,21]. The subsequent inflammation and fibrosis that follow this decrease in the blood supply lead to a “true” colitis that includes edema, neutrophil afflux and hyalinization. Ghost cells and hemosiderin-laden macrophages are highly specific findings that can facilitate diagnosis; these findings should be differentiated from other entities, such as infectious colitis (i.e., Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, E. coli O157:H7, Clostridium difficile), inflammatory bowel disease, medication-induced colitis (i.e., NSAIDs, hormones, anticoagulants, diuretics, antibiotics), malignancy, fecal impaction with stercoral ulcer, systemic disorders and amyloidosis[22]. Although therapy classically relies on conservative treatment and anticoagulation, the recurrence of disease, especially in high-risk vascular patients, can impose angiographic evaluation and revascularization procedures that may have beneficial outcomes despite an absence of standardized protocols[22,23].

In conclusion, ischemic bowel disease may be an expression of systemic atherosclerosis, especially in patients who have cumulative risk factors, such as dyslipidemia, diabetes or smoking, and a multi-vascular atherothrombotic pathology. These patients occasionally present all of the clinical forms of mesenteric ischemia, including intestinal angina, ischemic colitis and intestinal infarction. The symptoms may develop over several years and may be intricate, so their recognition is important. Simple anticoagulation does not always prevent major incidents, and revascularization procedures, such as percutaneous angioplasty or stenting, may ensure a better prognosis. In patients with ischemic bowel disease, the important lesson is to always consider aggressive investigations and therapeutic decisions while taking into account the associated benefits and risks. Angiographic evaluation and revascularization procedures are associated with beneficial outcomes despite an absence of standardized protocols. Current advances in endovascular therapy, such as percutaneous transluminal angioplasty with stenting, should be increasingly used in patients with chronic mesenteric ischemia. These procedures will limit the risks that are associated with open repair. However, technical difficulties, such as undistensible stenotic lesions, frequently occur.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Giuseppe Chiarioni, Gastroenterological Rehabilitation Division of the University of Verona, Valeggio sul Mincio Hospital, Azienda Ospedale di Valeggio s/M, 37067 Valeggio s/M, Italy

S- Editor Lv S L- Editor A E- Editor Lu YJ