Published online Jul 7, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i25.3201

Revised: March 2, 2012

Accepted: March 9, 2012

Published online: July 7, 2012

Gastric stump carcinoma (GSC) following remote gastric surgery is widely recognized as a separate entity within the group of various types of gastric cancer. Gastrectomy is a well established risk factor for the development of GSC at a long time after the initial surgery. Both exo- as well as endogenous factors appear to be involved in the etiopathogenesis of GSC, such as achlorhydria, hypergastrinemia and biliary reflux, Epstein-Barr virus and Helicobacter pylori infection, atrophic gastritis, and also some polymorphisms in interleukin-1β and maybe cyclo-oxygenase-2. This review summarizes the literature of GSC, with special reference to reliable early diagnostics. In particular, dysplasia can be considered as a dependable morphological marker. Therefore, close endoscopic surveillance with multiple biopsies of the gastroenterostomy is recommended. Screening starting at 15 years after the initial ulcer surgery can detect tumors at a curable stage. This approach can be of special interest in Eastern European countries, where surgery for benign gastroduodenal ulcers has remained a practice for a much longer time than in Western Europe, and therefore GSC is found with higher frequency.

- Citation: Sitarz R, Maciejewski R, Polkowski WP, Offerhaus GJA. Gastroenterostoma after Billroth antrectomy as a premalignant condition. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(25): 3201-3206

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i25/3201.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i25.3201

The first partial gastrectomy with gastroduodenostomy was performed by Billroth in 1881 and was followed by the first gastrojejunostomy 3 years later. Both procedures became known as Billroth I and II, respectively[1]. Although the famous Viennese surgeon Theodor Billroth is credited for the first gastric resection, known as the Billroth I procedure, the less well-known Ludwik Rydygier from Poland, performed and described the procedure several months earlier[2]. Particularly in Europe, the Billroth II resection became the most popular treatment for peptic ulcer disease until the mid 1970s[3]. Since then, a significant decrease of peptic ulcer surgery was seen due to the introduction of H2-receptor antagonists[4], and later the proton pump inhibitors[5]. In the early 1980s, the discovery of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)[6] as the main cause of peptic ulcer disease further diminished the role of surgery in the treatment of this disease[7-12]. Surgical treatment for uncomplicated peptic ulcer disease became rare, but operations for complications of peptic ulcer disease such as perforation, bleeding or gastric outlet obstruction are still regularly performed. The rise of the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs explains part of this occurrence[13-16]. In Eastern Europe, the prevalence of surgery for benign gastroduodenal ulcers remained higher for a longer time than in Western Europe. In Poland for example, several thousand complicated as well as chronic peptic ulcer patients were still operated upon[17-20], and there, the introduction of of antisecretory drugs occurred in the late 1980s[21]. Nevertheless, complications of peptic ulcer surgery will presumably become less important there as a public health problem[22].

Billroth antrectomy and its various modifications remove the part where the ulcer is located and that contains the gastrin-producing antral mucosa responsible for the stimulation of acid production through the oxyntic mucosa. It also induces biliary reflux, felt to be beneficial for healing due to its alkaline contents. The majority of patients with peptic ulcer disease will have an antrum-predominant H. pylori gastritis[23,24], The biliary reflux creates a microenvironment that is not suitable for H. pylori and it will eradicate the microorganisms from the anastomosis after surgery. The microscopy of the anastomosis will therefore change from the chronic active H. pylori gastritis picture into that of the typical reflux gastritis. The most important features of reflux gastritis are foveolar hyperplasia, congestion, paucity of inflammatory infiltrate, reactive epithelial change and smooth muscle fiber proliferation. These changes are already apparent shortly after surgery; less so when a Roux-en-Y conversion is carried out to avoid reflux[25,26]. The picture is therefore directly related to the reflux of bile, as is the eradication of H. pylori from the anastomosis.

In the long run, other microscopic features are encountered in the operated stomach[27]. Loss of parietal cells with the subsequent disappearance of the chief cells introduces an accelerated mucosal atrophy that is caused by the lack of the trophic hormone gastrin and the vagotomy that is mostly done simultaneously. The specialized glandular mucosa is replaced by intestinal metaplasia and pseudopyloric metaplasia[28-31]. Atrophy of the gastric mucosa may lead to vitamin B12 deficiency. At the site of the anastomosis, the glands often become cystically dilated, and sometimes these cystically dilated glands herniate through the muscularis mucosae. This provides a nodular aspect to the anastomosis and gives rise to a microscopic picture known as gastritis polyposis cystica or gastritis cystica profunda[32-34]. Erosions may occur as a result of compromised vasculature due to the surgery, but in the case of persistent ulceration after surgery, Zollinger-Ellison-like syndrome or a retained antrum needs consideration and these conditions are accompanied by high gastrin levels. The retained antrum is caused by resection that is too limited and G-cell hyperplasia in the stretch of antral mucosa left behind[35,36].

Xanthelasmas, also known as gastric xanthomas or gastric lipid islands, are aggregates of foamy macrophages filled with lipids that can be seen in the stomach and more often after partial gastrectomy[37,38]. At endoscopy, they appear as grossly visible whitish nodules or plaques, well circumscribed, with a size varying from 1 to 10 mm in diameter[39,40]. They typically occur along the lesser curve[41], the so-called “magenstrasse” where generally reflux is most severe. It is felt that these aggregates phagocytose remnants of cellular debris after degradation due to chemical injury, and they are harmless. Their importance lies in the fact that these should not be confused with signet ring cell carcinoma, because the microscopy of xanthelasma can resemble signet ring cells. Special stains for mucin or immunohistochemistry for cytokeratins versus histiocytic macrophages makes this differentiation easy[42,43]. Xanthelasmas occur more frequently in stomachs harboring other pathological changes such as chronic gastritis, atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia[39,44]. The significance of these lesions remains unknown.

The stump of the stomach after remote gastric resection because of benign ulcer disease is a well-defined premalignant condition. Many studies in the past have confirmed that, after remote partial gastrectomy, there is an increased risk for stomach cancer[3,45-49]. GSC is defined as a malignancy of the stomach occurring > 5 years after initial partial gastrectomy, to confusion with cancer recurrence after initial misdiagnosis. The risk for stump cancer is remarkable because most of these patients suffer from peptic ulcer disease prior to surgery. The relation between peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer is not fully understood. Gastric cancer and peptic ulcer disease are inversely associated and they are accompanied by distinct patterns of acid secretion[50]; by contrast, gastric ulcers, non-peptic gastric ulcers, and gastric cancer partly share pathophysiological features[51-53]. The part of the stomach that is at the highest risk for gastric cancer is removed by surgery. Nevertheless, with an increasing postoperative interval, there is a steadily increasing risk for stomach cancer in the gastric remnant. After more than 15-20 years postoperatively, the risk is higher than can be expected for an age- and sex-matched general population, and it rapidly increases thereafter[45,48,54]. In line with the increased risk for stomach cancer, the post-gastrectomy stomach also harbors dysplasia relatively frequently[29,55,56]. The dysplasia is typically encountered around the gastric anastomosis, and similarly the cancers are almost exclusively found there. Both the dysplasia and the cancers can be multifocal and extensive mapping of the mucosa with endoscopic biopsies is warranted. Unlike primary gastric cancer, which is frequently resectable (resectability rate in Poland: 66%), gastric stump carcinoma once detected because of symptoms is virtually unresectable in the majority of patients In view of the increased risk, surveillance of post-gastrectomy patients has been advocated and it can indeed detect cancer at an early and operable stage[57]. Whether or not large-scale screening would be indicated is however questionable. In a screening program carried out in Amsterdam among > 500 patients > 15 years postoperatively, 10 cancers were found; six of which turned out to be early cancers[56]. Mortality of stomach cancer among these screened individuals was, however, only marginally different from that among the patients who did not participate in the screening program, after an observation period of 10 years. Moreover, a similar difference in mortality was observed in lung cancer, suggestive of selection bias among the screened patients[58].

It is thought that after partial gastrectomy, an environment is created that is favorable for the development of cancer. Patients enter an accelerated neoplastic process due to the altered microenvironment. The stump carcinomas evolve as the end result of a series of mutagenic cell transformations, leading to stepwise tumor progression from atrophic gastritis with metaplasia via dysplasia to invasive carcinoma. During tumor progression an increased proliferation and expansion of the proliferative compartment towards the luminal surface is observed. This is accompanied by an increasing concomitant chance of mutations, because the proliferating cells are particularly vulnerable to mutation. Biliary reflux, achlorhydria, atrophic gastritis and formation of N-nitroso compounds are considered factors that contribute to carcinogenesis in the gastric stump[3,59,60]. It has been shown that the changes in the quantity of the nitrate-reducing bacteria and in the N-nitrosamine concentration depend on the type of surgical intervention performed. The highest content of nitrate-reducing bacteria and the N-nitrosamine concentration were found in the gastric juice of patients after Billroth II antrectomy, and the lowest values after highly selective vagotomy[61].

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) positivity by RNA in situ hybridization is seen more often in carcinomas in the gastric remnant than in the intact stomach[62]. In contrast, H. pylori is less frequently observed[63]. Interestingly, there is an inverse relationship between positivity for EBV and positive immunohistochemistry for TP53; also loss of heterozygosity of 17p at the locus of TP53 is less frequently observed in EBV-positive stump carcinomas[64]. It has been reported that the EBV-encoded EBNA-5 protein can form a complex with TP53 and retinoblastoma proteins, and it is conceivable that this may lead to accelerated degradation of either one of these proteins[65].

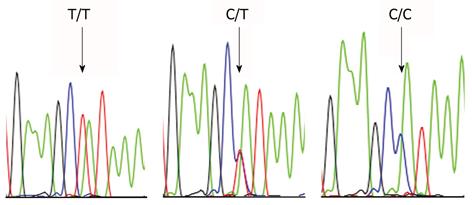

Endogenous factors may also play a role. The interleukin (IL)-1β 31T>C polymorphism is associated with higher gastric cancer risk. This allele confers hypoacidity to the oxyntic mucosa of the H. pylori-infected intact stomach and it thereby induces a corpus-predominant inflammatory gastritis[66,67]. The IL-1β-31T>C polymorphism is also associated with GSC (Table 1 and Figure 1)[68]. Apparently, the relatively few peptic ulcer disease patients carrying this genotype are at particularly high risk for the development of stomach cancer, after operation. Surgery has a similar effect as pharmacologically induced acid suppression; a fact that is known to lead from an antrum- to a corpus-predominant inflammatory picture in the gastric mucosa.

| Genotype of IL-1β-31T>C1 | Gastric stumpcancer | Conventional gastriccancer |

| CC | 8/30 (27) | 21/96 (22) |

| TC | 19/30 (63) | 36/96 (37) |

| TT | 3/30 (10) | 39/96 (41) |

| Presence of C allele | 90 | 59 |

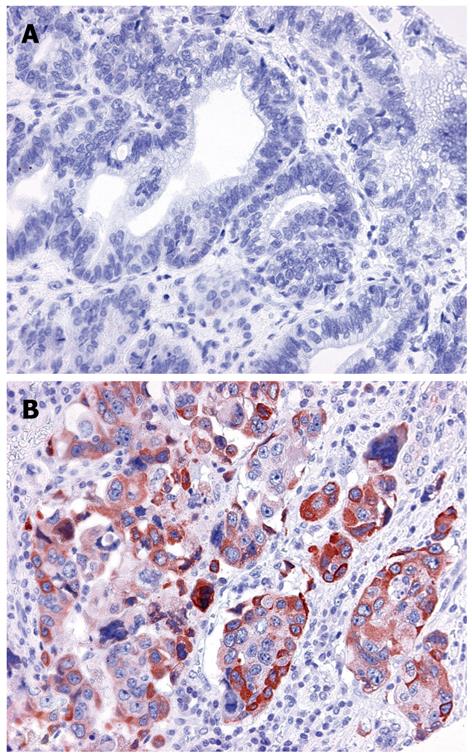

Cyclo-oxygenase (COX)-2 expression is increased in gastric stump cancer and the 765 G allele of COX-2 is associated with higher gastric cancer risk (Table 2 and Figure 2)[69]. There is however no direct relationship between expression of COX-2 and the -765 C>G polymorphism in gastric stump cancer. This finding contrasts with observations in the duodenum of familial adenomatous polyposis patients, in whom this polymorphism is associated with increased COX-2 expression in the normal mucosa[70].

| COX-2 -765 genotype1 | Gastric stump cancer | Conventional gastric cancer | Early-onset gastric cancer | Controls |

| GG | 23/30 (77) | 73/96 (76) | 80/115 (70) | 59 (59) |

| GC | 5/30 (17) | 19/96 (20) | 33/115 (29) | 32 (32) |

| CC | 2/30 (7) | 4/96 (4) | 2/115 (2) | 9 (9) |

| Presence of C allele | 23 | 24 | 30 | 41 |

Partial gastrectomy for benign peptic ulcer disease is a well-established premalignant condition. With increasing postoperative interval since the initial surgery, the risk steadily increases and after more than 15-20 years postoperatively, gastric cancer risk is higher than that of age and sex-matched controls with intact stomachs. The surgery itself and the resulting biliary reflux seem responsible for the risk. Endogenous factors such as polymorphisms in IL-1β and COX-2 may contribute. EBV infection is more prevalent than in the intact stomach, and H. pylori infection less frequent. EBV may interact with the TP53 gene. Stump cancer is preceded by well-defined preinvasive precursor lesions, most notably dysplasia. Dysplasia can be considered a dependable morphological marker, amenable for early detection by endoscopic surveillance.

| 1. | Busman DC. Theodor Billroth 1829 - 1894. Acta Chir Belg. 2006;106:743-752. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Sablinski T, Tilney NL. Ludwik Rydygier and the first gastrectomy for peptic ulcer. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1991;172:493-496. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Safatle-Ribeiro AV, Ribeiro U, Reynolds JC. Gastric stump cancer: what is the risk? Dig Dis. 1998;16:159-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Feldman M, Burton ME. Histamine2-receptor antagonists. Standard therapy for acid-peptic diseases (2). N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1749-1755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Modlin IM. From Prout to the proton pump--a history of the science of gastric acid secretion and the surgery of peptic ulcer. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;170:81-96. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;1:1311-1315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3302] [Cited by in RCA: 3313] [Article Influence: 78.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Schwesinger WH, Page CP, Sirinek KR, Gaskill HV, Melnick G, Strodel WE. Operations for peptic ulcer disease: paradigm lost. J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5:438-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ishikawa M, Ogata S, Harada M, Sakakihara Y. Changes in surgical strategies for peptic ulcers before and after the introduction of H2-receptor antagonists and endoscopic hemostasis. Surg Today. 1995;25:318-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Walker LG. Trends in the surgical management of duodenal ulcer. A fifteen year study. Am J Surg. 1988;155:436-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wyllie JH, Clark CG, Alexander-Williams J, Bell PR, Kennedy TL, Kirk RM, MacKay C. Effect of cimetidine on surgery for duodenal ulcer. Lancet. 1981;1:1307-1308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bloom BS, Kroch E. Time trends in peptic ulcer disease and in gastritis and duodenitis. Mortality, utilization, and disability in the United States. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1993;17:333-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kleeff J, Friess H, Büchler MW. How Helicobacter Pylori changed the life of surgeons. Dig Surg. 2003;20:93-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Harbison SP, Dempsey DT. Peptic ulcer disease. Curr Probl Surg. 2005;42:346-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sánchez-Bueno F, Marín P, Ríos A, Aguayo JL, Robles R, Piñero A, Fernández JA, Parrilla P. Has the incidence of perforated peptic ulcer decreased over the last decade? Dig Surg. 2001;18:444-447; discussion 447-448;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Henriksson AE, Edman AC, Nilsson I, Bergqvist D, Wadström T. Helicobacter pylori and the relation to other risk factors in patients with acute bleeding peptic ulcer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:1030-1033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gisbert JP, Gonzalez L, de Pedro A, Valbuena M, Prieto B, Llorca I, Briz R, Khorrami S, Garcia-Gravalos R, Pajares JM. Helicobacter pylori and bleeding duodenal ulcer: prevalence of the infection and role of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:717-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sołtysiak A, Kaszyński M. 20-year experience in highly selective vagotomies with or without pyloroplasty in patients with complicated and uncomplicated duodenal ulcers. Pol Przegl Chir. 1995;67:564-573. |

| 18. | Wysocki A, Beben P. [Type of surgery and mortality rate in perforated duodenal ulcer]. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2001;11:148-150. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Janik J, Chwirot P. Perforated peptic ulcer--time trends and patterns over 20 years. Med Sci Monit. 2000;6:369-372. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Kleba T. [Early and late complications after surgical gastric resection for peptic ulcer]. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 1997;2:313-314. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Janik J, Chwirot P. Peptic ulcer disease before and after introduction of new drugs--a comparison from surgeon's point of view. Med Sci Monit. 2000;6:365-368. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Sinning C, Schaefer N, Standop J, Hirner A, Wolff M. Gastric stump carcinoma - epidemiology and current concepts in pathogenesis and treatment. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33:133-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Sipponen P, Seppälä K, Aärynen M, Helske T, Kettunen P. Chronic gastritis and gastroduodenal ulcer: a case control study on risk of coexisting duodenal or gastric ulcer in patients with gastritis. Gut. 1989;30:922-929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | El-Zimaity HMT O, Kim JG, Akamatsu T, Gürer IE, Simjee AE, Graham DY. Geographic differences in the distribution of intestinal metaplasia in duodenal ulcer patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:666-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fukuhara K, Osugi H, Takada N, Takemura M, Higashino M, Kinoshita H. Reconstructive procedure after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer that best prevents duodenogastroesophageal reflux. World J Surg. 2002;26:1452-1457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Shinoto K, Ochiai T, Suzuki T, Okazumi S, Ozaki M. Effectiveness of Roux-en-Y reconstruction after distal gastrectomy based on an assessment of biliary kinetics. Surg Today. 2003;33:169-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Offerhaus GJ. Gastric stump cancer: lessons from old specimens. Lancet. 1994;343:66-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Savage A, Jones S. Histological appearances of the gastric mucosa 15--27 years after partial gastrectomy. J Clin Pathol. 1979;32:179-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Offerhaus GJ, van de Stadt J, Huibregtse K, Tersmette AC, Tytgat GN. The mucosa of the gastric remnant harboring malignancy. Histologic findings in the biopsy specimens of 504 asymptomatic patients 15 to 46 years after partial gastrectomy with emphasis on nonmalignant lesions. Cancer. 1989;64:698-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Geboes K, Rutgeerts P, Broeckaert L, Vantrappen G, Desmet V. Histologic appearances of endoscopic gastric mucosal biopsies 10--20 years after partial gastrectomy. Ann Surg. 1980;192:179-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Farrands PA, Blake JR, Ansell ID, Cotton RE, Hardcastle JD. Endoscopic review of patients who have had gastric surgery. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;286:755-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Littler ER, Gleibermann E. Gastritis cystica polyposa. (Gastric mucosal prolapse at gastroenterostomy site, with cystic and infiltrative epithelial hyperplasia). Cancer. 1972;29:205-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Wu MT, Pan HB, Lai PH, Chang JM, Tsai SH, Wu CW. CT of gastritis cystica polyposa. Abdom Imaging. 1994;19:8-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Franzin G, Novelli P. Gastritis cystica profunda. Histopathology. 1981;5:535-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lundell L, Lindstedt G, Olbe L. Origin of gastrin liberated by gastrin releasing peptide in man. Gut. 1987;28:1128-1133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | De Graef J, Keuppens F, Willems G, Woussen-Colle MC. [Antral G cell hyperplasia in the genesis of peptic ulcer]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1979;3:3-6. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Domellöf L, Eriksson S, Helander HF, Janunger KG. Lipid islands in the gastric mucosa after resection for benign ulcer disease. Gastroenterology. 1977;72:14-18. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Terruzzi V, Minoli G, Butti GC, Rossini A. Gastric lipid islands in the gastric stump and in non-operated stomach. Endoscopy. 1980;12:58-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Oviedo J, Swan N, Farraye FA. Gastric xanthomas. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3216-3218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Khachaturian T, Dinning JP, Earnest DL. Gastric xanthelasma in a patient after partial gastrectomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1588-1589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Chen YS, Lin JB, Dai KS, Deng BX, Xu LZ, Lin CD, Jiang ZG. Gastric xanthelasma. Chin Med J (Engl). 1989;102:639-643. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Kimura K, Hiramoto T, Buncher CR. Gastric xanthelasma. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:110-117. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Ludvíková M, Michal M, Datková D. Gastric xanthelasma associated with diffuse signet ring carcinoma. A potential diagnostic problem. Histopathology. 1994;25:581-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Gencosmanoglu R, Sen-Oran E, Kurtkaya-Yapicier O, Tozun N. Xanthelasmas of the upper gastrointestinal tract. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:215-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Toftgaard C. Gastric cancer after peptic ulcer surgery. A historic prospective cohort investigation. Ann Surg. 1989;210:159-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Lundegårdh G, Adami HO, Helmick C, Zack M, Meirik O. Stomach cancer after partial gastrectomy for benign ulcer disease. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:195-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Fisher SG, Davis F, Nelson R, Weber L, Goldberg J, Haenszel W. A cohort study of stomach cancer risk in men after gastric surgery for benign disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:1303-1310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Offerhaus GJ, Tersmette AC, Huibregtse K, van de Stadt J, Tersmette KW, Stijnen T, Hoedemaeker PJ, Vandenbroucke JP, Tytgat GN. Mortality caused by stomach cancer after remote partial gastrectomy for benign conditions: 40 years of follow up of an Amsterdam cohort of 2633 postgastrectomy patients. Gut. 1988;29:1588-1590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Nicholls JC. Stump cancer following gastric surgery. World J Surg. 1979;3:731-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | El-Omar EM, Oien K, El-Nujumi A, Gillen D, Wirz A, Dahill S, Williams C, Ardill JE, McColl KE. Helicobacter pylori infection and chronic gastric acid hyposecretion. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:15-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 411] [Cited by in RCA: 401] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 51. | Molloy RM, Sonnenberg A. Relation between gastric cancer and previous peptic ulcer disease. Gut. 1997;40:247-252. [PubMed] |

| 52. | Hansson LE, Nyrén O, Hsing AW, Bergström R, Josefsson S, Chow WH, Fraumeni JF, Adami HO. The risk of stomach cancer in patients with gastric or duodenal ulcer disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:242-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 432] [Cited by in RCA: 431] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Bahmanyar S, Ye W, Dickman PW, Nyrén O. Long-term risk of gastric cancer by subsite in operated and unoperated patients hospitalized for peptic ulcer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1185-1191. [PubMed] |

| 54. | Tersmette AC, Goodman SN, Offerhaus GJ, Tersmette KW, Giardiello FM, Vandenbroucke JP, Tytgat GN. Multivariate analysis of the risk of stomach cancer after ulcer surgery in an Amsterdam cohort of postgastrectomy patients. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:14-21. [PubMed] |

| 55. | Saukkonen M, Sipponen P, Kekki M. The morphology and dynamics of the gastric mucosa after partial gastrectomy. Ann Clin Res. 1981;13:156-158. [PubMed] |

| 56. | Offerhaus GJ, Stadt J, Huibregtse K, Tytgat G. Endoscopic screening for malignancy in the gastric remnant: the clinical significance of dysplasia in gastric mucosa. J Clin Pathol. 1984;37:748-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Tytgat GN, Offerhaus JG, vd Stadt J, Huibregtse K. Early gastric stump cancer: macroscopic and microscopic appearance. Hepatogastroenterology. 1989;36:103-108. [PubMed] |

| 58. | Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, Libby DM, Pasmantier MW, Smith JP, Miettinen OS. Survival of patients with stage I lung cancer detected on CT screening. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1763-1771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1163] [Cited by in RCA: 1183] [Article Influence: 59.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Kondo K. Duodenogastric reflux and gastric stump carcinoma. Gastric Cancer. 2002;5:16-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Watt PC, Sloan JM, Donaldson JD, Patterson CC, Kennedy TL. Relationship between histology and gastric juice pH and nitrite in the stomach after operation for duodenal ulcer. Gut. 1984;25:246-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Kopański Z, Brandys J, Piekoszewski W, Schlegel-Zawadzka M, Witkowska B. The bacterial flora and the changes of the N-nitrosamine concentration in the operated stomach. Przegl Lek. 2001;58:348-350. [PubMed] |

| 62. | Yamamoto N, Tokunaga M, Uemura Y, Tanaka S, Shirahama H, Nakamura T, Land CE, Sato E. Epstein-Barr virus and gastric remnant cancer. Cancer. 1994;74:805-809. [PubMed] |

| 63. | Baas IO, van Rees BP, Musler A, Craanen ME, Tytgat GN, van den Berg FM, Offerhaus GJ. Helicobacter pylori and Epstein-Barr virus infection and the p53 tumour suppressor pathway in gastric stump cancer compared with carcinoma in the non-operated stomach. J Clin Pathol. 1998;51:662-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | van Rees BP, Caspers E, zur Hausen A, van den Brule A, Drillenburg P, Weterman MA, Offerhaus GJ. Different pattern of allelic loss in Epstein-Barr virus-positive gastric cancer with emphasis on the p53 tumor suppressor pathway. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1207-1213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Szekely L, Selivanova G, Magnusson KP, Klein G, Wiman KG. EBNA-5, an Epstein-Barr virus-encoded nuclear antigen, binds to the retinoblastoma and p53 proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5455-5459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | El-Omar EM, Carrington M, Chow WH, McColl KE, Bream JH, Young HA, Herrera J, Lissowska J, Yuan CC, Rothman N. Interleukin-1 polymorphisms associated with increased risk of gastric cancer. Nature. 2000;404:398-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1690] [Cited by in RCA: 1689] [Article Influence: 65.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 67. | El-Omar EM, Carrington M, Chow WH, McColl KE, Bream JH, Young HA, Herrera J, Lissowska J, Yuan CC, Rothman N. The role of interleukin-1 polymorphisms in the pathogenesis of gastric cancer. Nature. 2001;412:99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Sitarz R, de Leng WW, Polak M, Morsink FH, Bakker O, Polkowski WP, Maciejewski R, Offerhaus GJ, Milne AN. IL-1B -31T>C promoter polymorphism is associated with gastric stump cancer but not with early onset or conventional gastric cancers. Virchows Arch. 2008;453:249-255. [PubMed] |

| 69. | Sitarz R, Leguit RJ, de Leng WW, Polak M, Morsink FM, Bakker O, Maciejewski R, Offerhaus GJ, Milne AN. The COX-2 promoter polymorphism -765 G>C is associated with early-onset, conventional and stump gastric cancers. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:685-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Brosens LA, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Keller JJ, Hustinx SR, Carvalho R, Morsink FH, Hylind LM, Offerhaus GJ, Giardiello FM, Goggins M. Increased cyclooxygenase-2 expression in duodenal compared with colonic tissues in familial adenomatous polyposis and relationship to the -765G ->C COX-2 polymorphism. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4090-4096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Peer reviewer: Antonio Basoli, Professor, General Surgery “Paride Stefanini”, Università di Roma-Sapienza, Viale del Policlinico 155, 00161 Roma, Italy

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Zhang DN