Published online Oct 21, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i39.5595

Revised: September 10, 2012

Accepted: September 19, 2012

Published online: October 21, 2012

AIM: To evaluate the surgical outcomes following radical antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy (RAMPS) for pancreatic cancer.

METHODS: Twenty-four patients underwent RAMPS with curative intent between January 2005 and June 2009 at the National Cancer Center, South Korea. Clinicopathologic data, including age, sex, operative findings, pathologic results, adjuvant therapy, postoperative clinical course and follow-up data were retrospectively collected and analyzed for this study.

RESULTS: Twenty-one patients (87.5%) underwent distal pancreatectomy and 3 patients (12.5%) underwent total pancreatectomy using RAMPS. Nine patients (37.5%) underwent combined vessel resection, including 8 superior mesenteric-portal vein resections and 1 celiac axis resection. Two patients (8.3%) underwent combined resection of other organs, including the colon, stomach or duodenum. Negative tangential margins were achieved in 22 patients (91.7%). The mean tumor diameter for all patients was 4.09 ± 2.15 cm. The 2 patients with positive margins had a mean diameter of 7.25 cm. The mean number of retrieved lymph nodes was 20.92 ± 11.24 and the node positivity rate was 70.8%. The median survival of the 24 patients was 18.23 ± 6.02 mo. Patients with negative margins had a median survival of 21.80 ± 5.30 mo and those with positive margins had a median survival of 6.47 mo (P = 0.021). Nine patients (37.5%) had postoperative complications, but there were no postoperative mortalities. Pancreatic fistula occurred in 4 patients (16.7%): 2 patients had a grade A fistula and 2 had a grade B fistula. On univariate analysis, histologic grade, positive tangential margin, pancreatic fistula and adjuvant therapy were significant prognostic factors for survival.

CONCLUSION: RAMPS is a feasible procedure for achieving negative tangential margins in patients with carcinoma of the body and tail of the pancreas.

- Citation: Chang YR, Han SS, Park SJ, Lee SD, Yoo TS, Kim YK, Kim TH, Woo SM, Lee WJ, Hong EK. Surgical outcome of pancreatic cancer using radical antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy procedure. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(39): 5595-5600

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i39/5595.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i39.5595

Distal pancreatectomy, originally described at the Mayo Clinic in 1913, has been the standard procedure for carcinoma of the body or tail of the pancreas[1]. This traditional approach is, however, associated with a high tangential margin positive rate and is not based on the physiologic lymphatic drainage of the pancreas[2]. So far, there has been little progress in overcoming these shortcomings. Radical antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy (RAMPS), which was first introduced by Strasberg et al[3] in 2003 as a surgical treatment for carcinomas of the body and tail of the pancreas, is known as a feasible procedure for achieving a higher rate of negative tangential margins than the traditional approach. RAMPS is performed in a right-to-left fashion after early ligation of blood vessels, whereas pancreatosplenectomy is performed in a left-to-right fashion. In fact, RAMPS improves the tangential margin negative rate and provides better surgical exposure, especially in obese patients[3].

Strasberg et al[2] reported that negative tangential margins were obtained in 91% of all patients and that the 5-year overall survival rate was 26%. However, there have been few studies on the clinical outcomes following RAMPS[4]. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the surgical outcomes following RAMPS for carcinoma of the body and tail of the pancreas.

Twenty-four patients underwent RAMPS with curative intent between January 2005 and June 2009 at the National Cancer Center in South Korea. History-taking, physical examination, liver function tests, tumor marker (carbohydrate antigen 19-9) levels, and abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans were used for diagnostic and staging workup. A whole-body positron emission tomography scan was added when necessary. Clinicopathologic data, including age, sex, operative findings, pathologic results, adjuvant therapy, postoperative clinical course and follow-up data were collected and analyzed retrospectively. A pancreatic fistula after surgery was defined based on the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula definition[5]: a drain output of any measurable volume on or after postoperative day 3 with an amylase concentration greater than 3 times the serum amylase concentration. Postoperative complications were reviewed and graded using the Clavien-Dindo classification[6].

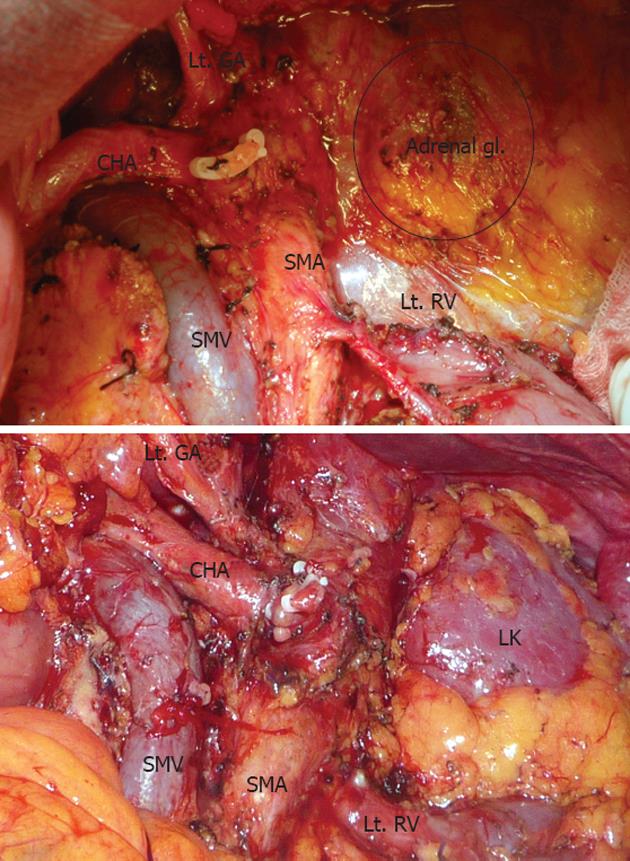

The operation was performed according to the procedure introduced by Strasberg et al[2]. After dissection of the gastro-colic ligament, we entered the lesser omentum and dissected the celiac axis, hepatic artery, and trunk of the splenic artery to divide the splenic artery. The neck of the pancreas was divided using electrocautery, and the pancreatic duct stump was ligated. After we divided the neck of the pancreas, the vertical plane of dissection reached the level of the aorta where the left renal vein was exposed. The left adrenal vein was ligated and divided when a posterior RAMPS was performed. During lymph node dissection, we removed regional nodes along the common hepatic and celiac artery. The soft tissue to the left of the hepatoduodenal ligament and superior mesenteric artery was also dissected. Lymph nodes along the splenic artery and splenic hilum were removed en-bloc with the specimen. Removal of the nerve plexus and lymph nodes was performed in the same manner (Figure 1).

We performed adjuvant concurrent chemoradiation therapy (CCRT) on all patients without severe medical comorbidities or poor physical status. Several studies have demonstrated the positive effects of CCRT[7-17]. Twenty patients (83.3%) underwent adjuvant CCRT using multiple-field techniques. The initial irradiated field, which was defined as the tumor bed plus regional nodes, received 45 Gy in 25 fractions using a 4-field technique (anteroposterior, posteroanterior and paired laterals) with 15-MV X-rays. The tumor bed boost field received an additional 5.4-10.8 Gy in 3 to 6 fractions of 1.8 Gy. Concomitant 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy during radiotherapy was given to all patients. Patients were followed every 3 mo with CT scans and tumor marker levels to detect recurrent disease.

The χ2 test, the independent t test, the Kaplan-Meier method with the log-rank test and a Cox regression model were used for statistical analysis. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. SPSS® version 19.0 (Chicago, IL, United States) was used for all statistical analyses. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Center in South Korea.

The mean age of the total 24 patients was 60.00 ± 7.79 years with a male:female ratio of 1.18:1. The mean operative time was 305.42 ± 155.68 min. One patient required a blood transfusion during surgery. Three patients (12.5%) who had cancer in the body of the pancreas with diffuse infiltration into the head and tail were converted to a total pancreatectomy. Nine patients (37.5%) underwent combined vessel resection, including 8 superior mesenteric-portal vein (SMV-PV) resections and 1 celiac axis resection. Two patients (8.3%) underwent combined resection of other organs, including the colon, stomach or jejunum. Posterior RAMPS, including resection of the adrenal gland, was performed in 5 patients (20.8%).

Histopathologic examination showed that 21 cases (87.5%) were T3. As for histologic grade, moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma was found in 17 patients (70.8%). The mean number of retrieved lymph nodes was 20.92 ± 11.24 and node positivity was observed in 17 patients (70.8%). The pancreatic parenchymal resection margin was negative for all patients with a mean distance of 16.52 ± 13.8 mm. Negative tangential margins were obtained in 22 patients (91.7%). The mean tumor diameter of all patients was 4.09 ± 2.15 cm. Two patients with positive tangential margins had a mean tumor diameter of 7.3 cm (Table 1). Among 9 patients with combined vessel resection, 1 patient had no evidence of vascular invasion on pathology.

| Parameters | n (%) |

| Mean tumor diameter | 4.09 ± 2.15 cm |

| Tumor diameter in negative margin (n = 22) | 3.80 ± 1.73 cm |

| Tumor diameter in positive margin (n = 2) | 7.25 cm |

| Histologic grade | |

| Well-differentiated | 2 (8.3) |

| Moderately-differentiated | 17 (70.8) |

| Poorly-differentiated | 5 (20.8) |

| T stage | |

| T2 | 3 (12.5) |

| T3 | 21 (87.5) |

| Lymph node metastasis | |

| (+) | 17 (70.8) |

| (-) | 7 (29.2) |

| Vascular invasion | |

| (+) | 12 (50) |

| (-) | 12 (50) |

| Lymphatic invasion | |

| (+) | 15 (62.5) |

| (-) | 9 (37.5) |

| Perineural invasion | |

| (+) | 21 (87.5) |

| (-) | 3 (12.5) |

| Tangential margin | |

| (+) | 2 (8.3) |

| (-) | 22 (91.7) |

Nine patients (37.5%) had postoperative complications (Table 2). Pancreatic fistula occurred in 4 patients (16.7%): 2 patients had a grade A fistula and 2 had a grade B fistula. Intra-abdominal fluid collections and grade B pancreatic fistulae were treated with percutaneous drainage and intravenous antibiotics. Patients with PV-SMV thrombosis were treated with percutaneous thrombectomy and stenting. There were no postoperative mortalities.

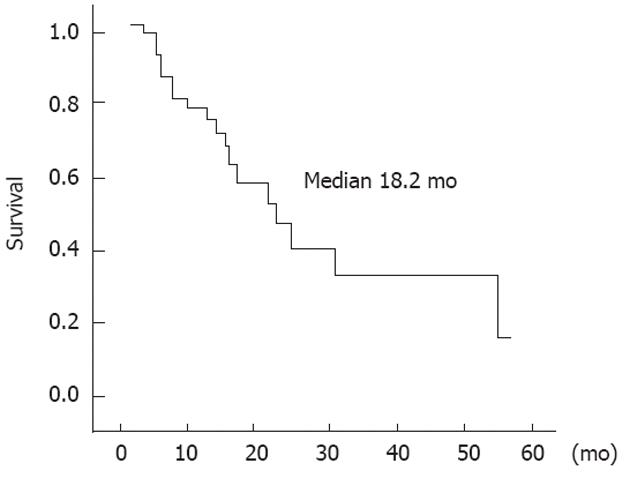

In this study, the median survival was 18.23 ± 6.02 mo with a median follow-up period of 20.06 ± 14.46 mo (Figure 2). Twenty-one patients (87.5%) had recurrence at follow-up. Two patients (8.3%) had local recurrence, 14 patients (58.3%) had distant metastasis, and 5 patients (20.8%) had both.

Celiac axis resection (Appleby operation) was performed in 1 patient who died of recurrent disease 12.5 mo after surgery. Three patients who underwent total pancreatectomy had a median survival of 21.23 ± 4.25 mo which was similar to the median survival of all patients in this study. One patient was free of cancer at his last visit, while the other 2 patients had local or systemic recurrence.

Twenty patients (83.3%) underwent adjuvant CCRT. CCRT was also performed in patients with pancreatic fistula with the exception of 1 patient with grade A pancreatic fistula who was not a candidate because of age.

On univariate analysis, histologic grade, positive tangential margin, pancreatic fistula and adjuvant therapy were significant prognostic factors for survival (Table 3). Unfortunately, this study was not powered to show significant factors on multivariate analysis.

| Factors | n | Median survival (mo) | P value | |

| Age | ≤ 60 yr | 11 | 21.84 ± 12.90 | 0.249 |

| > 60 yr | 13 | 16.93 ± 8.54 | ||

| Gender | Male | 13 | 21.80 ± 6.84 | 0.995 |

| Female | 11 | 18.23 ± 4.77 | ||

| Transfusion | (+) | 1 | 26.1 | 0.345 |

| (-) | 23 | 19.79 ± 14.73 | ||

| Operative time | ≤ 300 min | 18 | 21.80 ± 7.42 | 0.534 |

| > 300 min | 6 | 12.53 ± 6.96 | ||

| Type of RAMPS | Anterior | 19 | 21.80 ± 4.34 | 0.421 |

| Posterior | 5 | 12.53 ± 6.65 | ||

| Combined vascular resection | (+) | 9 | 16.93 ± 5.48 | 0.333 |

| (-) | 15 | 26.27 ± 10.81 | ||

| Tumor size | ≤ 4 cm | 15 | 26.27 ± 9.44 | 0.862 |

| > 4 cm | 9 | 18.23 ± 4.91 | ||

| Histologic grade | WD | 2 | 16.93 | 0.001 |

| MD | 17 | 26.27 ± 5.87 | ||

| PD | 5 | 6.46 ± 1.06 | ||

| T-stage | 2 | 3 | 21.17 ± 10.94 | 0.448 |

| 3 | 21 | 18.23 ± 5.79 | ||

| N-stage | 0 | 7 | 21.80 ± 16.32 | 0.485 |

| 1 | 17 | 18.23 ± 4.70 | ||

| Tangential margin | (+) | 2 | 6.46 | 0.031 |

| (-) | 22 | 21.80 ± 5.30 | ||

| Complication | (+) | 9 | 12.53 ± 4.77 | 0.385 |

| (-) | 15 | 21.80 ± 4.05 | ||

| Pancreatic fistula | (+) | 4 | 6.46 ± 1.52 | 0.003 |

| (-) | 20 | 26.27 ± 6.49 | ||

| Adjuvant therapy | (+) | 20 | 26.27 ± 6.49 | < 0.001 |

| (-) | 4 | 6.30 ± 0.48 |

Because carcinomas of the body and tail of the pancreas are often found in a larger size than those of the head, unresectable cases are more common and the recurrence rate after resection is also higher[18-22]. The goals of pancreatic cancer surgery are to obtain tumor-free margins and perform a sufficient regional lymphadenectomy. However, conventional distal pancreatectomy, which is performed in the left-to-right direction along the anterior border of Gerota’s facia, is inappropriate for achieving this goal because the tumor easily infiltrates the retroperitoneum and spreads to lymph nodes at an early stage. There have been few surgical methods to overcome these limitations. Yang et al[23] introduced retrograde distal pancreatectomy, which cuts the neck of the pancreas first and proceeds with dissection in the right-to-left direction. This procedure is a useful method for exposing the portal-superior mesenteric vein junction, which helps to avoid operative injuries. RAMPS was introduced with the theoretical advantages of obtaining a higher rate of negative tangential margins and a higher lymph node count. Therefore, we applied RAMPS to all distal pancreatectomy cases.

The margin-negative rate of RAMPS reported by Strasberg et al[2] and our institute was 91% and 91.7%, respectively, which is higher than the margin-negative rate of conventional distal pancreatectomy (70% to 80%)[5,7,8]. In our study, only 2 patients showed positive resection margins. These 2 patients had a lower median survival than patients with negative margins (6.47 mo vs 21.80 ± 5.30 mo, P = 0.03). The first patient with a positive tangential margin underwent posterior RAMPS and was stage T3N1 with a tumor size of 10.5 cm. He received adjuvant CCRT after recovering from grade B pancreatic fistula, but had multiple liver metastases at follow-up and survived 6.5 mo. The second patient underwent anterior RAMPS with combined jejunal resection due to gross invasion. He had stage T3N0 disease with a tumor size of 4.0 cm. He had both local recurrence and distant metastasis after adjuvant CCRT and survived 19.0 mo.

RAMPS has also been applied to laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy because it provides good surgical exposure for performing a right-to-left distal pancreatectomy. Kang et al[24] and Choi et al[25] reported outcomes of laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy performed on well-selected patients with left-sided pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas.

In a previous study performed by Strasberg et al[2], the mean number of retrieved lymph nodes and lymph node positivity rate were 14.3 and 48%, respectively. In our study, the mean number of retrieved lymph nodes was 20.92 ± 11.24 and the lymph node positivity rate was 70.8%. Lymph node status is known to be a very important prognostic factor in pancreatic cancer. Some previous reports emphasized the lymph node ratio (the number of positive lymph nodes/the total number of retrieved lymph nodes) in pancreatic cancer[26]. However, few studies have mentioned the number of retrieved lymph nodes, which makes it difficult to compare the surgical efficacy of RAMPS with conventional distal pancreatectomy.

Strasberg et al[2] reported that the median survival time and the 5-year survival rate after RAMPS were 21 mo and 26%, respectively, which were better than those of previous reports[18]. It is known that patients with left-sided pancreatic cancer have poorer survival rates than patients with right-sided pancreatic cancer. However, surgical outcomes for patients with left-sided cancer were better than those with right-sided pancreatic cancer. Our patients had a median survival of 18.23 ± 6.02 mo, which was a little better than the survival following distal pancreatectomy reported by previous studies of conventional distal pancreatectomy. However, our patients were mostly T3 or higher (87.5%), and lymph node positivity was 70.8%, which means that most of our patients were advanced stage. When viewed in this light, our results are better than those reported by previous studies and are comparable with those of right-sided pancreatic cancer.

We had 19 patients (79.2%) with systemic recurrence. Therefore, even though RAMPS has surgical advantages in terms of local control, there are limitations in preventing cancer progression, especially through systemic recurrence.

We performed distal pancreatectomy for carcinomas of the body and tail of the pancreas using RAMPS, with a negative tangential margin of 91.7%, no mortality and acceptable morbidity. It is suggested that RAMPS is a safe and feasible procedure for carcinomas of the body and tail of the pancreas. Further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to confirm our results.

Radical antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy (RAMPS) is known as a feasible procedure for achieving a higher rate of negative tangential margins than the traditional approach. Although RAMPS is widely performed, there have been few studies on its clinical outcomes.

This study provides reference data for future larger studies.

RAMPS was first introduced in 2003 as a surgical treatment for carcinomas of the body and tail of the pancreas.

RAMPS seems to be a feasible procedure for achieving negative tangential margins for patients with carcinoma of the body and tail of the pancreas.

| 1. | Andrén-Sandberg A, Wagner M, Tihanyi T, Löfgren P, Friess H. Technical aspects of left-sided pancreatic resection for cancer. Dig Surg. 1999;16:305-312. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Strasberg SM, Linehan DC, Hawkins WG. Radical antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy procedure for adenocarcinoma of the body and tail of the pancreas: ability to obtain negative tangential margins. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:244-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Strasberg SM, Drebin JA, Linehan D. Radical antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy. Surgery. 2003;133:521-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mitchem JB, Hamilton N, Gao F, Hawkins WG, Linehan DC, Strasberg SM. Long-term results of resection of adenocarcinoma of the body and tail of the pancreas using radical antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy procedure. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:46-52. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3282] [Cited by in RCA: 3554] [Article Influence: 169.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 6. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18532] [Cited by in RCA: 26126] [Article Influence: 1187.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Klinkenbijl JH, Jeekel J, Sahmoud T, van Pel R, Couvreur ML, Veenhof CH, Arnaud JP, Gonzalez DG, de Wit LT, Hennipman A. Adjuvant radiotherapy and 5-fluorouracil after curative resection of cancer of the pancreas and periampullary region: phase III trial of the EORTC gastrointestinal tract cancer cooperative group. Ann Surg. 1999;230:776-782; discussion 782-784. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Spitz FR, Abbruzzese JL, Lee JE, Pisters PW, Lowy AM, Fenoglio CJ, Cleary KR, Janjan NA, Goswitz MS, Rich TA. Preoperative and postoperative chemoradiation strategies in patients treated with pancreaticoduodenectomy for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:928-937. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Van Laethem JL, Hammel P, Mornex F, Azria D, Van Tienhoven G, Vergauwe P, Peeters M, Polus M, Praet M, Mauer M. Adjuvant gemcitabine alone versus gemcitabine-based chemoradiotherapy after curative resection for pancreatic cancer: a randomized EORTC-40013-22012/FFCD-9203/GERCOR phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4450-4456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yeo CJ, Abrams RA, Grochow LB, Sohn TA, Ord SE, Hruban RH, Zahurak ML, Dooley WC, Coleman J, Sauter PK. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: postoperative adjuvant chemoradiation improves survival. A prospective, single-institution experience. Ann Surg. 1997;225:621-633; discussion 633-636. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Further evidence of effective adjuvant combined radiation and chemotherapy following curative resection of pancreatic cancer. Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group. Cancer. 1987;59:2006-2010. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, Gellert K, Langrehr J, Ridwelski K, Schramm H, Fahlke J, Zuelke C, Burkart C. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297:267-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1779] [Cited by in RCA: 1791] [Article Influence: 94.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Koniaris L, Kaushal S, Abrams RA, Sauter PK, Coleman J, Hruban RH, Lillemoe KD. Resected adenocarcinoma of the pancreas-616 patients: results, outcomes, and prognostic indicators. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:567-579. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Dunn JA, Almond J, Beger HG, Pederzoli P, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fernandez-Cruz L, Lacaine F. Influence of resection margins on survival for patients with pancreatic cancer treated by adjuvant chemoradiation and/or chemotherapy in the ESPAC-1 randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2001;234:758-768. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Burris HA, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML, Modiano MR, Cripps MC, Portenoy RK, Storniolo AM, Tarassoff P. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2403-2413. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Regine WF, Winter KA, Abrams RA, Safran H, Hoffman JP, Konski A, Benson AB, Macdonald JS, Kudrimoti MR, Fromm ML. Fluorouracil vs gemcitabine chemotherapy before and after fluorouracil-based chemoradiation following resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1019-1026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 576] [Cited by in RCA: 550] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Regine WF, Winter KA, Abrams R, Safran H, Hoffman JP, Konski A, Benson AB, Macdonald JS, Rich TA, Willett CG. Fluorouracil-based chemoradiation with either gemcitabine or fluorouracil chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: 5-year analysis of the U.S. Intergroup/RTOG 9704 phase III trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1319-1326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Christein JD, Kendrick ML, Iqbal CW, Nagorney DM, Farnell MB. Distal pancreatectomy for resectable adenocarcinoma of the body and tail of the pancreas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:922-927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kimura W, Han I, Furukawa Y, Sunami E, Futakawa N, Inoue T, Shinkai H, Zhao B, Muto T, Makuuchi M. Appleby operation for carcinoma of the body and tail of the pancreas. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44:387-393. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Shimada K, Sakamoto Y, Sano T, Kosuge T. Prognostic factors after distal pancreatectomy with extended lymphadenectomy for invasive pancreatic adenocarcinoma of the body and tail. Surgery. 2006;139:288-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Shoup M, Conlon KC, Klimstra D, Brennan MF. Is extended resection for adenocarcinoma of the body or tail of the pancreas justified? J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:946-952; discussion 952. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Brennan MF, Moccia RD, Klimstra D. Management of adenocarcinoma of the body and tail of the pancreas. Ann Surg. 1996;223:506-511; discussion 511-512. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Yang Y, Ge CL, Guo KJ, Guo RX, Tian YL. Application of retrograde distal pancreatectomy. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2008;7:318-321. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Kang CM, Kim DH, Lee WJ. Ten years of experience with resection of left-sided pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: evolution and initial experience to a laparoscopic approach. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1533-1541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Choi SH, Kang CM, Lee WJ, Chi HS. Multimedia article. Laparoscopic modified anterior RAMPS in well-selected left-sided pancreatic cancer: technical feasibility and interim results. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2360-2361. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Riediger H, Keck T, Wellner U, zur Hausen A, Adam U, Hopt UT, Makowiec F. The lymph node ratio is the strongest prognostic factor after resection of pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1337-1344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Peer reviewer: Hiroki Yamaue, MD, Professor and Chairman, Second Department ofSurgery, Wakayama Medical University School of Medicine, 811-1 Kimiidera, Wakayama 641-8510, Japan

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY