Published online Jul 14, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i26.3331

Revised: April 5, 2012

Accepted: April 12, 2012

Published online: July 14, 2012

The current financial turmoil in the United States has been attributed to multiple reasons including healthcare expenditure. Health care spending has increased from 5.7 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) in 1965 to 16 percent of the GDP in 2004. Healthcare is driven with a goal to provide best possible care available at that period of time. Guidelines are generally assumed to have the high level of certainty and security as conclusions generated by the conventional scientific method leading many clinicians to use guidelines as the final arbiters of care. To provide the standard of care, physicians follow guidelines, proposed by either groups of physicians or various medical societies or government organizations like National Comprehensive Cancer Network. This has lead to multiple tests for the patient and has not survived the test of time. This independence leads to lacunae in the standardization of guidelines, hence flooding of literature with multiple guidelines and confusion to patients and physicians and eventually overtreatment, inefficiency, and patient inconvenience. There is an urgent need to restrict articles with Guidelines and develop some strategy like have an intermediate stage of pre-guidelines and after 5-10 years of trials, a systematic launch of the Guidelines. There can be better ways than this for putting together guidelines as has been suggested by multiple authors and researchers.

- Citation: Vyas D, Vyas AK. Time to detoxify medical literature from guideline overdose. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(26): 3331-3335

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i26/3331.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i26.3331

A well researched guideline will reduce financial burden in United States healthcare. Increasing and excessive health care budget is affecting major industries in the United States. We know it is not the sole cause, but is one of the major reasons for the crisis. A jaw dropping fact is that health care spending has increased from 5.7 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) in 1965 to 16 percent of the GDP in 2004[1]. It has been estimated that in 2015, we will be spending close to 20 percent of the GDP, or an estimated $4 trillion, up from $1.9 trillion in 2004, on health care[2]. There is an obvious role of guidelines in reducing healthcare expenditure.

The initial step in systemic review was in 1970 with a perinatal trial[3]. Although guidelines are intended to assist physicians, this functionality seems frequently lost among the sea of guidelines that are available. Indeed, at any given point there are frequently multiple guidelines available with regard to a particular disease process, forcing physicians who wish to avoid accusations of undertreatment to order more than one diagnostic study or treatment (polypharmacy) referencing various guidelines. A well researched and tested guideline reduces healthcare cost and mismanaged malpractice lawsuits, and allows for better physician and patient understanding and better parameters for quality control in medical care. Most guidelines indicate that they are not a rule and should not be construed as establishing a legal standard of care.

Guidelines are generally assumed to have the high level of certainty and security as conclusions generated by the conventional scientific method leading many clinicians to use guidelines as the final arbiters of care[4] and sense of a shield to malpractice litigation. This has lead to multiple tests and it has not survived the test of the time. Fuchs suggested greater expenditures do not necessarily result in better health outcomes[5]. Guidelines may cause higher utilization of medical tests and procedures and, in some cases, have negative consequences for patients, as in the case of false-positive screening test results[6].

Another very compelling reason for its standardization is the use of guidelines in the malpractice lawsuit. Guidelines are frequently used as evidence by expert witness against a physician. It is very hard for judge and jury to understand the quality of evidence, but it easy for them to concur with evidence coming from an expert with a guidelines document.

Guidelines are used as a tool for quality measures. It seems immature to use consensus statements as performance measures or other similar tools to critique the quality of a physician’s care. It could be better addressed if it is derived from high-quality guidelines based on the highest level of evidence and derived in a more thoughtful manner. Protocols for quality must include guidelines, but it must have safety and patient care at its core with efficiency also as an outcome parameter. Any project without safety and efficiency is going to fail; hence we much have safecienct guidelines.

Guidelines are the basis of evidence based medicine (EBM). Guidelines are widely perceived as evidence based, not authority based, and therefore viewed as unbiased and valid. A systematic review uses preplanned scientific protocols and methods to summarize similar but separate studies to perform a scientific investigation for a specific question[7]. Druss et al[8] are of the opinion to rely more on guidelines due to increase in the quantity of relevant information. Evidence is a very strong word, but it’s important to understand how the facts are studied, and realize the biases of studies and researchers. A major responsibility of an educator is to be meticulous with the data collection and near perfect interpretation, but it can, at times, be challenging due to the size of data and variables involved. This is primarily due to an unprecedented explosion of medical knowledge in the past 50 years secondary to breakthroughs in numerous areas of medical science and information technology.

The Institute of Medicine stresses on use of guidelines for medical care to ensure high quality patient care[9]. Its needed as even the most sophisticated health care consumer has difficulty in deciding appropriate care for his or her condition[10,11]. Guidelines will assure the patient of adequate and appropriate treatment. Institute of Medicine stresses a need for a strong pertinent guideline for any particular disease. The providers and patients are faced not only with incongruous but also conflicting research findings.

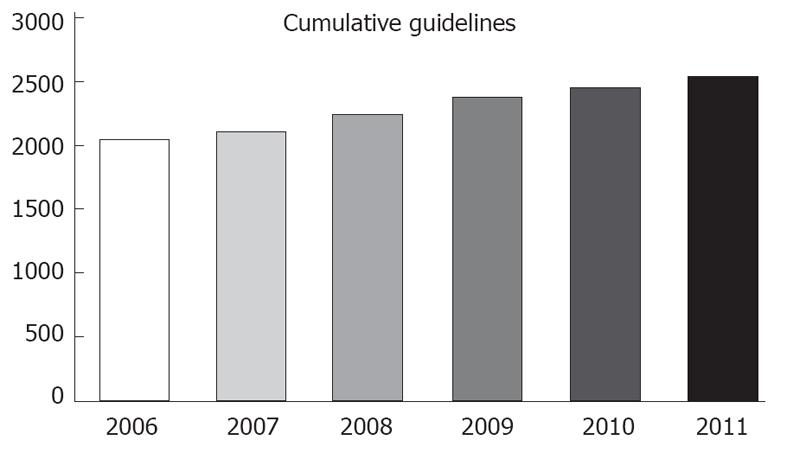

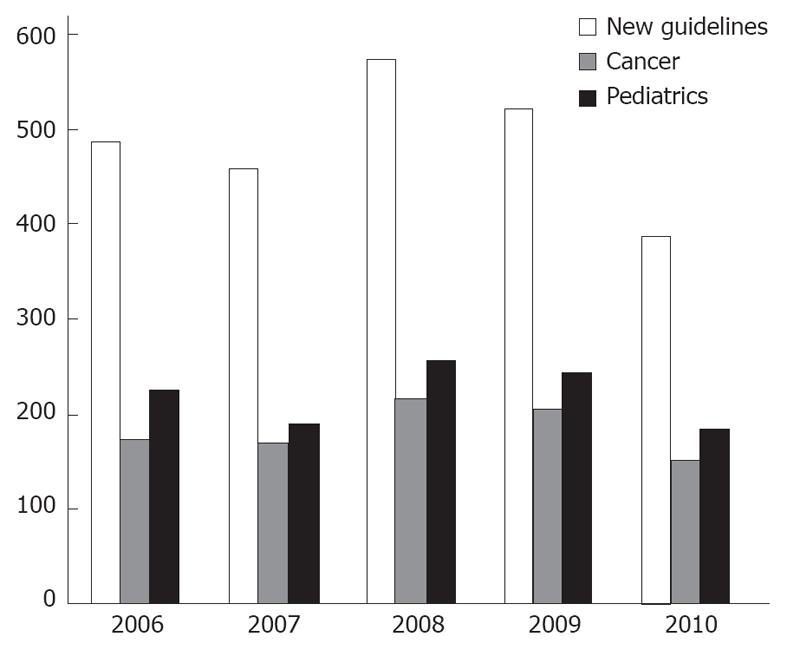

A major reason to stress their implementation is to reduce undesirable practice variation and reduce the use of services that are of minimal or questionable value. National Guidelines Clearinghouse (NGC, established in 1998) is a national body in the United States whose responsibility is to compile a bank of guidelines either by submission or active retrieval thru bodies like National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and American Heart Association (AHA). It has established its own submission standards and substandard guidelines are not incorporated. Even then there are at least 500 new guidelines submitted or reviewed every year (Figure 1). Similarly, National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) is established in the United Kingdom, with an objective to standardize the health care by issuing its own guidelines, after studying relevant literature and guidelines available at a given time in point. NICE uses term guidance in place of guidelines.

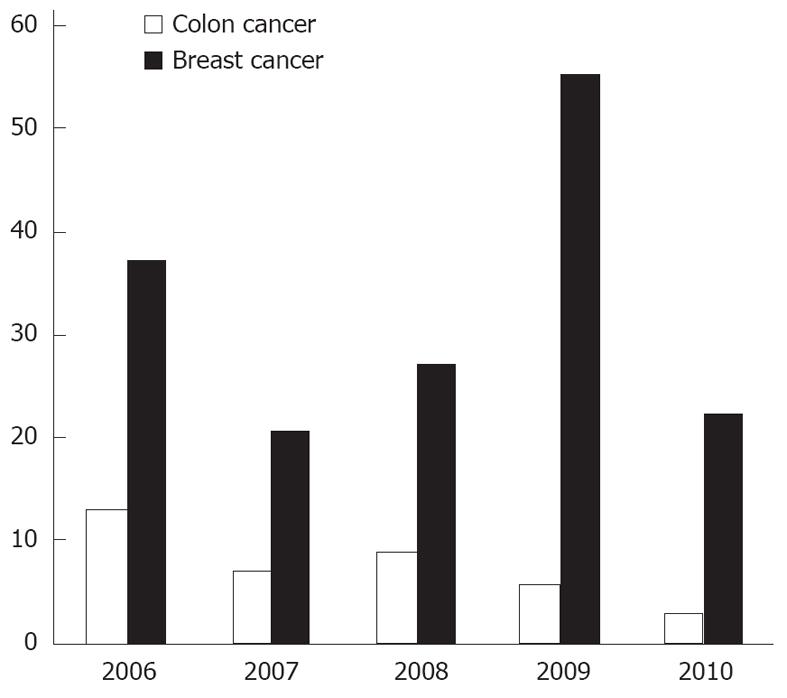

The term guideline has been drifting far from the original intent of the Institute of Medicine. Unfortunately a major share of current articles called “guidelines” is actually expert consensus reports[12]. There are interestingly too many guidelines, often on the same topic. For example, clinicians do not need 10 different adult pharyngitis guidelines[13]. Our information of total guidelines, compiled by NGC, shows there are close to 25% guidelines renewed every year and a disease as localized as breast has an average of more than 30 new guidelines every year for last 5 years (Figures 1, 2 and 3) (source: NGC). In 1999, after 1 year of NGC incorporation, there were total of 290 guidelines, with 82 cancers, 86 pediatrics and 21 and 7 breast and colon guidelines. The total number of guidelines, when this article is published has gone up to 2573 from 2060 in 2006 (source: NGC). This is according to the available information, the best compiled database of guidelines, by any organization internationally. According to their sources, it is possible a large number of guidelines are not even part of this pool.

Personal bias has been studied by multiple researchers. In Choudhary’s article, eighty-seven percent of authors had some form of interaction with the pharmaceutical industry with only seven percent admitting its influence on their inferences. Fifty-eight percent received financial support to perform research and fifty-five percent of respondents indicated that the guideline process had no formal process for declaring these relationships[14]. Unfortunately, all guideline committees begin with implicit biases and values affecting their worth[15]. A very relevant question arises: affect of sponsorship by organizations, personal biases, and absence of restriction by journals, organizations and publishing bodies in using term guideline.

Another reason for the shortcomings in the guidelines is the need for resources to conduct a rigorous systematic review. The resource crunch might push guideline developers to revert to short-cuts or processes centered on expert opinion[16]. On the contrary, a substantial investment in evidence gathering does not guarantee a sound guideline/evidence for a disease[17]. Guideline authors often rely on research that are non rigorous, and yield conflicting results[18]. This leads to pressure to rely more heavily on professional opinion which is problematic.

The exponential increase in guidelines is due to increasing number of research groups, societies, and associations performing analysis of a section of innumerable publications. It constitutes 40%-50% of indexed articles average annual volume. A large section of this growth is in articles on randomized trials and other types of clinical research used to guide evidence-based practice. Unfortunately, we are not seeing consistency in the guidelines issued on major areas of medicine. Contrast the guidelines with the decisions of any court of appeal in which some judgments are issued unanimously but most are not. Although unanimity is the rule in individual guidelines, it can be strikingly absent when different guidelines are compared.

It seems like we have come a full circle. The role of evidence-based practice, medical textbooks and editorials is to filter the literature filled with thousands of statements (based solely on the belief of the author or at best a consensus of experts)[19].

In an article on guidelines on management of pharyngitis, review of 4 North American and 6 European guidelines were included, and recommendations were found to go tangential to each other with regard to the use of a rapid antigen test and throat culture and the indication for antibiotics[13]. The reason for conflict is use of different data sets by different organizations. It has been suggested that guidelines are not necessary for every disease but are needed for diseases having significant practice variability and for which a valid evidence base can guide recommendations. They also suggested prioritizing individual recommendations[12].

A simple example is commonly used guidelines issued by cardiology organization, American College of Cardiology (ACC)/AHA guidelines. It is largely developed from lower levels of evidence or expert opinion[20]. It is flawed as it does not appear to follow the Institute of Medicine recommendations to separate the systematic review process from guideline formulation. According to the author, less than twenty percent of recommendations advocating a particular procedure or treatment in ACC/AHA practice guidelines are based on level A evidence. In another study of quality of recommendation, less than 45% recommendations in guidelines are based on high quality evidence[21]. These studies bring a very valid question to the rational of application of evidence based medicine, when evidence itself is weak.

Another example of rapid turnover and too early update is due to the pressure of incorporating the development in technology to clinical arena without due research is inclusion of immunohistochemistry results in a sentinel lymph node specimen in cancer. This was used in tumor node metastasis staging and was withdrawn after a short time. Situations like this make us wonder if we should make a pre-guideline of the results for a period of time and evaluate the data for its implication before incorporating the results for mass application. A similar example is withdrawal of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in menopausal females. HRT was initially thought (1995) to have more benefits and no absolute contraindications or major risks, but after its aggressive introduction and urgency for compliance, increased incidence of hormone related side effects like lethal breast cancer, ovarian cancer and stroke persuaded clinical bodies to withdraw the major recommendations of guidelines for HRT therapy. Another example is a simplistic tabulation of guidelines on mammography. There are five guidelines from the leading medical organizations in last two years with highly conflicting recommendations, except for almost identical recommendations from NCCN and American Cancer Society. Similarly, the guidelines for colonoscopy have huge conflicts, except the frequency of every 10 years. This has not been challenged for last 40 years, even though this is based on a very flimsy theory. Clinicians and researchers are still struggling to identify appropriate intervals for colonoscopy in low risk patients, although there is some progress in identifying patients needing early colonoscopy (Table 1).

| Yr | Age for first mammogram | Recommending authority | Frequency | Clinical breast exam |

| 2001 | 50-69 yr | Canadian Task Force | 1-2 yr | 1-3 yr |

| 2003 | 40-49 yr (1-2 yr) | ACOG | As in column 2 | Annually after 20 yr |

| > 50 yr (annually) | ||||

| 2007 | 40-49 yr (individualize) | ACP | As in column 2 | No statement |

| 50-74 yr (1-2 yr) | ||||

| 2009 | 40-49 yr (individualize) | USPSTF | 2 yr | Insufficient evidence |

| 50-74 yr (2 yr) | ||||

| 2010 | 40 yr and above | American Cancer Society | Annually | 20-40 yr every 3 yr and then annually |

| 2011 | NCCN | |||

| 2010 | 40 yr | NCI | 1-2 yr | No statement |

| 2011 | 47-73 yr | NHS, United Kingdom | 3 yr | No statement |

Differentiating effective and ineffective health resource utilization is an important health policy objective. There are multiple articles suggesting their opinion of the subject. This awkward situation can be partially resolved by training physicians in biostatistics, a necessary tool to interpret the findings of published clinical research[22]. At this point in time, the processes underlying guideline development is often vulnerable to bias and conflict of interest leading to sometimes poor quality. Grimshaw and group suggested a standardized and more diverse panel of physicians with competing interest with minimal bias[23]. Another group suggested two separate grading systems: (1) Quality of the evidence; and (2) Recommendations[24]. We don’t believe this will fix the state of affairs, but can definitely be one of the constructive steps. Another reason for streamlining the process is health quality measure reliance on guidelines. The NGC has thousands of guidelines produced by close to 300 organizations[25] underlining the need for urgent streamlining.

A more radical thought is to reject them unless there is evidence of appropriate changes in the guideline process. Physicians will make better clinical decisions based on valid primary data[12]. Another option is to update guideline after every 7-10 years or more if not much new data present and in areas of active research supplementing literature with pre-guidelines every 3-4 years. Also there can be a journal on guidelines where researchers can submit their opinion at the time of issues due date. And all the facts are incorporated and a final suggestion is given by the panel selected from the contributors and other established experts.

In summary, EBM is complex and incomplete. Guidelines must be directed only to the interests of patients and not to those who profit from them[4].

Peer reviewer: Dr. Benito Velayos, Department of Gastro-enterology, Hospital Clínico Valladolid, Ramón y Cajal 3, 47003 Valladolid, Spain

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Lubitz J. Health, technology, and medical care spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24 Suppl 2:W5R81-W5R85. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Borger C, Smith S, Truffer C, Keehan S, Sisko A, Poisal J, Clemens MK. Health spending projections through 2015: changes on the horizon. Health Aff (Millwood). 2006;25:w61-w73. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Chalmers I, Hetherington J, Newdick M, Mutch L, Grant A, Enkin M, Enkin E, Dickersin K. The Oxford Database of Perinatal Trials: developing a register of published reports of controlled trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:306-324. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Fuchs VR. More variation in use of care, more flat-of-the-curve medicine. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;Suppl Variation:VAR104-VAR107. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Haynes RB. Of studies, syntheses, synopses, summaries, and systems: the "5S" evolution of information services for evidence-based healthcare decisions. Evid Based Med. 2006;11:162-164. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Druss BG, Marcus SC. Growth and decentralization of the medical literature: implications for evidence-based medicine. J Med Libr Assoc. 2005;93:499-501. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Institute of Medicine. Knowing What Works in Health Care: A Roadmap for the Nation. Washington, DC: National Academies Press 2008; . |

| 10. | Berwick DM, James B, Coye MJ. Connections between quality measurement and improvement. Med Care. 2003;41:I30-I38. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Wennberg JE, Fisher ES. Finding high quality, efficient providers for value purchasing: cohort methods better than methods based on events. Med Care. 2002;40:853-855. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Shaneyfelt TM, Centor RM. Reassessment of clinical practice guidelines: go gently into that good night. JAMA. 2009;301:868-869. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Matthys J, De Meyere M, van Driel ML, De Sutter A. Differences among international pharyngitis guidelines: not just academic. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:436-443. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Choudhry NK, Stelfox HT, Detsky AS. Relationships between authors of clinical practice guidelines and the pharmaceutical industry. JAMA. 2002;287:612-617. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Detsky AS. Sources of bias for authors of clinical practice guidelines. CMAJ. 2006;175:1033, 1035. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Browman G, Gómez de la Cámara A, Haynes B, Jadad A, Gabriel R. [Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines development. From the bottom, to the top]. Med Clin (Barc). 2001;116:267-270. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Ricci S, Celani MG, Righetti E. Development of clinical guidelines: methodological and practical issues. Neurol Sci. 2006;27 Suppl 3:S228-S230. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Cook D, Giacomini M. The trials and tribulations of clinical practice guidelines. JAMA. 1999;281:1950-1951. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Eddy DM. Evidence-based medicine: a unified approach. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24:9-17. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Tricoci P, Allen JM, Kramer JM, Califf RM, Smith SC. Scientific evidence underlying the ACC/AHA clinical practice guidelines. JAMA. 2009;301:831-841. [PubMed] |

| 21. | McAlister FA, van Diepen S, Padwal RS, Johnson JA, Majumdar SR. How evidence-based are the recommendations in evidence-based guidelines? PLoS Med. 2007;4:e250. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Boonyasai RT, Windish DM, Chakraborti C, Feldman LS, Rubin HR, Bass EB. Effectiveness of teaching quality improvement to clinicians: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;298:1023-1037. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Grimshaw JM, Russell IT. Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice: a systematic review of rigorous evaluations. Lancet. 1993;342:1317-1322. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Guyatt G, Vist G, Falck-Ytter Y, Kunz R, Magrini N, Schunemann H. An emerging consensus on grading recommendations? ACP J Club. 2006;144:A8-A9. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Available from: http: //wwwguidelinegov. |