Published online Oct 7, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i37.5289

Revised: May 10, 2012

Accepted: May 13, 2012

Published online: October 7, 2012

AIM: To report our experience using mini-laparotomy for the resection of rectal cancer using the total mesorectal excision (TME) technique.

METHODS: Consecutive patients with rectal cancer who underwent anal-colorectal surgery at the authors’ hospital between March 2001 and June 2009 were included. In total, 1415 patients were included in the study. The cases were divided into two surgical procedure groups (traditional open laparotomy or mini-laparotomy). The mini-laparotomy group was defined as having an incision length ≤ 12 cm. Every patient underwent the TME technique with a standard operation performed by the same clinical team. The multimodal preoperative evaluation system and postoperative fast track were used. To assess the short-term outcomes, data on the postoperative complications and recovery functions of these cases were collected and analysed. The study included a plan for patient follow-up, to obtain the long-term outcomes related to 5-year survival and local recurrence.

RESULTS: The mini-laparotomy group had 410 patients, and 1015 cases underwent traditional laparotomy. There were no differences in baseline characteristics between the two surgical procedure groups. The overall 5-year survival rate was not different between the mini-laparotomy and traditional laparotomy groups (80.6% vs 79.4%, P = 0.333), nor was the 5-year local recurrence (1.4% vs 1.5%, P = 0.544). However, 1-year mortality was decreased in the mini-laparotomy group compared with the traditional laparotomy group (0% vs 4.2%, P < 0.0001). Overall 1-year survival rates were 100% for Stage I, 98.4% for Stage II, 97.1% for Stage III, and 86.6% for Stage IV. Local recurrence did not differ between the surgical groups at 1 or 5 years. Local recurrence at 1 year was 0.5% (2 cases) for mini-laparotomy and 0.5% (5 cases) for traditional laparotomy (P = 0.670). Local recurrence at 5 years was 1.5% (6 cases) for mini-laparotomy and 1.4% (14 cases) for traditional laparotomy (P = 0.544). Days to first ambulation (3.2 ± 0.8 d vs 3.9 ± 2.3 d, P = 0.000) and passing of gas (3.5 ± 1.1 d vs 4.3 ± 1.8 d, P = 0.000), length of hospital stay (6.4 ± 1.5 d vs 9.7 ± 2.2 d, P = 0.000), anastomotic leakage (0.5% vs 4.8%, P = 0.000), and intestinal obstruction (2.2% vs 7.3%, P = 0.000) were decreased in the mini-laparotomy group compared with the traditional laparotomy group. The results for other postoperative recovery function indicators, such as days to oral feeding and defecation, were similar, as were the results for immediate postoperative complications, including the physiologic and operative severity score for the enumeration of mortality and morbidity score.

CONCLUSION: Mini-laparotomy, as conducted in a single-centre series with experienced TME surgeons, is a safe and effective new approach for minimally invasive rectal cancer surgery. Further evaluation is required to evaluate the use of this approach in a larger patient sample and by other surgical teams.

- Citation: Wang XD, Huang MJ, Yang CH, Li K, Li L. Minilaparotomy to rectal cancer has higher overall survival rate and earlier short-term recovery. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(37): 5289-5294

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i37/5289.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i37.5289

Laparoscopic surgery has become popular throughout the world[1-3]. This surgical method enhances early postoperative recovery with less pain, less analgesic use, an earlier return of gastrointestinal function, and fewer wound and pulmonary complications. Total mesorectal excision (TME) is acknowledged worldwide as the preferred technique for surgical resection of rectal cancer[4-6]. Multiple studies have reported marked reductions in local recurrence with the TME technique, including single-centre, multiple-centre, and population studies[7,8]. The laparoscopic approach to TME resection of rectal cancer is currently being evaluated in multicentre randomised trials[9-12].

A less-recognised surgical technique aimed at improving postoperative recovery is mini-laparotomy. With this technique, surgical dissection is performed under direct vision, as in open surgery; laparoscopic equipment and training is not required. Early experience with mini-laparotomy has been reported from a few medical centres in case series of colon and rectal resection[13-15]. Mini-laparotomy has been developed as a techniques based on the advanced recognition of more information about pelvic anatomy and the dissection of subtle perirectal structures in laparotomy[16,17].

In view of these circumstances, our surgical centre has performed mini-laparotomies for rectal cancer for approximately 8 years. The aim of this study is to report our experience using mini-laparotomy for the resection of rectal cancer using the TME technique. Furthermore, we aim to compare the oncologic findings and the postoperative recovery indexes of mini-laparotomy and traditional laparotomy, thus providing more evidence to help surgeons select an operating procedure.

This study is registered as an International Clinical Trial (ChiCTR-TRC-09000618) to compare TME resection of rectal cancer using traditional open laparotomy vs mini-laparotomy. This is a retrospective analysis of consecutive patients with rectal cancer observed at the Anal-colorectal Surgery Ward in West China Hospital of Sichuan University between March 2001 and June 2009. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) diagnosis of rectal cancer; (2) no previous history of lower abdominal operations or pelvic operations; (3) possibility of curative resection; and (4) intestinal continuity was restored by anastomosis. The exclusion criteria were (1) curative resection was not achieved; (2) resections without anastomosis (APR and Hartmann); and (3) actively exciting the study. All of the enrolled patients provided informed consent, which included information about (1) the different kinds of treatment available for their cancer; (2) the benefit of different operation procedures; and (3) their doctor’s recommendation. Ultimately, the choice of surgical technique was left to the patient. The database from the anal-colorectal surgery of West China Hospital in Sichuan University provided the research data[18]. If any data required for the study were missing, the patient was excluded. Most of the patients who were excluded for this reason were missing data related to pathology and surgical baselines; 5-year survival and local recurrence; and the first time of aerofluxus, defecation, ambulation, oral feeding during the recovery phase. Ultimately, 1415 patients were included in the study.

A multimodal preoperative evaluation system was used to assess the preoperative clinical cancer stage[19]. Clinical Stages III and IV patients were treated with neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy consisting of FOLFOX-4 (Oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2 ivgtt 2 h, 1 d; LV 200 mg/m2 ivgtt 2 h, 1-2 d; 5-Fu 400 mg/m2iv, 1-2 d). Perioperative radiation is not used at our centre.

Surgery was performed by traditional open laparotomy as the standard procedure. Mini-laparotomy was performed on an ad-hoc basis, with increasing frequency in the latter years of this study. No patient within the mini-laparotomy group was converted to a traditional laparotomy.

Short-term perioperative data were obtained in all cases. Long-term follow-up data were available from 7 to 103 mo. The follow-up methods used included telephone follow-up, outpatient department follow-up and follow-up letters. Follow-up data were obtained in 96.3% of cases (1362/1415).

TME and pelvic autonomic nerve preservation were performed in all cases in accordance with the Colorectal Surgery Guideline of West China Hospital of Sichuan University[20]. The surgery and perioperative management were performed by the same clinical team for both the traditional open laparotomy and mini-laparotomy groups.

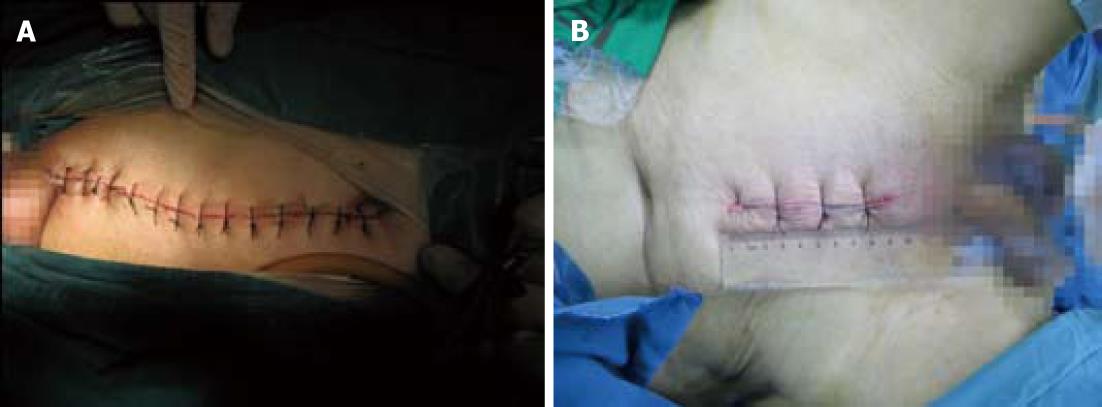

A vertical incision was used for all cases. The traditional laparotomy incision extended from the pubis to above the umbilicus with a length of 13 to 18 cm, as in Figure 1. The mini-laparotomy incision extended from the pubis for a length of 12 cm or less. For the traditional laparotomy, a fixed self-retaining retractor was used on the incision, and a moveable curved retractor was used for dynamic exposure during dissection. In mini-laparotomy, two curved retractors were used in dynamic exposure during dissection without a fixed abdominal wound retractor. Dissection was performed using electrocautery and an ultrasonic knife in both open laparotomy and mini-laparotomy. In both mini-laparotomy and traditional laparotomy, the splenic flexure was not mobilised. The superior rectal artery was ligated just below the bifurcation of the inferior mesenteric artery with clearing of the superior rectal artery lymph nodes.

A post-operative fast-track protocol was used[21,22] with early ambulation. Discharge criteria included eating a normal diet, normal ambulation, no fever, and no postoperative complications.

The primary outcome variables are 5-year survival and local recurrence. Local recurrence was classified as intro-/peri-anastomotic and pelvic recurrence. Secondary outcomes are immediate postoperative complications, including physiologic and operative severity score for the enumeration of mortality and morbidity (POSSUM) score[23], and recovery functions (the time of the first aerofluxus, defecation, ambulation, and oral feeding during the recovery phase). In addition, the patients’ postoperative complications were recorded as important information about secondary outcomes, which included gastric retention, incision infection, pulmonary infection, anastomosis leakage, and intestinal obstruction.

The mini-laparotomy and traditional laparotomy data were compared and analysed with t tests, and the count data used the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact probability test. Local recurrence and overall survival were assessed using Kaplan-Meier survival curve analysis. The data are expressed as means ± SD. The significance level was 0.05. Statistical tests were performed using SPSS 15.0.

The characteristics of the 1415 included patients (410 mini-laparotomy cases and 1005 traditional laparotomy cases) are presented in Table 1. There were no significant difference in the baseline data for the two groups (P > 0.05). The surgical and pathological findings are presented in Table 2, and there were no significant differences between the two surgical groups (P > 0.05).

| Minilaparotomy (n = 410) | Traditional laparotomy (n = 1005) | P value | |

| Gender | 0.125 | ||

| Male | 273 (66.6) | 635 (63.2) | |

| Female | 137 (33.4) | 370 (36.8) | |

| Age (yr) | 61.2 ± 12.1 | 57.8 ± 12.4 | 0.385 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.3 ± 3.0 | 22.0 ± 2.9 | 0.331 |

| Distance to dentate line (cm) | 8.2 ± 3.2 | 7.2 ± 4.0 | 0.118 |

| Minilaparotomy | Traditional laparotomy | P value | |

| TNM stage | 0.838 | ||

| Stage I | 47 (11.5) | 119 (11.8) | |

| Stage II | 127 (31.0) | 320 (31.8) | |

| Stage III | 151 (36.8) | 379 (37.7) | |

| Stage IV | 85 (20.7) | 187 (18.6) | |

| Differentiation | 0.579 | ||

| Good | 105 (25.6) | 240 (23.9) | |

| Moderate | 172 (42.0) | 411 (40.9) | |

| Poor | 133 (32.4) | 354 (35.2) | |

| Histologic types | 0.277 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 337 | 811 | |

| Mucinous adenocacinoma | 69 | 164 | |

| Squamous carcinoma | 4 | 30 | |

| Operation types | 0.640 | ||

| High anterior resection | 20 (4.9) | 38 (3.8) | |

| Low anterior resection | 124 (30.2) | 284 (28.3) | |

| Ultralow anterior resection | 189 (46.1) | 482 (48.0) | |

| Colo-anal anastomosis | 77 (18.8) | 201 (20.0) | |

| Volume of bleeding (mL) | 78.5 ± 30.0 | 80.8 ± 28.5 | 0.940 |

| Operation time (min) | 115.5 ± 35.8 | 114.6 ± 33.4 | 0.217 |

| Lymph node counts | 12.4 | 12.7 | 0.796 |

| Proximal margin of distance (cm) | 3.5 | 3.3 | 0.105 |

| Distal margin of distance (cm) | 7.0 | 6.9 | 0.780 |

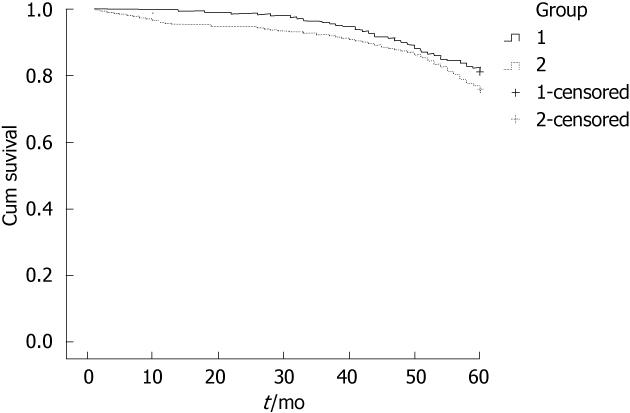

Overall 5-year survival did not differ between the mini-laparotomy and traditional laparotomy groups (80.6% vs 79.4%, P = 0.333; Figure 2). The 5-year survival rates for the different clinical stages were also similar. One-year mortality was decreased in the mini-laparotomy group compared to the traditional laparotomy group (0% vs 4.2%, P < 0.0001). The overall 1-year survival rates in the traditional group were 100% for Stage I, 98.4% for Stage II, 97.1% for Stage III, and 86.6% for Stage IV. Local recurrence did note differ between surgical groups at 1 or 5 years. Local recurrence at 1 year was 0.5% (2 cases) for the mini-laparotomy group and 0.5% (5 cases) for the traditional laparotomy group (P = 0.670). Local recurrence at 5 years was 1.5% (6 cases) for the mini-laparotomy group and 1.4% (14 cases) for the traditional laparotomy group (P = 0.544).

The data regarding postoperative recovery functions (time of first aerofluxus, defecation, ambulation and oral feeding), length of hospital stay, and immediate postoperative complications, including POSSUM score, are shown in Table 3. Days to first ambulation and aerofluxus and hospital length of stay were reduced for the mini-laparotomy group compared with the traditional laparotomy group. Days to tolerating full oral diet and first defecation were similar between surgical groups. POSSUM scores predicting mortality and morbidity were not different between the surgical groups.

| Minilaparotomy group | Traditional laparotomy group | P value | |

| Recovery | |||

| Aerofluxus (d) | 3.5 ± 1.1 | 4.3 ± 1.8 | 0.000 |

| Oral feeding (d) | 4.1 ± 1.2 | 4.6 ± 1.2 | 0.628 |

| Defecation (d) | 5.0 ± 1.4 | 5.4 ± 1.5 | 0.370 |

| Ambulation (d) | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 3.9 ± 2.3 | 0.000 |

| Hospital stay (d) | 6.4 ± 1.5 | 9.7 ± 2.2 | 0.000 |

| POSSUM scores (%) | |||

| Predictive mortality | 28.1 | 26.8 | 0.738 |

| Predictive morbidity | 5.3 | 5.0 | 0.844 |

| Complications | |||

| Gastric retention | 8 (2.0) | 18 (1.8) | 0.494 |

| Incision infection | 6 (1.5) | 15 (1.5) | 0.592 |

| Pulmonary infection | 5 (1.2) | 14 (1.4) | 0.513 |

| Anastomosis leakage | 2 (0.5) | 48 (4.8) | 0.000 |

| Intestinal obstruction | 9 (2.2) | 73 (7.3) | 0.000 |

| Other | 13 (3.2) | 35 (3.5) | 0.456 |

Gastric retention and wound and pulmonary infection were not different between the surgical groups. Anastomotic leakage and intestinal obstruction were decreased in the mini-laparotomy group compared with the traditional laparotomy group. Other postoperative complications, including urinary retention (2 cases vs 6 cases), urinary tract infection (0 case vs 2 cases), anastomotic bleeding (1 case vs 2 cases), intra-abdominal haemorrhage (0 case vs 1 case), wound dehiscence (1 case vs 2 cases), sexual dysfunction (1 case vs 3 cases), deep vein thrombosis (0 case vs 0 case), cardiocerebral vascular accident (0 case vs 0 case), psychosis (2 cases vs 4 cases), liver dysfunction (1 case vs 2 cases), and unknown fever (5 cases vs 13 cases) also did not differ between the two surgical groups.

The overall 5-year survival and local recurrence rates were not different between the mini-laparotomy and traditional laparotomy groups. The local recurrence and survival rates for mini-laparotomy (1.4% and 79.7%) compare favourably to those reported for traditional laparotomy, as shown in Table 4.

In our study, the results confirmed that the mini-laparotomy and traditional laparotomy groups had similar overall 5-year survival and local recurrence rates, but the minilaparotomy group experienced faster postoperative recovery and fewer complications. It may be that minilaparotomy surgery is the safer and more effective operation for rectal cancer.

An improved understanding of pelvic anatomy has enabled the switch to a mini-laparotomy approach to rectal cancer resection. Whereas others have reported on the use of mini-laparotomy mostly for colon cancer, we are among the first to report on the use of mini-laparotomy for the resection of rectal cancer[8,9,12]. There is a learning curve for the mini-laparotomy approach. However, we speculate that the learning curve is lower than that of laparoscopic proctectomy because standard instrumentation, direct vision and tactile feedback are maintained for mini-laparotomy, but not for laparoscopy. We have used mini-laparotomy for rectal resection in Chinese patients with a body mass index (BMI) of 21.3 kg/m2 as the Chinese population is generally thinner than North American and European populations[24]; however, we also treat patients with BMIs > 27 using mini-laparotomy. Additionally, although splenic flexure mobilisation was not required for any patient in this sample, it is likely that the surgeon would be disadvantaged by the suprapubic mini-laparotomy approach if splenic flexure mobilisation was required to perform a low tension-free anastomosis. Mini-laparotomy was not associated with an increase in operative blood loss or operation time. In fact, mini-laparotomy was associated with the successful resection of all levels of rectal cancer.

Like laparoscopic colorectal resection[25], mini-laparotomy showed advantages in decreasing the postoperative length of hospital stay and was associated with shorter times to ambulation and aerofluxus[1,11]. Mini-laparotomy was associated with significantly decreased anastomotic leaking, a finding for which we have no ready explanation other than increased experience over the time of the study. The anastomotic leak rate of 0.5% compares favourably to that reported in other studies[26-28]. In addition, mini-laparotomy was associated with decreased postoperative intestinal obstruction, which may have resulted from less peritoneal manipulation and a shorter incision length. A Japanese study suggested that the mini-laparotomy approach in colorectal cancer would result in a reduced inflammatory response[29]. Furthermore, mortality at 1 year was significantly increased in the traditional laparotomy group compared with the mini-laparotomy group.

Although postoperative management was intended to be similar for mini-laparotomy and traditional laparotomy patients, as indicated by the time before achieving a full oral diet and defecation, traditional laparotomy patients were slower to ambulate. Bias in favour of the mini-laparotomy group is likely, as this procedure has gained favour in our hands with our increasing experience over the time of this study. A randomised study design is indicated to minimise this bias. The study was a single-centre series with experienced TME surgeons and a patient sample with a relatively small BMI. Because our hospital is a medical centre in southwestern China, our patients are primarily advanced cancer cases, and we have more experienced surgeons and more advanced surgical instruments than other small-to-medium sized local hospitals. Consequently, the study and results had an obvious selection bias. Further evaluation is required to evaluate the use of this approach in a larger patient sample and by other surgical teams, and our conclusions are not definitive.

In conclusion, we have shown that mini-laparotomy is a safe and effective new approach for minimally invasive rectal cancer surgery. This was a single-centre series with experienced TME surgeons and a patient sample with a relatively low BMI. Further evaluation is required to evaluate the use of this approach in a larger patient sample and by other surgical teams.

We thank Dr. Tian-Fang Zeng, Dr. Chang-Long Qin and Dr. Liu-Qun Jia for their language and data processing support in the preparation of this manuscript.

Total mesorectal excision (TME) is acknowledged worldwide as the preferred technique for surgical resection of rectal cancer. The laparoscopic approach to TME resection of rectal cancer is currently being evaluated in multicentre randomised trials. A less-recognised surgical technique aimed at improving postoperative recovery is mini-laparotomy. With this technique, surgical dissection is performed under direct vision, as in open surgery; laparoscopic equipment and training is not required. Early experience with mini-laparotomy has been reported from a few medical centres in case series of colon and rectal resection. Mini-laparotomy has been developed as a techniques based on the advanced recognition of more information about pelvic anatomy and the dissection of subtle perirectal structures in laparotomy.

An improved understanding of pelvic anatomy has enabled the switch to a mini-laparotomy approach to rectal cancer resection. Other studies have reported on the use of mini-laparotomy mostly for colon cancer, but for rectal cancer, it is still in blank. Like laparoscopic colorectal resection, mini-laparotomy showed advantages in decreasing the postoperative length of hospital stay and was associated with shorter times to ambulation and aerofluxus in past studies

Whereas others have reported on the use of mini-laparotomy mostly for colon cancer, the authors are among the first to report on the use of mini-laparotomy for the resection of rectal cancer. There is a learning curve for the mini-laparotomy approach. However, the authors speculate that the learning curve is lower than that of laparoscopic proctectomy because standard instrumentation, direct vision and tactile feedback are maintained for mini-laparotomy, but not for laparoscopy. Mini-laparotomy was associated with significantly decreased anastomotic leaking, a finding for which the authors have no ready explanation other than increased experience over the time of the study. The anastomotic leak rate of 0.5% compares favourably to that reported in other studies. In addition, mini-laparotomy was associated with decreased postoperative intestinal obstruction, which may have resulted from less peritoneal manipulation and a shorter incision length. Furthermore, mortality at 1 year was significantly increased in the traditional laparotomy group compared with the mini-laparotomy group.

The study results suggest that mini-laparotomy is a safe and effective new approach for minimally invasive rectal cancer surgery.

Minilaparotomy is minimal invasive laparotomy for abdominal operations. It is different from laparoscopic operations, that minilaparotomy will have only one mini-incision, but not other holes from laparoscopic way. Minilaparotomy would be more better outcomes than traditional laparotomy.

This is a good descriptive study conducted in a single-centre series with experienced TME surgeons, and mini-laparotomy is proved a safe and effective new approach for minimally invasive rectal cancer surgery. Minilaparotomy will be the future choice for rectal cancer care.

| 1. | Inomata M, Yasuda K, Shiraishi N, Kitano S. Clinical evidences of laparoscopic versus open surgery for colorectal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2009;39:471-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pendlimari R, Holubar SD, Pattan-Arun J, Larson DW, Dozois EJ, Pemberton JH, Cima RR. Hand-assisted laparoscopic colon and rectal cancer surgery: feasibility, short-term, and oncological outcomes. Surgery. 2010;148:378-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Veldkamp R, Kuhry E, Hop WC, Jeekel J, Kazemier G, Bonjer HJ, Haglind E, Påhlman L, Cuesta MA, Msika S. Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: short-term outcomes of a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:477-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2360] [Cited by in RCA: 2325] [Article Influence: 110.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Leroy J, Jamali F, Forbes L, Smith M, Rubino F, Mutter D, Marescaux J. Laparoscopic total mesorectal excision (TME) for rectal cancer surgery: long-term outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:281-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 291] [Cited by in RCA: 283] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Park JS, Choi GS, Jun SH, Hasegawa S, Sakai Y. Laparoscopic versus open intersphincteric resection and coloanal anastomosis for low rectal cancer: intermediate-term oncologic outcomes. Ann Surg. 2011;254:941-946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lacy AM, Adelsdorfer C. Totally transrectal endoscopic total mesorectal excision (TME). Colorectal Dis. 2011;13 Suppl 7:43-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jung B, Påhlman L, Johansson R, Nilsson E. Rectal cancer treatment and outcome in the elderly: an audit based on the Swedish Rectal Cancer Registry 1995-2004. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kapiteijn E, Kranenbarg EK, Steup WH, Taat CW, Rutten HJ, Wiggers T, van Krieken JH, Hermans J, Leer JW, van de Velde CJ. Total mesorectal excision (TME) with or without preoperative radiotherapy in the treatment of primary rectal cancer. Prospective randomised trial with standard operative and histopathological techniques. Dutch ColoRectal Cancer Group. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:410-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Baik SH, Gincherman M, Mutch MG, Birnbaum EH, Fleshman JW. Laparoscopic vs open resection for patients with rectal cancer: comparison of perioperative outcomes and long-term survival. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:6-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lujan J, Valero G, Hernandez Q, Sanchez A, Frutos MD, Parrilla P. Randomized clinical trial comparing laparoscopic and open surgery in patients with rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2009;96:982-989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 300] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rajput A, Bullard Dunn K. Surgical management of rectal cancer. Semin Oncol. 2007;34:241-249. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Bleday R, Wong WD. Recent advances in surgery for colon and rectal cancer. Curr Probl Cancer. 1993;17:1-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cima RR, Pattana-arun J, Larson DW, Dozois EJ, Wolff BG, Pemberton JH. Experience with 969 minimal access colectomies: the role of hand-assisted laparoscopy in expanding minimally invasive surgery for complex colectomies. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:946-950; discussion 950-952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pasupathy S, Eu KW, Ho YH, Seow-Choen F. A comparison between open versus laparoscopic assisted colonic pouches for rectal cancer. Tech Coloproctol. 2001;5:19-22. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Kam MH, Seow-Choen F, Peng XH, Eu KW, Tang CL, Heah SM, Ooi BS. Minilaparotomy left iliac fossa skin crease incision vs. midline incision for left-sided colorectal cancer. Tech Coloproctol. 2004;8:85-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ishida H, Nakada H, Yokoyama M, Hayashi Y, Ohsawa T, Inokuma S, Hoshino T, Hashimoto D. Minilaparotomy approach for colonic cancer: initial experience of 54 cases. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:316-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Takegami K, Kawaguchi Y, Nakayama H, Kubota Y, Nagawa H. Minilaparotomy approach to colon cancer. Surg Today. 2003;33:414-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lv DH, Wang XD, Yang CH, Cao L, Li L. Early database construction of multidisciplinary team in colorectal cancer. Zhongguo Putong Waike Zazhi. 2007;14:713-715. |

| 19. | Wang X, Lv D, Song H, Deng L, Gao Q, Wu J, Shi Y, Li L. Multimodal preoperative evaluation system in surgical decision making for rectal cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25:351-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Li L, Wang XD, Shu Y, Wang YY, Wang C, Wang ZQ, Wang TC, Zhou ZG. [Clinical Practices in Anal-colorectal Surgery in West China Hospital of Sichuan University]. Jiezhichang Gangmen Waike. 2009;15:4-9. |

| 21. | Li L, Wang XD, Shu Y, Yu YY, Wang C, Wang ZQ, Wang TC, Zhou ZG. [Fast Track Guideline for Colorectal Surgery of West China Hospital in Sichuan University(1)]. Zhongguo Puwai Jichu Yu Linchuang Zazhi. 2009;16:413. |

| 22. | Schwenk W, Neudecker J, Raue W, Haase O, Müller JM. "Fast-track" rehabilitation after rectal cancer resection. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:547-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Richards CH, Leitch FE, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. A systematic review of POSSUM and its related models as predictors of post-operative mortality and morbidity in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1511-1520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | de Munter JS, Agyemang C, van Valkengoed IG, Bhopal R, Stronks K. Sex difference in blood pressure among South Asian diaspora in Europe and North America and the role of BMI: a meta-analysis. J Hum Hypertens. 2011;25:407-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lindsetmo RO, Champagne B, Delaney CP. Laparoscopic rectal resections and fast-track surgery: what can be expected? Am J Surg. 2009;197:408-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Brown SR, Eu KW, Seow-Choen F. Consecutive series of laparoscopic-assisted vs. minilaparotomy restorative proctocolectomies. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:397-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kim JS, Cho SY, Min BS, Kim NK. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after laparoscopic intracorporeal colorectal anastomosis with a double stapling technique. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209:694-701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Akasu T, Takawa M, Yamamoto S, Yamaguchi T, Fujita S, Moriya Y. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage following intersphincteric resection for very low rectal adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:104-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Nakagoe T, Tsuji T, Sawai T, Sugawara K, Inokuchi N, Kamihira S, Arisawa K. Minilaparotomy may be independently associated with reduction in inflammatory responses after resection for colorectal cancer. Eur Surg Res. 2003;35:477-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Andreoni B, Chiappa A, Bertani E, Bellomi M, Orecchia R, Zampino M, Fazio N, Venturino M, Orsi F, Sonzogni A. Surgical outcomes for colon and rectal cancer over a decade: results from a consecutive monocentric experience in 902 unselected patients. World J Surg Oncol. 2007;5:73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Law WL, Poon JT, Fan JK, Lo OS. Survival following laparoscopic versus open resection for colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:1077-1085. [PubMed] |

Peer reviewers: San-Jun Cai, MD, Professor, Director, Department of Colorectal Surgery, Cancer Hospital, Fudan University, 270 Dong An Road, Shanghai 200032, China; Francis Seow-Choen, MBBS, FRCSEd, FAMS, Professor, Seow-Choen Colorectal Centre, Mt Elizabeth Medical Centre, 3 Mt Elizabeth Medical Centre No. 09-10, Singapore 228510, Singapore

S- Editor Lv S L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L