Published online Jul 28, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i28.3770

Revised: April 18, 2012

Accepted: April 22, 2012

Published online: July 28, 2012

A 75-year old man had been diagnosed at 42 years of age as having polycythemia vera and had been monitored at another hospital. Progression of anemia had been recognized at about age 70, and the patient was thus referred to our center in 2008 where secondary myelofibrosis was diagnosed based on bone marrow biopsy findings. Hematemesis due to rupture of esophageal varices occurred in January and February of 2011. The bleeding was stopped by endoscopic variceal ligation. Furthermore, in March of the same year, hematemesis recurred and the patient was transported to our center. He was in irreversible hemorrhagic shock and died. The autopsy showed severe bone marrow fibrosis with mainly argyrophilic fibers, an observation consistent with myelofibrosis. The liver weighed 1856 g the spleen 1572 g, indicating marked hepatosplenomegaly. The liver and spleen both showed extramedullary hemopoiesis. Myelofibrosis is often complicated by portal hypertension and is occasionally associated with gastrointestinal hemorrhage due to esophageal varices. A patient diagnosed as having myelofibrosis needs to be screened for esophageal/gastric varices. Myelofibrosis has a poor prognosis. Therefore, it is necessary to carefully decide the therapeutic strategy in consideration of the patient’s concomitant conditions, treatment invasiveness and quality of life.

- Citation: Tokai K, Miyatani H, Yoshida Y, Yamada S. Multiple esophageal variceal ruptures with massive ascites due to myelofibrosis-induced portal hypertension. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(28): 3770-3774

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i28/3770.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i28.3770

Myelofibrosis is a disease resulting in extensive diffuse fibrosis involving the bone marrow and is characterized by hepatosplenomegaly, leukoerythroblastosis and so on.

Portal hypertension reportedly occurs as a complication in 10%-17% of patients[1] and may be accompanied by gastroesophageal variceal hemorrhage[2]. Herein, we present a patient diagnosed with myelofibrosis who died 3 years later due to repeated ruptures of esophageal varices, associated with massive ascites. Autopsy findings of this case are described with a discussion of the relevant literature.

The patient was a 75-year-old man. Increases in 2 blood cell lines, white and red blood cells, had been detected by medical examination at age 42 years, and polycythemia vera was diagnosed at another hospital. Blood hemoglobin (Hb) at this time was approximately 19 g/dL. Thereafter, the patient had been monitored without treatment, but blood Hb gradually decreased from 2005 onward. Thus, the patient was referred to the Department of Hematology of our center in October 2009.

The white blood cell count was 29 700/μL, the red blood cell count 641 × 106/μL, showing an increase in 2 blood cell lines, and juvenile cells were noted (Table 1).

| Hematology | Blood chemistry | Coagulation | |||

| WBC | 29 700/μL | Na | 142 mEq/L | PT | 0.98 |

| BAND | 35.4% | K | 4.5 mEq/L | APTT | 32.9 s |

| SEG | 45% | Cl | 103 mEq/L | ||

| LYMP | 2.6% | BUN | 24 mg/dL | ||

| MONO | 1.4% | Cr | 0.8 mg/dL | Serology | |

| EOSI | 2.8% | AST | 26 IU/L | HBsAg | (-) |

| BASO | 4.2% | ALT | 25 IU/L | HBsAb | (-) |

| PRO | + | ALP | 599 IU/L | ||

| MYELO | 7.4% | LDH | 578 IU/L | ||

| META | 0.8% | γ-GTP | 65 IU/L | ||

| BLAST | 0.2% | T-Bil | 1.4 mg/dL | ||

| RBC | 641 × 1/μL | Amy | 28 IU/L | ||

| Hb | 14.2 g/dL | CK | 39 IU/L | ||

| Ht | 47.3% | TP | 6.3 g/dL | ||

| MCV | 73.8 fl | Alb | 4.1 g/dL | ||

| MCH | 22.2 pg | CRP | 1.36 mg/dL | ||

| MCHC | 30 g/dL | ||||

| Plt | 156 × 1/μL | ||||

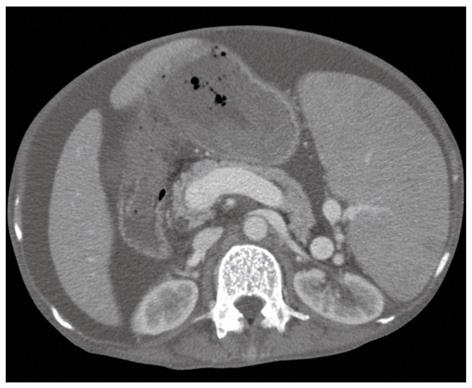

Abdominal computed tomography scan revealed a large quantity of ascites in the peritoneal cavity, and marked spleen enlargement and dilatation of the splenic vein were seen (Figure 1). There were no abnormalities of the liver or other organs. No obvious blood clot formation was seen in the main blood vessels.

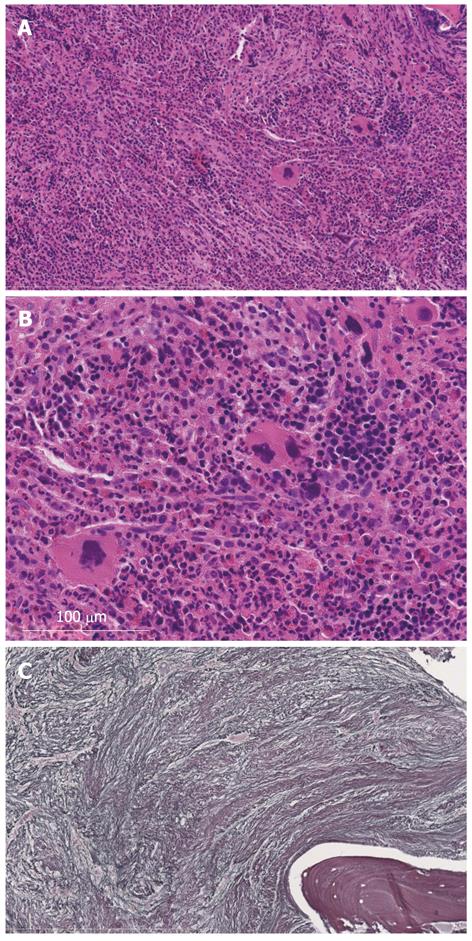

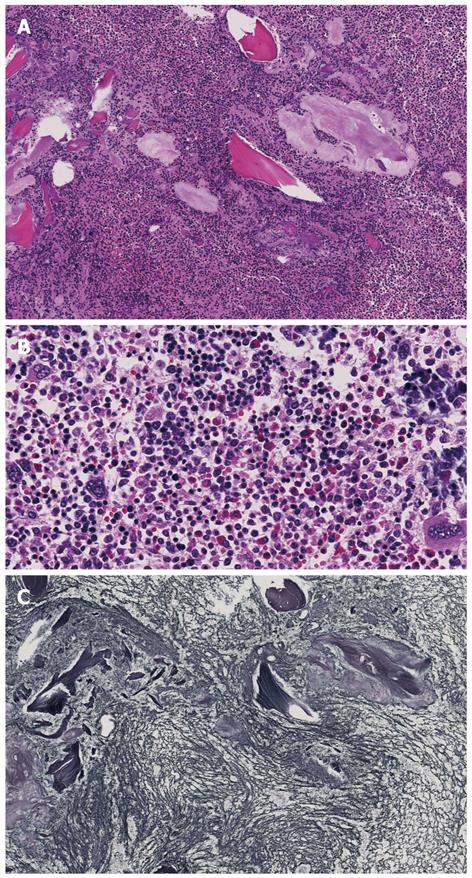

Bone marrow aspiration was attempted to evaluate the disease state but the tap was dry. Therefore, bone marrow biopsy was conducted from the ilium (Figure 2). Adipocytes were completely absent and hematopoietic cells markedly decreased. Thus, secondary myelofibrosis was diagnosed. There were no findings of progression to leukemia, and the patient was thus monitored by our hematology department.

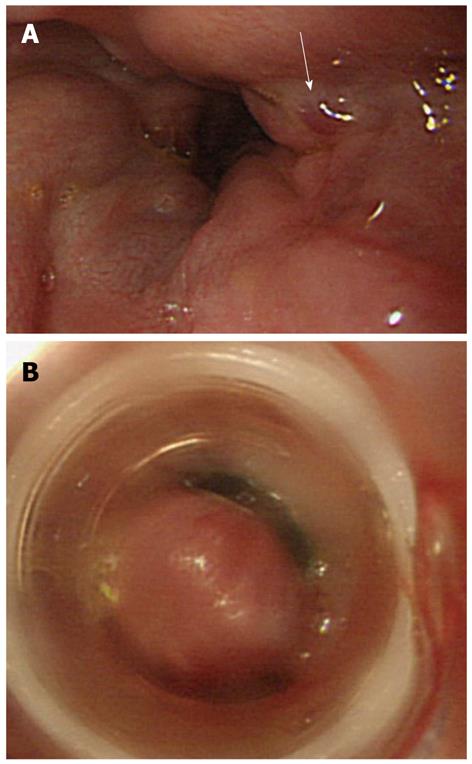

The patient was urgently transported to our center due to hematemesis in January 2011. Urgent endoscopy was conducted, and esophageal varices of Lm, F2, and Cb and the red color sign (hematocystic spot) in the lower esophagus were found (Figure 3). Therefore, endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) was conducted. A large quantity of poorly controlled ascites was observed, and the patient’s activities of daily living (ADL) were poor. Thus, no additional treatment such as endoscopic injection sclerotherapy was conducted, and the patient was discharged from the hospital. He had hematemesis in February of the same year, and bleeding was again stopped with EVL. However, no additional treatment was conducted for similar reasons. Furthermore, the patient had hematemesis again in March of the same year and was emergently transported to our center. Urgent endoscopy was conducted; however, because there was a large quantity of fresh blood in the stomach and esophagus, it was difficult to identify bleeding points. Blood pressure became unstable during the examination. Therefore, we abandoned EVL and inserted a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube. The patient was hospitalized at this time. However, the hemorrhagic shock was irreversible and he died 20 h after emergency transport. With informed consent from his family, autopsy was conducted the same day.

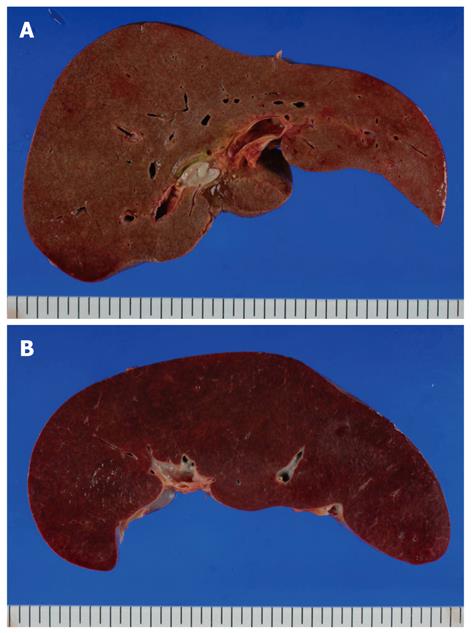

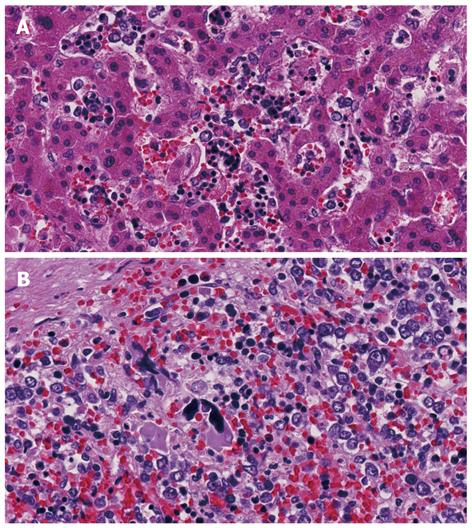

The enlarged liver weighed 1856 g but there were no obvious abnormalities on histopathological observation of the portal area or in hepatocytes. Extramedullary hemopoiesis was seen mainly in sinusoids. The spleen weighed 1572 g, indicating marked splenomegaly, and obscuration of white matter and the presence of bone marrow cells with splenic red pulp were the main features noted (Figures 4 and 5). In addition to these findings, small numbers of foci of extramedullary hematopoiesis were detected in the lungs, kidneys and lymph nodes around the pancreas. In bone marrow, adipocytes had completely disappeared, and 3-line cellular growth was seen. Severe fibrosis with mainly argyrophilic fibers was revealed by silver staining, and this finding was consistent with myelofibrosis (Figure 6).

Polycythemia vera is a myeloproliferative tumors resulting in absolute increases in the red blood cell count and circulating blood volume due to an acquired genetic abnormality of hematopoietic stem cells. Survival without treatment averages 18 mo, and the leading causes of death are reportedly thrombosis, progression to leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome or myelofibrosis, hemorrhage, and so on[3,4].

The present case was diagnosed as having polycythemia vera, and then showed a disease shift to secondary myelofibrosis approximately 30 years later. The histology of both biopsy and autopsy osseous samples showed increased cells in the 3-lineage differentiations. Since there was no morphological abnormality in them and limited proliferation of immature cells, it was considered that malignant lymphoma and leukemia could be ruled out.

Three years thereafter, the patient repeatedly suffered rupture of esophageal varices and ultimately died of this complication. Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension has various causes. Myeloproliferative tumors are often accompanied by marked splenomegaly and can cause portal hypertension due to increased portal vein flow[5,6]. Furthermore, Shaldon et al[7] reported that pre-sinusoidal blood flow resistance increases, in association with extramedullary hemopoiesis in hepatic sinusoids. Even if the increase in blood flow is mild, impaired blood flow can be regarded as the cause of increased pressure. Other than this, portal vein thrombosis within and outside of the liver and venous thrombosis can be causes in some cases. Liver histology in the present case showed mild fibrosis in the portal area and extramedullary hemopoiesis in hepatic sinusoids but no inflammatory cell infiltrate or reconstruction of hepatic lobules.

At autopsy, extramedullary hemopoiesis was not considered to be severe enough to have resulted in impaired blood flow. In addition, no obvious portal vein thrombosis or venous thrombosis was seen, while spleen weight was markedly increased as compared with that of the liver. These findings and splenic vein enlargement were consistent with portal hypertension. Thus, portal hypertension may have been caused by the increased blood flow associated with splenomegaly in our present case.

Myelofibrosis is often associated with splenomegaly, and we advocate paying close attention to myelofibrosis that may be accompanied by portal hypertension clinically. Patients with concomitant gastroesophageal varices can reportedly be treated effectively with splenectomy, splenic embolization, and transjugular intrahepatic portal-hepatic venous shunting[2,8].

The massive ascites in our present case was considered to have been caused by pre-sinusoidal lymphatic blockade due to extramedullary hemopoiesis; however, ascites was refractory to treatments such as the administration of diuretics. Therefore, we considered the possibility that transjugular intrahepatic portal-hepatic venous shunting would be effective.

The ADL of the present case were poor, and ascites was poorly controlled at the time of the initial hospitalization. Treatments for portal hypertension were thus considered to be too invasive and difficult; thus, they were not administered. When a patient is diagnosed as having myelofibrosis, screening endoscopy for esophageal and gastric varices should be conducted regularly, keeping in mind that portal hypertension may develop. When risk of rupture is considered, prophylactic endoscopic therapy or endovascular treatment should be considered while the patient’s general condition is good. However, the average survival period for myelofibrosis patients ranges from 3 to 7 years, and no more than 20% can expect a median survival of 10 years as this disease has a poor prognosis[2]. Therapy should be carefully selected in full consideration of invasiveness, as it impacts quality of life and prognosis.

| 1. | Ward HP, Block MH. The natural history of agnogenic myeloid metaplasia (AMM) and a critical evaluation of its relationship with the myeloproliferative syndrome. Medicine (. Baltimore). 1971;50:357-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 420] [Cited by in RCA: 398] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sullivan A, Rheinlander H, Weintraub LR. Esophageal varices in agnogenic myeloid metaplasia: disappearance after splenectomy. A case report. Gastroenterology. 1974;66:429-432. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Campbell PJ, Green AR. Management of polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2005;201-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Polycythemia vera: the natural history of 1213 patients followed for 20 years. Gruppo Italiano Studio Policitemia. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:656-664. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Oishi N, Swisher SN, Stormont JM, Schwartz SI. Portal hypertension in myeloid metaplasia. Report of a case without apparent portal obstruction. Arch Surg. 1960;81:80-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Blendis LM, Banks DC, Ramboer C, Williams R. Spleen blood flow and splanchnic haemodynamics in blood dyscrasia and other splenomegalies. Clin Sci. 1970;38:73-84. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Shaldon S, Sherlock S. Portal hypertension in the myeloproliferative syndrome and the reticuloses. Am J Med. 1962;32:758-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lukie BE, Card RT. Portal hypertension complicating myelofibrosis: reversal following splenectomy. Can Med Assoc J. 1977;117:771-772. [PubMed] |

Peer reviewer: Dr. Xiaoyun Liao, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Avenue, Room JF-208E, Boston, MA 02215, United States

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN