Published online Aug 28, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i32.4357

Revised: July 23, 2012

Accepted: July 28, 2012

Published online: August 28, 2012

AIM: To determine which features of history and demographics predict a diagnosis of malignancy or peptic stricture in patients presenting with dysphagia.

METHODS: A prospective case-control study of 2000 consecutive referrals (1031 female, age range: 17-103 years) to a rapid access service for dysphagia, based in a teaching hospital within the United Kingdom, over 7 years. The service consists of a nurse-led telephone triage followed by investigation (barium swallow or gastroscopy), if appropriate, within 2 wk. Logistic regression analysis of demographic and clinical variables was performed. This includes age, sex, duration of dysphagia, whether to liquids or solids, and whether there are associated features (reflux, odynophagia, weight loss, regurgitation). We determined odds ratio (OR) for these variables for the diagnoses of malignancy and peptic stricture. We determined the value of the Edinburgh Dysphagia Score (EDS) in predicting cancer in our cohort. Multivariate logistic regression was performed and P < 0.05 considered significant. The local ethics committee confirmed ethics approval was not required (audit).

RESULTS: The commonest diagnosis is gastro-esophageal reflux disease (41.3%). Malignancy (11.0%) and peptic stricture (10.0%) were also relatively common. Malignancies were diagnosed by histology (97%) or on radiological criteria, either sequential barium swallows showing progression of disease or unequivocal evidence of malignancy on computed tomography. The majority of malignancies were esophago-gastric in origin but ear, nose and throat tumors, pancreatic cancer and extrinsic compression from lung or mediastinal metastatic cancer were also found. Malignancy was statistically more frequent in older patients (aged >73 years, OR 1.1-3.3, age < 60 years 6.5%, 60-73 years 11.2%, > 73 years 11.8%, P < 0.05), males (OR 2.2-4.8, males 14.5%, females 5.6%, P < 0.0005), short duration of dysphagia (≤ 8 wk, OR 4.5-20.7, 16.6%, 8-26 wk 14.5%, > 26 wk 2.5%, P < 0.0005), progressive symptoms (OR 1.3-2.6: progressive 14.8%, intermittent 9.3%, P < 0.001), with weight loss of ≥ 2 kg (OR 2.5-5.1, weight loss 22.1%, without weight loss 6.4%, P < 0.0005) and without reflux (OR 1.2-2.5, reflux 7.2%, no reflux 15.5%, P < 0.0005). The likelihood of malignancy was greater in those who described true dysphagia (food or drink sticking within 5 s of swallowing than those who did not (15.1% vs 5.2% respectively, P < 0.001). The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value of the EDS were 98.4%, 9.3%, 11.8% and 98.0% respectively. Three patients with an EDS of 3 (high risk EDS ≥ 3.5) had malignancy. Unlike the original validation cohort, there was no difference in likelihood of malignancy based on level of dysphagia (pharyngeal level dysphagia 11.9% vs mid sternal or lower sternal dysphagia 12.4%). Peptic stricture was statistically more frequent in those with longer duration of symptoms (> 6 mo, OR 1.2-2.9, ≤ 8 wk 9.8%, 8-26 wk 10.6%, > 26 wk 15.7%, P < 0.05) and over 60 s (OR 1.2-3.0, age < 60 years 6.2%, 60-73 years 10.2%, > 73 years 10.6%, P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION: Malignancy and peptic stricture are frequent findings in those referred with dysphagia. The predictive value for associated features could help determine need for fast track investigation whilst reducing service pressures.

- Citation: Murray IA, Palmer J, Waters C, Dalton HR. Predictive value of symptoms and demographics in diagnosing malignancy or peptic stricture. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(32): 4357-4362

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i32/4357.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i32.4357

Esophageal cancer accounts for 3% of all cancer diagnoses in the United Kingdom (an annual incidence of nearly 8000) and has poor prognosis[1-4]. The Department of Health in the United Kingdom has produced guidelines to identify patients with dyspepsia at higher risk of upper gastro-intestinal malignancy and requiring rapid referral and investigation[5]. Dysphagia is an alarm symptom with a high predictive value for finding significant pathology [odds ratio (OR) 2.0-3.1 for malignancy in 3600 referrals to a rapid access upper gastro-intestinal cancer service][6].

However, dysphagia is common, occurring in 5%-8% of those over 50[7]. It can be due to many different underlying conditions, including malignancy.

Many patients referred to secondary care with “dysphagia” do not actually have any swallowing difficulties[8]. Despite it being a relatively good predictive symptom for cancer diagnosis, even in those with true dysphagia, less than 10% have cancer[8]. Patients presenting with dysphagia require rapid assessment, diagnosis and treatment. An accurate diagnosis is dependent upon history and appropriate investigations, which may include barium swallow, gastroscopy or esophageal manometry[9-13].

If it were possible to predict which patient demographics and symptoms were most highly predictive of serious pathology, especially malignancy or peptic stricture and which predicted a non-serious problem, it would allow health resources to be targeted towards rapid investigation in the high risk group. A scoring system, the Edinburgh Dysphagia Score (EDS) has been devised to predict which patients require fast track investigations[14].

The aim of our study is to identify which factors are strongest predictors of malignancy or peptic stricture in patients referred to a rapid access service with dysphagia. We use our data to validate the EDS on a larger patient cohort.

The Royal Cornwall Hospital serves a largely rural population of 450 000, more than 99% of whom are white. The county is one of the poorest in the United Kingdom.

The dysphagia hotline (DHL) service consists of an initial telephone triage by our nurse endoscopist with barium swallow or endoscopy within one week. The radiology department hot report DHL barium swallow examinations and if the examination is abnormal, the patient is given diet Cola and metoclopramide and undergoes gastroscopy after 2 h[15].

We prospectively collect data on patient demographics and final diagnosis following gastroscopy or barium swallow based on test results and clinical opinion. Duration of dysphagia, whether for both liquids and solids, and whether there are associated features (reflux, odynophagia, weight loss, regurgitation) are all prospectively recorded. Review of demographics, patient presentation and final diagnosis showed highly predictive variables for each major diagnosis, so these were formally analysed.

The EDS was determined for each patient (determined by scores for age, weight loss (> 3 kg), duration of symptoms, sex, location of dysphagia and presence of acid reflux)[14].

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using IBM SPSS 19 software. The relationship between the variables and the diagnosis was explored using Pearson’s χ2 Independence test. The predictive value of each variable in diagnosing malignancy and in diagnosing peptic stricture was explored using logistic regression. In both analysis, a P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The South West Regional Ethics committee determined that formal ethics approval was not required as the study fell within the category of audit.

From April 2004 to January 2011, 2000 patients were referred, 48.5% male, age range 17-103 years, mean 68.1 years (SD 14.1 years). Of these, 225 (11.2%) did not undergo investigation through the dysphagia hotline, mainly because they refused any investigations but also because we were unable to contact them by telephone, or they were admitted prior to test. Two patients’ data could not be interpreted for clerical reasons. Three hundred and thirty-five patients (20% of those investigated) denied true dysphagia, defined as the feeling of food or drink sticking within 5 s of swallowing, the majority describing globus although some presented with dyspepsia or weight loss.

Of those having investigations, 259 (14.6%) had barium swallow only, 1341 (75.5%) gastroscopy only and 175 (9.9%) had both procedures. Twenty patients failed to attend an appointment for procedures (7 barium swallows, 9 gastroscopies, the remainder unspecified) giving a DNA (did not attend) rate of 1.1% for patients referred for procedures.

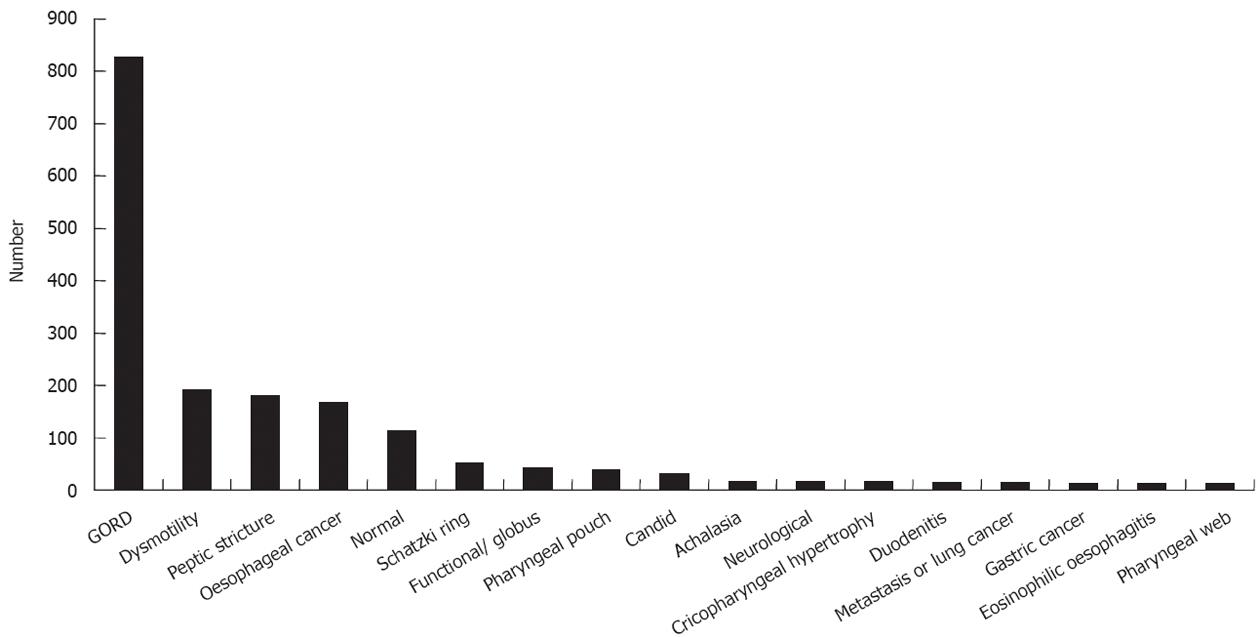

The most common diagnosis was gastro-esophageal reflux disease 826 (41.3%) with the more serious diagnoses of malignancy [199 (11.0%), 183 of gastrointestinal origin], peptic stricture 179 (10.0%), pharyngeal pouch 38 (2.1%) and achalasia 16 (0.9%). All outcomes are shown in Figure 1.

We investigated the likelihood of various significant pathologies based on patient demographics and presenting symptoms, including age (divided empirically into three similar sized groups of under 60 years, 60-73 years and over 73 years), sex, the type of dysphagia (to liquids, solids or both), whether the symptoms were progressive, whether “true dysphagia” or globus, and associated features including weight loss (defined as > 2 kg loss of weight in preceding 3 mo, the Department of Health criterion for a 2 wk wait referral), duration of dysphagia and presence or absence of reflux (percentages of each are shown on Table 1).

| Demographics | |||

| Age | < 60 yr | 60-73 yr | > 73 yr |

| 26.4 | 34.9 | 38.7 | |

| Sex | Male | Female | |

| 48.5 | 51.5 | ||

| Clinical features | |||

| Nature of dysphagia | Solids | Liquids | Both |

| 79.6 | 0.7 | 19.7 | |

| Symptoms progressive | Yes | No | |

| 40 | 60 | ||

| “True” dysphagia | Dysphagia | Globus | |

| 81.3 | 18.7 | ||

| Weight loss ≥ 2 kg in past 3 mo | Yes | No | |

| 28.5 | 71.5 | ||

| Presence of reflux | Yes | No | |

| 60.6 | 39.4 | ||

| Duration of dysphagia | < 8 wk | 8-26 wk | > 26 wk |

| 34.5 | 42 | 23.5 |

A diagnosis of malignancy or of peptic stricture was significantly associated with a history of true dysphagia (feeling of food or drink sticking within 5 s of swallowing) than in those who did not (P < 0.001).

Logistic regression was performed using the Enter method to assess the impact of a number of factors on the likelihood of someone presenting with dysphagia having malignancy. The model contained seven independent variables (sex, age, duration of symptoms, nutrition, progressive symptoms, reflux and weight loss) however, the type of dysphagia was found to be highly non-significant (P = 0.727) and so the model was run again with removal of this variable.

The strongest predictor of a cancer diagnosis was the duration of symptoms (Table 2). If a patient reported symptom duration of less than eight weeks, the OR of having cancer was 9.6 higher than for symptoms more than twenty six weeks (95% CI: 4.5-20.7). The OR was 6 (95% CI: 2.8-12.8) for symptom duration between eight and twenty six weeks. The next strongest predictor was the presence of weight loss greater than 2 kg where the OR of 3.6 (95% CI: 2.5-5.1). Being male increased the likelihood of malignancy 3.3 fold (95% CI: 2.2-4.8) compared to females. Being less than sixty years old reduced the likelihood of a cancer diagnosis by 47.1% compared to being over 73 (OR 0.53, 95% CI: 0.3-0.9). If the patient had reflux, the OR of 0.54 (95% CI: 0.4-0.8) showed the likelihood of malignancy was significantly reduced and if symptoms were progressive then the OR of a cancer diagnosis was 1.8 (95% CI: 1.3-2.6). The sensitivity and specificity values are 97.6% and 31.1% respectively.

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | Significance | ||

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Sex (male) | 3.358 | 2.273 | 4.961 | 0.000 |

| Progressive | 1.807 | 1.259 | 2.593 | 0.001 |

| Weight loss | ||||

| ≥ 2 kg | 3.572 | 2.501 | 5.104 | 0.000 |

| Reflux | 0.528 | 0.369 | 0.754 | 0.000 |

| Age | ||||

| < 60 yr | 0.529 | 0.320 | 0.872 | 0.013 |

| 60-73 yr | 1.170 | 0.788 | 1.737 | 0.437 |

| Duration | ||||

| < 8 wk | 11.019 | 4.897 | 24.794 | 0.000 |

| 8-26 wk | 6.936 | 3.124 | 15.398 | 0.000 |

Using an EDS > 3.5 (10) to predict likelihood of cancer gave sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values of 98.4%, 9.3%, 11.8% and 98.0%. The three cancer cases that did not fall into the high risk group as defined in the original paper, had an EDS of 3.

Of patients with pharyngeal level dysphagia, 11.9% had malignancy, compared to 12.4% of patients with dysphagia affecting mid or lower chest (P = NS), i.e., in our cohort, the level of dysphagia was not significant for a diagnosis of malignancy.

Logistic regression was also used to assess the impact of a number of factors on the likelihood of someone presenting with dysphagia of having peptic stricture. The model originally contained seven independent variables. However five of these variables were not statistically significant and therefore were removed from the model [reflux (P = 0.703), sex (P = 0.247), progressive symptoms (P = 0.196), type of dysphagia (P = 0.156) and weight loss (P = 0.069). The only significant factors were age (P = 0.012) and duration of symptoms (P = 0.008)].

The OR of having a peptic stricture diagnosis is reduced by 48.9% for patients under 60 years old (OR 0.51, 95% CI: 0.33-0.80), and by 24.5% for patients between 60-73 years old (OR 0.76, 95% CI: 0.52-1.1) compared to those older than 73 years. The OR of having a peptic stricture diagnosis is reduced by 47.9% in patients presenting with symptoms of duration less than 8 wk (0.52, 95% CI: 0.34-0.81) and 37% in patients with symptoms of duration of between 8-26 wk (0.63, 95% CI: 0.43-0.92) compared to patients with symptom duration greater than 26 wk. The sensitivity and specificity values were 95.2% and 8.1% respectively.

In summary, in patients presenting with dysphagia, the likelihood of a diagnosis of cancer is increased by being male, over the age of 60 years, experiencing weight loss of > 2 kg with progressive symptoms but without reflux and a symptom duration of less than eight weeks. Patients who have had their symptoms for greater than twenty six weeks and are over the age of 73 years are more likely to have a peptic stricture diagnosis than those presenting with the same symptoms that are younger and have symptoms for less than 26 wk.

For the past 7 years we have offered a telephone triage and one stop procedure service for dysphagia and have been referred 2000 patients. The commonest underlying cause for dysphagia is reflux disease but we have found malignancy in 10% of those referred and peptic stricture in 9%. We have prospectively collected data on patient demographics and symptoms at time of referral. Logistic regression analysis has enabled us to determine which symptoms and features make the diagnosis of malignancy or peptic stricture more likely.

Previous studies have found an incidence of cancer in 4%-15% of those referred with dysphagia[6,16-19] making this an alarm symptom with a relatively high positive predictive value. We have confirmed this and also shown that in those referred to the DHL without dysphagia, the likelihood of malignancy is considerably lower.

Malignancy is more common in older men with a shorter duration of symptoms (less than 8 wk), with weight loss and without associated reflux. The negative association with reflux and positive association with weight loss has been noted previously[8,14] as has the negative association with long duration of symptoms (greater than either 6 mo[14] or 1 year[8]). Because of the size of our cohort we have been able to demonstrate that those with particularly short duration of symptoms (less than 8 wk) have a markedly increased likelihood of malignancy (increased 11 fold) compared to those with symptoms from 8 wk to 6 mo (nearly 7 fold increase from those with symptoms of more than 6 mo).

Our findings are similar to those of Rhatigan et al[14] who have produced the “Edinburgh dysphagia score” to triage patients referred with dysphagia into low or high risk for malignancy. They have also found an increased likelihood of malignancy in patients who were male, older, with shorter duration of symptoms and have noted a negative association with symptoms of reflux. They found a significant relationship between type of dysphagia and the likelihood of cancer in univariate but not in multivariate analysis and hence they do not include it in their final calculation. In our study, the relationship was not statistically significant. Conventionally it is thought that dysphagia to solids is most likely due to organic obstruction whilst that to liquids is due to neuromuscular incoordination so it is interesting that both studies failed to demonstrate a significant relationship. It is possible in our own study that this was due to few patients having dysphagia to liquids alone.

There are several differences between their study and this one however. We failed to confirm a positive association of a malignant diagnosis with localisation of disease (in study of Rhatigan et al[14], dysphagia below the pharyngeal level was more likely to be associated with malignancy) or with progressive nature of symptoms (found to be an independent risk for malignancy but not included in their final scoring system). The reasons for this are not clear, although we did have 10 fold more patients with pharyngeal level dysphagia making it possible that the difference found previously had been a type 1 error due to a relatively small sample size. Alternatively there may be some unrecognised difference in referral patterns between the 2 hospitals.

We chose to group patients into three age ranges rather than investigating age as a continual variable but confirmed a strong association with older patients more likely to have malignancy and we chose 2 kg weight loss cut-off for weight loss as this is the weight chosen by the Department of Health in their guidelines for referral under the suspected cancer pathway. Only 8.4% of our patients fell into the low-risk group compared to 30.0% in study of Rhatigan et al[14]. This may have been because of the older age of our patients (mean age 68.1 years against 61.4 years in the original development cohort).

The high specificity and positive predictive value of the EDS was confirmed although again concerningly there were 3 patients who had malignancy but an EDS of less than 3.5. This figure is comparable to the study of Rhatigan et al[14] where the EDS failed to detect one malignancy in a cohort of 574 patients investigated, compared to 3 patients with malignancy in 1775 investigated. Clearly, whilst high risk patients with scores of 3.5 and above require urgent investigation, those with scores below this also require still to be investigated, albeit with a lower incidence of malignancy.

Further studies are required to determine whether the ORs are generalizable in other populations and in particular in non-whites. It would also be useful to record the effect of smoking and alcohol consumption on likelihood of both diagnoses.

As with malignancy, the likelihood of peptic stricture is greater in older patients but in contrast to a diagnosis of malignancy which is associated with a shorter duration of symptoms, a longer duration of symptoms (greater than 26 wk) is considered a feature of a peptic stricture diagnosis. No other clinical features were significantly associated with a diagnosis of peptic stricture. The associated with long duration of symptoms in older patients was recognized nearly 20 years ago but is worth re-iterating[20-22].

Interestingly type of dysphagia (to solids rather than liquids), was not significant for neither malignancy nor peptic stricture. It is recognized that a history of dysphagia to solids progressing to both solids and liquids is indicative of mechanical obstruction whereas dysphagia to both at the onset is likely to be functional in origin[23]. Relatively few of our patients had dysphagia to liquids only or both and we did not ask about the nature of the dysphagia at the onset which might explain this.

Likewise a history of reflux did not predict peptic stricture and appeared protective against a diagnosis of malignancy. Reflux is a known risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma and cardial tumors (OR 7.7 and 2.0 respectively[24]. In this and study of Rhatigan et al[14] it may simply have been more strongly associated with a final alternative diagnosis, namely reflux esophagitis[21].

Future studies could focus on other factors which are recognized as risk factors for esophageal malignancy such as alcohol intake and smoking[25-29] and this could improve the model of malignancy prediction.

We have prospectively obtained history from patients undergoing investigation for dysphagia and have demonstrated which factors are most likely to be indicative of malignancy or peptic stricture disease and hence which necessitate urgent investigation. We have confirmed the value of the EDS in recognising a smaller group of patients with dysphagia who require less urgent investigation.

Dysphagia can be the presenting symptom of a serious pathology, namely malignancy or peptic stricture. Determining which patients are more likely to have malignancy or stricture could help determine which patients need urgent investigation.

A previous study from Scotland has shown malignancy to be more common in older males, with short duration of progressive symptoms, no reflux, weight loss and dysphagia not at the pharyngeal level and produced the Edinburgh Dysphagia Score (EDS).

The authors investigated 1775 patients with dysphagia and confirmed earlier findings malignancy to be more common in older men with progressive symptoms of less than 8 wk duration and weight loss of at least 2 kg. Malignancy was more common in those without reflux but level of dysphagia did not predict malignancy. An EDS of less than three predicted no malignancy. Peptic stricture was more common in older patients with longer duration of symptoms.

The authors confirmed the value of the EDS but caution that a score of 3 may still predict malignancy (contrary to the original article). Authors also defined predictors of peptic stricture. Where resources are limited these predictors could be used to expedite investigations in high risk patients.

It is larger scale cohort of validation study for the EDS than ever before. EDS is useful for primarily diagnosing esophageal malignancy associated with dysphagia.

| 1. | Office for National Statistics. Cancer Statistics registrations: Registrations of cancer diagnosed in 2007, England. Series MB1 no.38. 2010; Available from: http: //www.qub.ac.uk/research-centres/nicr/CancerData/OnlineStatistics/Oesophagus/. (Accessed 18/07/12). |

| 3. | Northern Ireland Cancer Registry. Oesophagus. Incidence and survival, 1993-2010. Available from: http: //www.qub.ac.uk/research-centres/nicr/CancerData/OnlineStatistics/Oesophagus/. (Accessed 18/07/12). |

| 4. | Welsh Cancer Intelligence and Surveillance Unit. Cancer Incidence in Wales, 2009. Available from: http: //www.wales.nhs.uk/sites3/Documents/242/Cancer Incidence in Wales 2003-2007.pdf. (Accessed 17/07/12). |

| 5. | Department of Health. Guidance on commissioning cancer services: improving outcomes in upper gastro-intestinal cancers - the manual. London: Department of Health 2001; Available from: http: //pro.mountvernoncancernetwork.nhs.uk/assets/Uploads/documents/IOG-Upper-GI-Manual.pdf. (Accessed 17/07/12). |

| 6. | Kapoor N, Bassi A, Sturgess R, Bodger K. Predictive value of alarm features in a rapid access upper gastrointestinal cancer service. Gut. 2005;54:40-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Lindgren S, Janzon L. Prevalence of swallowing complaints and clinical findings among 50-79-year-old men and women in an urban population. Dysphagia. 1991;6:187-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Melleney EM, Subhani JM, Willoughby CP. Dysphagia referrals to a district general hospital gastroenterology unit: hard to swallow. Dysphagia. 2004;19:78-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cook AJ. Diagnostic evaluation of dysphagia. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5:393-403. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Spechler SJ. American gastroenterological association medical position statement on treatment of patients with dysphagia caused by benign disorders of the distal esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:229-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Varadarajulu S, Eloubeidi MA, Patel RS, Mulcahy HE, Barkun A, Jowell P, Libby E, Schutz S, Nickl NJ, Cotton PB. The yield and the predictors of esophageal pathology when upper endoscopy is used for the initial evaluation of dysphagia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:804-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Alaani A, Vengala S, Johnston MN. The role of barium swallow in the management of the globus pharyngeus. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264:1095-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Esfandyari T, Potter JW, Vaezi MF. Dysphagia: a cost analysis of the diagnostic approach. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2733-2737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rhatigan E, Tyrmpas I, Murray G, Plevris JN. Scoring system to identify patients at high risk of oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1831-1837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mitchell J, Farrow R, Hussaini SH, Dalton HR. Clearance of barium from the oesophagus with diet cola and metoclopramide: a one stop approach to patients with dysphagia. Clin Radiol. 2001;56:64-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Melleney EM, Willoughby CP. Audit of a nurse endoscopist based one stop dyspepsia clinic. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78:161-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Loehry JK, Smith TR, Vyas SK. Achieving the “two week standard” for suspected upper GI cancers: continuing pain with minimal gain: a retrospective audit. Gut. 2002;50:A100. |

| 18. | Lassman DJ, Elliott J, Taylor A, Green AT, Grimley CE. Service implications and success of the implementation of the two-week wait referral criteria for upper GI cancers in a district general hospital. Gut. 2002;50:A63. |

| 19. | Spahos T, Hindmarsh A, Cameron E, Tighe MR, Igali L, Pearson D, Rhodes M, Lewis MP. Endoscopy waiting times and impact of the two week wait scheme on diagnosis and outcome of upper gastrointestinal cancer. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:728-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Marks RD, Richter JE. Peptic strictures of the esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1160-1173. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Locke GR, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ. Can symptoms predict endoscopic findings in GERD? Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:661-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Richter JE. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in the older patient: presentation, treatment, and complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:368-373. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Castell DO, Donner MW. Evaluation of dysphagia: a careful history is crucial. Dysphagia. 1987;2:65-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lagergren J, Bergström R, Lindgren A, Nyrén O. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:825-831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2115] [Cited by in RCA: 2042] [Article Influence: 75.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Coleman HG, Bhat S, Johnston BT, McManus D, Gavin AT, Murray LJ. Tobacco smoking increases the risk of high-grade dysplasia and cancer among patients with Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:233-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Pelucchi C, Tramacere I, Boffetta P, Negri E, La Vecchia C. Alcohol consumption and cancer risk. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63:983-990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Islami F, Fedirko V, Tramacere I, Bagnardi V, Jenab M, Scotti L, Rota M, Corrao G, Garavello W, Schüz J. Alcohol drinking and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma with focus on light-drinkers and never-smokers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:2473-2484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Anantharaman D, Marron M, Lagiou P, Samoli E, Ahrens W, Pohlabeln H, Slamova A, Schejbalova M, Merletti F, Richiardi L. Population attributable risk of tobacco and alcohol for upper aerodigestive tract cancer. Oral Oncol. 2011;47:725-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wu M, Zhao JK, Zhang ZF, Han RQ, Yang J, Zhou JY, Wang XS, Zhang XF, Liu AM, van' t Veer P. Smoking and alcohol drinking increased the risk of esophageal cancer among Chinese men but not women in a high-risk population. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22:649-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Peer reviewer: Kenichi Goda, MD, PhD, Department of Endoscopy, The Jikei University School of Medicine, 3-25-8 Nishi-shimbashi, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-8461, Japan

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY